Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hugh O'Neill

Aodh Ó Néill |

|

|---|---|

| Earl of Tyrone | |

| Tenure | 1587–1607 |

| Predecessor | Turlough Luineach O'Neill |

| Successor | Henry O'Neill |

| Born | c. 1550 |

| Died | 20 July 1616 (aged about 76) Rome, Italy |

| Buried | San Pietro in Montorio, Rome |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Issue Detail |

Hugh, Henry, Alice, & others |

| Father | Matthew O'Neill |

| Mother | Siobhán Maguire |

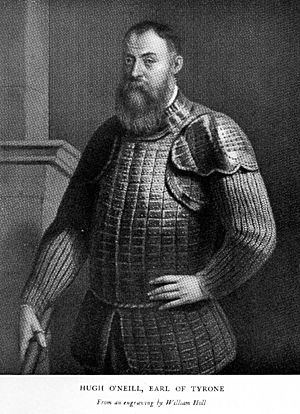

Hugh O'Neill (in Irish: Aodh Mór Ó Néill, meaning Hugh the Great O'Neill; born around 1550 – died July 20, 1616) was a powerful Irish Gaelic leader. He was known as the Earl of Tyrone and later became The Ó Néill Mór, which means the Chief of his family name.

Hugh O'Neill lived during the time when England, ruled by the House of Tudor, was trying to take full control of Ireland. He is most famous for leading a group of Irish clans in a major conflict called the Nine Years' War. This war was the biggest challenge to English rule in Ireland since the time of Silken Thomas and King Henry VIII.

Contents

Hugh O'Neill's Early Life and Family

Hugh O'Neill belonged to the O'Neill dynasty, a very old and important Irish family. The English government saw his family line as the rightful leaders of the O'Neills and the Earls of Tyrone. Hugh was the second son of Matthew O'Neill. Matthew was thought to be the son of Conn, the 1st Earl of Tyrone.

Shane O'Neill, another son of Conn O'Neill, argued that Matthew was not a true son. This led to a fight over who would be the next leader. Matthew was killed by Shane's supporters, leaving Hugh and his brother Brian in danger. The English government in Dublin Castle supported Hugh and Brian. They wanted to use them to weaken the powerful O'Neill lords in Ulster.

The English had a plan called surrender and regrant. This meant Irish clan chiefs had to give their lands to the English Crown. Then, the Crown would give the lands back to them as English property. This way, the English legal system would control the lands, not the old Irish family rules.

Becoming Baron of Dungannon

Hugh's brother, Brian, was killed in 1562 by Turlough Luineach O'Neill, Shane's chosen successor. Hugh then became the Baron of Dungannon. In 1585, Hugh O'Neill was officially named Earl of Tyrone. But in 1595, he took part in an old Irish ceremony to become 'The O'Neill', the Chief of Tír Eoghain. This was a direct challenge to English power.

Hugh grew up in an Anglo-Irish family, the Hovendans, near Dublin. Living in an English-controlled area, he learned about English customs and politics. He even attended the Irish Parliament and the English court. He made friends with powerful English nobles like the Earls of Ormonde and Leicester.

After Shane O'Neill died in 1567, Hugh returned to Ulster. He was protected by Sir Henry Sidney, the English Lord Deputy of Ireland. In Tír Eoghain, Hugh's cousin, Turlough Luineach O'Neill, had become The O'Neill. However, the English did not recognize Turlough as the rightful Earl of Tyrone. So, the English Crown supported Hugh O'Neill as their ally in Gaelic-controlled Ulster.

During the Second Desmond Rebellion in Munster in 1580, Hugh fought with the English against Gerald FitzGerald, 14th Earl of Desmond. He also helped Sir John Perrot against Sorley Boy MacDonnell in 1584. An English commander even said Hugh was the "first Irish lord to spill blood" for the English.

Rising to Power

In 1586, Hugh was called to the Irish House of Lords in Dublin as the Earl of Tyrone. After visiting the English court, he was given the official rights to his grandfather Conn O'Neill's lands.

Turlough Luineach O'Neill, the current 'The O'Neill', had not yet chosen his successor (called a tanist). Hugh and Shane's sons, known as the MacShanes, were both hoping for the position. The MacShanes were popular within Tyrone because of their father. However, other smaller kingdoms disliked them because Shane had been cruel. Also, the MacShanes lost a key ally when the Fitzgeralds of Desmond were defeated in the Desmond Wars.

Hugh married into the family of Red Hugh O'Donnell of Tír Chonaill. This marriage gave him an important ally. With O'Donnell's help, Hugh got Scottish soldiers to fight the MacShanes. In return, Hugh helped O'Donnell in a dispute over leadership in his own kingdom.

Hugh also had support from powerful English lords and even bribed the Lord Deputy of Ireland Fitzwilliam. With all this support, Turlough was forced to name Hugh as his tanist in 1592. After this, Hugh killed Hugh Gavelagh McShane, one of Shane's sons.

English Suspicions and Escapes

The English government started to worry about O'Neill's growing power. In 1587, they captured Hugh's ally, Red Hugh O'Donnell, and held him in Dublin Castle. Art MacShane O'Neill was also held there. After several failed attempts, O'Neill finally helped O'Donnell and MacShane escape in the winter of 1591. He might have bribed high-ranking officials in Dublin to do this.

The two escaped to the Wicklow Mountains, a safe place for the O'Byrnes, who were allies of O'Neill. An O'Byrne search party found them buried in snow, almost dead, near Glendalough. Red Hugh famously lost his two big toes from frostbite. MacShane died, likely from the cold. Some people wondered if O'Neill had the O'Byrnes kill MacShane to remove him as a rival.

The English often encouraged disputes between Hugh and Turlough to weaken the O'Neills. But the two leaders eventually reached an agreement, and Turlough stepped down in 1593. Hugh was then officially made 'The O'Neill' at Tullyhogue, following the old traditions of Gaelic kings. He became the most powerful lord in Ulster. Turlough died in 1595.

Hugh O'Neill's Career and Power

Hugh O'Neill's time as a leader was full of power struggles. Sometimes he seemed to obey English rule, and other times he secretly worked against the Dublin government with other Irish chiefs. He often bribed officials in Ireland and at Queen Elizabeth I's court in London. Even though the English supported him early on, he seemed unsure if he should ally with them or rebel against their growing control in Ulster.

O'Neill ruled like a very strong leader. When he became 'The O'Neill', he decided to collect more money from his people. He eventually made about £80,000 a year. To compare, the English monarchy in the 1540s only made £40,000. This shows O'Neill had enough money to challenge the English government.

He also made peasants stay on their land, almost like serfs. This helped him produce more goods and ensured he had enough workers. With more money, he bought muskets, pikes, and ammunition from Britain. He even paid Spanish and English military experts to advise him.

Like Shane O'Neill before him, Hugh made all men in his territory join the army, no matter their social class. With more money and workers, O'Neill could arm and feed over 8,000 men. This was very impressive for an Irish Gaelic lord. His army was trained with the newest European weapons and fighting methods.

The Nine Years' War Begins

In the early 1590s, the English government set up a new system in Ulster, led by Henry Bagenal. In 1591, O'Neill angered Bagenal by marrying his sister, Mabel, without his permission. But O'Neill still showed loyalty to the Crown by helping Bagenal defeat Hugh Maguire in 1593. After Mabel died, O'Neill slowly started to openly oppose the English Crown. He sought help from Spain and Scotland.

In 1595, Sir John Norris was sent to Ireland with a large army to defeat O'Neill. But O'Neill captured the Blackwater Fort before Norris was ready. O'Neill was immediately declared a traitor. The war that followed is known as the Nine Years' War.

The Nine Years' War

Hugh O'Neill armed his own clan members instead of relying on Scottish hired soldiers. This allowed him to build a strong army with guns and gunpowder from Spain and Scotland. In 1595, he surprised the English by defeating a small English army at the Battle of Clontibret. He and other Irish chiefs then offered the crown of Ireland to King Philip II of Spain, but Philip refused.

Even though his people and the O'Donnell clan were traditional enemies, O'Neill allied with Hugh Roe O'Donnell. They both wrote to King Philip II of Spain. In their letters, which the English intercepted, they said they were fighting for the Roman Catholic Church and for freedom for the Irish people. In April 1596, Spain promised help. O'Neill then pretended to be loyal to the English whenever it suited him. This plan worked, and he managed to keep the English out of his territory for over two years.

In 1598, a ceasefire was agreed, and Queen Elizabeth officially pardoned O'Neill. But within two months, he was fighting again. On August 14, he destroyed an English army at the Battle of the Yellow Ford on the Blackwater river. The English commander, Henry Bagenal, was killed. This was the biggest defeat for the English in Ireland. If O'Neill had pushed his advantage, he might have overthrown English power. But he waited too long, and the chance was lost.

Essex's Campaign and Spanish Aid

Eight months after the Battle of the Yellow Ford, a new English commander, the Earl of Essex, arrived in Ireland. He brought 16,000 soldiers and 1,500 horses. After months of poorly managed operations, Essex met with O'Neill on September 7, 1599, and agreed to a truce. Queen Elizabeth was very unhappy with the good terms given to O'Neill. Essex then returned to England without permission, which led to his execution for high treason in 1601.

The Queen was in a difficult spot. The question of who would be the next ruler was important, and her best military leaders were struggling against O'Neill. Tyrone continued to work with Irish clans in Munster. He issued a statement to the Catholics of Ireland, asking them to join him and saying that religion was his main concern. After a campaign in Munster in January 1600, where English settlements were destroyed, he went north to Donegal. There, he received supplies from Spain and encouragement from Pope Clement VIII.

In May 1600, the English gained an advantage. Sir Henry Docwra set up an army behind O'Neill in Derry. Meanwhile, the new English commander, Sir Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy, marched from Westmeath to Newry. This forced O'Neill to retreat to Armagh. A large reward was offered for O'Neill, dead or alive.

The Battle of Kinsale

In October 1601, the long-awaited help from Spain arrived. A Spanish army led by Don Juan de Aguila took over the town of Kinsale in the far south of Ireland. Mountjoy quickly moved to stop the Spanish. O'Neill and O'Donnell had to march their armies separately from the north, through areas controlled by Sir George Carew, in the middle of a harsh winter. They received little support along the way.

At Bandon, they joined forces and surrounded the English army that was attacking the Spanish. The English were in a bad state, with many soldiers sick, and the winter made camp life very hard. But due to poor communication with the Spanish and a key failure to stop a brave English cavalry charge, O'Neill's army quickly broke apart. The Irish clans retreated, and the Spanish commander surrendered. The defeat at the battle of Kinsale was a disaster for O'Neill and ended his chances of winning the war.

O'Donnell went to Spain to ask for more help, but he died soon after. With his army shattered, O'Neill went back north. He again pretended to seek a pardon while still defending his land. English forces destroyed crops and animals in Ulster in 1601–1602, especially in the lands of Donal O'Cahan, one of O'Neill's main allies. This caused O'Cahan to leave O'Neill, which greatly weakened his power. In June 1602, O'Neill destroyed his capital at Dungannon and hid in the woods. In early 1603, Queen Elizabeth told Mountjoy to talk with the Irish chiefs. O'Neill surrendered in April to Mountjoy, who cleverly hid the news of the Queen's death until the talks were finished.

Peace and Exile

O'Neill went with Mountjoy to Dublin, where he learned that King James I was the new ruler. In June, he appeared at the King's court, along with Rory O'Donnell, who had become the O'Donnell chief. English courtiers were very angry that King James welcomed these former rebels so kindly.

Hugh O'Neill was allowed to keep his title and most of his lands. But when he returned to Ireland, he immediately argued with the English government in Dublin. Under the 1603 peace agreement, much of his land had been given to his former tenants, who now had new legal rights. O'Neill expected them to support him as before, but they refused. This dispute, especially over Donal O'Cahan's rights, led to O'Neill leaving Ireland.

The Flight of the Earls

"The Flight of the Earls" happened on September 14, 1607. O'Neill and O'Donnell secretly left Rathmullan on Lough Swilly at midnight, sailing for Spain. They brought their wives, families, and servants, a total of ninety-nine people. Bad winds pushed them east, and they ended up in France. The Spanish told them to spend the winter in the Spanish Netherlands instead of coming directly to Spain. In April 1608, they went to Rome, where Pope Paul V welcomed them warmly. Their journey was written down in detail by Tadhg Ó Cianáin. In November 1607, King James I declared their flight an act of treason.

The Earls hoped for military help from Spain. However, Philip III of Spain wanted to keep the peace treaty he had signed with King James I in 1604. Also, Spain's economy had gone bankrupt in 1596, and its navy had been destroyed in 1607. This suggests that the Flight was a sudden, unplanned decision.

Hugh O'Neill died in Rome, Italy, on July 20, 1616. He was buried in the church of San Pietro in Montorio. During his nine years in exile, he constantly planned to return to Ireland. He thought about trying to overthrow English rule or accepting offers of pardon from London. When Sir Cahir O'Doherty started O'Doherty's rebellion by burning Derry in 1608, it gave O'Neill hope, but the rebellion was quickly defeated.

Hugh O'Neill's Influence

In 1598, O'Neill appointed James FitzThomas FitzGerald as the Earl of Desmond. Two years later, he recognized Florence MacCarthy as The MacCarthy Mor, or Prince of Desmond. The failure of Essex's campaign in 1599 created a power gap in most parts of Ireland.

O'Neill had little influence over the English lords in the Pale in Leinster. His army had to take food and supplies by force, which made him unpopular. He also made enemies by interfering with the traditional independence of some lords who did not fully support him. These included Lord Inchiquin, Ulick Burke, 3rd Earl of Clanricarde, the Magennis family, and Tiobóid na Long Bourke.

On November 15, 1599, O'Neill issued a statement to the lords of the Pale, many of whom were Catholic. He claimed his fight was not for personal power but for the freedom of the Catholic religion. This was hard for them to believe, as before 1593, he had practiced as an Anglican and was not known for being very religious.

At an international level, O'Neill and O'Donnell offered themselves as subjects to King Philip II of Spain in late 1595. They even suggested that Archduke Albert could be crowned Prince of Ireland, but this was refused. In late 1599, after Essex's failed campaign, O'Neill was in a strong position. He sent Queen Elizabeth a list of 22 terms for a peace agreement. This showed he accepted English rule over Ireland but hoped for religious tolerance and a strong Irish-led government. His proposal was ignored.

Hugh O'Neill's Family

Hugh O'Neill was married four times:

- He married a daughter of Brian McPhelim O'Neill around 1574. This marriage was later cancelled, but they had several children.

- In 1574, he married Siobhán (or Joanna), daughter of Sir Hugh O'Donnell. They had two sons and three daughters.

- Hugh (1585–1609), known as the Baron of Dungannon. He died in Rome.

- Henry O'Neill (around 1586–1617/1621). He became a colonel in an Irish army regiment.

- Ursula, who was said to have married Sir Nicholas Bagenal.

- Sorcha (or Sarah), who married Arthur Magennis, 1st Viscount Iveagh.

- A daughter who married The 3rd Viscount Mountgarret.

- Mabel Bagenal (died 1595), daughter of Sir Nicholas Bagenal.

- Catherine Magennis (died 1619), daughter of Sir Hugh Magennis. She went with O'Neill when he fled. She had several daughters, including Alice, who married The 1st Earl of Antrim. She also had two sons:

- John O'Neill (died 1641). He called himself the 3rd Earl of Tyrone and fought in the Spanish army.

- Con Brian (died 1617 in Brussels).

It is thought O'Neill married a fifth time while living in Rome. He also had other children. One son, Con, was left behind when O'Neill fled. He was educated in England and died around 1622.

Hugh O'Neill in Culture

- In his 1861 poem Eirinn a' Gul ("Ireland Weeping"), Scottish poet Uilleam Mac Dhunlèibhe remembered stories about the Irish people. He wished for leaders like Red Hugh O'Donnell, Hugh O'Neill, and Hugh Maguire who fought against Queen Elizabeth I.

- Hugh O'Neill was played by Alan Hale Sr. in the 1939 film The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex.

- Tom Adams played Hugh O'Neill (renamed Henry O'Neill) in the 1966 Disney film The Fighting Prince of Donegal.

- In the 1971 BBC drama Elizabeth R, he was played by Patrick O'Connell.

- O'Neill is the main character in Brian Friel's 1989 play Making History. The play focuses on his marriage to Mabel Bagenal.

- Running Beast (2007) is a musical play by Donal O'Kelly and Michael Holohan. It remembers The Flight of the Earls.

- Flint and Mirror, a 2022 novel by John Crowley, shows O'Neill as a man with divided loyalties.

Images for kids

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |