Konstantin Stanislavski facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Konstantin Stanislavski

Константин Станиславский |

|

|---|---|

|

|

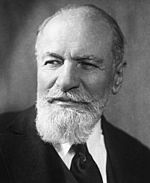

| Born | Konstantin Sergeyevich Alekseyev 17 January [O.S. 5 January] 1863 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | 7 August 1938 (aged 75) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow |

| Occupation | Actor Theatre director Theatre theorist |

| Literary movement | Naturalism Symbolism Psychological realism Socialist realism |

| Notable works | Founder of the MAT Stanislavski's system An Actor's Work An Actor's Work on a Role My Life in Art |

| Spouse | Maria Petrovna Perevostchikova (stage name: Maria Lilina) |

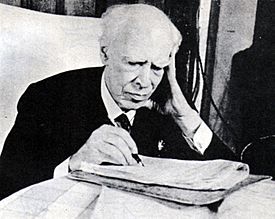

Konstantin Stanislavski (born Konstantin Alekseyev; 1863–1938) was a very important Russian theatre artist. He was known as a great actor and director. But his biggest impact came from his special "system" for training actors. This system helps actors prepare for roles and rehearse.

Stanislavski (which was his stage name) acted and directed as a hobby until he was 33. Then, he helped start the famous Moscow Art Theatre (MAT) with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko. Their meeting lasted an amazing 18 hours! The MAT's tours in Europe (1906) and the US (1923–24) made Stanislavski famous. He helped bring new Russian plays by writers like Anton Chekhov and Maxim Gorky to audiences around the world. He also directed many classic plays.

Stanislavski worked with other famous theatre artists, like Edward Gordon Craig. He also helped train important directors like Vsevolod Meyerhold. In 1928, he had a heart attack on stage, which ended his acting career. But he kept directing, teaching, and writing about acting until he died in 1938. He received high honors, like the title of People's Artist of the USSR.

Stanislavski wrote his autobiography, My Life in Art, which was first published in English in 1924. He didn't really like talking about himself, but a publisher asked him to write it.

Contents

- Understanding Stanislavski's System

- Early Life and Theatre Beginnings

- Amateur Acting and Directing

- Founding the Moscow Art Theatre

- Realistic Plays at the MAT

- Studios and Developing the System

- World War I and Revolution

- Life During the Revolutions

- MAT Tours in Europe and the US

- Soviet Productions and Later Work

- Writing a Manual for Actors

- Developing the Method of Physical Action

- Life Under Stalin

- Final Work and Legacy

- See also

Understanding Stanislavski's System

Stanislavski deeply studied acting and directing. His "system" of acting grew from his efforts to fix problems he saw in performances. He started by planning every detail of a play, from how actors moved to the overall look. He also made sure the cast discussed and analyzed the play together. Even though this worked well, especially for his realistic plays by Anton Chekhov and Maxim Gorky, Stanislavski still wasn't satisfied.

He wanted actors to focus more on their "inner action" and feelings. He started developing techniques for "psychological realism". This meant focusing on the actor's process and teaching. He used theatre studios like labs to try out new ways of training actors. Stanislavski put his techniques into a clear system. It combined ideas from different theatre groups:

- The Meiningen Ensemble's disciplined, unified approach.

- The Maly Theatre's focus on realistic acting.

- André Antoine's realistic staging from the independent theatre movement.

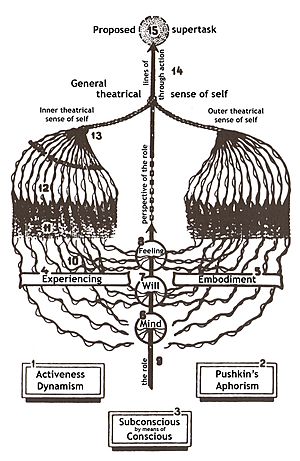

The system helps actors "experience" their roles, rather than just pretending. It uses an actor's conscious thoughts and will to bring out deeper feelings and subconscious behaviors. In rehearsals, actors look for inner reasons for their actions. They also figure out what their character wants to achieve in each moment, which Stanislavski called a "task." He first mentioned his system in 1909, and the MAT officially adopted it in 1911.

Later, Stanislavski added more physical exercises to his system. This became known as the "Method of Physical Action." Instead of long discussions, he encouraged "active analysis." Actors would improvise scenes to understand them. He believed that "the best analysis of a play is to take action in the given circumstances."

Stanislavski opened another studio in 1935 to teach this "Method of Physical Action." His earlier work, taught by his students, greatly changed acting in the West. In the Soviet Union, Stanislavski's system became a leading example for theatre.

Early Life and Theatre Beginnings

Konstantin Stanislavski grew up in one of Russia's richest families, the Alekseyevs. He was born Konstantin Sergeyevich Alekseyev. He chose the stage name "Stanislavski" in 1884 to keep his acting a secret from his parents. Before the 1917 October Revolution, he often used his family's money to fund his theatre experiments. Because his family didn't approve, he only acted as a hobby until he was 33.

As a child, Stanislavski loved the circus, ballet, and puppetry. His family had two private theatres where he could practice. After his first performance in 1877, he started keeping notebooks. These were filled with notes on his acting, ideas, and problems. This habit of self-analysis later led to his famous Stanislavski's system. Instead of going to university, Stanislavski chose to work in his family's business.

He became very interested in "experiencing the role" and even tried to stay in character in real life. In 1884, he started voice training and learned to coordinate his body and voice. He briefly studied at the Moscow Theatre School but left because he didn't like their methods. Instead, he closely watched performances at the Maly Theatre, which was known for its realistic acting.

The Maly Theatre taught him about disciplined acting, long rehearsals, and using observation, imagination, and emotion. Stanislavski called the Maly his "university." One of its students, Glikeriya Fedotova, taught him to reject simply waiting for "inspiration." She stressed the importance of training and interacting with other actors. Stanislavski also admired foreign actors like Ernesto Rossi and Tommaso Salvini, who performed major Shakespearean roles with great emotion.

Amateur Acting and Directing

By age 25, Stanislavski was a well-known amateur actor. He helped create the Society of Art and Literature. Through this group, he acted in plays by famous writers like Molière and Leo Tolstoy. He also started directing plays for the first time. He became interested in the ideas of Vissarion Belinsky, who influenced his view of art.

In 1889, Stanislavski married Maria Lilina. In 1891, he directed Leo Tolstoy's The Fruits of Enlightenment. He called this his first truly independent directing work. Five years later, the Moscow Art Theatre would be his answer to Tolstoy's call for art that was simple and easy to understand.

At this time, Stanislavski directed plays much like Ludwig Chronegk of the Meiningen Ensemble. This meant the director controlled everything, without much input from the actors. From 1894, Stanislavski made detailed prompt-books for plays. Not even the smallest detail could be changed.

While the Meiningen group focused on grand effects, Stanislavski added poetic touches to show everyday life. By carefully controlling every part of the play, including the actors' movements, he felt the "inner meaning of the play was revealed." He wanted to combine the realistic acting of Mikhail Shchepkin with the unified, naturalistic style of the Meiningen group. Stanislavski believed his generation's task was "to free art from old traditions, from tired clichés and to give greater freedom to imagination and creative ability."

Founding the Moscow Art Theatre

Stanislavski's famous meeting with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko in 1897 led to the creation of the Moscow Art Theatre (MAT). Their 18-hour talk is legendary in theatre history.

Nemirovich was a successful playwright, critic, and teacher. Like Stanislavski, he wanted to create theatre for everyone. They had different strengths that worked well together. Stanislavski was great at creating vivid stage pictures. Nemirovich was good at analyzing plays and managing a theatre. They agreed on what old theatre practices to get rid of and set the rules for their new theatre.

They planned a professional theatre company where everyone worked together, not just for individual fame. They wanted to create realistic theatre that would be known worldwide. It would have affordable tickets and combine the techniques of the Meiningen Ensemble and André Antoine's Théâtre Libre. Stanislavski insisted it be a company owned by many people, not just him. Viktor Simov became their main designer.

On the first day of rehearsals in 1898, Stanislavski emphasized that their work was for the community. He described the atmosphere as being more like a university than a theatre. The company learned his method of extensive reading, research, and detailed rehearsals. The actors would discuss the play at a table before physically exploring the actions. This is how Stanislavski's long relationship with Vsevolod Meyerhold began. Meyerhold was so impressed that he called Stanislavski a genius.

Realistic Plays at the MAT

The early work of Stanislavski at the MAT was important for developing a realistic style of performance. In 1898, Stanislavski co-directed the first of his plays by Anton Chekhov. The MAT's production of The Seagull was a huge moment for the new company. It's called "one of the greatest events in the history of Russian theatre." Even with 80 hours of rehearsal (a lot for that time), Stanislavski felt it wasn't enough. The play succeeded because it showed everyday life truthfully, with close-knit acting and a mood that matched the feelings of Russian intellectuals.

Stanislavski then directed other successful Chekhov plays: Uncle Vanya (1899), Three Sisters (1901), and The Cherry Orchard (1904). Working with Chekhov's plays was key for both men. Stanislavski's focus on teamwork and the characters' inner lives made Chekhov want to write for the stage again. Chekhov's plays, which didn't explain everything, forced Stanislavski to look deeper for hidden meanings, which was new in theatre.

Maxim Gorky promised to write plays for the MAT after Stanislavski encouraged him. In 1902, Stanislavski directed Gorky's first two plays, The Philistines and The Lower Depths. For The Lower Depths, the company visited a market where poor people lived. They talked to them to understand their lives. Stanislavski based a character on a former officer he met there. The Lower Depths was a huge success, like The Seagull.

The Cherry Orchard and The Lower Depths stayed in the MAT's repertoire for many years. Besides Chekhov and Gorky, plays by Henrik Ibsen were also important to Stanislavski's work. The MAT staged more Ibsen plays than any other writer in its first 20 years. Stanislavski also directed other important realistic plays.

Studios and Developing the System

After the success of A Month in the Country, Stanislavski asked the MAT board for better facilities to teach young actors. Maxim Gorky advised him to create a studio for research and experiments, not just a school for beginners.

Stanislavski created the First Studio in 1912. Its first members included Yevgeny Vakhtangov and Michael Chekhov, who would become very influential in theatre. Stanislavski chose Leopold Sulerzhitsky to lead the studio. In this focused environment, they experimented with improvisation and self-discovery. They looked for "the creative process common to authors, actors and directors."

Stanislavski created the Second Studio of the MAT in 1916. This studio focused more on teaching. It was where Stanislavski developed the training techniques for his book An Actor's Work (1938).

His experience teaching and directing at his Opera Studio, founded in 1918, also greatly influenced his system. He hoped that applying his system to opera, which is very traditional, would show that his approach worked for all kinds of performances. From this, his idea of "tempo-rhythm" emerged.

World War I and Revolution

Stanislavski was in Germany when World War I started in 1914. He wrote that "death was hovering everywhere." German soldiers stopped his train and accused him of being a spy. He thought he would be executed. But he had an official document mentioning that he had performed for Kaiser Wilhelm during a 1906 tour. When he showed it, the soldiers' attitude changed, and he was eventually sent back to Russia.

The MAT then focused on Russian classics. Stanislavski kept developing his system. He explained his idea of "I am being," which is when the actor and character become one, and subconscious actions take over. He stressed focusing on actions ("What would I do if...") instead of emotions ("How would I feel if..."). He believed actors should notice what's happening, connect with other actors, and understand the fictional world through their senses.

When he prepared for his role in Pushkin's Mozart and Salieri, Stanislavski created a detailed background for his character. But when he tried to show all this detail, the hidden meaning became too much, and the play's words were hard to understand. This made him pay more attention to how language works in plays.

In 1916, Stanislavski's assistant and close friend, Leopold Sulerzhitsky, died. Stanislavski said that Suler had understood him completely and no one had replaced him since.

Life During the Revolutions

Stanislavski welcomed the February Revolution of 1917, which ended the monarchy. He saw it as a "miraculous liberation of Russia." After the October Revolution later that year, the MAT closed for a few weeks. Stanislavski believed these changes offered a chance to create a Russian theatre for everyone.

Vladimir Lenin, who often visited the MAT, praised Stanislavski as "a real artist." He felt Stanislavski's approach was the right direction for theatre. The revolutions changed Stanislavski's finances when his factories were taken over by the state. His MAT salary became his only income. In 1918, Stanislavski was briefly arrested but released the next day.

During the Russian Civil War, Stanislavski focused on teaching his system, directing, and bringing classic plays to new audiences like factory workers and soldiers. In 1921, he was moved from his large house, but Lenin intervened, and Stanislavski was given a new home near the MAT. In 1922, his favorite student, the director Yevgeny Vakhtangov, died.

MAT Tours in Europe and the US

After the state temporarily stopped funding the MAT in 1921, Stanislavski and Nemirovich planned a tour to Europe and the US to earn money for the company. The tour started in Berlin in 1922, then went to Prague, Zagreb, and Paris. In Paris, he met other famous theatre people. He also saw performances by Ermete Zacconi, who impressed him with his control and ability to both "experience" and "represent" a role.

The company arrived in New York City in 1923. Stanislavski said that "America wants to see what Europe already knows." The tour received great reviews and helped American acting develop. Many actors, including the young Lee Strasberg, came to watch and learn. Richard Boleslavsky gave lectures on Stanislavski's system. After New York, they toured other US cities.

A US publisher asked Stanislavski to write his autobiography, My Life in Art. He agreed, even though he preferred to write about his system or the MAT's history. He returned to Europe to work on the book and then started rehearsals for a second US tour. The company toured many more US cities. In 1924, Stanislavski even met President Calvin Coolidge at the White House. The company left the US in May 1924.

Soviet Productions and Later Work

When he returned to Moscow in 1924, Stanislavski revised his autobiography for a Russian edition. He continued to act, playing Astrov in a new production of Uncle Vanya. While Nemirovich was away, Stanislavski led the MAT for two successful years.

With his company now fully trained in his system, Stanislavski focused on the rhythm of plays and the main goals of characters. He told them, "See everything in terms of action." He even threatened to close the theatre if a play by Mikhail Bulgakov was banned. Despite bad press, the play was a hit.

Stanislavski also directed Pierre Beaumarchais' 18th-century comedy The Marriage of Figaro. He moved the story to pre-Revolutionary France and highlighted the democratic views of the characters Figaro and Susanna. His methods for this play added new ideas to his system: analyzing scenes by physical tasks and using the "line of the day" for each character.

Instead of tightly planning every movement, he now worked with broad physical tasks. Actors would respond truthfully to scenes with improvised actions to solve problems. For the "line of the day," an actor would imagine what their character did off-stage to create a continuous experience. This helped justify their actions on stage. The production was a huge success.

In 1928, the MAT celebrated its 30th anniversary. While performing, Stanislavski suffered a massive heart attack. He finished his performance, but then collapsed. This ended his acting career.

Writing a Manual for Actors

In 1926, Stanislavski started writing An Actor's Work, a manual for actors written as a student's diary. He wanted it to be two volumes: one for inner experience and physical acting, and another for rehearsal processes. But because of publishing rules, it became three volumes, published separately.

This arrangement risked making people misunderstand his system, which was meant to be seen as a whole. Many English readers thought the first volume, An Actor Prepares (1936), was the entire system.

Stanislavski worked on the second half of An Actor's Work in 1933. A version of the first volume was published in America in 1935. A more complete Russian edition, An Actor's Work on Himself, Part I, was published in 1938, just after he died. The other parts were published later. In 2008, a complete English translation of An Actor's Work was finally published.

Developing the Method of Physical Action

While recovering in 1929, Stanislavski began planning a production of Shakespeare's Othello. This plan was the first time he explained his "Method of Physical Action" rehearsal process. He first tried this approach in plays like Three Sisters and Carmen in 1934.

Unlike his earlier method of long discussions before physical rehearsals, Stanislavski now encouraged actors to explore actions through "active analysis." He felt too much talk early on confused actors. Instead, they would improvise scenes based on simple physical actions. He believed that if actors truly committed to the truth of their actions, it would bring out real thoughts and feelings.

Stanislavski's view on using "emotion memory" in rehearsals changed over time. He felt that directly trying to force emotions often blocked actors. Instead, he believed focusing on actions (supported by the play's circumstances and "Magic Ifs") was a better way to bring out the right emotional response.

This change also meant more attention to the play's overall structure. In performance, an actor focuses on one step at a time. But to plan the role, the actor needs to see the whole picture. Stanislavski called this the "perspective of the role."

In 1934, Stanislavski worked with American actress Stella Adler in Paris. She was surprised that he didn't emphasize emotion memory, except as a last resort. This news had a big impact in the US, where Lee Strasberg disagreed and refused to change his version of the system.

Life Under Stalin

After his heart attack in 1928, Stanislavski spent his last ten years working from his home in Moscow. He was protected by Joseph Stalin's policy of "isolation and preservation" for famous cultural figures. This helped shield him from the worst parts of Stalin's "Great Terror."

Some articles criticized Stanislavski's system in the early 1930s, calling it too focused on individual feelings. However, after a major writers' congress in 1934, "Socialist realism" became the official art style. While this was bad for other artists, the MAT and Stanislavski's system were seen as perfect examples.

Final Work and Legacy

Because he had trouble finishing his acting manual, Stanislavski decided to open a new studio to ensure his ideas lived on. He wrote, "Our school will produce not just individuals, but a whole company." In 1935, he began teaching teachers the techniques of his system and the Method of Physical Action. The Opera-Dramatic Studio opened in November, with 20 students. Stanislavski planned a four-year program focused on technique.

He worked with students on plays like Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet, focusing on physical actions and the characters' main goals. By June 1938, the students were ready to perform scenes for a small audience. This studio was the most complete example of the training exercises Stanislavski described in his books.

From 1936, Stanislavski regularly met with Vsevolod Meyerhold. They talked about creating a common theatre language. In 1938, they planned to work together on a production and combine Stanislavski's Method of Physical Action with Meyerhold's biomechanical training. On his deathbed, Stanislavski said Meyerhold was "my sole heir in the theatre."

Stanislavski died at his home on August 7, 1938, likely from another heart attack. Thousands of people attended his funeral. Three weeks later, his widow received a copy of the first volume of An Actor's Work, which she called "the labour of his life." Stanislavski was buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, near Anton Chekhov's grave.

See also

In Spanish: Konstantín Stanislavski para niños

In Spanish: Konstantín Stanislavski para niños

- Ion Cojar

- Ivana Chubbuck

- Sanford Meisner

- Lee Strasberg

- Psycho-physical Awareness

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |