John Peckham facts for kids

Quick facts for kids John Peckham |

|

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

Effigy from Peckham's tomb in Canterbury Cathedral

|

|

| Appointed | 25 January 1279 |

| Reign ended | 8 December 1292 |

| Predecessor | Robert Burnell |

| Successor | Robert Winchelsey |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 19 February 1279 by Pope Nicholas III |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1230 Sussex |

| Died | 8 December 1292 Mortlake |

| Buried | Canterbury Cathedral |

| Denomination | Catholic |

John Peckham (born around 1230 – died 8 December 1292) was a Franciscan friar who became the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1279 to 1292.

Peckham studied at the University of Paris and later taught theology there. He was known for his traditional views, which sometimes differed from those of Thomas Aquinas, especially concerning the nature of the soul. Peckham also studied optics (the science of light and vision) and astronomy. His work in these areas was greatly influenced by scholars like Roger Bacon and Alhazen.

Around 1270, Peckham returned to England and taught at the University of Oxford. In 1275, he was chosen as the head of the Franciscans in England. After a short time in Rome, he was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 1279. During his time as archbishop, he worked hard to improve discipline among the clergy and to better manage the church's lands. He also served King Edward I of England in Wales.

As archbishop, Peckham took steps to limit the activities of Jewish communities, such as trying to close down synagogues and discouraging Jewish converts from returning to their original faith. He also spoke out against the practice of lending money with interest (called usury) and criticized Queen Eleanor of Castile for using such loans in ways he believed were unfair to nobles.

John Peckham wrote several books on optics, philosophy, and theology, and also composed hymns. Many copies of his writings still exist today. When he died, he was buried in Canterbury Cathedral, but his heart was given to the Franciscans for burial.

Contents

Early Life and Studies

Peckham came from a modest family, possibly from Patcham in East Sussex. He was born around 1230 and received his early education at Lewes Priory. Around 1250, he joined the Franciscan order in Oxford.

He then moved to the University of Paris, where he studied under Bonaventure. He became an official lecturer in theology. While in Paris, he wrote a book called Commentary on Lamentations.

For many years, Peckham taught in Paris and met many important scholars, including Thomas Aquinas. He famously debated Thomas Aquinas at least twice between 1269 and 1270. In these debates, Peckham defended more traditional religious ideas, while Thomas shared his views on the soul. Peckham's theological ideas later influenced his student Roger Marston, who in turn inspired Duns Scotus.

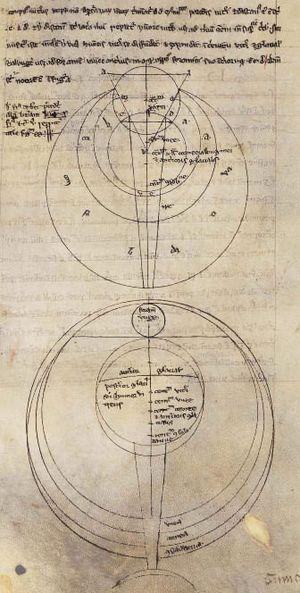

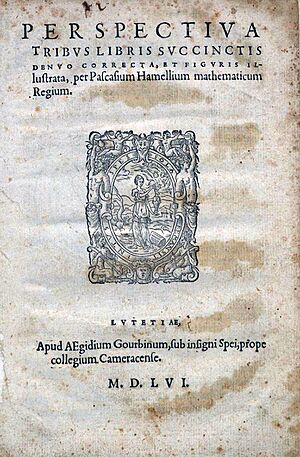

Peckham also explored other subjects. He was guided by the ideas of Robert Grosseteste and Roger Bacon about the importance of experimental science. It's not known exactly where Peckham met Bacon, but it would have been either in Paris or Oxford. Bacon's influence can be seen in Peckham's writings on optics (a book called Perspectiva communis) and astronomy.

In the field of optics, Peckham was influenced by many earlier thinkers, including Euclid, Aristotle, Augustine, al-Kindi, Avicenna, Alhazen, Grosseteste, and Roger Bacon. Historian David Lindberg notes that Alhazen was the most important influence, and Peckham aimed to "follow in the footsteps" of Alhazen's work.

Return to England and Archbishop Role

Around 1270, Peckham returned to England to teach at Oxford. In 1275, he was elected the head of the Franciscans in England. He didn't stay in that role for long, as he was called to Rome to be a theological lecturer at the papal palace. It's likely that he wrote his Expositio super Regulam Fratrum Minorum during this time, a work that included important information on preaching.

In 1279, Pope Nicholas III appointed him Archbishop of Canterbury. The Pope had prevented King Edward I's preferred candidate, Robert Burnell, from being chosen. Peckham was officially appointed on 25 January 1279 and became archbishop on 19 February 1279.

Reforming the Church

Peckham strongly believed in strict discipline, which often led to disagreements with his clergy. His first act as archbishop was to call a council in Reading in July 1279 to bring about church reforms. Peckham ordered that a copy of Magna Carta (a famous English charter of rights) should be displayed in all cathedral and collegiate churches. This upset the king, who saw it as interfering with political matters. Another rule he made was about clergy not living in their assigned church areas. Peckham only allowed exceptions if a cleric needed to go abroad to study.

At the Parliament of Winchester in 1279, the archbishop reached a compromise, and Parliament canceled any council rules that dealt with royal policies or power. The copies of Magna Carta were taken down. One reason the archbishop might have given in was that he owed money to the Riccardi family, an Italian banking family who also served King Edward and the Pope. Peckham was even threatened with excommunication (being excluded from the church) if he didn't repay the loans.

However, Peckham worked hard to reorganize the church's lands and finances. From 1283 to 1285, he conducted an investigation into the income of the archdiocese. He set up new ways to manage the church's properties, dividing them into seven administrative groups. Despite his efforts, Peckham was almost always in debt. As a Franciscan, he didn't own personal property to help with his living costs. He also inherited debts from the previous archbishop and never managed to pay them all off.

Working with the Welsh

Despite his other actions, Peckham generally had a good relationship with King Edward. The king even sent him on a diplomatic mission to Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in Wales. In 1282, Peckham tried to make peace between the Welsh and King Edward. However, since Edward wouldn't change his main demands, the mission was unsuccessful. In the end, Peckham even excommunicated some of the Welsh who were fighting against Edward.

While serving King Edward, Peckham formed a low opinion of the Welsh people and their laws. Peckham visited Welsh dioceses as part of his tour of all the areas under his authority. During his visit, Peckham criticized the Welsh clergy for their extravagant spending and heavy drinking. He also found many Welsh clergy to be uneducated, although he did order a Welsh-speaking assistant bishop to be appointed to help with church duties in the diocese of Coventry and Lichfield. Peckham also criticized the Welsh people as a whole, comparing their animal-herding economy to England's farming-based economy, and finding the Welsh to be lazy.

As part of his diplomatic duties, Peckham wrote to Llywelyn. In these letters, the archbishop continued to criticize the Welsh people, this time saying their laws went against both the Old and New Testaments. Peckham was particularly bothered that Welsh laws allowed people involved in murders or other crimes to settle their differences, instead of following English law which punished criminals.

Peckham also had problems with his subordinate, Thomas Bek, who was the Bishop of St David's in Wales. Bek tried to make St David's independent from Canterbury and elevate it to a higher status. This idea had been proposed before, around 1200, but had been stopped. Bek's attempt didn't last long, as Peckham quickly defeated his efforts.

Church Matters and Reforms

Disagreements with King Edward continued over church privileges, royal power, Peckham's use of excommunication, and church taxes. However, in October 1286, Edward issued a legal document called Circumspecte Agatis. This document clearly stated what kinds of cases the church courts could handle. These included moral issues, marriage disputes, arguments about wills, correcting sins, and cases of slander or physical attacks on clergy.

Peckham was very strict in how he interpreted church law. He believed Welsh laws were illogical and didn't fit with the Bible's teachings. He also ordered that the clerical tonsure (a shaved patch on the head worn by clergy) should not just be on the top of the head, but also include the back of the neck and above the ears. This made it easier to tell clergy apart from ordinary people. To help with this, the archbishop also told clergy not to wear regular clothes, especially military outfits. He also stopped an attempt by the Benedictine order in England to change their monastic rules to allow more time for study and better education for monks. Peckham said these changes went against tradition, but he might also have been worried that these reforms would attract people away from the Franciscans.

At a church council held at Lambeth in 1281, Peckham ordered the clergy to teach their congregations about Christian beliefs at least four times a year. They were to explain the Articles of Faith, the Ten Commandments, the Works of Mercy, the Seven Deadly Sins, the Seven Virtues, and the Sacraments. This command became a church law known as the Lambeth Constitutions. These constitutions, originally in Latin, were important for guiding church teachings throughout the rest of the Middle Ages and were later translated into English in the 15th century.

Peckham also targeted the practice of "Pluralism," where one cleric held two or more church positions. He also aimed to stop clergy from being absent from their duties and to improve discipline in monasteries. His main way of fighting these issues was by frequently visiting the dioceses and religious houses under his authority. This often led to arguments about whether the archbishop had the right to make these visits. However, Peckham was also a papal legate (a representative of the Pope), which made these disputes even more complicated. The many legal cases that resulted from his visitation policy strengthened the archbishop's court. Peckham also argued with Thomas de Cantilupe, Bishop of Hereford, over the right to visit subordinate clergy. This quarrel involved an appeal to Rome in 1281, but Thomas died before the case could be decided. Peckham also ordered that clergy should preach to their congregations at least four times a year.

Peckham often disagreed with the bishops under him, mainly because he tried to reform them. However, Peckham's own attitude also played a part in these problems. He once wrote to Roger de Meyland, the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, saying, "These things need your attention, but you have been absent so long that you seem not to care. We therefore order you, on receipt of this letter, to take up residence in your diocese, so that—even if you are not competent to redress spiritual evils—you may at least minister to the temporal needs of the poor." Historian Richard Southern noted that Peckham's disputes with his bishops were "conducted in an atmosphere of bitterness and perpetual ill-will," partly due to a "fussy streak in Peckham's character." Peckham's conflicts arose because his ideals were those of a Franciscan, while most of his clergy were more focused on everyday and material matters. These tensions between the archbishop and his subordinates were made worse by clashes over church and government authority, as well as King Edward's great need for money.

Policies Regarding Jewish Communities

Like many other senior church leaders of his time, Peckham held strong views regarding the Jewish community. He believed certain practices were harmful to Christians. He pushed for greater separation of Jews from Christians, along with other church leaders of the time. He also wanted to end usury (lending money with interest) and prevent Jewish converts from returning to their original faith.

When he heard that the Jewish community in London was allowed to build a new synagogue, which he believed was "confusing to the Christian religion," Peckham worked to stop it. On 19 August 1282, he ordered Richard Gravesend, Bishop of London, to force the Jews of London to destroy all their synagogues except one within a short time. He claimed that having seven synagogues was "causing problems for the Christian religion and scandal to many." In a second letter, he congratulated the Bishop because the "Jewish faith" was being addressed by the bishop's attention. However, he confirmed that they should be allowed to keep one synagogue.

In 1281, Peckham complained to King Edward that converts to Christianity were returning to their former faith. The following year, he reported 17 Jewish apostates (people who abandon their religion). In 1284, Edward issued an order for 13 of them to be arrested. They sought safety in the Tower of London, and Robert Burnell refused to act, fearing it would harm relations with the Jewish community in London. The 13 individuals seem to have avoided punishment. This situation followed a pattern set by Peckham's superiors; the Pope had been complaining for some time about similar cases.

Peckham also disagreed with Queen Eleanor, telling her that her use of loans from Jewish moneylenders to acquire lands was usury and a serious sin. He warned her servants: "It is said that the illustrious lady queen, whom you serve, is occupying many manors, lands, and other possessions of nobles, and has made them her own property – lands which the Jews have gained with usury from Christians under the protection of the royal court."

In Easter 1285, the senior church leaders of the Province of Canterbury, led by Peckham, presented complaints to Edward. Two of these concerned what they saw as weak restrictions on Jews. They complained about converts returning to Judaism and called for a crackdown on usury. Although usury had been banned since 1275 under the Statute of the Jewry, they believed it was still being practiced. They asked that "the Jews' dishonesty and wrongdoing be strongly opposed." Edward replied that little could be done "because of their evilness." In response, the church leaders expressed their shock and stated that the Crown was allowing Jews to "trap Christians through unfair loan agreements and to acquire the lands of nobles through usury." They advised that Edward was capable of stopping this "wrongdoing" and should "strive to punish all usurers through the threat of horrible punishments."

These concerns were repeated directly to Peckham in a letter from Pope Honorius IV in November 1286. Peckham and other church leaders used this letter as guidance to make further demands against the Jews at the 1287 Synod of Exeter. They again demanded that Jews wear special badges, banned Christians from working for Jews or sharing meals with them, and from using Jewish doctors. Jews were also banned from holding public office or building new synagogues, and were told to stay within their own homes on Good Friday.

Death and Legacy

Many copies of Peckham's writings on philosophy and biblical commentary still exist. Queen Eleanor convinced him to write a scholarly work for her in French, which was later described as "unfortunately rather a dull and uninspired little treatise." His poem Philomena is considered one of the finest poems written in its time.

Peckham died on 8 December 1292 at Mortlake. He was buried in the north transept of Canterbury Cathedral. However, his heart was buried with the Franciscans under the high altar of their London church, Greyfriars, London. His tomb can still be seen today. He founded a college at Wingham, Kent in 1286, which was likely a college of canons serving a church.

Works

Many of his works have survived, and some have been printed at various times:

- Perspectiva communis (a work on optics)

- Collectarium Bibliae

- Registrum epistolarum (a collection of letters)

- Tractatus de paupertate (a work on poverty)

- Divinarum Sententiarum Librorum Biblie

- Summa de esse et essentia

- Quaestiones disputatae

- Quodlibeta

- Tractatus contra Kilwardby

- Expositio super Regulam Fratrum Minorum (a commentary on the Franciscan Rule)

- Tractatus de anima (a work on the soul)

- Tractatus de sphaera (a work on astronomy)

- Canticum pauperis

- De aeternitate mundi

- Defensio fratrum mendicantium (a defense of the mendicant friars)

Peckham is the earliest Archbishop of Canterbury whose official records, known as registers, are kept at Lambeth Palace Library.

See also

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |