Kituwa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Kituwa

|

|

The Kituwa mound at Ferguson Field

|

|

| Location | U.S. Route 19 east of Bryson City, near Bryson City, North Carolina |

|---|---|

| Area | 20 acres (8.1 ha) |

| NRHP reference No. | 73002239 |

| Added to NRHP | June 4, 2023-11-5 |

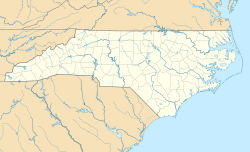

Kituwa (also called Kituwah or Keetoowah) is an ancient Native American settlement. It is near the Tuckasegee River in Swain County, North Carolina. The Cherokee people consider Kituwa their original or "mother" town.

A large earth mound, built around 1000 CE, marks a special ceremonial site here. The Cherokee built a council house on top of this mound. They used it for community meetings and making important decisions. Kituwa is one of the "seven mother towns" in the traditional Cherokee homeland. This area is now part of the Great Smoky Mountains.

The Cherokee lost control of Kituwa in the early 1800s. In the late 1830s, the U.S. government forced most Cherokee people to move. This journey is known as the Trail of Tears. Some Cherokee stayed in North Carolina. Their descendants formed the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI).

Kituwa was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. This was because of its important history and archaeological value. In 1996, the EBCI bought 309 acres of land, including the Kituwa mound. They have studied the site to learn more about its long history. They found ancient burials there. Because of this, they decided to keep this sacred site undeveloped.

Since the mid-1800s, "Keetoowah" has been a special name for some Cherokee. These were often full-blood Cherokee who wanted to keep their traditional ways. Today, the United Keetoowah Band in Oklahoma is a federally recognized tribe. They are descendants of Cherokee who moved west earlier. In the 1800s, some Cherokee groups in Indian Territory formed secret societies. They used the name Keetoowah to keep their rituals and sacred ceremonies alive.

Contents

The Ancient History of Kituwa

Kituwa is home to ancient villages and an earth mound. This mound was built around 1000 CE by people of the South Appalachian Mississippian culture. The Cherokee people believe this site is sacred. It is where their people first came together. Kituwa is located along the Tuckasegee River, near where it meets the Oconaluftee River.

Building large earth mounds was common for many ancient cultures. These mounds were important public structures. They showed the beliefs and political systems of these societies. You can find remains of such mounds across the eastern United States. This includes areas like Tennessee, Georgia, Louisiana, Ohio, and Illinois.

The South Appalachian Mississippian culture began in what is now Western North Carolina around 1000 CE. Sites from this culture, like Kituwa, have been found in river valleys. These ancient peoples were part of large trade networks. These networks connected different groups across the eastern U.S. While some places had many mounds, most towns in North Carolina had one main mound. Smaller villages often grew near these "mother towns."

The Cherokee People and Their Towns

Archaeologists believe that smaller groups eventually joined to form larger tribes. These included the Catawba and Cherokee tribes. The Cherokee built special council houses, also called townhouses. They often built these on top of the earth mounds. If there was no mound, the council house was built in the town's central area. These houses were places for the community to meet and make decisions.

When Europeans first arrived, the Cherokee regularly burned plants on the mound. This helped them farm the land. It may also have been a ritual to keep the mound clear and visible. This burning was a way of sustainable farming.

After the 1830s, European Americans took over Cherokee lands. At Kituwa, they plowed the mound and village area for growing corn. The mound is still there, but it is shorter than it used to be. Eventually, the mound became part of a private farm called Ferguson's Field.

Today, the Kituwa mound is about 170 feet (52 meters) wide. It is five feet (1.5 meters) tall. Archaeologists know it was once taller. Cherokee stories say a council house stood on top of the mound. Inside, a sacred flame was kept burning all the time.

The people of Kituwa were called the Ani-kitu-hwagi. They had a big influence on other Cherokee towns. This included towns along the Tuckasegee and Oconaluftee rivers. These were known as the Out Towns. They also influenced the Middle Towns along the Little Tennessee River. The Valley Towns were further south, along the Hiwassee River, Nantahala River, and Valley River. All these towns were in what is now North Carolina.

The people from this region became known as the Kituwah or Keetoowah. They were seen as protectors of the Cherokee's northern border. They defended against groups like the Iroquois from New York. Because of this, the name Kituwah became a way to refer to all Cherokee people.

During the colonial period, English settlers gave names to different Cherokee towns. Towns along the Savannah River were called the Lower Towns. Towns in eastern Tennessee were called the Overhill Towns. Traders had to cross the Appalachian Mountains to reach them. These were along the lower Little Tennessee River and upper Tennessee River.

The Cherokee language is related to the Iroquoian language family. Most tribes speaking this language lived near the Great Lakes in North America. The Cherokee and other southern Iroquoian-speaking tribes likely moved south long ago. This is supported by Cherokee oral history. They settled in what is now western Virginia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, and Georgia. They consider these areas their homelands.

Today, the ancient Kituwa site is near the Qualla Boundary. The Eastern Band of Cherokee (EBCI) bought Kituwa and 309 acres (1.25 km2) in 1996. This brought the land back under Cherokee control.

Reclaiming the Land in the 20th Century

In 1996, the Eastern Band of Cherokee bought the Kituwa mound and village site. This was a total of 309 acres. In 1997, archaeologists surveyed Kituwa. They found thousands of artifacts. This showed that people had lived there for thousands of years. They found evidence of an early 1700s Cherokee town covering 65 acres (260,000 m2).

The Cherokee people discussed how to use the land. Some EBCI members first wanted to build on the property. But later surveys using special equipment found 15 burials. It is possible there are up to 1000 burials. This is because Cherokee people were often buried in the village where they lived. The surveys also found many hearth sites, including one at the town's center. This was likely linked to the sacred fire in the council house on the mound.

Because of these discoveries, more Cherokee citizens believe the site is very sacred. They feel it should be left undisturbed. They are now planning uses for community wellness and spiritual renewal. The Eastern Cherokee have held youth retreats at the site. These retreats teach traditional ways of spiritual expression.

Cherokee Traditions and Beliefs

Cherokee oral traditions say that all Cherokee settled in Kituwa. This happened after they moved from the Great Lakes region. This migration may have happened as early as 4,000 years ago. Cultural and archaeological evidence supports these stories. However, scholars do not fully agree on when they reached the Southeast.

The ancient Cherokee had a special group of priests called the Ah-ni-ku-ta-ni. This system may have come from another tribe. According to James Mooney, an early researcher, the Cherokee greatly respected and feared these priests. They were not the regular chiefs. There were two types of chiefs: the uguku (owls), or "white" chiefs, who worked for peace. The kolona (ravens), or "red" chiefs, led during times of war.

Some traditional Cherokee call themselves Ah-ni-ki-tu-wa-gi. This means "Kituwa people." The full meaning of the word Kituwa is known to Cherokee speakers. But it is not widely shared because it is sacred. Another meaning for Kituwah is "Ga-Du-Hv." This means "a town" and comes from "Ga-du," meaning "to gather." It refers to Kituwa's role as a mother town.

Honoring the "mother town" was like honoring Selu, the Cherokee Corn Mother. This is part of the ancient Green Corn Ceremony. Honoring mothers is a very important idea in Cherokee culture. Well into the 20th century, the Cherokee had a matrilineal system. This meant that clan membership, inheritance, and status came from the mother's family. A child was considered part of their mother's family and clan.

The Green Corn Ceremony includes an ancient social dance called ye-lu-le. This means "to the center." During the dance, people shout ye-lu-le and move toward the fire. This dance symbolizes the sacred fire given to the people in their legends. In traditional Cherokee society, new fire coals were carried to all Cherokee towns. These coals were used to start ceremonial fires before new corn could be eaten. Home fires were put out before the ceremonies. They were then relit from the coals of the Green Corn Dances.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |