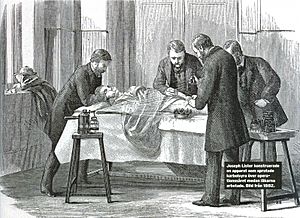

Joseph Lister facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

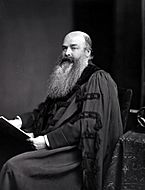

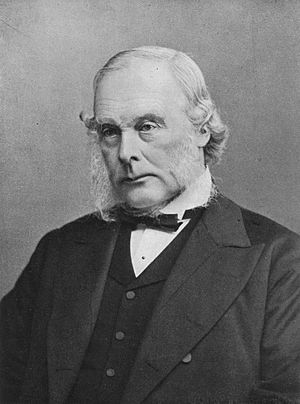

The Lord Lister

|

|

|---|---|

Lister in 1902

|

|

| 37th President of the Royal Society | |

| In office 1895–1900 |

|

| Preceded by | The Lord Kelvin |

| Succeeded by | Sir William Huggins |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 April 1827 Upton House, West Ham, England |

| Died | 10 February 1912 (aged 84) Walmer, Kent, England |

| Resting place | Hampstead Cemetery, London |

| Spouse |

Agnes Syme

(m. 1856; died 1893) |

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

| Education | University College London |

| Known for | Surgical sterile techniques |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine |

| Institutions | |

| Influences | |

| Influenced |

|

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister (1827–1912) was a British surgeon and scientist. He was a pioneer of antiseptic surgery and preventative medicine. Lister completely changed how surgery was done. He is often called the "father of modern surgery."

Lister's work helped reduce post-operative infections. This made surgery much safer for patients. He was not just a great surgeon, but his research into bacteriology and infection in wounds changed surgery worldwide.

Lister's main contributions were:

- He promoted antiseptic surgical care. He used phenol (also called carbolic acid) to sterilise surgical tools, the patient's skin, sutures, and the surgeon's hands.

- He studied how inflammation and tissue blood flow affected wound healing.

- He improved diagnostic science by looking at samples under a microscope.

- He created smart ways to help patients survive surgery.

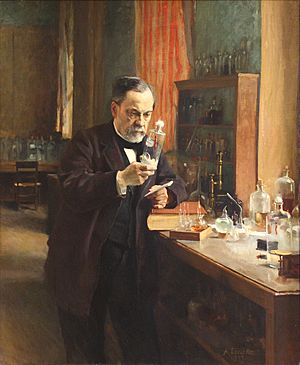

- Most importantly, he connected Louis Pasteur's germ theory (which explained how tiny living things cause fermentation) to how wounds became infected.

Early Life and Family Background

Joseph Lister was born on April 5, 1827. He grew up in a wealthy and educated Quaker family in Upton, England. He was the fourth of seven children born to Joseph Jackson Lister and Isabella Lister. His father was a scientist and wine merchant. His mother, Isabella Harris, worked at a Quaker school.

Joseph's father was famous for improving microscope lenses. He spent 30 years making microscopes better. His work helped make histology (the study of tissues) a real science. Joseph's mother helped her widowed mother at a Quaker school for poor children.

The Lister family moved to Upton House in 1826. This large mansion had 69 acres of land. Joseph's older sister, Mary, later married Rickman Godlee. Their son, also named Rickman Godlee, became a famous neurosurgeon and wrote a book about Lister.

Education and Learning

School Days

As a child, Lister had a stammer. Because of this, he was taught at home until he was eleven. He then went to private Quaker schools in Hitchin and Tottenham. His father made sure he learned French and German.

Lister's father greatly encouraged his interest in natural history. Joseph loved collecting and dissecting small animals and fish. He used his father's microscope to examine them and then drew what he saw. This early interest in science prepared him to become a surgeon and researcher.

University Studies

In 1843, Lister's father sent him to University College London (UCL). This was one of the few universities that accepted Quakers at the time. He started by studying classics and natural philosophy. He won awards in Greek, Latin, and natural philosophy.

In 1846, Lister witnessed a famous operation. Robert Liston performed surgery using ether to put the patient to sleep for the first time. This was a big step for anesthesia.

In 1847, Lister earned his Bachelor of Arts degree. After a period of illness and travel, he began his medical studies in 1849. His main teachers were Thomas Wharton Jones (ophthalmic medicine) and William Sharpey (physiology). Sharpey especially inspired Lister's love for experimental physiology.

Clinical Training

From 1850, Lister began his clinical training at University College Hospital. He worked as an intern and then as a house surgeon for John Eric Erichsen. During this time, Lister became very interested in how wounds heal.

He saw many patients suffer from infections like erysipelas and hospital gangrene. These diseases caused living tissue to rot quickly. Lister noticed that some wounds would heal if they were cleaned. He began to think that something inside the wound itself was causing the problem.

Lister's interest in the germ theory of disease started when he investigated the death of a young boy from pyaemia (blood poisoning). He saw pus in the boy's veins and lungs. He believed this pus had spread from the original infection.

Early Microscope Experiments

While at university, Lister wrote his first scientific papers. These were published in the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science in 1853. He studied the iris of the eye and the muscles in the skin that cause goose bumps. His microscope skills were so good that he corrected observations made by other famous scientists.

His work impressed many, including the naturalist Richard Owen. Lister's accurate drawings, made using a camera lucida, were highly praised.

Graduation and Next Steps

Lister graduated with honors in medicine in 1852. He also became a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. His teacher, Sharpey, advised him to visit James Syme in Edinburgh, a leading surgeon. Sharpey also suggested touring medical schools in Europe.

Scottish universities were known for teaching medicine and surgery scientifically. They were also less expensive and didn't have religious tests, which attracted many bright students. This was different from English medical schools, which often saw surgery as manual labor.

Surgical Career in Edinburgh (1853–1860)

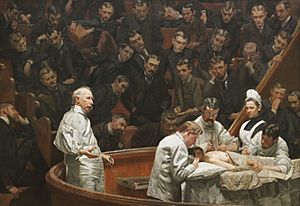

Before Lister's time, many thought infections came from "bad air" or miasma. Hospitals rarely washed hands or wounds. Surgeons often wore dirty gowns as a sign of experience. This led to many infections and deaths.

Working with James Syme

In September 1853, Lister arrived in Edinburgh and met James Syme. Syme was a very skilled and original surgeon. He was known for quick operations, which was important before anesthesia. Syme became a mentor to Lister.

Lister quickly became Syme's assistant at the University of Edinburgh and the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. He helped Syme with every operation and took notes. This was a highly sought-after position.

Marriage and Partnership

Lister fell in love with Syme's daughter, Agnes Syme. His Quaker parents were worried because Agnes was not a Quaker. But Lister was determined. He left the Quakers and became a Protestant.

On April 23, 1856, Joseph and Agnes married. For their honeymoon, they toured medical institutes in Europe. Agnes loved medical research and became Lister's partner in the laboratory for the rest of her life. She was his secretary and they discussed his work as equals. Her careful handwriting filled his notebooks.

Research on Inflammation and Coagulation

Between 1853 and 1859, Lister did many experiments on physiology and pathology. He used his microscope and mostly studied frogs. He also used bats, sheep, cats, and other animals. He was very careful and detailed in his work.

Lister's research focused on inflammation and coagulation (blood clotting). He believed understanding inflammation was key to his antiseptic ideas. He found that when tissue was irritated, blood vessels first contracted, then dilated, and blood flow slowed. He also studied how blood clots formed, which helped understand blood clotting in wounds.

His work showed that capillary action (how blood flows in tiny vessels) is controlled by the arteries. This is affected by injury or irritation. These experiments made his name known beyond Edinburgh.

Moving to Glasgow (1860–1869)

In 1860, Lister became the Professor of Surgery at the University of Glasgow. This was a big step for his career. He moved with Agnes to a new house in Glasgow.

Discovering Pasteur's Germ Theory

In 1865, a chemistry professor named Thomas Anderson introduced Lister to the work of French chemist Louis Pasteur. Pasteur had discovered that tiny living things, called microorganisms, caused fermentation and putrefaction (rotting).

Pasteur's research showed:

- Fermentation and rotting were caused by microbes.

- Microbes were everywhere, even in the air.

- Different microbes caused different types of fermentation.

- Some microbes needed oxygen (aerobic), others didn't (anaerobic).

- Sterile (germ-free) material would not rot.

- The idea of spontaneous generation (life appearing from nothing) was wrong.

Lister realized that if microbes caused rotting, they must also cause infections in wounds. He was one of the few surgeons to immediately accept Pasteur's ideas. This made him think about how to get rid of these microbes on hands, tools, and dressings, and how to clean wounds.

Pasteur suggested three ways to kill microbes: filtering, heating, or using chemicals. Heating and filtering weren't practical for human tissue. So, Lister focused on chemicals.

Using Phenol as an Antiseptic

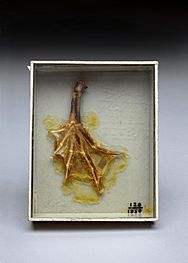

Lister learned about phenol (carbolic acid), which was used to protect wood from rotting. He got a sample and started experimenting with it.

In March 1865, Lister tried using carbolic acid on a patient with a severe broken leg. He cleaned the wound and applied undiluted carbolic acid. This first attempt wasn't fully successful, and the patient died.

Lister then found a purer form of phenol. He created a new dressing using a putty mixed with phenol and linseed oil.

The Antiseptic System

First Success with Antiseptics

On August 12, 1865, Lister had his first success. He used full-strength carbolic acid on an 11-year-old boy, James Greenlees, who had a bad broken leg. Lister applied lint soaked in carbolic acid. After four days, there was no infection. Six weeks later, the boy's bones had healed without any pus. This was amazing at the time.

He later treated another patient, Hainy, with a similar severe leg injury. Hainy also survived, which was rare for such injuries back then.

Lister published his successful results in The Lancet in 1867. He told surgeons to:

- Wear clean gloves.

- Wash their hands with five percent carbolic acid solution before and after operations.

- Wash instruments in the same solution.

- Spray the solution in the operating room.

- Stop using porous materials for instrument handles.

Lister left Glasgow University in 1869 and returned to Edinburgh. He continued to improve his antiseptic methods. His fame grew, and many people came to hear him lecture. As the germ theory of disease became more understood, surgeons realized that preventing bacteria from entering wounds was key. This led to aseptic surgery, which means completely germ-free surgery.

Challenges and Acceptance

Even though Lister was honored later in life, his ideas were criticized at first. Some surgeons didn't believe in airborne microbes. The Lancet medical journal even warned doctors against his ideas in 1873.

However, Lister had supporters, like Marcus Beck, who started using Lister's methods and included them in surgical textbooks. Lister's carbolic acid spray could irritate eyes and lungs, and the bandages sometimes damaged tissue. He eventually stopped using the spray. Because his ideas were new and based on germ theory, it took time for them to be fully accepted.

Later Career in London (1877–1900)

In 1877, Lister moved to London to become a professor at King's College Hospital. He wanted to spread his antiseptic system in the capital city. He brought four assistants from Edinburgh, including Watson Cheyne.

At first, there was resistance from students and staff. His first lecture in London, explaining how microbes caused fermentation, was not well received.

However, Lister continued his work. He performed a groundbreaking operation in 1877, wiring a fractured patella (kneecap) together. This was one of the first times a healthy knee joint was opened in surgery. He also improved mastectomy (breast removal) techniques. He was the first to use catgut for ligatures (tying off blood vessels) and sutures (stitches), and to use rubber drains.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1892, Lister attended a celebration for Louis Pasteur's 70th birthday in Paris. Lister gave a speech, thanking Pasteur for his work. Pasteur famously hugged and kissed Lister, showing their deep respect.

In 1893, Agnes Lister, Joseph's wife, died from pneumonia. This greatly affected Lister, and he became very sad. He retired from Kings College Hospital in 1895.

Despite a stroke, Lister continued to be honored. He became the senior surgeon to Queen Victoria and later to King Edward VII. In 1902, he advised surgeons operating on King Edward VII for appendicitis. The King survived, telling Lister, "I know that if it had not been for you and your work, I wouldn't be sitting here today."

Death and Memorials

Lord Lister died on February 10, 1912, at the age of 84. His funeral was held at Westminster Abbey. He was buried in Hampstead Cemetery in London. Many tributes came from around the world. A marble medallion of Lister is in Westminster Abbey, alongside other famous scientists.

The Lister Memorial Fund was created after his death. It led to the Lister Medal, a very important award for surgeons.

Awards and Honors

Lister received many honors for his achievements:

- He was made a baronet by Queen Victoria in 1883.

- He received the Pour le Mérite, a high Prussian award, in 1885.

- He was made Baron Lister in 1897.

- He became a privy counsellor and one of the first members of the new Order of Merit (OM) in 1902.

- He received the Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog from the King of Denmark in 1902.

He also received many medals, including the Royal Medal (1880) and the Copley Medal (1902). He was elected to the Royal Society in 1860 and served as its president from 1895 to 1900.

Lasting Legacy

- The Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine was named in his honor in 1903.

- The Lister Hospital in Stevenage, England, is named after him.

- His name is on the frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

- Statues of Lister stand in London and Glasgow.

- Mount Lister in Antarctica was named after him.

- Listerine antiseptic mouthwash was named in his honor in 1879.

- The bacterial genus Listeria and the slime mould genus Listerella are named after him.

- He was shown in the 1936 film The Story of Louis Pasteur.

- Postage stamps were issued in 1965 to honor his antiseptic surgery.

Images for kids

-

Lister's hearse before his funeral service at Westminster Abbey

-

Plaque at 12 Park Crescent, Regent's Park, London

See also

In Spanish: Joseph Lister para niños

In Spanish: Joseph Lister para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |