Josquin des Prez facts for kids

Josquin des Prez (born around 1450–1455 – died August 27, 1521) was a very important composer during the Renaissance period. He is sometimes called French or Franco-Flemish. Many people think he was one of the greatest composers of his time. He was a key figure in the Franco-Flemish School of music and greatly influenced music across Europe in the 1500s.

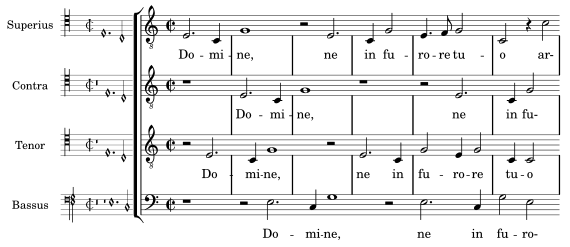

Josquin built on the ideas of earlier composers like Guillaume Du Fay and Johannes Ockeghem. He created a complex style where different voices in his music would imitate each other. This is called polyphony. He also made sure the music really matched the words, using shorter, repeated musical ideas (called motifs). Josquin was a singer, and most of his music is for voices. This includes masses (music for church services), motets (sacred songs), and secular chansons (French songs).

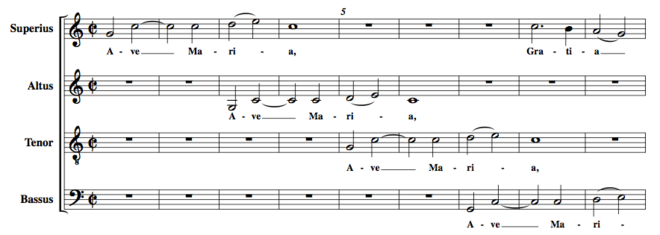

Not everything about Josquin's life is known for sure. He was born in a French-speaking part of Flanders. He might have been a choirboy and studied with Ockeghem. By 1477, he was singing for René of Anjou and then probably for Louis XI of France. Josquin became quite wealthy. In the 1480s, he traveled to Italy with Cardinal Ascanio Sforza. He might have even worked for King Matthias Corvinus in Hungary. During this time, he wrote famous pieces like the motet Ave Maria ... Virgo serena and popular chansons like Adieu mes amours.

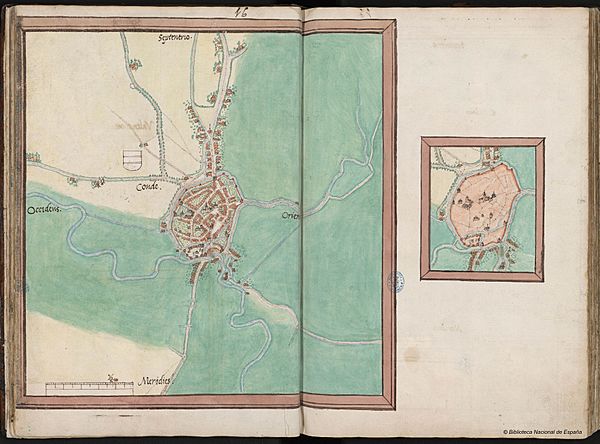

He worked for several important leaders, including Pope Innocent VIII and Pope Alexander VI in Rome, Louis XII in France, and Ercole I d'Este in Ferrara. Many of his works were printed by Ottaviano Petrucci in the early 1500s. In his last years in Condé, Josquin wrote some of his most loved works. These include the masses Missa de Beata Virgine and Missa Pange lingua. He also wrote motets like Benedicta es and chansons like Mille regretz.

Josquin was very influential during his life and even after he died. He is known as the first Western composer whose fame lasted long after his death. His music was performed a lot and copied by other composers in the 1500s. Important figures like Martin Luther praised his work. Even though his fame was later overshadowed by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina in the Baroque era, people still studied his music. In the 1900s, there was a new interest in early music. Josquin's importance was rediscovered, and he is now seen as a central figure in Renaissance music. His music is still recorded and performed by early music groups today. In 2021, the 500th anniversary of his death was celebrated worldwide.

Who Was Josquin des Prez?

Josquin's full name was Josquin Lebloitte dit des Prez. We learned this from old documents found in Condé-sur-l'Escaut. These papers from 1483 show he was the nephew of Gille Lebloitte dit des Prez. His first name, Josquin, is a shorter version of Josse. This was a common name in Flanders and Northern France back then.

His family had used the name "des Prez" for at least two generations. This might have been to tell them apart from other parts of the Lebloitte family. The reason they used "des Prez" as a nickname (or dit name) is still a bit of a mystery.

Josquin's name was spelled in many ways in old records. For example, his first name appeared as Gosse, Jodocus, or Josquinus. His last name was sometimes de Prato, Desprez, or des Prés. In one of his motets, Illibata Dei virgo nutrix, he spelled his name out as an acrostic: IOSQVIN Des PREZ. Today, most scholars just call him Josquin.

Josquin's Life Story

Growing Up and Early Career

Where Was Josquin Born?

We don't know much about Josquin's early life. Historians have debated the details for centuries. It's even a mystery exactly when and where this great composer was born! For a long time, people thought he was born around 1440. But new information suggests he was born later, around 1450, or no later than 1455. This means he was similar in age to other composers like Loyset Compère and Heinrich Isaac.

Josquin's father worked as a policeman. He disappears from records after 1448. We know nothing about Josquin's mother. Around 1466, Josquin was named as the heir by his uncle and aunt, Gille Lebloitte dit des Prez and Jacque Banestonne. This might have happened after his father passed away.

Josquin was born in a French-speaking part of Flanders. This area is now in northeastern France or Belgium. Even though he lived in Condé later, he said he wasn't born there. The only clue about his birthplace is a legal document. In it, Josquin said he was born "beyond Noir Eauwe," which means 'Black Water'. Scholars have many ideas about which river this refers to.

His Youth and Learning Music

There are no official documents about Josquin's education. Some historians think he might have been a choirboy at Saint-Géry in Cambrai. Others suggest he was a choirboy with his friend Jean Mouton at Saint-Quentin. This church was an important place for royal music. Josquin might have made connections there that helped him later with the French royal chapel.

He might have studied with Johannes Ockeghem, a leading composer whom Josquin admired greatly. Josquin even wrote a sad song (a lamentation) when Ockeghem died, called Nymphes des bois. While there's no solid proof of this, Josquin did use Ockeghem's music in some of his own pieces. For example, his motet Alma Redemptoris mater/Ave regina caelorum starts like Ockeghem's motet Alma Redemptoris mater.

Josquin was definitely influenced by Guillaume Du Fay's music. He might have been connected to Cambrai Cathedral too. A motet by Compère, written before 1474, lists a "des Prez" among the musicians there. This could have been Josquin.

Starting His Career

The first clear record of Josquin working is from April 19, 1477. He was a singer in the chapel of René of Anjou in Aix-en-Provence. He stayed there until at least 1478. After that, his name disappears from records for five years. He might have continued working for René, or joined other singers to serve Louis XI of France.

Josquin's early motet Misericordias Domini in aeternum cantabo might be a musical tribute to King Louis XI. Another idea is that Josquin joined Ascanio Sforza's household in 1480. If so, he might have written his Missa Hercules Dux Ferrariae for Ercole d'Este around this time. A collection of chansons (French songs) from this period includes six by Josquin. Adieu mes amours and Que vous ma dame were especially popular.

In February 1483, Josquin returned to Condé to claim his inheritance. His aunt and uncle might have died when Louis XI's army attacked the town in 1478. The church in Condé gave Josquin "wine of honor." This was because he was a distinguished visitor who had already served two kings. Josquin hired many people to handle his inheritance, which suggests he was quite wealthy. This wealth might have allowed him to travel a lot later in life.

Travels and Work in Italy

Milan and Other Places

| Date | Location | What We Know |

|---|---|---|

| March 1483 | Condé | Certain |

| August 1483 | Left Paris | Possible |

| March 1484 | Rome | Possible |

| May 15, 1484 | Milan | Certain |

| June–August 1484 | Milan (with Ascanio) | Certain |

| Up to July 1484 | Rome (with Ascanio) | Certain |

| July 1485 | Planned to leave (with Ascanio) | Certain |

| 1485 – ? | Hungary | Possible |

| January–February 1489 | Milan | Certain |

| Early May 1489 | Milan | Probable |

| June 1489 | Rome (in Sistine Chapel Choir) | Certain |

Records show Josquin was in Milan by May 15, 1484. He might have visited Rome in March 1484. He was hired by the House of Sforza and began working for Cardinal Ascanio Sforza on June 20, 1484. Josquin was already famous as a composer. His wealth or a strong recommendation might have helped him get this important job.

While working for Ascanio, Josquin asked for special permission to be a rector (a church leader) at Saint Aubin. This was granted even though he wasn't a priest yet. The famous motet Ave Maria ... Virgo serena was likely written around 1485.

Josquin went to Rome with Ascanio in July 1484 for a year. He might have also gone to Paris later for a legal matter. Around this time, the poet Serafino dell'Aquila wrote a poem to Josquin. It asked him not to be sad if his "sublime genius" wasn't paid enough. Between 1485 and 1489, Josquin might have worked for Matthias Corvinus in Hungary. Some scholars doubt this, but others believe it's likely. Josquin was back in Milan in January 1489 and met the composer Franchinus Gaffurius there.

Working in Rome

From June 1489 until at least April 1494, Josquin was a member of the papal choir in Rome. He served under Pope Innocent VIII and then Pope Alexander VI. Josquin's arrival brought much-needed prestige to the choir. Two months after he arrived, Josquin started claiming various benefices (church positions that provided income). He was allowed to hold three benefices at once, even without living there or speaking the local language. This was a special privilege.

The Sistine Chapel's payment records give us the best information about Josquin's time there. However, records from April 1494 to November 1500 are missing. So, we don't know exactly when he left Rome.

After some restoration work in the Sistine Chapel in the late 1990s, the name JOSQUINJ was found carved into the choir gallery wall. This is one of almost 400 names carved there by singers. It's very likely this refers to Josquin des Prez. An old book from 1711 also mentions Josquin's name being "sculpted" in the chapel's choir room. While it's not a true signature, it might be the closest we have to Josquin's own mark.

Time in France

New documents found since the late 1900s have given us more clues about Josquin's life between 1494 and 1503. At some point, he became a priest. In August 1494, he visited Cambrai. He might have returned to Rome soon after. There's no clear evidence of his activities from 1494 to 1498. Some suggest he stayed in Cambrai during these years.

Two letters suggest Josquin might have worked for the Sforza family in Milan again around 1498. However, it's unclear if the "Juschino" mentioned was Josquin des Prez. He probably didn't stay in Milan long because his former employers were captured during Louis XII's invasion in 1499. Before he left, he likely wrote two secular pieces: the popular El Grillo ("The Cricket") and In te Domine speravi ("I have placed my hope in you, Lord"). The latter might refer to the religious reformer Girolamo Savonarola, who was executed in 1498.

Josquin was probably in France in the early 1500s. Documents from 2008 show he visited Troyes twice between 1499 and 1501. It was confirmed that he had a benefice (a church position) at Saint-Quentin by May 30, 1503. These positions were usually gifts from the French king to royal household members. This suggests Josquin worked for Louis XII.

A story from 1547 says that Josquin wrote the motet Memor esto verbi tui servo tuo ("Remember thy promise unto thy servant") to gently remind the king to keep his promise of a benefice. When he received it, Josquin supposedly wrote Bonitatem fecisti cum servo tuo, Domine ("Lord, thou hast dealt graciously with thy servant") to show thanks. However, this second motet is now thought to be by another composer, Carpentras. Some of Josquin's other works, like Vive le roy, might also be from his time in France.

Working in Ferrara

Josquin arrived in Ferrara by May 30, 1503. He was there to work for Ercole I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara. The Duke was a big supporter of the arts and had been trying to find a replacement for his choirmaster, who had recently died. Josquin's salary of 200 ducats was the highest ever for a member of the Duke's chapel.

Two letters from the Duke's talent scouts explain how Josquin came to Ferrara. One letter said: "My lord, I believe that there is neither lord nor king who will now have a better chapel than yours if your lordship sends for Josquin." This shows how highly Josquin was regarded. One letter also suggests Josquin might have been a "difficult colleague" and very independent about his music. Some historians see this as proof that people recognized his genius.

While in Ferrara, Josquin wrote some of his most famous pieces. These include the serious motet Miserere mei, Deus, which became very popular. The Missa Hercules Dux Ferrariae is also from this time. Josquin didn't stay in Ferrara long. A terrible outbreak of the plague in 1503 caused many people to leave, including Josquin by April 1504. His replacement, Obrecht, died of the plague the next year.

Later Years in Condé

Josquin probably moved from Ferrara back to his home region of Condé-sur-l'Escaut. He became the provost (a high-ranking church official) of the Notre-Dame church on May 3, 1504. This job gave him political duties and put him in charge of many church workers, including canons, chaplains, and choirboys. This was a good place for him in his old age. It was near where he was born, had a famous choir, and was a leading music center.

Very few records from this time survive. He bought a house in September 1504 and sold one in November 1508. In his later years, Josquin composed many of his most admired works. These include the masses Missa de Beata Virgine and Missa Pange lingua. He also wrote motets like Benedicta es and chansons like Mille regretz. His music became widely known across Europe thanks to the printer Ottaviano Petrucci. Petrucci gave Josquin's compositions a special place and reissued them many times.

On his deathbed, Josquin left money for his work, Pater noster, to be performed during church processions. He died on August 27, 1521. He left his belongings to the church in Condé. He was buried in front of the church's main altar. Sadly, his tomb was destroyed later during wars or the French Revolution.

Josquin's Music Style

After Du Fay died in 1474, music was changing a lot. Josquin and other composers moved between different parts of Europe, bringing new ideas. Josquin is known for three main musical developments:

- He moved away from long, flowing melodies on a single syllable. Instead, he focused on shorter, easily recognizable musical ideas (motifs). These motifs would pass from one voice to another, making the music feel more connected.

- He used a lot of imitation in his music. This means one voice would sing a melody, and then other voices would copy it. This made the music sound unified and rhythmic.

- He paid close attention to the words. The music was designed to highlight the meaning of the text. This was an early form of "word painting," where the music reflects the emotions or actions in the lyrics.

These changes show how music moved from the earlier styles of Du Fay and Ockeghem to the later Renaissance composers. Josquin was a professional singer his whole life, so almost all his music is for voices. He mainly wrote in three types of music: the mass, the motet, and the chanson (French song). He wrote more music than almost any other composer of his time. It's hard to know the exact order in which he wrote his pieces.

Masses by Josquin

The mass is the main church service in the Catholic Church. Composers in the 14th century started writing polyphonic (multi-voiced) music for the main parts of the mass. By Josquin's time, masses were usually long, five-movement pieces. Composers like Du Fay and Ockeghem had already written famous masses.

Josquin helped develop the mass genre a lot. His masses are usually for four voices. They are often less experimental than his motets. This might be because many of his masses were written earlier in his career.

Josquin's masses can be grouped into different styles:

- Canonic masses: These have one or more voices that strictly copy another voice.

- Cantus firmus masses: These use an existing tune (the cantus firmus) in one voice, while the other voices are composed more freely.

- Paraphrase masses: These are based on a popular single-line song. The song's melody is used freely in all voices, with many changes.

- Parody masses: These use parts of a polyphonic song. Material from all voices of the original song is used, not just the melody.

- Solmization masses: These use notes taken from the syllables of a name or phrase.

Josquin was a pioneer in paraphrase and parody masses. Many of his works mix different styles, making them hard to categorize. He tried to get as much variety as possible from his musical material.

Canonic Masses

Josquin's two canonic masses are not based on existing tunes. This makes them different from most other canonic masses of the time. His Missa ad fugam is the earlier one. It has a main musical idea that repeats at the beginning of all five movements. The copying (canon) is mostly in the highest voice.

His Missa sine nomine was written later in his life. In this mass, the way the voices copy each other changes more. The other voices also join in the imitation, making the music more integrated.

Cantus Firmus Masses

The cantus firmus technique was very common before Josquin's mature period. Josquin used this technique early on. His Missa L'ami Baudichon is one of his earliest masses. It's based on a secular tune similar to "Three Blind Mice".

Josquin's most famous cantus firmus masses are based on the popular song "L'homme armé" (meaning "the armed man"). This tune was often used for masses during the Renaissance. His Missa L'homme armé super voces musicales is a very technical piece. It shows off many complex counterpoint techniques. The melody is sung on different notes of the musical scale. The later Missa L'homme armé sexti toni is like a musical fantasy on the "armed man" theme. It also uses the paraphrase technique, where parts of the tune appear in all voices.

Paraphrase Masses

In a paraphrase mass, the original tune (which is usually a single melody) is decorated and used in all voices. Josquin used this technique in several masses. His early Missa Gaudeamus also includes elements of cantus firmus and canon. The Missa Ave maris stella is another early work that paraphrases a Marian hymn. It's one of his shortest masses.

His late Missa de Beata Virgine uses plainchants (simple church melodies) that praise the Virgin Mary. This was a very popular mass in the 1500s.

The most famous of Josquin's paraphrase masses is the Missa Pange lingua. It's based on a hymn by Thomas Aquinas. This mass was probably the last one Josquin composed. It's like a long musical fantasy on the hymn tune. The melody is used in all voices and all parts of the mass, with elaborate and changing polyphony. One special part is in the Credo, where the music becomes simpler and the tune is in the top voice. This section uses words about Jesus becoming human.

Parody Masses

Guillaume Du Fay was one of the first to write masses based on secular (non-religious) songs. By the early 1500s, composers started using ideas from all voices of an existing polyphonic piece, not just a single melody. This was part of a change from the older cantus firmus masses to the new parody masses. In parody masses, all the voices in the music work together. Josquin's works show the many ways composers borrowed from other music during this time.

Six works are usually linked to Josquin that borrow from polyphonic pieces. The Missa Di dadi uses a canon (strict copying) and is based on a song by Robert Morton. The Missa Fortuna desperata is based on a popular Italian song. Josquin used each of the song's voices as a cantus firmus. The Missa Mater Patris is probably the earliest true parody mass by any composer. It's based on a three-voice motet by Antoine Brumel.

Solmization Masses

A solmization mass uses musical notes taken from a word or phrase. The earliest known mass using this style is the Missa Hercules Dux Ferrariae. Josquin wrote this for Ercole I d'Este. It uses the musical syllables from the Duke's Latin name, 'Hercules Dux Ferrariae'. This gives the notes D–C–D–C–D–F–E–D. This mass is the most famous work to use this technique.

Another Josquin mass that uses this technique is the Missa La sol fa re mi. It's based on the French phrase 'laisse faire moy' ("let me take care of it"). The whole mass is built around this musical idea. A story says Josquin wrote this mass as a joke about an aristocrat who used this phrase to dismiss people.

Motets by Josquin

Josquin's motets are his most famous and influential works. Their style varies a lot. Some are simple, with block chords and clear words. Others are complex, with lots of imitation where the music is more important than the words. He also wrote settings of psalms that combined these styles. Most of his motets are for four voices. Josquin was also a leader in writing motets for five and six voices.

Many of his motets use specific compositional rules. Others are freely composed. Some use a cantus firmus to unify the piece. Some are canonic, and others use a repeated musical idea (motto). Josquin often used imitation in his motets. This means that each new line of text would be introduced by one voice, and then copied by the others. This is clear in his motet Ave Maria ... Virgo serena.

Few composers before Josquin wrote polyphonic psalm settings. These make up a large part of his later motets. His famous settings include Miserere (Psalm 51) and two settings of De profundis (Psalm 130). These are considered some of his greatest achievements. Josquin also wrote a new type of piece called a motet-chanson. These had a Latin church melody in the lowest voice, while the other voices sang a secular French text. The French text often related to the Latin text.

Josquin's Secular Music

Josquin wrote many French chansons (songs) for three to six voices. Some were probably meant to be played by instruments. In his chansons, he often used a cantus firmus, sometimes a popular song. In other works, he used a tune from a different text, or he wrote a completely new song. Another technique he used was to take a popular song and write it as a canon (strict imitation) between two inner voices. Then he would add new melodies and a new text around it. He did this in his famous chanson, Faulte d'argent.

Josquin's earliest chansons were probably written in northern Europe. He didn't strictly follow the rules of the formes fixes (fixed patterns of repetition) that were common then. Instead, he often wrote his early chansons with strict imitation, like his sacred works. He was one of the first to write chansons where all voices were equally important. Many of his chansons have a lighter feel and faster tempo than his motets. Some were almost certainly meant for instruments. Josquin's most famous chansons were widely known in Europe. These include his sad song for Ockeghem, Nymphes des bois/Requiem aeternam, and Plus nulz regretz.

Josquin also wrote at least three pieces in the style of the frottola. This was a popular Italian song form he would have heard in Milan. These songs, like Scaramella and El grillo, are simpler than his French chansons. They are almost always clear and homophonic (all voices moving together). They are still among his most performed pieces today.

Portraits of Josquin

(Second) The Portrait of a Musician by Leonardo da Vinci, from the mid-1480s. Some people think the person in this painting is Josquin.

A small woodcut (a print from a carved piece of wood) is the most common image of Josquin. It was printed in a book in 1611 and is the earliest known picture of him. It was probably based on an oil painting that used to be in a church. Church documents found in the 1990s confirm this painting existed. It might have been painted during Josquin's lifetime. Sadly, the painting was destroyed in the late 1500s. We don't know for sure if the woodcut is a very accurate copy of the original painting.

The Portrait of a Musician, often thought to be by Leonardo da Vinci, shows a man holding sheet music. This has led many to believe he is a musician. The painting is from the mid-1480s. Some scholars have suggested the man is Josquin. However, the painting doesn't look like the woodcut, and Josquin was a priest in his mid-thirties, while the person in the painting looks younger. Still, some historians think it's possible it's Josquin.

Another portrait from the early 1500s is often linked to Josquin. It's usually thought to be by Filippo Mazzola and to show the Italian music theorist Nicolò Burzio. The man in the painting is holding a changed version of Josquin's canon Guillaume se va chauffer. Some say the subject looks similar to the woodcut portrait. But there's not enough proof to say for sure that it's Josquin.

Josquin's Legacy

His Influence on Music

Josquin is described as the first composer in Western music history who was not forgotten after he died. He is called the "towering composer of the Renaissance." His influence on music in the 1500s is compared to that of Beethoven in the 1800s.

His popularity meant that other composers copied him. Some publishers even falsely put his name on works after he died to sell more music. This led to a famous saying: "now that Josquin is dead, he is producing more compositions than when he was still alive." The issue was complex, with similar names and works that quoted Josquin causing confusion. Josquin might have had students like Jean Lhéritier and Nicolas Gombert.

Many composers wrote sad songs (laments) after Josquin's death. These included works by Benedictus Appenzeller and Nicolas Gombert. Josquin's music traveled widely after he died, more than that of Du Fay or Ockeghem. Copies of his motets and masses are found in Spanish cathedrals from the mid-1500s. The Sistine Chapel performed his works regularly into the 1600s. Instrumental versions of his music were also published. Josquin is seen as the "master architect" of High Renaissance music. Almost every major composer of the later Renaissance copied or quoted his works.

His Reputation Over Time

We don't know much about Josquin's reputation during his lifetime. But his masses were praised, and music theorists wrote about his works. His popularity is also clear because his music was the first to have entire books of masses dedicated to just one composer.

After Josquin died, important thinkers like Martin Luther praised him. Luther famously said, "he is the master of the notes. They must do as he wills; as for the other composers, they have to do as the notes will."

In the 1600s, with the rise of Baroque music, Josquin's fame lessened. He was overshadowed by Palestrina. But in the late 1700s, people became interested in Netherlandish music again. In the 1860s, historian August Wilhelm Ambros called Josquin "one of the towering figures of Western music history." His research helped create the basis for modern studies of Josquin.

In the early 1900s, Josquin's status began to rise again. A new edition of his complete works started in the 1920s. A major conference in 1971 firmly placed Josquin at the center of Renaissance music. The New Josquin Edition began publishing in 1987.

Recently, some scholars have questioned if Josquin has been praised too much. His list of works has been reduced, with many pieces once thought to be his now considered doubtful. Also, parts of his life story have been rewritten because he was confused with people who had similar names. While there's no doubt about his importance, some argue that other composers of his time were equally important. Despite these debates, Josquin remains one of the most important figures in music history.

Since the 1950s, Josquin's music has become a key part of the repertoire for many early music vocal groups. His music is often recorded. The The Tallis Scholars have recorded all of Josquin's masses. In 2021, the 500th anniversary of Josquin's death was widely celebrated around the world.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Josquin des Prés para niños

In Spanish: Josquin des Prés para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |