Jacquetta Hawkes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacquetta Hawkes

|

|

|---|---|

Hawkes (left) and J. B. Priestley in 1960

|

|

| Born | 5 August 1910 Cambridge, England |

| Died | 18 March 1996 (aged 85) |

| Occupation | Writer and archaeologist |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge |

| Spouses |

Christopher Hawkes

(m. 1933–1953) |

Jacquetta Hawkes (born 5 August 1910 – died 18 March 1996) was an English archaeologist and writer. An archaeologist studies human history by digging up old things. Jacquetta was the first woman to study Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge. She was an expert in prehistoric archaeology, which means she studied very old human history before writing was invented.

She helped dig up Neanderthal remains at an ancient site called Mount Carmel. She also worked for the UK at UNESCO, an organization that promotes peace and understanding through education, science, and culture. She was also in charge of the 'People of Britain' display at the Festival of Britain, a big national exhibition.

Jacquetta Hawkes was well-known for her book A Land (1951). She wrote many books about archaeology, mixing a beautiful writing style with her deep knowledge of landscapes and past human lives. She also used film and radio to share archaeology with more people. In 1953, she married J. B. Priestley, and they wrote several books together. She helped start the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, a group that wanted to stop the use of nuclear weapons. In 1967, she wrote Dawn of the Gods, a book that looked at the ancient Minoan civilization in a new way. In 1971, the Council for British Archaeology made her their Vice-President because she was so good at promoting archaeology.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Jacquetta Hawkes was born Jessie Jacquetta Hopkins on 5 August 1910 in Cambridge, England. She was the youngest child of Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins, a famous scientist who won the Nobel Prize for his work with chemicals in living things. Her mother was Jessie Ann. Jacquetta had one brother and one sister.

From a young age, Jacquetta was interested in archaeology. When she was nine, she found out her home was built on an old medieval cemetery. She would sneak out at night to dig in her garden!

From 1921 to 1928, she went to the Perse School for Girls. In 1929, she went to the University of Cambridge to study Archaeology and Anthropology. She was the first woman ever to take this new degree course. In her second year, she helped dig at a Roman site near Colchester. There, she met her first husband, Christopher Hawkes, who was also an archaeologist. She graduated from Newnham College with top honors.

Early Career in Archaeology

After graduating in 1932, Jacquetta traveled to Palestine. She joined the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. There, she helped dig at Mount Carmel with other archaeologists. She was in charge of digging up a Neanderthal skeleton, which is a very old human ancestor.

When she returned from Palestine, she married Christopher Hawkes on 7 October 1933. She was 22 years old.

In 1934, she published her first article about ancient times in Europe. The same year, she visited a seven-year-old David Attenborough's "museum" of old rocks and fossils. She even gave him some of her own specimens! In 1935, she hosted a BBC Radio show called "Ancient Britain Out of Doors." She talked about important ideas in archaeology with other experts. In 1937, her only child, Nicholas, was born.

In 1938, Jacquetta's first book, The Archaeology of Jersey, was published. Because her book was so successful, she was chosen to be a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. This is a special honor for people who study old things. In 1939, she went to Ireland to oversee the digging of an ancient burial site called Harristown Passage Tomb.

World War II Contributions

During World War II, Jacquetta and her son moved to Dorset to be safer from the war. Later, she returned to London and started working for the government. At first, she helped move important items from the British Museum to a safe place underground.

In 1941, she began working in a government office that planned for Britain after the war. From 1943 to 1949, she worked for the Ministry of Education. Here, she became the Secretary of the UK National Committee for UNESCO. She was also in charge of the film unit, where she created and produced The Beginning of History. This was one of the first films to show prehistory.

Even while working for the government, she continued to write. She published Prehistoric Britain (1944) with her husband, Christopher Hawkes. She also wrote Early Britain (1945). Prehistoric Britain was a very popular book for students in the 1940s and 1950s.

During the war, she met the poet Walter J. Turner. He passed away in 1946, which made Jacquetta very sad. Inspired by his writing, she published her only book of poems, Symbols and Speculations, in 1948.

One of her big tasks as Secretary for UNESCO was preparing for their first conference in Mexico City in 1947. Her future husband, J. B. Priestley, was one of the UK representatives there. Jacquetta and Priestley fell in love at this conference. Priestley famously said she was "Ice without! Fire within!"

Festival of Britain and A Land

In 1949, Jacquetta left her government job to become a full-time writer. She wanted to share archaeology and art in new ways, like through creative writing and films. In 1950, she became a governor of the British Film Institute. She believed in writing about archaeology with feeling, using what she called the 'archaeological imagination'.

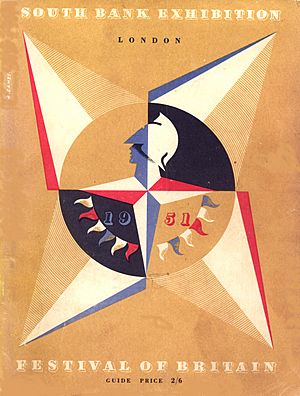

One of her first big projects was being an archaeological advisor for the Festival of Britain in 1951. She created the 'People of Britain' display. This display showed archaeological sites as if they were being discovered for the first time. It went in order from a prehistoric burial to a Bronze Age gold necklace and then a Roman mosaic floor. After the Roman section, visitors saw a recreation of the famous Sutton Hoo ship burial.

Her most famous book, A Land (1951), was published a month after the Festival of Britain opened. In this book, she described the archaeology of Britain and how British identity was shaped by many waves of people moving there over time. The book had drawings by the famous artist Henry Moore. People said it was more like a beautiful story than a scientific report. It became a bestseller in the UK.

In 1952, Jacquetta Hawkes received an OBE, which is an honor from the British government.

Marriage to J. B. Priestley

Jacquetta and Christopher Hawkes divorced in 1953. She then married J. B. Priestley the same year. They lived on the Isle of Wight before moving to Alveston, Warwickshire, in 1960.

Besides being married, they also worked together on several creative writing projects. These included a play called Dragon's Mouth and a book called Journey Down a Rainbow. This book was written as if it were letters between them. Priestley's letters were from a modern America, while Jacquetta's were from the viewpoint of native groups in New Mexico.

Archaeology and Activism

In 1953, Jacquetta wrote the script for a film called Figures in a Landscape. This film was a documentary about the work of the artist Barbara Hepworth. In 1956, she started digging at the Mottistone Estate, which was near her home. She studied a large stone called The Longstone. Her research showed that it was the remains of the entrance to a Neolithic long barrow, which is an ancient burial mound.

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

Jacquetta was very involved in politics. In late 1957 and early 1958, she and Priestley helped start the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). This group officially launched on 17 February 1958. Jacquetta helped organize an important meeting on the Isle of Wight to promote CND. She was also active in the first Aldermaston Marches, which were protests against nuclear weapons. In 1959, she led a march of over 15,000 people to Downing Street and presented a "Ban the Bomb" message. She also started the Women's Committee of CND.

Protecting the Countryside

After Jacquetta and Priestley moved to Alveston, Warwickshire, in the early 1960s, she became the President of the Warwickshire branch of the Campaign to Protect Rural England. This group works to protect England's beautiful countryside. She also became a trustee of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, which looks after the homes connected to William Shakespeare.

Archaeological Work in the 1960s

Jacquetta continued her archaeological research. In 1963, she helped edit UNESCO's book on prehistory called History of Mankind. She wrote the parts about the very old Stone Age (Palaeolithic) and New Stone Age (Neolithic) periods.

In 1968, she published Dawn of the Gods, which looked at the Minoan civilization from ancient Crete. She suggested that it was a 'feminine' society, meaning women might have been the rulers. She used evidence from Minoan art to support her idea. She pointed out that there were no signs of powerful male rulers, which were common in other cultures at that time.

Also in 1968, Jacquetta wrote an article called 'The Proper Study of Mankind'. In it, she argued that archaeology should not focus too much on just science. She believed it should also consider the human side of history. This article caused a lot of discussion among archaeologists.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1971, Jacquetta was chosen as Vice-President of the Council for British Archaeology. This was to honor her many years of important work. In 1980, she published A Quest of Love, a book about her romantic life.

In 1982, she wrote a biography of another famous archaeologist, Mortimer Wheeler.

Priestley passed away in 1982. After his death, Jacquetta moved to Chipping Campden. She continued her interests in archaeology and science, especially studying birds. Her last book, The Shell Guide to British Archaeology, was written with archaeologist Paul Bahn and published in 1986.

Jacquetta Hawkes was known for her striking looks. Many photographers took her picture throughout her life, including Lord Snowdon and Bern Schwartz.

Death and Commemoration

Jacquetta Hawkes died in Cheltenham on 18 March 1996. Her ashes are buried with Priestley's in the churchyard at Hubberholme. A special plaque on the church remembers them.

Even though some archaeologists thought Jacquetta's writing was too "poetic" for science, her work has become popular again in recent years. Her book A Land was re-released in 2012. Jacquetta's artistic and human approach to archaeology has been called "creative archaeology."

Archive and Exhibitions

The University of Bradford holds her archive, which is a collection of her diaries, letters, photographs, and writings.

Several exhibitions have been inspired by Jacquetta Hawkes' life and work:

- Christine Finn: Back to a Land (2012) at Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

- Pots Before Words (2014) at the University of Bradford.

- The Sun Went in, the Fire Went Out (2016) at Chelsea College of Art.

- Isle of Wight: Hidden Heroes (2018) at Carisbrooke Castle.

Selected Works

Books

- Hawkes, Jacquetta. Symbols & Speculations. Cresset Press, 1948.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta. A Land. Cresset Press, 1951.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta, and Sir Leonard Woolley. History of Mankind. Vol. 1. International Commission for a History of the Scientific and Cultural Development of Mankind, 1963.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta. Dawn of the Gods. Chatto & Windus, 1968.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta. Mortimer Wheeler: Adventurer in Archaeology. St Martin's Press, 1982.

Articles

- Hawkes, Jacquetta (1935). "The Place Origin of Windmill Hill Culture". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 1: 127–9.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta (1938). "The Significance of Channelled Ware in Neolithic Western Europe". The Archaeological Journal. 95 (1): 126–173.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta (1941). "Excavation of a Megalithic Tomb at Harristown, Co. Waterford". Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 11 (4): 130–47.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta (1951). "A Quarter Century of Antiquity". Antiquity. 25 (100): 171–3.

- Hawkes, Jacquetta (1968). "The Proper Study of Mankind". Antiquity. 62: 252–66.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jacquetta Hawkes para niños

In Spanish: Jacquetta Hawkes para niños