Jennie Collins facts for kids

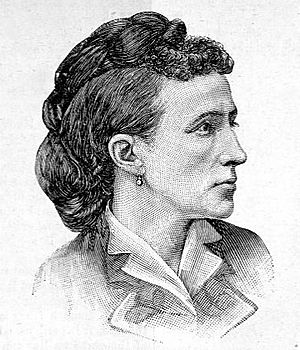

Jennie Collins (1828–1887) was an American woman who worked hard to help others. She was a labor reformer, which means she wanted to make working conditions better for people. She was also a humanitarian, someone who cares about human welfare, and a suffragist, meaning she supported women's right to vote.

Jennie became an orphan when she was young. At 14, she started working in cotton mills to support herself. Later, she worked as a house helper and a seamstress. She was very active in the movement to end slavery and in groups that fought for workers' rights. During the Civil War, she helped in military hospitals. In 1870, Susan B. Anthony, a famous suffragist, asked Jennie to speak at a big meeting in Washington. The next year, Jennie became one of the first working-class women in the U.S. to publish her own book. It was called Nature's Aristocracy; Or, Battles and Wounds in Time of Peace. A Plea for the Oppressed.

Quick facts for kids

Jennie Collins

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Jane Collins

1828 Amoskeag, New Hampshire

|

| Died | July 20, 1887 (aged 59) |

| Resting place | Walnut Hills Cemetery |

| Known for | labor reformer, humanitarian, suffragist |

Contents

Jennie Collins's Early Life

Jennie Collins was born in 1828 in Amoskeag, New Hampshire. This area is now part of Manchester. She grew up in a poor family. When she was a child, both her parents died. Her grandmother, who was a Quaker (a type of Christian), raised her. Sadly, her grandmother also passed away when Jennie was 14 years old.

After her grandmother's death, Jennie had to take care of herself. She worked in cotton mills in places like Lawrence and Lowell. Later, she worked as a domestic helper in Boston. From 1861 to 1870, she made vests for a clothing company. The owners of this company later helped her with her charity work.

While working in Boston, Jennie went to evening classes to learn about history and politics. She even taught a history class herself at a church. Jennie admired Theodore Parker, a Unitarian minister who spoke about important social issues. She was also interested in Spiritualism, a religious movement that often supported workers' and women's rights.

Jennie was strongly against slavery, just like Theodore Parker. During the Civil War, she volunteered in military hospitals. She also taught children of soldiers and organized local women to do charity work for Union soldiers.

How Jennie Fought for Change

While still making vests, Jennie Collins started speaking out about issues important to workers and women. She also campaigned for political leaders she believed in. At one event, she was the only woman speaker. She spoke in favor of Ulysses S. Grant, Charles Sumner, and William Claflin.

Her first big public speech was in 1868. She spoke about women's rights from the point of view of a working-class woman. This was similar to how Margaret Foley would speak years later. In the same year, she spoke at the meeting where the Daughters of St. Crispin was formed. This was the first national women's labor union in the U.S.

Jennie's reputation grew, and she became a leading speaker in Boston. She talked about important topics like stopping child labor, asking for an eight-hour workday, and getting better pay and working conditions for women. In 1869, she joined the National Labor Reform League. She also helped start the Boston Working Women's League.

In 1869, she supported workers who were on strike at the Cocheco Mill in New Hampshire. She spoke to thousands of people in Lowell, asking them to boycott the company. Her powerful speech caught the attention of Susan B. Anthony. Anthony then invited Jennie to speak at the 1870 convention of the National Woman Suffrage Association. Her speech in Washington was a great success. People said she told her stories with such feeling that many in the audience cried.

Boffin's Bower: A Helping Hand

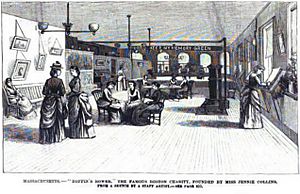

In the summer of 1870, Jennie Collins opened a special place for working women called Boffin's Bower. Business leaders in the area helped her financially. It was located at 813 Washington Street in Boston. The unusual name came from a book by Charles Dickens called Our Mutual Friend.

Jennie explained the name choice: "If I had called my place 'Headquarters for Working Women,' it wouldn't have gotten any attention. But when I put up the sign 'Boffin's Bower,' everyone came to see what it was. I made many friends that way and got a lot of help."

Boffin's Bower started simply with a sitting room and a piano. It grew to include a reading room with books and newspapers. There was also a workshop with sewing machines. The Bower gave food and clothes to women who needed them. It also offered temporary shelter to a few homeless women.

Jennie used her connections with local businesses to help hundreds of women find jobs each year. She even helped the first female employees get jobs at the Boston Post Office. For special occasions, she arranged entertainment. There were Christmas dinners, funny readings, music, and talks by local speakers like Julia Ward Howe.

Jennie knew that charity alone couldn't fix the main reasons for poverty. She always tried to do more. At one point, she planned to open a "kitchen school." In 1871, she asked the state government for help to start a Young Woman's Apprentice Association. This group would train unskilled workers for jobs.

Through the Working Women's League, Jennie and Aurora Phelps tried to create a community for women called "Aurora." It would be a place where women could build their own homes in rural Massachusetts. However, they couldn't raise enough money for this project.

Meanwhile, Jennie had to focus on the immediate needs of the women at Boffin's Bower. In 1872, the Great Boston Fire destroyed a large part of downtown Boston. Hundreds of women lost their jobs and homes. They came to the Bower for help.

To raise money for Boffin's Bower, Jennie gave paid lectures and organized a yearly fair. She also gave most of the money from her book, Nature's Aristocracy, which was published in 1871. The book was a collection of her life stories, strong opinions, and short fictional tales. It argued that American society had moved away from its founding ideals. Jennie believed this created unfair wealth differences.

Even though she didn't have much formal education, Jennie dreamed of a writing career. Her yearly reports about Boffin's Bower were widely read. Newspapers across the country reported on them. These reports highlighted the needs of "the accidental poor." These were people who worked hard but couldn't support themselves when sick or old. They often couldn't get help from charities because they weren't seen as "beggars."

Jennie wrote powerfully about working mothers who couldn't find affordable childcare. She also wrote about women who were paid very little and girls who were cheated out of their wages. In 1874, the State Bureau of Labor Statistics asked for her input for a report on working women in Boston.

Jennie Collins never married. People who knew her described her as strong-willed and smart, but also kind. A reporter once wrote that she was "the champion and voice of the working-women of New England."

Jennie's Later Years and Legacy

Jennie Collins suffered from asthma, but she stayed active until the end of her life. She wrote many articles for newspapers and journals. She also published yearly reports for Boffin's Bower. In her last years, she lived with a widowed friend and her friend's brother.

Jennie died in 1887 from consumption (an old name for tuberculosis) in Brookline, Massachusetts. Her gravestone at Walnut Hills Cemetery reads, "Jennie Collins, the Working-Girl's Friend, and Founder of 'Boffin's Bower.' Died July 20, 1887, aged 59 Years."

Boffin's Bower was created almost 20 years before South End House, which is often called Boston's first settlement house. While Boffin's Bower offered many similar services, it was run by a working-class woman who understood the problems of the poor firsthand. After Jennie's death, a charity called the Helping Hand Society continued her work. They opened a low-rent rooming house for working girls.

A new edition of Jennie's book, Nature's Aristocracy, was published in 2010. A historian named Judith Ranta said it was "the first attempt by a U.S. author of any background or gender to produce an extended overview of working-class life."

Jennie Collins and Boffin's Bower are remembered on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail.

Writings

See also

In Spanish: Jennie Collins para niños

In Spanish: Jennie Collins para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |