John Frankenheimer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

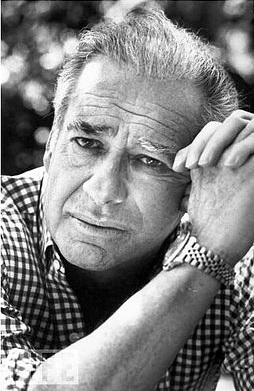

John Frankenheimer

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

John Michael Frankenheimer

February 19, 1930 Queens, New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | July 6, 2002 (aged 72) Los Angeles, California, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Williams College |

| Occupation | Film director |

| Years active | 1948–2002 |

| Spouse(s) | Joanne Frankenheimer (divorced) Carolyn Miller

(m. 1954; div. 1962)Evans Evans

(m. 1963) |

| Children | 2 |

John Michael Frankenheimer (born February 19, 1930 – died July 6, 2002) was a famous American director. He made many movies and TV shows. He was known for his exciting action and suspense films, as well as dramas that explored social issues.

Some of his well-known movies include Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), The Manchurian Candidate (1962), and Ronin (1998). He also directed Grand Prix (1966), which was famous for its thrilling car races.

Frankenheimer won four Emmy Awards for directing TV movies in the 1990s. These included Against the Wall, The Burning Season, Andersonville, and George Wallace. The movie George Wallace also won a Golden Globe Award.

His films and TV shows were important because they made people think. He helped create the "modern-day political thriller" genre. This happened during the Cold War, a time of tension between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Frankenheimer was very skilled with cameras and special effects. He often created stories where his main characters faced difficult choices. He also showed how the environment around them affected their lives.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Frankenheimer was born in Queens, New York City. His mother was Irish Catholic, and his father was of German Jewish descent. John was raised in his mother's religion. He was the oldest of three children.

From a young age, John loved movies. He remembered going to the cinema every weekend. When he was about seven or eight, he watched a very long, 25-episode movie marathon of The Lone Ranger.

In 1947, he finished school at La Salle Military Academy. In 1951, he graduated from Williams College with a degree in English. He was the captain of the tennis team and thought about becoming a professional tennis player.

However, he decided to focus on acting instead. He acted in college and in summer plays for a year. He later said he wasn't a very good actor because he was shy.

Air Force Film Squadron: 1951-1953

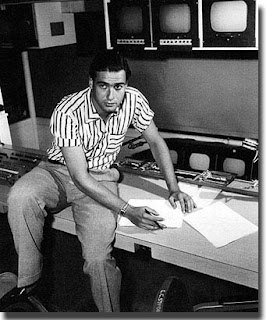

After college, Frankenheimer joined the Air Force. He was first assigned to a mailroom in Washington, D.C. But he quickly moved to an Air Force film squadron in Burbank, California. This is where he started to seriously think about directing films.

He had a lot of freedom in the Air Force photography unit. He could set up lights, operate cameras, and edit films he created himself. His first film was a documentary about an asphalt factory.

He also worked extra jobs, making TV commercials for a cattle breeder. He learned a lot about filmmaking during this time. He also read books about film techniques, including those by the famous Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein. Frankenheimer left the military in 1953.

Television's "Golden Age": 1953-1960

After leaving the military, Frankenheimer wanted to work in film in California. When that didn't happen, he moved back to New York. He found a job at Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) in 1953. He started as a director of photography for The Garry Moore Show.

He then became an assistant director for other shows like You Are There and Danger. In late 1954, he became a director for these shows. His first directing job was for an episode called "The Plot Against King Solomon" (1954), which was a success.

Throughout the 1950s, he directed over 140 episodes for popular shows like Playhouse 90 and Climax!. He directed adaptations of famous writers like Shakespeare and Ernest Hemingway. Many famous actors like Ingrid Bergman and Jack Lemmon starred in these live TV shows. Frankenheimer is considered a very important director from the "Golden Age of Television". This was a time when live TV dramas were very popular and new.

Film Career

Frankenheimer's first movies looked at social issues like youth crime. These films included The Young Stranger (1957), The Young Savages (1961), and All Fall Down (1962).

His 1962 political thriller The Manchurian Candidate is often seen as his most important film. It made a huge impact and showed that John Frankenheimer was a major director. The movie is about brainwashing and a secret plot.

Frank Sinatra starred in the film, along with Laurence Harvey and Angela Lansbury. Angela Lansbury was even nominated for an Academy Award for her role.

In 1964, Frankenheimer directed Seven Days in May. This movie was based on a popular novel. It tells the story of a possible military takeover in the United States in the future. The film was praised for its great acting and was popular with audiences.

Frankenheimer was tired after Seven Days in May. He didn't plan to direct The Train (1964). This movie is about the French Resistance trying to stop a train full of valuable art from being taken by the Nazis during World War II. The film is known for its realistic style and exciting action scenes.

He used special camera techniques to make the train action look very real. He even used a special "hydrogen cannon" to make car crashes look authentic. The Train was a commercial success and won an Academy Award nomination for its screenplay.

Seconds (1966) is a strange and unsettling film. It's about a man who is unhappy with his life and undergoes a secret surgery to change his body and identity. But his new life doesn't turn out as he hoped. The film was not well-received at first, but it later gained a cult following.

By the mid-1960s, Frankenheimer was one of Hollywood's top directors. He directed Grand Prix (1966), his first color film, which was shot in a special 70mm format. Frankenheimer loved car racing, so he was very excited about this project.

The movie is about the lives of Formula One race car drivers. Frankenheimer used innovative camera techniques, like mounting cameras directly onto the race cars. This gave viewers a thrilling, realistic view from inside the race. He also used split-screens to show different things at once.

Grand Prix was a commercial success. It won three Academy Awards for Best Sound Effects, Best Editing, and Best Sound Recording.

The Extraordinary Seaman (1969) was a comedy, which was different from his usual serious films. It was set during World War II.

Frankenheimer also directed The Fixer (1968), based on a famous novel. The film was praised for its strong performances from actors like Alan Bates. Frankenheimer was very proud of this movie.

He then directed The Horsemen (1971) in Afghanistan, starring Jack Palance and Omar Sharif. It was about a father and son who play the Afghan sport of buzkashi (a type of horse polo).

Because he spoke fluent French, Frankenheimer directed French Connection II (1975), which was set in Marseille, France. It was a successful sequel. He then directed Black Sunday (1977), a thriller filmed at a real Super Bowl X game.

In the 1980s, many of his films were not as successful. However, Frankenheimer made a strong comeback in the 1990s by returning to TV. He directed two films for HBO in 1994, Against the Wall and The Burning Season. These won him several awards and brought him new praise. He also directed Andersonville (1996) and George Wallace (1997) for Turner Network Television, which were highly praised.

His 1996 film The Island of Doctor Moreau had many problems during filming and received bad reviews. Frankenheimer later said he had a terrible time making it.

However, his next film, Ronin (1998), was a big success. It starred Robert De Niro and was known for its amazing car chases and spy plot. It was popular with both critics and audiences. He even had a small acting role in The General's Daughter (1999).

Last Years and Death

Frankenheimer's last movie for theaters was Reindeer Games (2000). In 2001, he directed a short action film called Ambush for BMW. His final film was Path to War (2002) for HBO. This movie looked back at the Vietnam War and was nominated for many awards.

John Frankenheimer passed away suddenly on July 6, 2002, in Los Angeles, California. He was 72 years old and died from a stroke after spinal surgery.

Archive

John Frankenheimer's collection of films and videos is kept at the Academy Film Archive.

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1957 | The Young Stranger | |

| 1961 | The Young Savages | |

| 1962 | All Fall Down | Nominated- Palme d'Or |

| Birdman of Alcatraz | Nominated- DGA Award for Outstanding Directing – Feature Film | |

| The Manchurian Candidate | Also producer Nominated- Golden Globe Award for Best Director Nominated- DGA Award for Outstanding Directing – Feature Film |

|

| 1964 | Seven Days in May | Nominated- Golden Globe Award for Best Director |

| The Train | Replaced Arthur Penn | |

| 1966 | Seconds | Nominated- Palme d'Or |

| Grand Prix | Nominated- DGA Award for Outstanding Directing – Feature Film | |

| 1968 | The Fixer | |

| 1969 | The Extraordinary Seaman | |

| The Gypsy Moths | ||

| 1970 | I Walk the Line | |

| 1971 | The Horsemen | |

| 1973 | The Iceman Cometh | |

| Impossible Object | ||

| 1974 | 99 and 44/100% Dead | |

| 1975 | French Connection II | |

| 1977 | Black Sunday | |

| 1979 | Prophecy | |

| 1982 | The Challenge | |

| 1985 | The Holcroft Covenant | |

| 1986 | 52 Pick-Up | |

| 1989 | Dead Bang | |

| 1990 | The Fourth War | |

| 1991 | Year of the Gun | Nominated- Deauville Critics Award for Best Feature Film |

| 1996 | The Island of Dr. Moreau | Replaced Richard Stanley |

| 1998 | Ronin | |

| 2000 | Reindeer Games | |

| 2001 | Ambush | Short film |

Television

TV series

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1954 | You Are There | Episode: "The Plot Against King Solomon" |

| 1954-55 | Danger | 6 episodes |

| 1955-56 | Climax! | 26 episodes |

| 1956-60 | Playhouse 90 | 27 episodes |

| 1958 | Studio One in Hollywood | Episode: "The Last Summer" |

| 1959 | DuPont Show of the Month | Episode: "The Browning Vision" |

| Startime | Episode: "The Turn of the Screw" | |

| 1959-60 | NBC Sunday Showcase | 2 episodes |

| 1960 | Buick-Electra Playhouse | 3 episodes |

| 1992 | Tales from the Crypt | Episode: "Maniac at Large" |

TV movies

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1956 | The Ninth Day | |

| 1960 | The Snows of Kilimanjaro | |

| The Fifth Column | ||

| 1982 | The Rainmaker | Nominated- CableACE Award for Best Direction in a Movie or Miniseries |

| 1994 | Against the Wall | Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Directing for a Limited Series or Movie Nominated- CableACE Award for Best Direction in a Movie or Miniseries Nominated- DGA Award for Outstanding Directing – Miniseries or TV Film |

| The Burning Season | Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Directing for a Limited Series or Movie CableACE Award for Best Direction in a Movie or Miniseries Nominated- Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Television Movie Nominated- CableACE Award for Best Movie or Miniseries |

|

| 1996 | Andersonville | Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Directing for a Limited Series or Movie Nominated- Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Television Movie Nominated- DGA Award for Outstanding Directing – Miniseries or TV Film |

| 1997 | George Wallace | Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Directing for a Limited Series or Movie CableACE Award for Best Miniseries CableACE Award for Best Direction in a Movie or Miniseries Nominated- Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Television Movie Nominated- DGA Award for Outstanding Directing – Miniseries or TV Film |

| 2002 | Path to War | Nominated- Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Directing for a Limited Series or Movie Nominated- Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Television Movie Nominated- DGA Award for Outstanding Directing – Miniseries or TV Film |

Awards and Nominations

- 1964 Train nominated for Best Film - Any Source

- 1962 Manchurian Candidate nominated for Best Film - Both Any Source and British

- 1966 Seconds nominated for Competing Film

- 1962 All Fall Down nominated for Competing Film

New York Film Critics Circle Award

- 1968 Fixer nominated for Best Direction

- 1968 Fixer nominated for Best Film

- 1962 Birdman of Alcatraz nominated for Competing Film

- 1962 Birdman of Alcatraz won for San Giorgio Prize

Frankenheimer was also inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 2002.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: John Frankenheimer para niños

In Spanish: John Frankenheimer para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |