Karen Uhlenbeck facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Karen Uhlenbeck

|

|

|---|---|

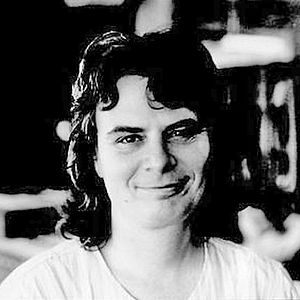

Uhlenbeck in 1982

|

|

| Born |

Karen Keskulla

August 24, 1942 |

| Education | University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (BA) New York University Brandeis University (MA, PhD) |

| Known for | Uhlenbeck's singularity theorem Uhlenbeck's compactness theorem Calculus of variations Geometric analysis Minimal surfaces Yang–Mills theory |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Awards | MacArthur Fellowship Noether Lecturer (1988) National Medal of Science (2000) Leroy P. Steele Prize (2007) Abel Prize (2019) Leroy P. Steele Prize (2020) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions | Institute for Advanced Study University of Texas, Austin University of Chicago University of Illinois, Chicago University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign |

| Thesis | The calculus of variations and global analysis (1968) |

| Doctoral advisor | Richard Palais |

Karen Keskulla Uhlenbeck (born August 24, 1942) is an American mathematician. She is known as one of the people who helped create modern geometric analysis. This is a field of math that uses shapes and measurements to study equations. She used to be a professor at the University of Texas at Austin. Today, she is a visiting professor at the Institute for Advanced Study and Princeton University.

In 2019, Karen Uhlenbeck won the Abel Prize. This award is like the Nobel Prize for mathematics. She won it for her important work on partial differential equations and gauge theory. Her work has had a big impact on analysis, geometry, and mathematical physics. She is the first woman ever to win the Abel Prize since it started in 2003. She gave half of her prize money to groups that help more women get involved in math research.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Karen Uhlenbeck was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on August 24, 1942. Her father, Arnold Keskulla, was an engineer, and her mother, Carolyn Windeler Keskulla, was a teacher and artist. When Karen was a child, her family moved to New Jersey. Her last name, Keskulla, comes from her Estonian grandfather.

She earned her first degree, a B.A., from the University of Michigan in 1964. She then started her advanced studies at New York University. In 1965, she married Olke C. Uhlenbeck, who studied biophysics. When her husband moved to Harvard, she continued her studies at Brandeis University. There, she earned her MA in 1966 and her PhD in 1968. Her PhD advisor was Richard Palais, and her research was about "The Calculus of Variations and Global Analysis."

Career Journey

After finishing her PhD, Karen Uhlenbeck worked at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley. It was hard for her to find a permanent job because of "anti-nepotism" rules. These rules often stopped universities from hiring both a husband and wife, even if they worked in different departments.

In 1971, she became a professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. She didn't like living in Urbana, so she moved to the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1976. In the same year, she and her first husband, Olke Uhlenbeck, separated.

She later moved to the University of Chicago in 1983. By 1988, she had married another mathematician, Robert F. Williams. She then moved to the University of Texas at Austin, where she held an important teaching position. Today, she is a professor emeritus at the University of Texas at Austin. She also works as a visiting scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study and Princeton University.

Important Math Discoveries

Karen Uhlenbeck is a key person in the field of geometric analysis. This area of math uses differential geometry (the study of curved shapes) to understand solutions to differential equations (equations that involve rates of change). She also made contributions to topological quantum field theory and integrable systems.

In the early 1980s, she worked with Jonathan Sacks. They developed ways to understand how smooth or "regular" certain mathematical solutions are. This work helped in studying singularities (points where something becomes undefined or infinite) in harmonic maps. It also helped in understanding the Yang–Mills–Higgs equations in gauge theory.

Her work helped other mathematicians, like Simon Donaldson, who called her 1981 paper "The existence of minimal immersions of 2-spheres" a "landmark paper." This paper showed that by looking deeper into the calculus of variations, mathematicians could find general solutions for harmonic map equations.

She also started a detailed study of minimal surfaces in hyperbolic 3-manifolds. These are like the smallest possible surfaces in certain curved spaces. Her 1983 paper, "Closed minimal surfaces in hyperbolic 3-manifolds," was very important for this.

Simon Donaldson has said that Karen Uhlenbeck's work is fundamental to understanding the math behind the Yang–Mills equations. Her ideas and techniques have had a huge impact on many areas of differential geometry over the past few decades.

Helping Others in Math

Karen Uhlenbeck cares a lot about helping other people in mathematics. In 1991, she helped start the Park City Mathematics Institute (PCMI). Its goal is to offer great learning and career chances for different groups of people in math.

She also helped create the Women and Mathematics Program (WAM) at the Institute for Advanced Study. This program aims to encourage more women to join and stay in the field of mathematics. Jim Al-Khalili, a famous physicist, has called Uhlenbeck a "role model" because she encourages young people, especially women, to pursue careers in math.

Personal Insights

Karen Uhlenbeck describes herself as a "messy reader" and "messy thinker." She has stacks of books on her desk at Princeton's Institute for Advanced Study. After winning the Abel Prize in 2019, she shared a fun story. She said that because there weren't many famous female mathematicians when she was starting out, she looked up to chef Julia Child instead. She admired how Julia Child "knew how to pick the turkey up off the floor and serve it," meaning she was good at solving problems and getting things done.

Awards and Recognitions

In March 2019, Karen Uhlenbeck made history by becoming the first woman to receive the Abel Prize. The award committee praised her for her "pioneering achievements in geometric partial differential equations, gauge theory and integrable systems." They also noted the huge impact of her work on analysis, geometry, and mathematical physics. Hans Munthe-Kaas, who led the award committee, said her theories "revolutionised our understanding of minimal surfaces." She gave half of her prize money to two organizations: the EDGE Foundation and the Institute for Advanced Study's Women and Mathematics (WAM) Program.

She also received the National Medal of Science in 2000. In 2007, she won the Leroy P. Steele Prize for her important work in mathematical gauge theory. She became a MacArthur Fellow in 1983 and a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1986. She was also named an honorary member of the London Mathematical Society in 2008.

The Association for Women in Mathematics honored her in 2020. They recognized her for her amazing contributions to geometric analysis. They also praised her for being a great mathematician despite challenges for women in her time. She used her experiences to create programs that help future generations of women in math.

In 1988, she was the Noether Lecturer for the Association for Women in Mathematics. In 1990, she was a main speaker at the International Congress of Mathematicians. She was only the second woman ever to give such a lecture, after Emmy Noether.

She has also received many other awards, including honorary doctorates from several universities like the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign (2000), Ohio State University (2001), University of Michigan (2004), Harvard University (2007), and Princeton University (2012).

See also

In Spanish: Karen Uhlenbeck para niños

In Spanish: Karen Uhlenbeck para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |