History of the Cyclades facts for kids

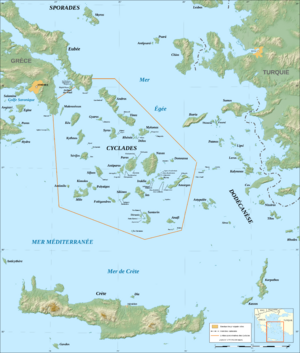

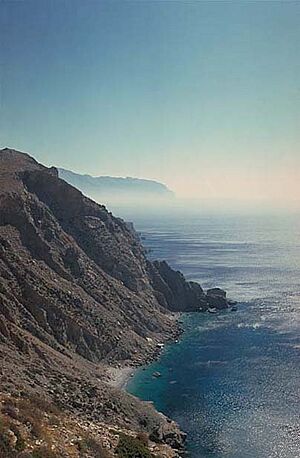

The Cyclades are a group of Greek islands in the southern Aegean Sea. There are about 2,200 islands, small islets, and rocks. Only 33 of these islands have people living on them. Ancient Greeks believed these islands formed a circle (kyklos in Greek) around the special island of Delos. That's how they got their name!

Some of the most famous islands are Andros, Tinos, Mykonos, Naxos, Amorgos, Syros, Paros and Antiparos, Ios, Santorini, Milos and Kimolos. There are also smaller ones like Irakleia, Schoinoussa, Koufonisi, Keros and Donoussa.

These islands are located where Europe, Asia Minor, and Africa meet. In ancient times, ships sailed close to the coast, always keeping land in sight. So, the Cyclades were very important stops for traders. This location brought them wealth through trade, but also trouble, as many groups wanted to control these important sea routes.

Many people see the Cyclades as one big unit. The islands look similar in their land features, and you can often see one island from another. The dry climate and soil also make them seem connected. Even though they have different histories, these islands share a unique identity.

The islands have been home to people since the Neolithic period (New Stone Age). Their natural resources and location helped a great culture grow in the 3rd millennium BC: the Cycladic civilisation. Later, powerful groups like the Minoans and Mycenaeans influenced them. The Cyclades became important again during the Archaic period (8th – 6th century BC).

The Persians tried to take the islands, but failed. Then, the Cyclades joined the Delian League with Athens. Later, different kingdoms fought over them, and Delos became a major trading center. Trade continued during the Roman and Byzantine Empires, but it also attracted pirates.

After the Fourth Crusade, the Cyclades came under Venetian control. Western lords created small kingdoms, with the Duchy of Naxos being the largest. The Ottoman Empire later conquered the Duchy, but allowed the islands some freedom. The islands stayed wealthy despite pirates. In the 1830s, the Cyclades became part of Greece. They had a time of trade success, but then trade routes changed. After many people moved away, tourism helped the islands grow again.

Contents

Ancient Life: Early Settlements and Tools

The very first signs of human activity in the Cyclades were found not on the islands themselves, but on the mainland. In a cave called Franchthi, scientists found obsidian (a sharp volcanic glass) from Milos island. This obsidian dates back to about 11,000 BC. This shows that people were already sailing and trading across 150 kilometers of sea!

Permanent homes on the islands started when people learned to farm and raise animals. The oldest known settlements are on the islet of Saliagos, between Paros and Antiparos, and at Kephala, Kea. These date back to the 5th millennium BC.

On Saliagos, people built stone houses without mortar. They also made small Cycladic statues. At Kephala, studies of ancient bones show that people lived to about 20 years old. Women often lived shorter lives than men.

People had different jobs. Women cared for children, harvested crops, looked after small animals, and made pottery and baskets. Men did heavier farm work, hunted, fished, and worked with stone, bone, wood, and metal. The richest tombs from this time, called cist tombs, belonged to men. Pottery was shaped by hand and decorated with fingernails or brushes.

The Amazing Cycladic Civilization

Around the end of the 1800s, an archaeologist named Christos Tsountas found many ancient objects on different Cycladic islands. He realized they were all part of one culture from the Bronze Age (3rd millennium BC), which he called the Cycladic civilization. This civilization is famous for its beautiful marble statues, called idols. These idols have been found far away, even in Portugal, showing how active and widespread this culture was.

The Cycladic civilization is a bit older than the famous Minoan civilisation on Crete. In fact, the Minoans learned some things from the Cycladic people, like their art styles.

Historians divide the Cycladic civilization into three main periods:

- Early Cycladic I (3200-2800 BC)

- Early Cycladic II (2800-2300 BC) - This was the peak of their culture.

- Early Cycladic III (2300-2000 BC)

Studies of skeletons from this time show that people's diets improved. Men lived longer, up to 40 or 45 years, but women still lived shorter lives (around 30 years). Jobs were still divided between men and women. Farming included grains (mostly barley), grapes, and olives. People raised goats, sheep, and some pigs. Fishing, especially for tuna, was also important. There was more wood back then, which was used for houses and boats.

The Cycladic people were excellent sailors and traders. They lived near the coast and used their islands' location to their advantage. It seems they exported more goods than they imported, which was unusual for the region. Pottery found on islands like Milos and Santorini shows that trade routes connected mainland Greece to Crete, passing through the Cyclades.

There were skilled workers like metalworkers, potters, and sculptors. Obsidian from Milos was still the main material for tools because it was cheaper than metal. Early bronze tools, made from copper and arsenic, have been found. Copper came from Kythnos. Tin, used in later bronze, came from far away, showing that the Cyclades traded with places like Troad (in modern-day Turkey).

They used tools to work with marble from Naxos and Paros, creating their famous idols and marble vases. They also used emery from Naxos for polishing and pumice stone from Santorini for a smooth finish.

Over time, people moved their settlements away from the coast to higher, fortified places on the islands' hills. This might have been because of early pirates.

Minoan and Mycenaean Influence

During the 2nd millennium BC, the Cretans (Minoans) took control of the Cyclades. Then, around 1450 BC, the Mycenaeans from mainland Greece took over. The islands were too small to fight against these powerful empires.

Stories from Ancient Writers

The ancient writer Thucydides wrote that King Minos of Crete drove out the first people of the Cyclades, called the Carians. Herodotus added that the Carians were Minos's subjects and were known as Leleges. They were independent but provided sailors for Minos's ships. Herodotus also said the Carians were great warriors and taught the Greeks how to put plumes on helmets and designs on shields.

Later, the Dorians pushed the Carians out, and then the Ionians arrived. The Ionians made Delos a very important religious center.

Cretan (Minoan) Influence

About 15 Minoan settlements from the Middle Cycladic period (around 2000-1600 BC) are known. The Minoans didn't just conquer; they influenced the culture. Cycladic idols disappeared from tombs, but the tombs themselves didn't change much.

The northern Cyclades became more like the Northeast Aegean cultures, while the southern islands were closer to the Cretan civilization. Crete's influence grew stronger from about 1700 BC. Minoan pottery, building styles (like skylights and frescoes), and writing (Linear A) have been found on islands like Kea, Milos, and Santorini.

It's hard to say exactly what the Minoan presence was like. Were they settler colonies, protectorates, or just trading posts? Some thought the big buildings on Santorini (Akrotiri) or Milos (Phylakopi) might have been palaces for foreign rulers, but there's no clear proof. It seems Crete protected its trade routes through agents who had some political power. The islands of Kea, Milos, and Santorini were especially important for trade. Kea was a first stop from the mainland, Milos was a source of obsidian, and Santorini was a key link for Crete.

Most bronze was still made with arsenic, not tin. Tin was introduced slowly, mostly in the northeast Cyclades.

The settlements were small villages of sailors and farmers, often strongly fortified. Houses were usually rectangular, with one to three rooms, and sometimes had an upper floor. They were modest and built close together, separated by paved lanes. There were no grand palaces or "royal tombs" like on Crete. Even though the islands kept some political and trade freedom, Cretan religious influence was very strong. Religious objects and fresco themes found on Santorini and Milos are similar to those in Cretan palaces.

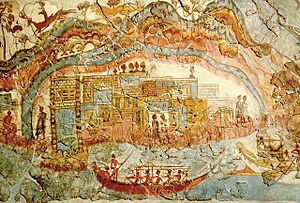

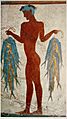

The famous volcanic eruption on Santorini (around 1600 BC) buried and preserved the city of Akrotiri. This city had paved streets with drains and two- or three-story buildings. The ground floors were for storage or workshops, and upper floors were decorated with frescoes.

Archaeologists found that Akrotiri was damaged by an earthquake before the eruption. The site of Aghia Irini on Kea was also destroyed by an earthquake around the same time. After the eruption, Minoan goods stopped coming to Aghia Irini and were replaced by Mycenaean goods.

Mycenaean Control

From the mid-15th century BC to the mid-11th century BC, the Cyclades had three phases of relations with mainland Greece. Around 1250 BC, Mycenaean influence was mainly on Delos, Kea, Milos, and Naxos. Some buildings resembled mainland palaces, and Mycenaean religious items were found.

When the mainland Mycenaean kingdoms faced troubles, relations with the islands cooled. Some islands built or improved their defenses. Later, relations restarted, with people and goods moving from the mainland to the islands. A Mycenaean-style tomb was found on Mykonos. The Cyclades remained settled until the Mycenaean civilization declined.

Classical and Hellenistic Eras

Ionian Arrival and Growth

The Ionians came from the mainland around the 10th century BC. About 300 years later, they built the important religious sanctuary on Delos. Early Cycladic cities like those on Kea and Andros were built between the 12th and 8th centuries BC. Pottery shows that different islands had different connections. Naxos and Andros were linked to Euboea, while Milos and Santorini were influenced by the Dorians.

From the 8th century BC, the Cyclades became very prosperous. This was thanks to their natural resources: obsidian from Milos, silver from Sifnos, pumice from Santorini, and marble from Paros. The islands were so wealthy that they didn't need to send many people to establish new colonies, except for Santorini, which helped found Cyrene in Libya. They showed off their wealth by building grand structures in famous sanctuaries, like the treasury of Sifnos at Delphi.

Persian Wars and Athenian Control

The wealth of the Cyclades attracted attention. In 524 BC, forces from Samos attacked Sifnos. The Persians tried to take the Cyclades in the early 5th century BC. They sacked Naxos, but spared Delos for religious reasons. Some islands, like Sifnos and Milos, surrendered.

During the Greco-Persian Wars, some Cycladic ships fought alongside the Greeks at the Battle of Salamis. This earned them a place on a special monument at Delphi. After the wars, Themistocles punished islands that had sided with the Persians, which led to Athens's control.

In 479 BC, some Cycladic cities fought with other Greeks at the Battle of Plataea.

Athens then formed the first Delian League, an alliance to fight the Persians. Cycladic cities either provided ships or paid tribute in silver. The money was kept on Delos. However, Athens soon became very controlling. Naxos revolted in 469 BC and was turned into a subject state. The League's treasury was moved from Delos to Athens. The Cyclades became part of Athens's "island district" and paid silver tribute. Athens sometimes sent its own citizens to settle on islands like Naxos and Andros.

By the start of the Peloponnesian War, most Cyclades, except Milos and Santorini, were under Athenian rule. They paid tribute until 404 BC. After a short period of freedom, they again came under Athenian control in the second Delian League.

Hellenistic Kingdoms and Delos's Rise

In the Hellenistic era, different kingdoms fought over the Cyclades. Leaders often claimed they wanted to "free" the Greek cities, but really they wanted to control them.

In 314 BC, Antigonus I created the Nesiotic League around Tinos. Later, the Egyptian fleet of Ptolemy I "freed" Andros. The islands then came under Ptolemaic rule. After a battle, they were given to Macedon. However, Macedon couldn't fully control them, leading to instability. Later, Philip V of Macedon took control and placed soldiers on islands like Andros and Paros.

After the Battle of Cynoscephalae, the islands passed to Rhodes, and then to the Romans. Rhodes helped the Nesiotic League grow again.

Society in this period was often led by wealthy farming families. People tended to marry within their social class or even within their own city. Delos, for example, had many foreigners, but its citizens mostly married each other.

The Hellenistic era left many towers on the Cyclades, especially on Amorgos, Sifnos, and Kea. These towers might have been for observation or to protect valuable resources like minerals or crops. They show the islands' prosperity during this time.

Delos, once just a religious site, became a huge trading power. In 314 BC, it gained independence. Banking and trade, especially in wheat and slaves, grew quickly. In 167 BC, Delos became a free port, meaning no customs taxes were charged. This led to a massive trade boom, especially after Rome destroyed its rival, Corinth, in 146 BC. Merchants from all over the Mediterranean came to Delos. It's estimated that Delos had about 25,000 people in the 2nd century BC.

The "agora of the Italians" was a large slave market. Wars and pirates supplied many slaves. While some sources claim 10,000 slaves were sold daily, this might just mean "many." Some "slaves" were actually war prisoners or kidnapped people whose ransoms were paid quickly.

Delos's wealth also attracted pirates. In 298 BC, Delos paid Rhodes for "protection against pirates." This shows how dangerous the seas were.

Roman and Byzantine Rule

The Cyclades Under Rome

Rome got involved in Greece for many reasons, including helping cities and fighting powerful kings. After a victory, Rome declared Greece "free." Delos became a free port under Roman protection in 167 BC, which benefited Italian merchants. The Greek city system continued under the Roman Empire.

The Cyclades were part of a Roman province, either Asia or Achaea. Later, under Emperor Vespasian, they became a Roman province. Under Diocletian, they were part of a "province of the islands."

Christianity spread early in the Cyclades. Catacombs (underground burial places) on Milos show a Christian community existed there by the 3rd or 4th century.

From the 4th century, the islands faced new dangers. In 376, the Goths attacked the archipelago.

Byzantine Period

When the Roman Empire split, the Cyclades became part of the Byzantine Empire and remained so until the 13th century.

The Byzantine Empire organized its lands into "themes" (military districts). The "theme of the Aegean Sea" included the Cyclades. This theme provided sailors for the Byzantine navy. Over time, the central government's control over the islands weakened, making defense and tax collection difficult.

In 727, the islands revolted against Emperor Leo III. Later, in 769, the Slavs attacked the islands.

From the early 9th century, Saracen pirates from Crete threatened the Cyclades for over a century. Naxos had to pay them tribute. Some islands, like Paros, became almost empty. In 904, Arab fleets pillaged Andros, Naxos, and other Cycladic islands.

During this time, villages moved from the coast to higher ground in the mountains, like Lefkes on Paros. This was to escape pirates. But it also helped develop fertile inland plains. For example, silk farming, which made Andros wealthy, was introduced in the 11th century.

The Duchy of Naxos

In 1204, the Fourth Crusade captured Constantinople. The winners divided the Byzantine Empire. The Venetians claimed the Cyclades, but couldn't afford to send an army. So, they said anyone who could take and manage the islands could have them.

A wealthy Venetian named Marco Sanudo took Naxos in 1205. By 1207, he and his friends controlled most of the Cyclades. Sanudo founded the Duchy of Naxos, which included major islands like Naxos, Paros, Milos, and Syros. The Dukes of Naxos became vassals of the Latin Emperor of Constantinople in 1210. They brought the Western feudal system to the islands. Venice benefited because the islands were cleared of pirates, making trade routes safer. People started moving back to the coasts, and their new lords built fortifications.

The laws of the Principality of Achaea, called the Assizes of Romania, became the basis for laws on the islands. The feudal system created a powerful local elite. "Frankish" (Western) nobles built castles and lived like lords. They often married each other, and land was divided through dowries and inheritances.

However, this Western feudal system was layered on top of the existing Byzantine system. Taxes and forced labor were based on Byzantine divisions, and farming continued with Byzantine methods. Byzantine property and marriage laws also stayed for the local Greek people. In religion, Catholic leaders were in charge, but Orthodox leaders continued to exist. The two cultures mixed closely, seen in things like embroidery designs.

In the late 1200s, the Byzantine Empire tried to retake the Aegean. They failed to take Paros and Naxos, but did conquer some islands. In 1292, Roger of Lauria attacked Andros, Tinos, Mykonos, and Kythnos. In the early 1300s, the Catalans appeared, followed by the Turks. As the Seljuk Empire declined, Turkish groups started raiding the islands from 1330, taking people as slaves. This caused the population to shrink. Even when the Ottomans took over Anatolia, the raids continued until the mid-1400s.

The Duchy of Naxos was briefly under Venetian protection in the early 1500s.

Ottoman Rule

Hayreddin Barbarossa, the Grand Admiral of the Ottoman Navy, conquered the Cyclades for the Turks in 1537 and 1538. Tinos, which had been Venetian since 1390, was the last to fall in 1715.

The Ottoman Empire couldn't leave soldiers on every island. So, they often let the existing ruling families stay in power, as long as they paid an annual tax. The largest islands kept their Latin lords, who became vassals of the Ottomans. Four smaller islands came under direct Ottoman rule.

When the last Duke of Naxos died, the islands gradually came under normal Ottoman administration. Their income went to the Kapudan Pasha (grand admiral). He visited once a year with his fleet to collect taxes.

The Ottomans rarely sent their own governors to the islands. Local Christian leaders, called epitropes, governed and collected taxes. In 1580, the Ottomans gave special privileges to the larger Cycladic islands. In exchange for tribute and military protection, Christian landowners kept their lands and power.

This led to a unique local law, mixing feudal customs, Byzantine traditions, Orthodox church law, and Ottoman rules. This complex system meant only local authorities could handle cases. Documents were a mix of Italian, Greek, and Turkish.

Population and Economy

The Cyclades suffered greatly from pirate attacks, first by Turks, then by Christians. After a major defeat, Uluç Ali Reis, the new Kapudan Pasha, started a plan to repopulate the islands. For example, in 1579, people were allowed to settle on the nearly empty island of Ios. Kimolos, attacked by pirates in 1638, was repopulated with people from Sifnos.

Pirates also brought diseases. The plague hit Milos in 1687, 1688, and 1689, killing many people. In 1704, the plague and anthrax killed almost all the children on Milos.

Few Turks moved to the islands because there was no land given to Muslim settlers, and the Turks weren't very interested in the sea. Only Naxos had a few Turkish families.

The Cyclades had limited resources and relied on imports for food. Larger islands like Naxos and Paros were more fertile due to their mountains and coastal plains.

The islands produced goods for trade, sharing resources. Santorini's wine, Folegandros's wood, Milos's salt, and Sikinos's wheat were traded within the archipelago. Andros raised silkworms, and Tinos and Kea spun the silk. Some products were exported further, like Milos's millstones to France and Sifnos's straw hats to the West.

The Cyclades were also a center for illegal wheat trade to the West. This trade brought large profits in good years.

Commercial activity remained vital. Some traders specialized in buying pirate loot and supplying pirates. Islands like Milos, Mykonos, and Kimolos became pirate havens, benefiting from their presence. This created a difference between "piratical" islands and "law-abiding" ones, like Sifnos, which opened the first Greek school in the Cyclades in 1687.

During wars between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, the Cyclades were often caught in the middle. The Venetians exploited them, leading to the saying, "Better to be massacred by the Turk than be given as fodder to the Venetian." When the Venetians retreated, they often destroyed forests and stole livestock, causing more suffering.

Orthodox vs. Catholic

The Ottoman Sultan favored the Greek Orthodox Church. The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople was seen as the leader of the Greeks in the Empire. This allowed the Orthodox Church to regain influence lost during the Latin (Catholic) rule. Many new Orthodox monasteries were founded, often by wealthy Greek Orthodox families who gained land and wealth during this period. By the early 1600s, the Orthodox Church had largely re-established itself.

Catholic missionaries, supported by France and Venice, tried to convert the Greek Orthodox to Catholicism. They also tried to make existing Catholics follow the Tridentine Mass. There were six Catholic bishoprics in the Cyclades, even though there were very few Catholics in some areas.

Capuchin and Jesuit missionaries set up houses on various islands. The Jesuits even staged plays to attract Greeks, performing them in the local language.

By the 1700s, most Catholic missions had failed, except on Syros, which still has a strong Catholic community today. On Santorini and Naxos, small Catholic communities remained. These Catholic groups often lived separately from the Orthodox and dealt directly with Ottoman authorities. This made them feel surrounded by the "Orthodox enemy."

Piracy and Western Influence

After North Africa joined the Ottoman Empire, Barbary pirates moved to the Western Mediterranean. Christian pirates then took over in the Aegean. Their main target was the trade route between Egypt and Constantinople. Pirates spent winters on islands like Paros, Ios, or Milos. In spring and summer, they attacked ships near Samos, Cyprus, and Syria, often kidnapping wealthy Muslims for ransom. They spent their loot in the Cyclades during winter.

Famous pirates like the Téméricourt brothers and Hugues Creveliers, known as "the Hercules of the seas," operated here. They were often supported unofficially by Western powers like Malta, Venice, or France, who wanted to maintain a presence in the region. These pirates were sometimes seen as privateers (legal pirates working for a government) but could easily become outlaws.

There were close ties between Catholic pirates and Catholic missions. Monks protected pirates and received generous donations from them. This helped the missions against the Turks and the growing Orthodox Church.

By the early 1700s, Western pirates disappeared, replaced by local islanders involved in piracy, smuggling, and trade. This led to the rise of great shipping fortunes.

Decline of Ottoman Rule

Life under Ottoman rule became harder. The initial benefits of Ottoman rule faded. The 1580 agreement had given the islands administrative, tax, and religious freedoms, including the right to ring church bells, which was rare for Greeks under Ottoman rule.

Ideas from the Age of Enlightenment reached the Cyclades through traders. Some islanders even sent their sons to study in Western universities. Legends about Greek liberation and the reconquest of Constantinople circulated, often involving a "blond race" of liberators from the North, which led Greeks to look to Russia for help.

Russia, seeking access to warm-water ports, used these legends to its advantage. Empress Catherine even named her grandson Constantine, hoping he would lead the reconquest.

The Cyclades took part in uprisings, like the Orlov Revolt (1770-74), which brought Russians to the islands. In 1770, the Russian navy defeated the Ottoman navy at Chesma and wintered in Naoussa Bay on Paros. Russians stayed in the Cyclades for several years.

Another Russo-Turkish war (1787-1792) also involved the Cyclades. A Greek officer in the Russian navy, Lambros Katsonis, attacked Ottoman ships from Kea. He was eventually defeated off Andros.

However, the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) allowed the islands to develop trade under Russian protection, and they were largely spared from Ottoman revenge.

The Cyclades in Modern Greece

War of Independence

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca helped the Greek islands prosper. Andros, for example, built its own merchant fleet. This prosperity made Ottoman rule seem less acceptable.

For the Cyclades' Catholics, the situation was complex. Ottoman rule wasn't terrible, but the Ottomans were seen as enemies of Christianity. If the revolution failed, there would be harsh revenge. But if it succeeded, living in a mostly Orthodox state was also a concern. Catholics didn't join the fight, especially after the Pope declared neutrality.

The Greek War of Independence began in March 1821. The Cyclades had mixed feelings. The war brought new piracy (under patriotic excuses), "revolutionary taxes," and social unrest. The French flag flew over Catholic churches on Naxos, protecting them from Orthodox anger.

The Cyclades participated in the conflict only sometimes. Andros, Tinos, and Anafi used their fleets to help the Greek cause. Mado Mavrogenis from Mykonos used her wealth to supply ships. Orthodox Greeks from Naxos formed a troop that fought the Ottomans. Paros sent soldiers to the Peloponnese.

Massacres on Chios and Psara (1824) led to many refugees fleeing to the Cyclades. Syros, in particular, saw a huge influx of refugees, which changed its population and city structure. The Catholic island became more Orthodox.

At the end of the war, in 1832, the Cyclades became part of the new Greek kingdom under King Otto. France had been interested in acquiring them to protect Catholics, but they ultimately went to Greece.

Economy and Society in the 19th Century

The marble quarries of Paros, unused for centuries, reopened in 1844 to supply marble for Napoleon's tomb.

Syros became very important for Greek trade and transport in the late 1800s. It was protected during the War of Independence and its rivals, like Hydra, were ruined. Ermoupolis on Syros was Greece's largest port and an industrial center. The first strike in Greece happened there in 1879, when tannery and shipyard workers demanded higher wages.

However, when the Corinth Canal opened in 1893, Syros and the Cyclades declined. Steamships made them less vital as stopovers. The lack of railroads also hurt them.

The silkworm disease in the 1800s severely damaged the economies of Andros and Tinos. Many islanders moved away. People from Anafi, for example, moved to Athens and built a neighborhood there called Anafiotika, still standing today.

The failure of the Cretan uprising in 1866-67 brought many refugees to Milos. They settled on the coast and created a new port, Adamas.

Population growth in the Cyclades was slow compared to the rest of Greece in the late 1800s. Ermoupolis lost many residents as the Corinth Canal opened and Piraeus grew.

After the Greek defeat in Asia Minor in 1922, many Greek refugees fled to the Cyclades before moving to other parts of Greece.

In the 1950s, many people left the Cyclades for Athens or abroad, seeking better living conditions and work.

20th-Century Economy (Beyond Tourism)

In the mid-1930s, the Cyclades had a population density similar to the national average.

While tourism wasn't yet dominant, the islands had other resources. Naxos's emery was mined for export. Sifnos, Serifos, Kythnos, and Milos provided iron ore. Santorini had volcanic ash (pozzolana), Milos had sulfur, and Antiparos and Sifnos had zinc. Syros remained an important export port.

Large deposits of bauxite (used for aluminum) were found on Amorgos, Naxos, Milos, Kimolos, and Serifos. Amorgos's bauxite was mined in 1940.

The exhaustion of iron ore on Kythnos led to significant emigration in the 1950s.

Andros was one of the few shipping islands that adapted to steam engines. It supplied many sailors to the Greek Navy until the 1960s-1970s.

Today, the Cyclades still have natural resources beyond tourism. Agriculture is important on some islands, like Naxos. They produce and export wine, figs, olive oil, citrus fruits, and vegetables (like the famous Naxos potato). Sheep, goats, and some cows are raised. Mineral resources include marble (Paros, Tinos, Naxos), emery (Naxos), manganese (Mykonos), iron, and bauxite (Serifos). Milos has large open-air mines for sulfur, alum, barium, perlite, kaolin, bentonite, and obsidian. Syros still has shipyards, metal industries, and tanneries.

World War II: Famine and Resistance

The Italian attack on Greece in 1940 began with the torpedoing of a Greek ship in Tinos Bay. Italy wanted to create an "Italian Province of the Cyclades."

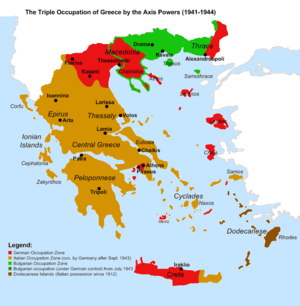

When Germany attacked Greece in April 1941, the Cyclades were occupied later than the mainland, mostly by Italian troops. Milos was taken by Germans. This delay allowed politicians like George Papandreou to stop on Tinos before going to Egypt to continue the fight.

After Italy surrendered in September 1943, Germany ordered its forces to take over Italian-held islands. Churchill wanted to take the Dodecanese islands to pressure Turkey to join the Allies. British troops took some islands, but the German counter-attack was strong. General Müller took island after island, leading to the Cyclades being under German occupation.

Like the rest of Greece, the Cyclades suffered from a terrible famine organized by the German occupiers. Fishing was banned. On Tinos, hundreds died of hunger. Naxos, which relied on Athens for supplies, lost ships and faced starvation. On Syros, deaths increased dramatically, and births decreased.

Greek Resistance groups formed on each island. Because of their isolation, they couldn't fight large-scale guerrilla wars like on the mainland. However, in spring 1944, Greek and British commandos raided German garrisons. For example, the SBS raided Santorini, and the Sacred Band attacked the aerodrome on Paros. Mykonos was liberated in September 1944. Milos, however, remained under German control until May 1945.

Exile Islands Again

During various dictatorships in the 20th century, the Cyclades, especially Gyaros, Amorgos, and Anafi, were again used as places of exile for political opponents.

From 1918, royalists were sent there. In 1926, Communists were exiled to the islands.

During the Metaxas dictatorship (1936–1940), over 1,000 opponents were deported to the Cyclades. On some islands, the exiles outnumbered the locals. This was a way to avoid overcrowding mainland prisons and to control prisoners more easily. Unlike in prisons, exiles had to find their own shelter and food, making it cheaper for the government. Empty houses on islands, due to rural exodus, were rented to the exiles. Poor exiles received a small daily allowance.

Exiles created their own social organizations to survive. They formed "communes" with treasurers and secretaries who organized debates. They had strict rules for how they interacted with islanders, for things like rent and food. Work was shared among them.

In 1968, 5,400 opponents of the military junta were deported to Gyaros.

Governments in the 1950s and 60s often didn't improve ports and roads on smaller islands. Islanders saw this as a way to keep them isolated for exiles, which made them dislike Athens. Amorgos, for example, only got electricity in the 1980s and paved roads in 1991. This also slowed down tourism development.

Tourism Development

Greece has been a tourist destination for a long time. It was part of the "Grand Tour" for early British tourists.

In the early 1900s, the main tourist attraction in the Cyclades was Delos, due to its ancient history. Guidebooks only mentioned Syros, Mykonos, and Delos. Syros was the main port, and Mykonos was a stop before Delos. Syros had two hotels, while Mykonos had guesthouses.

By 1933, Mykonos received over 2,000 visitors.

Mass tourism to Greece really took off in the 1950s. After 1957, tourism revenue grew rapidly, soon surpassing that from tobacco, Greece's main export.

Today, tourism in the Cyclades varies. Some islands, like Naxos (with its farming and mining) or Syros (with its commercial and administrative roles), don't rely only on tourism. But for small, dry islands like Anafi or Donoussa, tourism is crucial for survival.

In 2005, the Cyclades had many hotels. Santorini and Mykonos were the top destinations, followed by Paros and Naxos. Most hotels were two-star. The Cyclades have a high "tourist load" (beds per square kilometer or per inhabitant), especially on Mykonos, Paros, Ios, and Santorini.

In 2006, the Cyclades received 310,000 visitors, with 1.1 million overnight stays. This number has remained stable, even as overall tourism to Greece has fallen, showing the Cyclades' continued appeal.

Since the 2000s, more Greek tourists have visited the Cyclades. In 2006, 60% of Santorini's tourists were Greek. Greeks tend to plan their trips later but return more often than foreign tourists.

Images for kids

-

Akrotiri, Santorini, the Fisherman.

-

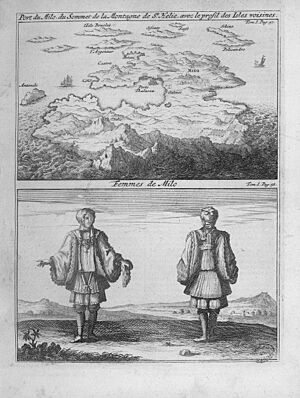

Delos in 1829 (A. Blouet, Morea expedition).

-

Milos in 1829 (A. Blouet, Morea expedition).

-

Portara on Naxos in 1829 (Abel Blouet, Morea expedition).

-

Map of Santorini in 1848.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de las Cícladas para niños

In Spanish: Historia de las Cícladas para niños

- Cyclades

- Cycladic civilization

- Duchy of the Archipelago

- Mosaics of Delos

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |