Pierre Beaumarchais facts for kids

Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (born January 24, 1732, died May 18, 1799) was a very talented French person. During his life, he was many things: a watchmaker, an inventor, a writer of plays, a musician, a diplomat, and even a spy. He also played a part in both the American and French Revolutions.

Born in Paris as the son of a watchmaker, Beaumarchais became important in French society. He gained influence in the court of King Louis XV as an inventor and music teacher. He made many important friends and business connections. He worked as a diplomat and spy, and he earned a lot of money. However, some expensive legal battles later put his good name at risk.

Beaumarchais was an early French supporter of American independence. He worked to convince the French government to help the American rebels during the American War of Independence. He secretly helped the French and Spanish governments send weapons and money to the rebels. This happened in the years before France officially joined the war in 1778. Later, he tried hard to get back the money he had personally spent on this effort. Beaumarchais was also involved in the early parts of the 1789 French Revolution.

Beaumarchais is probably best known for his plays. His most famous works are the three Figaro plays.

Contents

Early Life and Inventions

Beaumarchais was born Pierre-Augustin Caron in Paris on January 24, 1732. He was the only boy among six children. His father, André-Charles Caron, was a watchmaker. The family was comfortable and Beaumarchais had a happy childhood. He enjoyed music and played several instruments.

From age ten, Beaumarchais went to a "country school" where he learned some Latin. At twelve, he left school to work as an apprentice for his father. He learned the art of watchmaking. He often neglected his work. At one point, his father sent him away, but later allowed him back after he apologized.

At that time, pocket watches were not very accurate. People wore them more as fashion items. Beaumarchais spent almost a year trying to make them better. In July 1753, at age twenty-one, he invented a new part for watches called an escapement. This made watches much more accurate and smaller.

The royal clockmaker, Jean-André Lepaute, was interested in this invention. Lepaute had been a mentor to Beaumarchais. He encouraged the young inventor. However, Lepaute then tried to steal the idea for himself. He wrote a letter to the French Academy of Sciences describing it as his own "Lepaute system." Beaumarchais was very angry. He wrote a strong letter to the same newspaper, saying the invention was his. He asked the French Academy of Sciences to see the proof.

The Academy decided in February that the invention was Beaumarchais's. This made Beaumarchais famous. Soon after, King Louis XV asked him to create a watch for his mistress, Madame de Pompadour. Louis was so impressed that he named Beaumarchais "Purveyor to the King." The Caron family business became very successful.

Rise to Influence

Marriage and New Name

In 1755, Beaumarchais met Madeleine-Catherine Aubertin, a widow. He married her the next year. She helped him get a royal job, and he stopped being a watchmaker. After his marriage, he took the name "Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais." This name came from "le Bois Marchais," a piece of land his new wife owned. He thought the name sounded grander and more noble. His wife died less than a year later, which caused him financial problems.

Royal Connections

Beaumarchais's problems got easier when he was chosen to teach King Louis XV's four daughters to play the harp. His role grew, and he became a music advisor for the royal family. In 1759, Beaumarchais met Joseph Paris Duverney, a rich and older businessman. Beaumarchais helped Duverney get the King's approval for a new military school he was building, the École Royale Militaire. In return, Duverney promised to help Beaumarchais become rich. They became close friends and worked together on many business projects.

With Duverney's help, Beaumarchais gained the title of Secretary-Councillor to the King in 1760–61. This allowed him to join the French nobility. In 1763, he bought another title, Lieutenant General of Hunting, which oversaw royal parks.

Trip to Madrid

In April 1764, Beaumarchais traveled to Madrid, Spain, for ten months. He said he was going to help his sister, Lisette. Her fiancé, José Clavijo y Fajardo, an official, had left her. While in Spain, Beaumarchais was mostly focused on making business deals for Duverney. They wanted special contracts for the new Spanish colony of Louisiana. They also tried to get the right to bring enslaved people to the Spanish colonies in the Americas.

Beaumarchais went to Madrid with a letter of introduction from the Duc de Choiseul, who was now his political supporter. Beaumarchais tried to get Clavijo's support for his business deals by getting him to marry Lisette. He first shamed Clavijo into agreeing to marry her. But when more details about Clavijo's actions came out, the marriage was called off.

Beaumarchais's business deals took a long time. He spent much of his time enjoying the Spanish culture. This experience later influenced his writing. Even though he became friends with important people like the foreign minister Grimaldi, his attempts to get contracts for Duverney failed. He returned home in March 1765. Beaumarchais did not make much money from the trip. However, he gained new experiences, musical ideas, and ideas for characters in his plays.

Playwright

Beaumarchais wanted to become a consul (a government official) in Spain, but his request was denied. Instead, he focused on his business and started to write plays. He had already written short comedies for private shows. Now, he wanted to write for the public theater.

He became known as a writer with his first serious play, Eugénie. It was first performed at the Comédie-Française in 1767. In 1770, he followed this with another play, Les Deux amis.

Figaro Plays

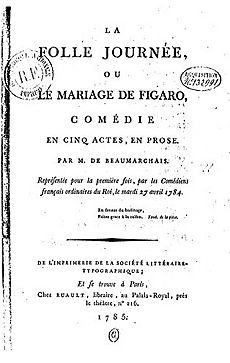

Beaumarchais's famous Figaro plays are Le Barbier de Séville (The Barber of Seville), Le Mariage de Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro), and La Mère coupable (The Guilty Mother). The characters Figaro and Count Almaviva are in all three plays. They show how social attitudes changed before, during, and after the French Revolution.

The first ideas for Almaviva and Rosine appeared in a short, unfinished play called Le Sacristain. Beaumarchais wrote it around 1765. In this play, a character named Lindor pretends to be a monk and music teacher to meet Pauline. This happens while her elderly husband watches closely.

King Louis XVI read an early version of Beaumarchais's play. He said, "this man mocks everything that must be respected in a government." He refused to let it be performed.

The Figaro plays also have some parts of Beaumarchais's own life. Characters like Don Guzman Brid'oison and Bégearss were based on two of Beaumarchais's real-life opponents. The young page Chérubin in The Marriage of Figaro was like Beaumarchais when he was young. Suzanne, the main female character, was based on Beaumarchais's third wife.

Le Barbier de Séville first opened in Paris in 1775. An English version was performed in London a year later. Then, it was shown in other European countries.

The next play, Le Mariage de Figaro, was first approved by the censor in 1781. But King Louis XVI soon banned it after a private reading. Queen Marie-Antoinette and her friends were sad about the ban. However, the King did not like how the play made fun of the nobility. He refused to let it be performed. For the next three years, Beaumarchais gave many private readings. He also made changes to try and get it approved. The King finally allowed it in 1784. The play opened that year and was very popular, even with noble audiences. Mozart's opera based on the play, Le Nozze di Figaro, opened just two years later in Vienna.

Beaumarchais's last play, La Mère coupable, opened in Paris in 1792. All three Figaro plays were very successful. They are still performed often today in theaters and opera houses.

Court Battles

The death of Duverney on July 17, 1770, caused many problems for Beaumarchais. A few months before, they had signed a paper saying Beaumarchais owed Duverney no more money. Duverney's only heir, Count de la Blache, took Beaumarchais to court. He claimed the signed paper was fake. In 1772, the court sided with Beaumarchais. But a judge named Goezman overturned this decision the next year. Beaumarchais tried to bribe Goezman, but failed.

At the same time, Beaumarchais was also in a fight with the Duke de Chaulnes. This led to Beaumarchais being put in jail from February to May 1773. La Blache used Beaumarchais's absence from court. He convinced Goezman to order Beaumarchais to pay back all his debts to Duverney, plus interest and legal costs.

To get public support, Beaumarchais wrote a four-part pamphlet called Mémoires contre Goezman. This made Beaumarchais instantly famous. People saw him as a hero fighting for fairness and freedom. Goezman then sued Beaumarchais. The final decision was unclear. On February 26, 1774, both Beaumarchais and Mme. Goezman (who had taken the bribe) were punished. They lost some of their civil rights. Beaumarchais did not follow many of these rules. Judge Goezman was removed from his job. Also, Goezman's decision in the La Blache case was overturned. The Goezman case was so big that the judges left the courtroom through a back door to avoid the large, angry crowd outside.

American Revolution Support

Before France officially joined the war in 1778, Beaumarchais played a big part. He helped deliver French weapons, money, and supplies to the American army. To secretly send aid to the rebels, he helped create a fake business called Roderigue Hortalez and Company.

To get his civil rights back, Beaumarchais offered his help to King Louis XV. He traveled to London, Amsterdam, and Vienna on secret missions. His first mission was to go to London to destroy a pamphlet. King Louis XV thought it was a lie about one of his mistresses. Beaumarchais was sent to London to convince the French spy Chevalier d'Éon to return home. While there, he started gathering information about British politics. Britain's colonies were having problems. In 1775, fighting broke out between British troops and American rebels. Beaumarchais became a main source of information about the rebellion for the French government. He sent many reports, sometimes with exaggerated rumors about the success of the rebel forces.

Back in France, Beaumarchais started a new plan. King Louis XVI did not want to openly fight with Britain. So, he allowed Beaumarchais to start a business called Roderigue Hortalez and Company. This company was supported by the French and Spanish kings. It supplied the American rebels with weapons, ammunition, clothes, and food. The rebels never paid for these supplies. This plan worked well in 1777. John Burgoyne's army surrendered at Saratoga to a rebel force. This force was largely clothed and armed by the supplies Beaumarchais had sent. It was a big success for him. Beaumarchais was hurt in a carriage accident while rushing to Paris with news of Saratoga. In April 1777, Beaumarchais bought an old 50-gun ship called Hippopotame. He renamed it Fier Rodrigue and used it to carry weapons to the American rebels.

Beaumarchais worked with Silas Deane, a member of the American Committee of Secret Correspondence. For these services, the French Parliament gave Beaumarchais his civil rights back in 1776. In 1778, Beaumarchais's hopes came true. The French government agreed to the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and the Treaty of Alliance. France officially joined the American War of Independence soon after. Spain followed in 1779, and the Dutch Republic in 1780.

The Voltaire Project

After Voltaire died in 1778, Beaumarchais decided to publish all of Voltaire's works. Many of these works were banned in France. He bought the rights to most of Voltaire's writings from a publisher in February 1779. To avoid French censorship, he set up printing presses in Kehl, Germany. He bought all the printing equipment from the famous English type designer John Baskerville. He also bought three paper mills. Seventy volumes were published between 1783 and 1790. This project did not make money. However, Beaumarchais was very important in saving many of Voltaire's later works. These works might have been lost otherwise.

The French Revolution

When the French Revolution began, Beaumarchais was not as popular as before. He felt that the extreme actions of the revolution were putting freedom in danger. He was financially successful, mostly from supplying drinking water to Paris. He had also gained titles in the French nobility. In 1791, he moved into a fancy home across from where the Bastille prison used to be. He spent less than a week in prison in August 1792 for criticizing the government. He was released just three days before a terrible massacre happened in the prison where he had been held.

Even so, he offered his help to the new republic. He tried to buy 60,000 rifles for the French Revolutionary army from Holland. However, he was not able to complete the deal.

Exile and Death

While he was out of the country, Beaumarchais's enemies falsely said he was an émigré. This meant they claimed he was loyal to the old government. He spent two and a half years in exile, mostly in Germany. Later, his name was removed from the list of banned émigrés. He returned to Paris in 1796. He lived the rest of his life there in relative peace. He is buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Boulevard Beaumarchais in Paris is named after him.

Operas Based on His Works

In 1786, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed an opera, Le nozze di Figaro. It was based on Beaumarchais's play The Marriage of Figaro. The words for the opera were written by Lorenzo Da Ponte.

Several composers wrote operas based on The Barber of Seville. Paisiello wrote one in 1782. Although not popular at first, Rossini's 1816 version of Barber is his most successful work. It is still performed often today. In 1966, Darius Milhaud composed an opera, La mère coupable, based on The Guilty Mother.

Beaumarchais also wrote the words for Antonio Salieri's opera Tarare. It first opened in Paris in 1787.

Private Life

Beaumarchais married three times. His first wife was Madeleine-Catherine Franquet, whom he married in 1756. She died about 10 months later. He married Geneviève-Madeleine Lévêque in 1768. She died two years later, likely from tuberculosis. Before her death in 1770, she had a son, Augustin, but he died in 1772. Beaumarchais lived with Marie-Thérèse de Willer-Mawlaz for 12 years before she became his third wife in 1786. They had a daughter named Eugénie.

Beaumarchais was known to care deeply for his family and close friends.

List of Works

- 1760s – Various short comedies for private shows.

- Les Député de la Halle et du Gros-Caillou

- Colin et Colette

- Les Bottes de sept lieues

- Jean Bête à la foire

- Œil pour œil

- Laurette

- 1765(?) – Le Sacristain, a short play (an early version of Le Barbier de Séville)

- 1767 – Eugénie, a drama, first performed at the Comédie-Française.

- 1767 – L'Essai sur le genre dramatique sérieux.

- 1770 – Les Deux amis ou le Négociant de Lyon, a drama, first performed at the Comédie-Française

- 1773 – Le Barbier de Séville ou la Précaution inutile, a comedy, first performed on January 3, 1775, at the Comédie-Française

- 1774 – Mémoires contre Goezman

- 1775 – La Lettre modérée sur la chute et la critique du "Barbier de Sérville"

- 1778 – La Folle journée ou Le Mariage de Figaro, a comedy, first performed on April 27, 1784, at the Comédie-Française

- 1784 – Préface du mariage de Figaro

- 1787 – Tarare, an opera with music by Antonio Salieri, first performed at the Opéra de Paris (full-text)

- 1792 – La Mère coupable ou L'Autre Tartuffe, a drama, first performed on June 26 at the Théâtre du Marais

- 1799 – Voltaire et Jésus-Christ, in two articles.

Related Works

- Clavigo (1774), a play by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe based on Beaumarchais's experiences in Spain.

- Il barbiere di Siviglia, ovvero La precauzione inutile (1782), an opera based on The Barber of Seville, with music by Giovanni Paisiello.

- Le nozze di Figaro (1786), an opera based on The Marriage of Figaro, with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

- Ta veseli dan ali Matiček se ženi (1790) by Anton Tomaž Linhart, a play based on Le Mariage de Figaro.

- Il barbiere di Siviglia (1796), an opera based on the play, music by Nicolas Isouard.

- La pazza giornata, ovvero Il matrimonio di Figaro (1799), an opera based on The Marriage of Figaro, with music by Marcos Portugal.

- Il barbiere di Siviglia (1816), an opera based on The Barber of Seville, with music by Gioachino Rossini.

- I due Figaro o sia Il soggetto di una commedia (1820), an opera based on the play Les deux Figaro ou Le sujet de comédie by Honoré-Antoine Richaud Martelly, with music by Michele Carafa.

- I due Figaro o sia Il soggetto di una commedia (1835), an opera based on the play Les deux Figaro ou Le sujet de comédie by Honoré-Antoine Richaud Martelly, with music by Saverio Mercadante.

- Chérubin (1905), an opera based on the character Chérubin, with music by Jules Massenet.

- Die Füchse im Weinberg (Proud Destiny, Waffen für Amerika, Foxes in the Vineyard) (1947/48), by Lion Feuchtwanger – a novel mainly about Beaumarchais and Benjamin Franklin.

- Beaumarchais (1950), a comedy written by Sacha Guitry.

- La mère coupable (1966), an opera based on The Guilty Mother, with music by Darius Milhaud.

- The Ghosts of Versailles (1991), an opera loosely based on La Mère coupable, with music by John Corigliano.

- Den brottsliga modern (1991), an opera based on La Mère coupable, with music by Inger Wikström.

- Beaumarchais l'insolent (1996), a film based on Sacha Guitry's play, directed by Édouard Molinaro.

- Beaumarchais, a six-episode radio series based on his life, broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 1996.

See also

In Spanish: Pierre-Augustin de Beaumarchais para niños

In Spanish: Pierre-Augustin de Beaumarchais para niños