Kakapo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kākāpō |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Celebrity kākāpō Sirocco on Maud Island | |

| Conservation status | |

Nationally Critical (NZ TCS) |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Strigops

|

| Species: |

habroptilus

|

| Synonyms | |

|

Strigops habroptila |

|

The kākāpō (kah-KƏ-poh), also called the owl parrot, is a very special type of parrot. Its name comes from the Māori words for "parrot" and "night". This large, green parrot is flightless, meaning it can't fly. It's also nocturnal, so it's active at night. Kākāpō live only in New Zealand.

These unique birds can grow up to 64 cm (25 in) long. They have beautiful yellow-green feathers with dark spots, a face like an owl, and a big grey beak. They have short legs, large blue feet, and small wings and tail. The kākāpō is the only flightless parrot in the world. It's also the heaviest parrot and can live for a very long time, possibly up to 100 years! Males weigh between 1.5–3 kilograms (3.3–6.6 lb) and females between 0.950–1.6 kilograms (2.09–3.53 lb).

Kākāpō are very rare and are critically endangered. There are only 204 known adult kākāpō left. Each one has a name and a tag. They live on four small islands off New Zealand that have been cleared of predators. Long ago, Māori hunted kākāpō. Later, when Europeans arrived, they brought new predators like cats, rats, and stoats. These animals nearly wiped out the kākāpō. People started trying to save them in the 1890s, but the most successful efforts began in 1995 with the Kākāpō Recovery Programme.

Most kākāpō live on two predator-free islands: Codfish / Whenua Hou and Anchor. Here, they are watched very closely. A third island, Little Barrier / Hauturu Island, is also being tested as a home for them.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name kākāpō comes from the Māori words kākā (parrot) and pō (night). This name perfectly describes this night-loving parrot!

The scientific name for the kākāpō is Strigops habroptilus. It was given by an English bird expert, George Robert Gray, in 1845. The name Strigops means "owl face" in Ancient Greek, because of its owl-like features. Habroptilus means "soft feather", which describes its very soft feathers.

The kākāpō is so unique that it's in its own special group of parrots. It's related to the kākā and the kea, which are also from New Zealand. These three birds are part of a very old parrot family, the Strigopoidea, which separated from other parrots millions of years ago when New Zealand broke away from a supercontinent called Gondwana.

Meet the Kākāpō

The kākāpō is a big, round parrot. Adults are about 58 to 64 cm (23 to 25 in) long. Males are usually bigger than females. Males can weigh around 2 kg (4.4 lb), while females are about 1.5 kg (3.3 lb). Kākāpō are the heaviest parrots alive today. They weigh about 400 g (14 oz) more than the largest flying parrot, the hyacinth macaw.

Kākāpō can't fly because their wings are too short for their size. Also, they don't have a strong keel (a bone on the chest where flight muscles attach). They use their wings for balance or to slow down when jumping from trees. Unlike most birds, kākāpō can store a lot of body fat.

Their feathers are yellowish moss-green with black or dark brown spots. This helps them blend in perfectly with the plants around them. Their feathers are very soft because they don't need to be strong for flying. The kākāpō has a clear facial disc of fine feathers, just like an owl. This is why early European settlers called it the "owl parrot." Around its beak, it has delicate feathers that look like whiskers. These might help the kākāpō feel the ground when it walks with its head down.

Female kākāpō look a bit different from males. They have a narrower head, a longer beak, and more slender, pinkish-grey legs and feet. Their tail is also longer. Their feather colors are similar to males but are softer. When nesting, females have a bare patch of skin on their belly called a brood patch.

Baby kākāpō are covered in greyish-white fluff, and you can see their pink skin. They get their full feathers when they are about 70 days old. Young kākāpō are a duller green with more black stripes. They also have shorter tails, wings, and beaks.

Kākāpō make different sounds. Males make loud, low "booming" calls to attract females. They also make a high-pitched, metallic "ching" sound. When they feel threatened, they often make a loud "skraark" noise.

Kākāpō have a great sense of smell, which helps them find food at night. They can tell different smells apart, which is rare for parrots. They also have a unique musty-sweet smell. This smell can sometimes alert predators to their presence.

Because they are nocturnal, kākāpō have adapted their eyes for darkness. Their eyes are very sensitive to light, but they don't see very sharply.

Genetics and Health

Kākāpō have very low genetic diversity because their population became very small (only 49 birds at one point). This means they are very similar to each other genetically. This can lead to problems like lower resistance to diseases and eggs that don't hatch (about 40% of kākāpō eggs are infertile).

Scientists are working to understand kākāpō genetics better. Since 2015, a project called Kākāpō 125 has been sequencing the entire genome (all the genetic information) of every living kākāpō. This is the first time this has been done for an entire species!

Where Kākāpō Live

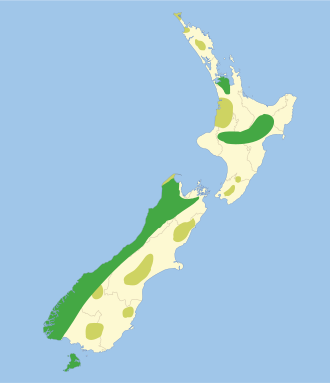

Before humans arrived, kākāpō lived all over New Zealand's main islands. They lived in many different places, like grassy areas, scrublands, and forests. They could survive in hot, dry summers and cold, snowy winters. They seemed to like forests with lots of different trees that produced fruit.

Today, kākāpō only live on special islands where there are no predators.

Life and Habits

The kākāpō is mostly active at night. During the day, it rests hidden in trees or on the ground. At night, it moves around its territory.

Even though they can't fly, kākāpō are excellent climbers. They can climb to the very tops of tall trees. They can also "parachute" down by jumping and spreading their wings, gliding a short distance. Because they don't fly, they don't need much energy. They can live on small amounts of food or food that isn't very nutritious.

Kākāpō are herbivores, meaning they only eat plants. They eat fruits, seeds, leaves, stems, and roots. When they eat, they often leave behind crescent-shaped wads of chewed-up plant fibers. These are called "browse signs" and show that a kākāpō has been there.

They have strong legs and can walk several kilometers. A female might walk 1 km (0.6 mi) each night to find food for her chicks. Males might walk up to 5 km (3 mi) to their mating areas during breeding season.

Young kākāpō like to play fight. Kākāpō are also very curious and sometimes interact with people. Conservation workers who care for them say that each kākāpō has its own unique personality!

In the past, kākāpō were good at avoiding their natural predators, which were birds of prey like the New Zealand falcon and the giant Haast's eagle. Kākāpō evolved to be nocturnal and have camouflage feathers to hide from these daytime hunters. When a kākāpō feels threatened, it freezes, blending in with the plants. However, these defenses didn't work against the new mammal predators that humans brought to New Zealand. Mammals hunt at night and use their strong sense of smell and hearing, which the kākāpō's defenses weren't designed for.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The kākāpō is the only flightless parrot in the world that uses a special mating system called a lek. In a lek, male birds gather in an area and compete to attract females. Females visit the lek to choose a mate.

During mating season, males go to hilltops and ridges to set up their own mating courts. These courts can be up to 5 kilometres (3 mi) from their usual homes. Males stay in their court area throughout the season. At the start, males might fight to get the best spots. They raise their feathers, spread their wings, open their beaks, and make loud screeches and growls. Sometimes, these fights can cause injuries.

Kākāpō don't breed every year. They only breed when certain trees, especially the rimu tree, produce a lot of fruit and seeds. This happens only every three to five years. In these "mast" years, males will make loud "booming" calls for 6–8 hours every night for several months. These booms can be heard over 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) away!

Each male digs one or more saucer-shaped holes in the ground called "bowls." These bowls are about 10 centimetres (4 in) deep and are just big enough for the bird. The kākāpō is one of the few birds that actually builds its mating area. The bowls are often next to rocks or tree trunks to help the sound travel further. The males connect their bowls with a network of trails.

Females are drawn to the booming calls. They might walk several kilometers to reach the lek. Once a female enters a male's court, he performs a special dance. He rocks from side to side, makes clicking noises with his beak, turns his back to her, spreads his wings, and walks backward.

A female kākāpō lays 1–4 eggs per breeding cycle, a few days apart. She nests on the ground, hidden under plants or in hollow tree trunks. The female sits on her eggs, but she has to leave them every night to find food. Predators can eat the eggs, and the embryos can get cold if the mother is away too long. Kākāpō eggs usually hatch in about 30 days. The chicks are fluffy and grey and can't do much on their own. The female feeds the chicks for three months, and they stay with her for a few more months after they learn to move around.

Kākāpō live a long time, usually around 60 years. They don't start breeding until they are older. Males start booming around 5 years old. Females were thought to start breeding at 9 years old, but some 5-year-old females have now had chicks. Because they breed so rarely, kākāpō have one of the slowest reproduction rates among birds.

Interestingly, a female kākāpō can change the number of male or female chicks she has depending on how healthy she is. A very healthy female tends to have more male chicks, which are bigger.

Feeding Habits

The kākāpō's beak is perfect for grinding food into tiny pieces. This is why they have a very small gizzard (a part of the stomach that grinds food) compared to other birds their size. They eat only plants, including native plants, seeds, fruits, pollen, and even the soft wood under tree bark. They especially love the fruit of the rimu tree. When rimu fruit is plentiful, they will eat only that.

When a kākāpō eats, it strips out the good parts of the plant and leaves behind a ball of indigestible fiber. These little clumps are a clear sign that a kākāpō has been feeding nearby. Scientists believe kākāpō use bacteria in their gut to help them digest plant material.

The kākāpō's diet changes with the seasons. They eat different plants throughout the year.

Saving the Kākāpō

Long ago, kākāpō were one of the most common birds in New Zealand. But their numbers have dropped hugely since humans arrived. Today, they are "Nationally Critical," which means they are in extreme danger. People have been trying to save them since the 1890s. The most successful effort is the Kākāpō Recovery Programme, which started in 1995.

Kākāpō are fully protected by New Zealand law. It's also against international rules to trade them or their parts.

Human Impact

The first reason kākāpō numbers dropped was the arrival of humans. Māori stories say that kākāpō were found everywhere when the first Polynesians came to New Zealand 700 years ago. Māori hunted kākāpō for food, and used their skins and feathers to make warm, beautiful cloaks.

Because kākāpō can't fly, have a strong smell, and freeze when scared, they were easy prey for Māori hunters and their dogs. Their eggs and chicks were also eaten by the Polynesian rat (kiore), which Māori brought with them. Māori also cleared forests, which reduced kākāpō habitat. By the time Europeans arrived, kākāpō were already gone from many parts of New Zealand.

However, kākāpō numbers dropped even faster after Europeans settled in New Zealand. Starting in the 1840s, settlers cleared huge areas of land for farms, destroying kākāpō homes. They also brought more dogs and other mammal predators like cats, black rats, and stoats.

In the 1880s, many stoats, ferrets, and weasels were released in New Zealand to control rabbits. But these animals also hunted many native species, including the kākāpō. Other animals like deer, which were also brought by humans, ate the same plants as kākāpō, making it harder for the parrots to find food. By the 1920s, kākāpō were gone from the North Island.

Early Efforts to Save Them

In 1891, the New Zealand government made Resolution Island a nature reserve. A caretaker named Richard Henry started moving kākāpō and kiwi from the mainland to this predator-free island. In six years, he moved over 200 kākāpō. But by 1900, stoats had swum to the island and wiped out the kākāpō there within six years.

More attempts were made to move kākāpō to other islands, but they often failed because of predators like feral cats. By the 1970s, people weren't even sure if kākāpō still existed.

Then, in 1977, kākāpō were found on Stewart Island / Rakiura. This was exciting because it was a larger population. However, feral cats were also on Stewart Island and were killing many kākāpō. So, scientists decided to move these kākāpō to islands that were completely free of predators. This big move happened between 1982 and 1997.

The Kākāpō Recovery Programme

In 1995, the Kākāpō Recovery Programme officially began. The main goal was to move all remaining kākāpō to safe islands where they could breed. Four islands were chosen: Maud, Hauturu/Little Barrier, Codfish, and Mana. Sixty-five kākāpō were moved to these islands. Some islands had to be cleared of predators multiple times. Eventually, Little Barrier Island and Mana Island were found not to be ideal. Two new islands, Chalky Island and Anchor Island, became kākāpō sanctuaries.

Extra Food for Mums

A key part of the Recovery Programme is giving extra food to female kākāpō. Kākāpō only breed when certain trees, like the rimu, produce lots of fruit. This happens only every few years. In these breeding years, extra food is given to kākāpō to help the females be healthy enough to have chicks. This also helps them produce more female chicks, which is important for growing the population.

Today, all kākāpō of breeding age on Whenua Hou and Anchor Island get special parrot food. Their weight and how much they eat are carefully watched to keep them in top condition.

Looking After Nests

Kākāpō nests are closely managed by conservation staff. Even though the islands are now predator-free, cameras watch the nests. This lets rangers see what the mothers and chicks are doing. Data loggers record when mothers leave and return, helping rangers know when to check on the chicks. If a mother has too many chicks, or if a chick is sick, rangers might move chicks to another nest or even hand-raise them. In 2019, eggs were sometimes removed to encourage females to lay more eggs, which led to a record 80 chicks!

Keeping Track

To keep track of every kākāpō, each bird has a radio transmitter. Every known kākāpō has a name, and detailed information is collected about each one. GPS transmitters are also being tested to learn more about where the birds move and how they use their habitat. These signals also help rangers know when birds are mating or nesting.

Bringing Them Back

The Kākāpō Recovery Programme has been very successful. The number of kākāpō is growing steadily. The main goal is to have a healthy, self-sustaining population that doesn't need constant human help. Resolution Island is being prepared for kākāpō to be reintroduced there, with all stoats removed. The long-term goal is to have 150 adult female kākāpō.

Fungal Infection

In 2019, a fungal disease called aspergillosis was found in kākāpō. Almost 20% of the population got sick. Many birds had to be flown by helicopter to special veterinary hospitals for treatment.

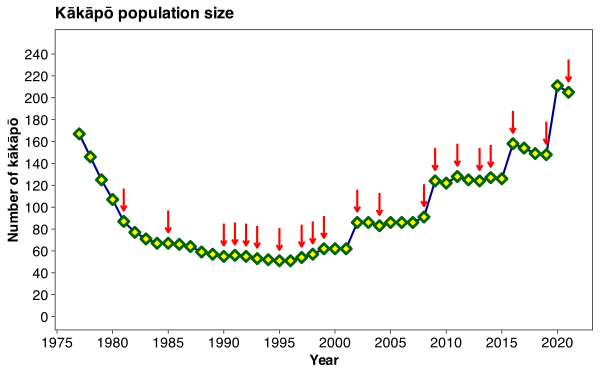

Kākāpō Population Over Time

- 1977: Kākāpō found again on Stewart Island / Rakiura.

- 1989: Most kākāpō moved from Stewart Island to Whenua Hou and Hauturu-O-Toi.

- 1995: Only 51 kākāpō left; the Kākāpō Recovery Programme begins.

- 1999: Kākāpō moved off Hauturu.

- 2002: A good breeding season with 24 chicks.

- 2005: Population reaches 41 females and 45 males. Kākāpō start living on Anchor Island.

- 2009: The total population goes over 100 for the first time since monitoring began.

- December 2010: "Richard Henry," the oldest known kākāpō (possibly 80 years old), dies.

- 2012: Seven kākāpō moved back to Hauturu to try breeding there again.

- March 2014: Population reaches 126.

- 2016: First breeding on Anchor Island; 32 chicks born. Population grows to over 150.

- 2018: Population drops to 149 after 3 birds die.

- 2019: A record-breaking breeding season with 72 chicks. The population reaches 200 birds by August 2019.

- 2022: Population increases to 252 birds after another good breeding season.

Kākāpō in Māori Culture

The kākāpō is important in Māori folklore and beliefs. Māori believed the bird's unusual breeding cycle, linked to trees producing lots of fruit, meant the kākāpō could predict the future. There were stories of kākāpō dropping berries into water to save them for later, which inspired Māori to do the same.

Used for Food and Clothing

Māori considered kākāpō meat a special food. It was hunted when the birds were still common. Some say it tasted like lamb.

During breeding season, the loud booming calls of the males made it easy for Māori hunters to find them. Kākāpō were also caught while feeding or dust-bathing. Hunters used snares, pitfall traps, or dogs. Sometimes they used fire to dazzle the birds at night. The meat was cooked in an earth oven (hāngi) or in boiling oil. The cooked meat could be stored in its own fat for later. Kākāpō tail feathers were used to decorate the storage containers. Māori also ate the bird's eggs, which were whitish and about the size of a kererū egg.

Māori used kākāpō skins with feathers still on, or wove individual kākāpō feathers into flax fiber to make cloaks and capes. These garments were beautiful and very warm. They were highly valued, and the few that still exist today are considered taonga (treasures). There's an old Māori saying: "You have a kākāpō cape and you still complain of the cold," meaning someone is never satisfied. Kākāpō feathers also decorated the heads of taiaha (Māori weapons).

Despite being hunted, kākāpō were also kept as affectionate pets by Māori. European settlers in the 1800s also noted this. George Edward Grey, a governor of New Zealand, once wrote that his pet kākāpō acted "more like that of a dog than a bird."

Kākāpō in the Media

The efforts to save the kākāpō have made the species famous around the world. Many books and documentaries have been made about them.

The BBC's Natural History Unit has featured the kākāpō, including a famous scene with Sir David Attenborough in The Life of Birds. The kākāpō was also part of the book and radio series Last Chance to See by Douglas Adams and Mark Carwardine. Later, Stephen Fry and Mark Carwardine revisited the kākāpō for a TV series. Footage of a kākāpō named Sirocco trying to mate with Carwardine's head became super popular online. Sirocco then became the "spokes-bird" for New Zealand wildlife conservation in 2010. He even inspired the "party parrot" emoji!

The kākāpō has appeared in other TV shows like South Pacific and The Living Planet. In 2019, a New Zealand energy company even ran a "Search for a Saxophonist" to play music for kākāpō to encourage them to mate!

The kākāpō was voted New Zealand's Bird of the Year in both 2008 and 2020.

See also

In Spanish: Kakapo para niños

In Spanish: Kakapo para niños

Images for kids