Jewish question facts for kids

The Jewish question was a big discussion in Europe during the 1800s and 1900s. It was about how Jewish people should be treated and what their place in society should be. This debate was similar to other "national questions" that dealt with the rights and status of minority groups.

The discussion started when Jewish people began gaining more rights in Western and Central Europe. This happened after the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Key topics included the challenges Jewish people faced, like limits on their jobs or where they could live. It also covered ideas like Jewish people becoming more like the general population or developing their own culture.

Sadly, from the 1880s, the term was used by groups who hated Jewish people (called antisemitic movements). It reached its worst point with the Nazi phrase "Final Solution to the Jewish Question." This led to the terrible events of the Holocaust. The term was also used by people who supported or opposed creating an independent Jewish homeland.

Contents

What Was the Jewish Question?

The phrase "Jewish question" first appeared in Great Britain around 1750. It was used during debates about a law that would allow Jewish people to become citizens. At first, the term was neutral. It simply described the unique situation of Jewish people as a group, especially as new nations were forming. Historians say that many "solutions" were suggested to this "Jewish question." These ideas aimed to deal with the challenges Jewish people faced or were seen to pose.

The discussion then moved to France after its revolution in 1789. In Germany, it was debated in 1843 through a book by Bruno Bauer called Die Judenfrage ("The Jewish Question"). Bauer believed that Jewish people could only gain full political rights if they gave up their religious identity. He thought a country should be secular, meaning it doesn't favor any religion.

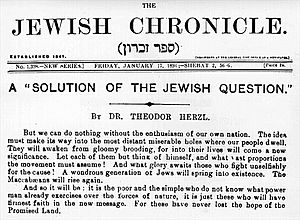

Later, in 1896, Theodor Herzl wrote a book called Der Judenstaat. He suggested Zionism, which is the idea of creating an independent Jewish state. He thought this state, ideally in Ottoman-controlled Palestine, would be a modern "solution" to the Jewish question.

In the 1800s, hundreds of writings discussed this topic. Many suggested solutions like moving Jewish people, sending them away, or having them blend into society. Others argued for Jewish people to be fully included and educated. This debate also questioned whether the "problem" was caused by Jewish people or by those who opposed them.

Around 1860, the term "Jewish question" started to be used in a very negative, antisemitic way. Jewish people were described as a problem for German identity and unity. People who hated Jewish people, like Wilhelm Marr and Houston Stewart Chamberlain, said that integration was impossible. They demanded that Jewish people be removed from important areas like the press, education, and government. They also opposed marriages between Jewish and non-Jewish people.

Even some Jewish writers explored the topic. For example, Martin Salomonski's 1934 science fiction book imagined a safe place for Jewish people on the moon.

The most terrible use of this phrase was by the Nazis in the 1900s. They called their plan to kill all Jewish people in Europe the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question." This horrific event is known as the Holocaust.

Bruno Bauer's View on the Jewish Question

In his 1843 book, Bruno Bauer argued that Jewish people could only achieve full political rights if they let go of their specific religious beliefs. He thought that a country should be secular, meaning it doesn't mix with religion. Bauer believed that a secular state had no room for social identities based on religion. He felt that religious demands were not compatible with the idea of "Rights of Man." For Bauer, true political freedom meant getting rid of religion's influence in public life.

Karl Marx's Response

Karl Marx disagreed with Bauer in his 1844 essay, On the Jewish Question. Marx argued that Bauer was wrong to say that Jewish religion stopped Jewish people from fitting in. Instead, Marx questioned Bauer's whole idea of political freedom itself.

Marx used Bauer's essay to share his own thoughts on liberal rights. He pointed out that Bauer was mistaken in thinking that religion would disappear in a secular state. Marx gave the example of the United States, which had no official state religion but where religion was still very common. Marx believed that a "secular state" didn't oppose religion but actually allowed it to exist. Removing religious requirements for citizenship didn't get rid of religion. Instead, it made people think of individuals separately from their religion or wealth. This led Marx to his main point: even if people were "politically" free in a secular state, they were still limited by economic unfairness. This idea later became a key part of his criticisms of capitalism.

After Marx's Ideas

The debate continued into the 1900s. The Dreyfus Affair in France, which showed strong antisemitism, made the issue even more important. Some leaders still favored Jewish people blending into European society. Others, like Theodor Herzl, pushed for a separate Jewish state and the Zionist movement.

In 1917, Josef Ringo also suggested creating a Jewish state in his book, The Jewish question in its historical context and proposals for its solution.

Between 1880 and 1920, millions of Jewish people found their own solution to the pogroms (violent attacks) in Eastern Europe. They moved to other places, mostly the United States and Western Europe.

The Nazi "Final Solution"

In Nazi Germany, the term Jewish Question (Judenfrage in German) meant the belief that Jewish people living in Germany were a problem for the country. In 1933, two Nazi thinkers suggested that the "Jewish Question" could be solved by moving Jewish people to Madagascar, or somewhere else in Africa or South America. They also discussed whether to support German Zionists. One of them, Johann von Leers, even claimed that creating a Jewish homeland in Mandatory Palestine would cause problems.

When Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party came to power in 1933, they started making harsh laws. These laws aimed to separate Jewish people and eventually remove them from Germany and all of Europe. The next step was to persecute Jewish people and take away their citizenship with the 1935 Nuremberg Laws. Starting with the 1938 Kristallnacht (a violent attack on Jewish people and their property), and later during World War II, Jewish people were sent to concentration camps. Finally, the government carried out the planned killing of Jewish people, known as the Final Solution to the Jewish Question or the Holocaust.

The Nazis used propaganda to control public opinion. This included ideas from books that promoted false science about human heredity and race. The book Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Living also played a role. In occupied France, the government that worked with the Nazis created an "Institute for studying the Jewish Questions."

In the United States

The "Jewish problem" was also discussed in other countries with mostly European populations, even while the Holocaust was happening. For example, American military officer Charles Lindbergh used this phrase in his speeches and writings.

Today's Use of the Term

Today, a common antisemitic conspiracy theory is the false belief that Jewish people have too much power in media, banking, and politics. Based on this harmful idea, some groups and activists still discuss the "Jewish Question." They offer different ideas to "solve" it. In the early 2000s, white nationalists, alt-right groups, and neo-Nazis use the short form JQ to refer to the Jewish question.

See also

- Antisemitic canard

- Armenian question

- David Nirenberg § Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition

- German Question

- Irish question

- Martin Luther and antisemitism

- National question

- Negro Question

- Polish question

- The Race Question

- Ulrich Fleischhauer

- Useful Jew

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |