History of the Cape Colony from 1806 to 1870 facts for kids

The history of the Cape Colony from 1806 to 1870 tells the story of the Cape Colony in South Africa during a time of conflict. This period saw the Cape Frontier Wars, which were battles between European settlers and the native Xhosa people. The Xhosa fought to protect their land from European rule.

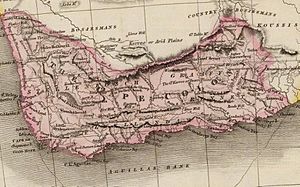

The Cape Colony was the first European settlement in South Africa. It was first controlled by the Dutch, but the British later took it over. After more fighting, British forces captured the Cape in January 1806. The Dutch surrendered to Sir David Baird. In 1814, the Netherlands officially gave the colony to the British. At this time, the colony covered about 194,000 square kilometers. It had around 60,000 people. This included 27,000 white settlers, 17,000 free Khoikhoi people, and many enslaved people. These enslaved people were mostly brought from other parts of Africa and Malaysia.

Contents

- Early Conflicts: Xhosa Wars Begin

- British Settlers Arrive in 1820

- Dutch Disagreements with British Rule

- Third Cape Frontier War (1834–1836)

- The Great Trek (1836–1840)

- War of the Axe (1846)

- British Power Expands (1847)

- Convict Protests and a New Government (1848–1853)

- Eighth Frontier War (1850–1853)

- Xhosa Cattle-Killing and Famine (1854–1858)

- Sir George Grey's Time as Governor (1854–1870)

Early Conflicts: Xhosa Wars Begin

The Cape Colony had already seen some wars with the Xhosa people before it became British. The Xhosa who crossed the border were moved from an area called the Zuurveld. This land, between the Sundays River and Great Fish River, became a neutral zone.

For some time, the Xhosa took over this neutral land and attacked the colonists. In December 1811, Colonel John Graham led an army to remove them. The Xhosa were forced to move back beyond the Fish River. A town named Graham's Town, later Grahamstown, was built where Colonel Graham's headquarters had been.

In 1819, more trouble started between the Cape Colony government and the Xhosa. The government wanted some stolen cattle returned. On April 22, 1819, a Xhosa prophet-chief named Makana led an attack on Graham's Town. It was defended by a small number of British troops. When more soldiers arrived, the Xhosa retreated. After this, it was agreed that the land between the Fish and Keiskamma rivers would be neutral territory.

British Settlers Arrive in 1820

The war from 1817–1819 led to a big wave of British settlers coming to the Cape. This had a huge impact. The governor, Lord Charles Somerset, wanted to create a barrier against the Xhosa. He planned to settle white colonists in the border area.

In 1820, the British parliament agreed to spend £50,000 to help people move to the Cape. About 4,000 British people emigrated. These immigrants became known as the 1820 Settlers. They formed the Albany settlement, which later included Port Elizabeth, and made Grahamstown their main town.

The British government hoped this plan would secure the frontier and provide jobs for unemployed people in Britain. But it did much more. These new settlers, from all parts of the United Kingdom, remained very loyal to Britain. Over time, they became a strong contrast to the Dutch colonists.

The arrival of these settlers also brought the English language to the Cape. English was first used in official rules in 1825. By 1827, it was used in court cases too. However, Dutch was not removed, and many colonists became bilingual.

Over the next few decades, there was tension between the eastern and western parts of the Cape Colony. The Eastern Cape, with its main port Port Elizabeth, did not like being ruled from Cape Town in the Western Cape. They often asked to become a separate colony. These disagreements ended in the 1870s. Prime Minister John Molteno changed the Cape government. He removed the last formal differences in 1873.

Dutch Disagreements with British Rule

Even though the colony was doing well, many Dutch farmers were unhappy with British rule. Their complaints were different from their earlier issues with the Dutch East India Company. In 1792, Moravian missionaries started helping the Khoikhoi people. In 1799, the London Missionary Society began trying to convert both Khoikhoi and Xhosa.

The missionaries supported the Khoikhoi's complaints. This made many colonists unhappy. In 1812, a rule was made that allowed magistrates to make Khoikhoi children work as apprentices. This was very similar to slavery. Meanwhile, the movement to end slavery was growing in England. The missionaries appealed to Britain for help.

An event from 1815 to 1816 made many Dutch frontiersmen permanently hostile to the British. A farmer named Bezuidenhout refused to obey a court order after a Khoikhoi complaint. He shot at the group sent to arrest him and was killed. This led to a small rebellion. The British executed five leaders of this rebellion in public.

In 1827, a new rule ended the old Dutch courts. Instead, resident magistrates were put in charge. This rule also said that all legal proceedings must be in English from then on.

Another rule in 1828 gave equal rights to the Khoikhoi and other free African people in the Cape. In 1830, a rule set harsh penalties for treating enslaved people badly. Finally, slavery was ended in 1834. Each of these rules made the Dutch farmers even angrier at the Cape government.

The small amount of money given to slave owners, and how it was paid, caused much anger. In 1835, farmers started moving into unknown lands again to escape the government they disliked. People had been moving beyond the colonial border for 150 years, but now it became a much larger movement.

Third Cape Frontier War (1834–1836)

On the eastern border, more trouble started between the government and the Xhosa people. The Cape government's policy towards them was very inconsistent. On December 11, 1834, a government group killed a high-ranking Xhosa chief. This made the Xhosa very angry.

An army of 10,000 men, led by Maqoma, the brother of the killed chief, swept across the border. They looted and burned homes and killed anyone who resisted. A group of freed Khoikhoi, who had settled in the Kat River valley in 1829, suffered greatly.

There were few soldiers in the colony. But Governor Sir Benjamin d'Urban acted quickly. All available forces were gathered under Colonel Sir Harry Smith. He reached Graham's Town on January 6, 1835, just six days after the news reached Cape Town. The British fought the Xhosa warriors for nine months. The fighting ended on September 17, 1836, with a new peace treaty. This treaty declared all the land up to the River Kei as British territory. Its inhabitants were declared British subjects. A place for the government was chosen and named King William's Town.

The Great Trek (1836–1840)

The British government did not approve of Sir Benjamin d'Urban's actions. The British Secretary for the Colonies, Lord Glenelg, said that "the great evil of the Cape Colony consists in its magnitude." He demanded that the border be moved back to the Fish River. He also had d'Urban removed from office in 1837.

Lord Glenelg's message on December 26 stated: "The Kaffirs had good reason for war; they had to resent, and tried fairly, though weakly, to get revenge for a series of invasions." This view of the Xhosa was one reason why the Voortrekkers left the Cape Colony.

The Great Trek, as it is called, lasted from 1836 to 1840. About 7,000 trekkers (Boers) founded new communities. These communities had a republican government beyond the Orange and Vaal rivers, and in Natal. British emigrants had already settled in Natal. From this time on, the Cape Colony was no longer the only European community in South Africa. However, it remained the most important for many years.

The emigrant Boers caused much trouble on both sides of the Orange River. The Boers, the Basothos, other native tribes, Bushmen, and Griquas fought for control. The Cape government tried to protect the rights of the native Africans. Missionaries, who had a lot of influence, advised the government. Several "native states" were recognized and supported by the Cape government. The goal was to create peace on the northern border. The first "Treaty States" recognized was Griqualand West of the Griqua people. More states were recognized between 1843 and 1844.

While the northern border became safer, the eastern border was in a bad state. The government was either unable or unwilling to settle disputes between Xhosa and Cape farmers.

However, the rest of the colony was making progress. Changing from enslaved labor to free labor helped farmers in the western provinces. A good education system was started, thanks to Sir John Herschel, an astronomer who lived in the Cape Colony from 1834 to 1838. Road Boards were set up and built many new roads.

A new stable industry, sheep-raising, was added to the existing ones like wheat-growing, cattle rearing, and wine making. By 1846, wool became the country's most valuable export. A legislative council was created in 1835, giving the colonists a say in their government.

War of the Axe (1846)

Another war with the Xhosa, called the War of the Axe or Amatola War, began in 1846. It started when a Khoikhoi escort was killed. He was transporting a Xhosa thief to Graham's Town for stealing an axe. A group of Xhosa attacked and killed the escort. The Xhosa refused to hand over the murderer. War was declared in March 1846.

The Ngqikas were the main tribe in the war, helped by the Ndlambe and Thembu. On June 7, 1846, General Somerset defeated the Xhosa at the Gwangu, near Fort Peddie. However, the war continued until Sandile, the Ngqika chief, surrendered. Other chiefs followed, and by the end of 1847, the violence stopped after 21 months of fighting.

British Power Expands (1847)

In December 1847, the last month of the War of the Axe, Sir Harry Smith arrived in Cape Town. He became the new governor of the colony.

Cape Colony's Borders Grow

Soon after arriving, he changed Lord Glenelg's policy. He decided to conquer neighboring lands. On December 17, 1847, he announced that the colony's borders would extend north to the Orange River and east to the Keiskamma river. This almost doubled the size of the Cape Colony.

He did this without asking the British Government, or the local Boers and African states. However, his plan to expand against the Xhosa gained him support from extreme colonists on the Eastern Cape frontier.

British Kaffraria is Formed

A few days later, on December 23, 1847, Sir Harry met with Xhosa chiefs. He announced that the land between the Keiskamma and the Kei Rivers was now British. This brought back territory that Lord Glenelg had given up. This land was not added to the Cape Colony. Instead, it became a separate British territory called British Kaffraria.

The Xhosa did not immediately fight against this. The governor had other important issues to deal with. These included establishing British control over the Boers beyond the Orange River and making friends with the Transvaal Boers.

Convict Protests and a New Government (1848–1853)

A big problem arose when it was suggested that the Cape Colony become a place for convicts. In 1848, Henry Grey, 3rd Earl Grey, the colonial secretary, asked governors if their colonies would accept certain types of convicts. He wanted to send Irish peasants, who had committed crimes due to the Great Famine, to South Africa.

Sir Harry Smith knew he was not popular with the Colonial Office. He had expanded the colony's territory without permission, which was expensive. Smith saw a chance to gain favor by allowing the Cape to be a convict station.

However, Smith did not ask the local people about this plan. The Cape prided itself on being a "free settlement" colony. So, when the first convict ship arrived, there was a huge protest. This started the convict crisis. Local people, already upset with Smith's rule, formed an anti-convict group. Its members promised not to interact with anyone involved in landing, supplying, or employing convicts.

The ship, named the Neptune, had 289 convicts, including the famous Irish rebel John Mitchel. Sir Harry Smith had the support of the extreme settlers in the Eastern Cape. He had helped them expand onto Xhosa lands. But he could not govern without the powerful Cape Town elite. They had all resigned from his Legislative Council.

Facing public resistance, he agreed not to let the convicts land. When the Neptune arrived in Simon's Bay on September 19, 1849, he kept them on board. He waited for orders to send them elsewhere. When the British government learned of the situation, they ordered the Neptune to go to Tasmania. It left after staying in Simon's Bay for five months.

The protests did not end there. They created a generation of local leaders who felt Britain did not understand their issues. This first mass movement in South Africa continued. It pushed for a free, representative government for the colony. The British government granted this, as Lord Grey had promised. A very liberal constitution was established in 1854. The first Cape Parliament was elected that same year.

Eighth Frontier War (1850–1853)

Soon after the anti-convict movement ended, the colony was at war again. The Xhosa were very angry about Sir Harry Smith's recent takeover of their lands. They had been secretly preparing to fight again since the last war.

Sir Harry Smith learned about the Xhosa preparations. He went to the border and called Sandile and other chiefs for a meeting. Sandile refused to come. So, in October 1850, the governor declared him removed from his leadership. He appointed an English magistrate, Mr. Brownlee, as temporary chief of the Ngqika tribe. The governor seemed to believe he could prevent a war and arrest Sandile without armed resistance.

On December 24, 1850, Colonel George Mackinnon was sent with a small army to arrest the chief. His men were attacked in a narrow gorge by many Xhosa gunmen. After some losses, Mackinnon's men were forced back under heavy fire. This small fight caused a general uprising among the entire Ngqika tribe.

Settlers in military villages along the border were caught by surprise. They had gathered to celebrate Christmas Day. Many were killed, and their houses were burned.

Other problems quickly followed. Most of the Xhosa police left, many taking their weapons. Encouraged by their first success, a large group of Xhosa troops surrounded and attacked Fort Cox. The governor was there with a small number of soldiers. Several attempts were made to kill Sir Harry. He began looking for ways to escape. Finally, he led 150 mounted riflemen, with Colonel Mackinnon, out of the fort. They rode 12 miles (19 km) to King William’s Town through heavy Xhosa fire.

Meanwhile, a new threat appeared. About 900 of the Kat River Khoikhoi, who had been strong allies of the British in past wars, joined their former enemies, the Xhosa. They had reasons for this. They complained that as soldiers in past wars, they had not been treated the same as others defending the colony. They received no payment for their losses. They felt they were a wronged and hurt people.

A secret agreement was made with the Xhosa to fight. Their goal was to remove the Europeans and create a Khoikhoi republic. Within two weeks of the attack on Colonel Mackinnon, the Kat River Khoikhoi also took up arms. Their revolt was followed by Khoikhoi at other missionary stations. Some Khoikhoi from the Cape Mounted Rifles, including some who had escorted the governor from Fort Cox, also joined. But many Khoikhoi remained loyal, and the Fingo people sided with the Cape government.

After the initial confusion, Sir Harry Smith and his forces turned the war against the Xhosa. The Amatola Mountains were stormed. Sarhili, the highest-ranking chief, who had secretly helped the Ngqika, was severely punished. In April 1852, Earl Grey recalled Sir Harry Smith. He accused him of not being energetic enough in the war, which the Duke of Wellington disagreed with. Lieutenant-General Cathcart replaced him.

Sarhili was attacked again and forced to surrender. The Amatolas were cleared of Xhosa fighters. Small forts were built to prevent them from returning.

The British commanders faced challenges due to their limited equipment. It was not until March 1853 that this largest of the Frontier wars ended. Several hundred British soldiers were lost. Shortly after, British Kaffraria became a crown colony. The Khoikhoi settlement at Kat River remained, but the Khoikhoi's power within the colony was broken.

Xhosa Cattle-Killing and Famine (1854–1858)

In 1854, a cattle disease called "lung sickness" spread among the Xhosa cattle. This disease came to South Africa with infected animals brought by settlers from the Netherlands in 1853. Many cattle died.

In April 1856, two girls, one named Nongqawuse, went to scare birds from the fields. When she returned, she told her uncle Mhlakaza that she had met three spirits. They told her that all cattle should be killed and all crops destroyed. The spirits said that after this, the dead Xhosa would return and help drive out the white people. The ancestors would bring new, healthy cattle to replace those that were killed. Mhlakaza believed the prophecy and told the chief Sarhili.

Sarhili ordered the spirits' commands to be followed. At first, the Xhosa were told to destroy their fat cattle. Nongqawuse, standing in the river where the spirits first appeared, heard strange noises. Her uncle interpreted these as orders to kill more and more cattle. Eventually, the spirits commanded that no animal should be left alive, and every grain of corn should be destroyed.

If this was done, on a certain date, countless beautiful cattle would come from the earth. Huge fields of ripe corn would instantly appear. The dead would rise, sickness would vanish, and everyone would become young and beautiful. Unbelievers and white people would die that day. Large kraals (cattle enclosures) were prepared for the promised cattle. Huge skin sacks were made for the milk, which was expected to be more plentiful than water.

Finally, the day arrived that was supposed to bring a paradise on Earth. The sun rose and set, but the expected miracle did not happen.

This movement ended by early 1858. By then, about 40,000 people had died from starvation. Over 400,000 cattle had been slaughtered.

Sir George Grey's Time as Governor (1854–1870)

Sir George Grey became governor of the Cape Colony in 1854. The colony grew a lot under his leadership. He thought the British government's policy of not governing beyond the Orange River was wrong. In 1858, he suggested a plan for a confederation that would include all of South Africa. However, Britain rejected it as impractical.

Sir George kept a British road open through Bechuanaland to the far interior. He gained the support of missionaries Robert Moffat and David Livingstone. Sir George also tried to educate the Cape Xhosa and establish British authority among them. The Xhosa's self-destruction made this easier. Beyond the Kei River, the Transkei Xhosa were left alone.

Sir George Grey left the Cape in 1861. During his time as governor, the colony's resources increased. Copper mines opened in Little Namaqualand. The mohair wool industry was started. Natal became a separate colony.

In November 1863, a railway opened from Cape Town to Wellington. In 1860, a large breakwater was built in Table Bay. This was much needed on that dangerous coast. These marked the start of large-scale public works in the colony. They were a direct result of the colony gaining more control over its own government.

The area of British Kaffraria was added to the colony in 1865. It became the Electoral Divisions of King William’s Town and East London. This transfer also removed the ban on selling alcoholic beverages to native people. The free trade in alcohol that followed had very bad results among the Xhosa tribes.

A severe drought affected almost the entire colony for several years. This caused a major economic downturn, and many farmers suffered greatly. It was during this period, in 1869, that ostrich-farming successfully became a separate industry.

Whether the British government wanted it or not, British authority continued to spread. The Basotho people, who lived in the upper valleys of the Orange River, had been under British protection from 1843 to 1854. But when the Orange sovereignty was abandoned, they fell into a long, tiring war with the Boers of the Orange Free State.

Their chief Moshesh urgently asked for help. In 1868, the Basotho were declared British subjects. Their territory became part of the Cape Colony in 1871 (see Basutoland). In the same year, the southeastern part of Bechuanaland was added to Britain. It was named Griqualand West. This happened because rich diamond mines were discovered there. This discovery would have huge impacts in the future.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |