Leo Sirota facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Leo Grigoryevich Sirota

|

|

|---|---|

| Лео Григорьевич Сирота | |

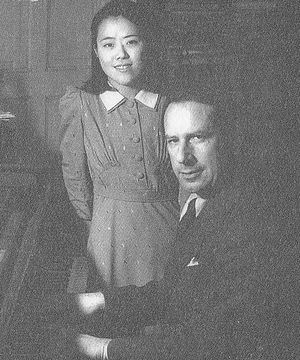

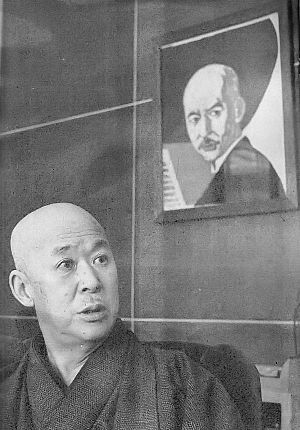

Publicity photo of Leo Sirota (circa 1941)

|

|

| Born | May 4, 1885 Kamenets-Podolsky, Podolia Governorate, Russian Empire (disputed)

|

| Died | February 25, 1965 (aged 79) New York City, US

|

| Resting place | Ferncliff Cemetery |

| Other names | Leiba Girshovich |

| Occupation | Pianist, teacher, conductor |

| Years active | 1893–1965 |

| Spouse(s) |

Augustine "Gisa" Horenstein

(m. 1920–1965) |

| Children | Beate Sirota Gordon |

| Relatives | Jascha Horenstein (brother-in-law) |

Leo Grigoryevich Sirota (born May 4, 1885 – died February 25, 1965) was a famous pianist and teacher. He was born in Russia but later became an American citizen. He was known for his amazing piano skills and for teaching many students around the world.

Contents

Who Was Leo Sirota?

Early Life and Musical Start

Leo Sirota was born in the Russian Empire. Some say he was born in Kamenets-Podolsky, while his daughter said he was born in Kiev. Both cities are now part of Ukraine. Leo was the fourth of five children in a middle-class Jewish family. His father owned a clothing store. All his brothers and sisters loved music. His brother Wiktor became a conductor, and Pyotr became a music agent.

Leo started learning piano at age 5 with a teacher named Michael Wexler. He quickly became very good at playing. His school often asked him to play for important visitors. In 1893, when he was 8, Leo played his first public concert. That same year, he joined the Imperial Music School of Kiev.

When he was 10, Leo went on his first tour in Russia. He even played for the famous pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Paderewski was so impressed that he invited Leo to study with him in Paris. However, Leo's mother thought he was too young to study in another country, so she said no. The next year, Leo started teaching piano himself. After finishing school, he went to the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. The head of the school, Alexander Glazunov, wrote a letter for Leo to study with Ferruccio Busoni in Vienna.

In 1899, Leo became a coach for singers at the Kiev Civic Opera. He also played for visiting singers, like Feodor Chaliapin.

Around 1900, there was a lot of violence against Jewish people in Russia. This made Leo think about moving away. His brothers had already moved to Warsaw and Paris. In 1904, Leo moved to Vienna, Austria.

Studying with Busoni in Vienna

In Vienna, Leo quickly became popular because of his talent and friendly personality. He met many important people in the music world. At first, he didn't use his letter to Busoni. Instead, he played for other famous pianists like Paderewski, Josef Hoffmann, and Leopold Godowsky. After that, he played for Busoni and chose him as his teacher. When Leo showed Busoni the letter from Glazunov, Busoni said, "Why do you need this? I've already heard you play!" While studying music, Leo also studied philosophy at the University of Vienna.

In 1905, Leo entered a piano competition in Paris, but he didn't win a prize. Other famous musicians like Béla Bartók and Wilhelm Backhaus were also in the competition. After the competition, Leo decided to stay in Vienna instead of going back to Russia.

Busoni thought Leo was one of his best students. He even dedicated some of his music to Leo. Once, after hearing Leo play a difficult piece by Franz Liszt, Busoni said, "After that masterful piece of playing, I don't wish to hear anyone else today." Leo was very proud that Busoni called him a "colleague."

In 1910, Busoni allowed Leo to play his own Piano Concerto for the first time in Vienna. This concert happened at the Great Hall of the Musikverein on December 13. Busoni himself conducted the orchestra. Many important people, including Arnold Schoenberg, were there. The concert was a huge success, and Busoni predicted a great future for Leo. News of Leo's success spread around the world. Busoni was also very kind to talented students who didn't have much money, teaching them for free.

World War I and New Connections

Later in 1910, Leo went back to Russia for another piano competition. There was a problem because a Russian law said Jewish people couldn't stay in St. Petersburg for more than 24 hours. Even though musicians asked the government to change the law, they refused. However, Leo was allowed to stay because he had earned the title of "Free Artist" after his studies in Russia. He didn't win a prize in this competition, but he became good friends with Arthur Rubinstein. Their friendship lasted their whole lives.

When World War I started in 1914, Leo's career was affected, even though he didn't have to join the army. He was still allowed to perform in public, even though he was from an enemy country.

During the war, Leo met Jascha Horenstein, another musician from Kiev. Horenstein started studying with Leo and invited him to play with an orchestra he organized. They became lifelong friends. Horenstein introduced Leo to his sister, Augustine, who was called Gisa. Gisa was so amazed by Leo's playing that she forgot to clap! She then started taking piano lessons from Leo. They fell in love, and Leo asked her to marry him. At first, she said no because she was already married and had a son.

Success and Family Life

When the war ended in 1918, it changed many things for Leo. He loved Russia, but he was sad about the October Revolution. He also didn't like that the old government in Austria had fallen. Despite these problems, Leo became a very successful international performer again. In 1919, he helped the singer Lotte Lehmann prepare for a new opera by Richard Strauss.

Leo stayed in touch with Gisa Horenstein, who still didn't want to divorce her husband. Busoni talked to Gisa and told her how wonderful Leo was. Finally, she agreed to a divorce and left her son with her husband. In 1920, Leo and Gisa got married. Busoni told Gisa, "You're married to a great artist. Please take good care of him." In 1923, their only daughter, Beate Sirota Gordon, was born. By the late 1920s, the Sirota family became citizens of Austria.

In 1921, Leo was invited to Berlin by Serge Koussevitzky to play concertos. His performances were a big hit with critics. One critic wrote that Leo's "virtuosity, passionate temperament, and engaging personality" had "literally taken Berlin by storm." Another called him a "master." Leo's success in Berlin led to concerts all over Europe. He played with famous conductors like Busoni, Koussevitzky, and Bruno Walter. Critics continued to praise him, with one saying his playing was like "Liszt resurrected from the dead."

Busoni's death in 1924 was a big shock to Leo. Leo also played new music and often performed modern piano pieces with his friend Eduard Steuermann.

In the 1920s, Leo started meeting more Soviet diplomats and musicians. In late 1926 and early 1927, he toured the Soviet Union, playing in Moscow and other cities. When he returned, he told a German newspaper that he had good feelings about his trip and would be happy to visit again. In 1928, he went on a second tour, this time with Egon Petri. The tour ended in Vladivostok, from where Leo began a solo tour of Manchuria.

First Trip to Japan

Leo arrived in Harbin, a city with many different communities, and stayed at the Modern Hotel.

It's not clear exactly how Leo ended up going to Japan from Manchuria. His daughter said that after a concert, a Japanese composer named Yamada Kōsaku visited him and offered him many concerts in Japan. Yamada remembered that Leo sent him a letter saying he planned to visit Japan. Either way, Leo's trip to Japan was not planned ahead of time. The Japanese music world was surprised by the arrival of such an important foreign musician.

Yamada quickly arranged a private concert for Leo on November 4, 1928. On November 15, Leo played his first public concert in Japan. Many people came to Tokyo's Asahi Hall, even though it was raining heavily. People were very excited because Leo's debut happened around the same time as the celebration of the new Emperor Shōwa.

Leo played 16 concerts in Japan. His last concert was on December 21 at the Nippon Seinenkan. For that concert, he chose to play a Yamaha piano, which was unusual for Western artists at the time. Yamaha used his choice in their advertisements, and he helped make Yamaha pianos popular. At the end of his tour, the Japanese newspapers called Leo a "god of the piano."

When Leo returned to Vienna, he told his family that Japan "went crazy" for him and treated him "as if he were a king." He believed Japan would become a "great country one day."

Leo also told his family that Yamada had offered him a teaching job at the Tokyo Music School. He would have enough time to schedule concerts as he wished. He started talking with his wife about moving to Japan permanently. Because of economic and political problems in Austria, Gisa suggested that Leo go on another six-month concert tour in Asia. The Sirotas packed their belongings and traveled from Vienna to Moscow, then took the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok.

Living in Japan Between Wars

On their way to Japan, Leo became friends with Kishi Kōichi, a composer. They would later play chamber music together. From Vladivostok, they sailed across the Sea of Japan to Yokohama. The whole journey took four weeks.

The worsening political situation in Europe, especially the rise of the Nazi Party, convinced the Sirotas to live in Japan permanently. They moved into a home in Akasaka, Tokyo, an area popular with foreigners. Their neighbors helped them get used to life in Japan. They also received support from Yamada and other important Japanese families. Throughout the 1930s, the Sirota home often hosted visiting musicians from Europe and the United States, including Jascha Heifetz and Joseph Szigeti.

In 1931, Leo became a professor of piano at the Tokyo Music School. He took over from another leading piano teacher. The school hoped that new teachers like Leo would help it become even better at training performers. Leo taught hundreds of Japanese students. Some of his best students were Sonoda Takahiro, Fujita Haruko, and Nagaoka Nobuko.

Leo was the most popular pianist in Japan before World War II. He performed and taught in big cities and in the countryside, where Western classical music was rarely heard live. He also often played as a soloist and with other musicians on the radio. From 1930 to 1931, a radio station broadcast all 32 of Beethoven's piano sonatas played by Leo. He was so famous that one of his concerts was mentioned in a famous Japanese novel.

In the 1930s, Leo often played chamber music with Kishi and other musicians. In 1931, Leo, along with a violinist and a cellist, formed the Sirota Trio. They performed at the Rokumeikan and became the most famous chamber music group in Japan at that time.

Leo lived comfortably in Japan and fit into its society. He was happy that there was very little anti-Jewish feeling in Japan in the early 1930s. His daughter later said, "I am quite certain that my dad was very happy in Japan."

Japan and Growing Tensions

In 1931, the Mukden Incident happened, which led to the Second Sino-Japanese War and later World War II. At first, these political events didn't affect the Sirota family. But as the 1930s went on, things changed. Leo's home was near an army base. When a military incident happened in 1936, soldiers stood guard in front of his house.

Early on, Japan treated Jewish residents the same as other foreign residents. Leo himself told European newspapers that Japan was "generous" to its Jewish residents and would "never discriminate against them." However, this started to change in March 1938 when Germany took over Austria. This meant Leo's Austrian citizenship became German. In November of that year, Japan and Germany signed a cultural agreement. Germany then put a lot of pressure on Japan to fire all Jewish musicians from official jobs. A German representative said it was "regrettable that music in Japan is dominated by the Jews." Japan was asked not to invite more Jewish people, except for "useful" ones like business people. At first, Japanese music schools and companies refused to fire Jewish staff or remove their recordings. Leo and other Jewish musicians continued to play and teach into the early 1940s.

Despite his good relationships, Leo and his family came under scrutiny. His daughter, who went to a German school in Tokyo, was bothered by staff because of her background. She even got low grades in 1936 because she said that a certain region should have stayed neutral instead of going back to Germany. Leo moved her to the American School the next year. This also made his daughter want to study in the United States. It was very hard for Leo to get permission for her to go, but his friends, including a diplomat, helped him.

In July 1941, Leo and his wife sailed on the Tatsuta Maru to visit their daughter, who was studying in California. On the ship, Leo met a former student who was now a diplomat. This student asked Leo to mail two letters for him once he arrived in the US. Later, the Japanese secret police found out about this. When Leo returned to Japan in November, he was arrested for spying. The charges were dropped after his student's father, who was a lawyer, helped him.

When the Tatsuta Maru neared San Francisco on July 24, the crew learned they couldn't dock because of tensions between the US and Japan. The ship stopped and turned around. The next morning, passengers realized they were far from shore. Some passengers started to panic. To help calm everyone, Leo played several unplanned concerts, which were reported in US newspapers. Finally, on July 30, the passengers were allowed to get off the ship in San Francisco.

During his visit to California, Leo met up with Erich Wolfgang Korngold, a composer he knew from Vienna. Korngold helped Leo and his family find a place to stay. Leo's wife and friends tried to convince him to stay in the United States, warning him that war with Japan was coming. Although a newspaper announced that Leo planned to settle in the US, his daughter said he refused. He had heard from Japanese officials that war was unlikely. He also felt he needed to honor his commitments to the Tokyo School of Music and his students.

That same month, he and his wife sailed for Japan, but they had to get off in Honolulu. The FBI noticed his German citizenship and told him to stay in Hawaii until he was cleared. In the meantime, Leo played concerts to pay for their stay. His first public performance in the US was at the Honolulu Academy of Arts on September 29. He continued playing concerts through October and early November, even in rural areas. His concert on October 31 was the first ever organized by the Maui Philharmonic Society. While in Maui, Leo and friends hiked to the top of Haleakalā.

Leo's concerts in Hawaii were very popular. A music critic wrote that Leo's piano playing reminded her of Paderewski and Arthur Rubinstein. Leo was also honored by Hawaiian officials.

Leo's last concert in Hawaii was on November 3. With help from the Tokyo Music School and the Japanese government, Leo and his wife left for Japan on November 5. Before he left, he thanked his Hawaiian hosts and said he believed there would be no war between the US and Japan. The Sirotas arrived in Yokohama on November 27. On December 7, the Japanese navy attacked Pearl Harbor.

Wartime and Later Years

On November 25, 1941, Germany took away the citizenship of all its Jewish citizens living outside the country. Leo, who was still on the ship, became stateless (meaning he had no country's citizenship). On December 8, Japan started watching its stateless residents closely. Some extreme nationalists disliked classical music because of the anger against the countries fighting Japan. However, the Japanese government still supported classical music. A naval officer even said, "Music is munitions" to show official policy. Because of this, Leo's musical activities increased during the first years of the war. Besides playing concerts and teaching, he also started sharing conducting duties with another musician at the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra.

After World War II, Leo moved to America and taught in St. Louis. A local radio station often asked him to play on air. Many of his recordings come from the tapes the studio gave him after these broadcasts. He knew a huge amount of music, including all of Chopin's works, which he broadcast. His playing was known for its beautiful sound and clear interpretations, along with amazing technique. His playing of a difficult Chopin piece was said to have amazed Arthur Rubinstein. Because his old recordings needed special work to sound good, people have only recently started to fully appreciate how great a pianist he was.

Leo Sirota died in 1965. His daughter was Beate Sirota Gordon.

Images for kids

-

Sirota became one of the favorite students of Ferruccio Busoni (in 1916)

-

The interior of the Great Hall of the Musikverein, where Sirota's "true debut" took place

-

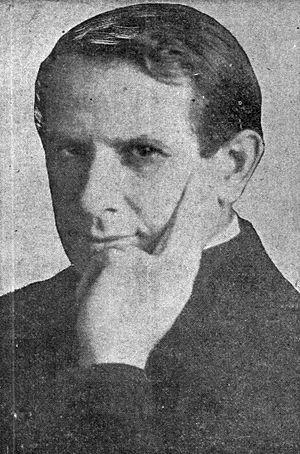

Arthur Rubinstein (in 1906) was a friend of Sirota and an admirer of his pianism

-

Sergei Koussevitzky's invitation to play in Berlin expanded Sirota's international career

-

Entrance to the Modern Hotel (circa 1930s) in Harbin, where Sirota stayed after his second Soviet tour

-

Yamada Kōsaku (in 1952) brought Sirota to Japan

-

Aerial view of Tokyo (circa 1930)

-

Sirota's recital on September 29, 1941, at the Honolulu Academy of Arts was his first performance on American territory

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |