Li Rui facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Li Rui

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

李锐

|

|||||||||

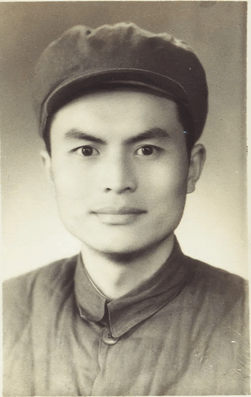

Studio portrait, 1947

|

|||||||||

| Member of the 12th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party | |||||||||

| In office 1982–1987 |

|||||||||

| Vice-Director of the Organisation Department of the Chinese Communist Party | |||||||||

| In office 1982–1984 |

|||||||||

| Vice-Minister of Water Resources | |||||||||

| In office 1958–1958 |

|||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||

| Born | 14 April 1917 Pingjiang County, Hunan, China |

||||||||

| Died | 16 February 2019 (aged 101) Beijing, China |

||||||||

| Resting place | Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery | ||||||||

| Political party | CCP | ||||||||

| Spouses |

|

||||||||

| Children | 3 | ||||||||

| Alma mater | Wuhan University | ||||||||

| Occupation | Revolutionary, politician, historian | ||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 李銳 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 李锐 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

Li Rui (simplified Chinese: 李锐; traditional Chinese: 李銳; pinyin: Lǐ Ruì; 14 April 1917 – 16 February 2019) was an important Chinese politician and historian. He was also known as a dissident, meaning he often disagreed with the government, even though he was a member of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

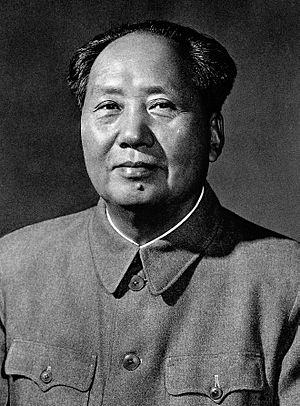

As a young student, Li joined the Communists in 1937 during the Chinese Civil War. By 1958, he became a vice-minister in charge of water resources. He spoke out against building the Three Gorges Dam, which caught the attention of Mao Zedong, the leader of the CCP. Mao was impressed and made Li his personal secretary. However, Li was an independent thinker and disagreed with Mao at a big meeting in 1959.

Because of his views, Li was removed from the party and sent to a prison camp. This started almost 20 years of being away from political power. He spent eight years alone in Qincheng Prison.

After Mao's death, Li was allowed back into the party. He got an important job but had to leave because he wouldn't give special treatment to the children of powerful party members. From the mid-1980s, Li wrote and spoke a lot, asking for freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and democracy. He also wrote five books about Mao and the early history of the Communist Party. Li stayed a party member until he died in 2019 at 101 years old. He was known for standing up against those who misused their power.

Contents

Li Rui's Early Life

Li Rui was born Li Housheng (李厚生) in Pingjiang County, Hunan Province, in April 1917. His family was wealthy. His father had been part of a group called the Tongmenghui, which worked to overthrow the old imperial rule. Li's father died when Li was only five years old.

As a high school student in Hubei, Li protested against local warlords. In 1934, he started studying mechanical engineering at Wuhan University. In 1935, he helped lead a student protest. They were upset that the Chinese government wasn't doing enough to stop Japan's actions against China.

Li Rui's Political Journey

Becoming a Young Communist Activist

Li secretly joined the Chinese Communist Party in February 1937. He was a very active member and was even jailed for a short time by the Republic of China's government for his communist activities. In the late 1930s, Li walked about 1,000 kilometers to reach the Communist base in Yan'an. His mother told him, "The Communists are good, but you might get killed."

From December 1939, he led the propaganda part of the party's youth committee. Li married his first wife, Fan Yuanzhen (范元甄), that same month. He became an editor for the Jiefang Daily (解放日报) newspaper in September 1941. He later became the head of the newspaper's editorial office in areas controlled by the Communists. He also worked as a secretary for Chen Yun, who later helped shape China's economic changes.

Li also helped start another newspaper, Qingqidui (轻骑队). This paper made fun of the Communist leaders. Because of this, he was put in prison from 1943 to 1944. During his time in prison, Li and his wife divorced briefly but remarried in June 1945. They had two daughters and one son.

In 1945, Li became a secretary to Gao Gang, a leader in the CCP's northeastern region. He held this job until 1947. In October 1952, after the Communists won the civil war, Li joined the Ministry of Water Resources. By 1958, he became its deputy head, making him the youngest vice-minister in China.

He caught the eye of China's leader, Mao Zedong, because he strongly opposed building the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. Mao invited Li to Beijing to discuss the issue. Mao was impressed by Li's passion and intelligence. Li was described as "blunt, brash, and quick-witted." Even though Li supported using water power, he warned that a large dam on the Yangtze would cost too much and cause many problems. He told Mao that the dam wouldn't solve flooding downstream because many large rivers flow into the Yangtze after the dam's planned location. Li successfully convinced Mao to delay the project.

Working for Mao, Then Prison and Exile

Mao hired Li as his personal secretary for industrial matters in 1958. However, Li soon began to criticize the Great Leap Forward, a big economic plan, and supported another leader named Peng Dehuai. At a meeting in Lushan in 1959, Li insisted on disagreeing with Mao. Li later said that Mao didn't care about the suffering caused by his policies. He felt Mao "put no value on human life."

Li was accused of working against Mao and was sent to a labor camp in Heilongjiang, near the border with the Soviet Union. He almost starved but was moved to a better camp by friends. He lost his Communist Party membership. Li was offered an early release if he would stop criticizing Mao, but he refused.

Released in 1961, Li returned to Beijing. After almost 22 years of marriage, his wife, Fan, spoke out against him and divorced him for good. Li was then sent to teach at a small school in the mountains, keeping him away from politics. One of his daughters, Li Nanyang (李南央), became distant from him after telling others about anti-Mao comments he made privately.

In 1966, Mao started the Cultural Revolution. Li was asked to speak out against his old colleagues who were Mao's private secretaries. He refused and was put in solitary confinement at the Qincheng Prison. Li stayed sane by writing poetry in the margins of Communist books, using iodine he took from the prison's medical supplies. Li was released in 1975 and sent back to teach at the same school in the mountains.

Returning to Power

After Mao's death in 1976 and the rise of Deng Xiaoping, Li got his CCP membership back. In 1979, he became a vice-minister in the Ministry of Electric Industry for three years. That same year, Li remarried Zhang Yuzhen (张玉珍).

In 1982, he was chosen to be part of the Central Committee for five years. In April of that year, he became vice director of the Organisation Department of the CCP. This was an important job that involved promoting, demoting, and hiring senior officials. In 1984, he had to resign from this role. This was because he refused to give special treatment to the children of powerful officials.

Li had strongly opposed the Three Gorges Dam earlier in his career. He continued to fight against its construction throughout the 1980s, working with environmentalist Dai Qing. Their efforts were not successful, and the dam was approved in 1992. Construction finished in 2006.

In 1989, Li personally saw the violent crackdown in Beijing during the Tiananmen Square protests. This made him even more opposed to the party's strict leaders. He was a supporter of reformers like Zhao Ziyang and Hu Yaobang.

Party Elder, Historian, and Dissident

After officially retiring in June 1995 at age 78, Li became known as an older, respected party member and a historian of Mao. He wrote five books about Mao's life. His writings openly criticized Mao and current party leaders.

Li was seen as a "veteran liberal member" of the CCP. He argued for free speech, freedom of the press, and democracy within a socialist system. In November 2004, the party's Propaganda Department banned Li from being published in the media. His books about Mao were censored and banned in Mainland China. His personal name, Rui (锐), means 'sharp' in Chinese, and he was known for being a challenge to the Communist Party's strict leaders. His views were secretly but officially called "subversive" (meaning they tried to undermine the government) in 2013.

Before every five-year Communist Party congress, Li wrote to other senior party members. He asked for political changes. At the 16th Party Congress in 2002, Li suggested changes to the Communist Party to the new leader, Hu Jintao. Li believed that having a constitution and more democracy would prevent the Communist Party from making big mistakes, like the Anti-Rightist Movement, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution.

In 2006, he was a main signer of an open letter criticizing the government for closing an investigative newspaper called Freezing Point (冰点). Before the 17th Communist Party Congress in 2007, Li and another retired academic wrote articles saying the Communist Party should become more like a European socialist party. The party's propaganda office criticized these comments. In October 2010, Li was the main signer of an open letter to the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress, asking for more press freedom. In 2017, he did not attend the 19th Party Congress. This was seen as a sign of his disagreement with leader Xi Jinping gaining more power.

Li had dedicated his life to the Communist Party and never thought about leaving it. When he was allowed back into the party in the 1970s, he hoped it had changed. But he was disappointed and later wrote about its "arrogance, ignorance, shamelessness, lawlessness."

Death and Funeral

As he got older, Li stayed mentally sharp. Even with his political views, he was allowed to keep his benefits as a senior CCP member. These included better medical care and his apartment in Minister's House, a building for respected retired party members.

Li died from organ failure in Beijing on 16 February 2019, at the age of 101. As an early and senior member of the Communist Party, Li was given a state funeral. He was buried at the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery, even though he wanted to be buried with his parents in his home province of Hunan. News of his death was limited by official censorship. His funeral was held with "secrecy and security." Despite the rules, hundreds of people came to the funeral, from regular citizens to his old colleagues and fellow revolutionaries. Even though he strongly disagreed with their policies, China's leaders, Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang, sent wreaths.

Li kept a diary every day from 1935 until 2018. This diary and Li's other papers were part of a lawsuit in 2019. Li's widow, Zhang, and his daughter, Li Nanyang, both claimed ownership of the diary. Zhang wanted it returned to China. The case was decided in favor of Li Nanyang, who had given the diary to the Hoover Institution in the American state of California.

Images for kids

-

Li's employer Mao Zedong (1893–1976) pictured in 1959

-

The completed Three Gorges Dam in 2006, which Li Rui opposed

See also

In Spanish: Li Rui para niños

In Spanish: Li Rui para niños