Hu Yaobang facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hu Yaobang

|

|

|---|---|

|

胡耀邦

|

|

Hu in 1986

|

|

| General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party | |

| In office 12 September 1982 – 15 January 1987 |

|

| Preceded by | Himself (as Chairman) |

| Succeeded by | Zhao Ziyang |

| Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party | |

| In office 29 June 1981 – 12 September 1982 |

|

| Deputy | Ye Jianying |

| Preceded by | Hua Guofeng |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as General Secretary) |

| Secretary-General of the Secretariat of the Chinese Communist Party | |

| In office 29 February 1980 – 12 September 1982 |

|

| Chairman | Hua Guofeng Himself |

| Preceded by | Deng Xiaoping (1966) |

| Succeeded by | Post abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 20 November 1915 Liuyang, Hunan, Republic of China |

| Died | 15 April 1989 (aged 73) Beijing, China |

| Resting place | Gongqingcheng, Jiujiang |

| Political party | Chinese Communist Party (1933–1989) |

| Spouse |

Li Zhao

(m. 1941–1989) |

| Relations | Hu Deping (eldest son) Hu Liu (second son) Hu Dehua (third son) Li Heng (daughter) |

|

Central institution membership

1980–1989: 11th, 12th, 13th Politburo Standing Committee

1980–1989: 11th, 12th, 13th Politburo 1980–1982: 11th Secretariat 1972–1989: 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, 12th, 13th Central Committee 1954–1989: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th 7th National People's Congress Other offices held

1978–1980: Head, Propaganda Department

1977–1978: Head, Organization Department 1964–1965: Party Committee Secretary, Shaanxi Province 1953–1978: First Secretary, Communist Youth League |

|

| Hu Yaobang | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Hu Yaobang" in Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 胡耀邦 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

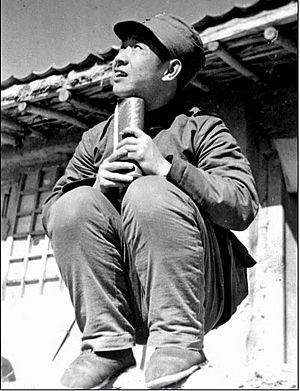

Hu Yaobang (Chinese: 胡耀邦; pinyin: Hú Yàobāng; 20 November 1915 – 15 April 1989) was an important leader in the People's Republic of China. He led the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which is the ruling party in China, from 1981 to 1987. First, he was the Chairman from 1981 to 1982, and then the General Secretary from 1982 to 1987. Hu joined the CCP in the 1930s and became well-known as a friend and colleague of Deng Xiaoping. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), a time of great political upheaval, Hu was removed from his positions, brought back, and then removed again by Mao Zedong. His burial place is in Gongqingcheng, a city near Jiujiang.

After Mao Zedong passed away, Deng Xiaoping became a very powerful leader. Hu Yaobang played a key role in a program called "Boluan Fanzheng", which aimed to correct mistakes made during the Cultural Revolution. Throughout the 1980s, Hu worked on many economic and political changes under Deng's guidance. However, these changes made some powerful older leaders in the Party, known as the Eight Elders, unhappy. They did not like the idea of free markets or Hu's government reforms. In 1987, when many student protests happened across China, Hu's opponents blamed him. They said his "laxness" and "bourgeois liberalization" (ideas seen as too Western) caused or worsened the protests. Because of this, Hu was forced to step down as Party General Secretary in 1987, but he was allowed to keep a seat in the Politburo, an important decision-making group.

Zhao Ziyang took over Hu's position as Party General Secretary and continued many of Hu's economic and political changes. When Hu died in 1989, a small group of people gathered to remember him and asked the government to change its view of his legacy. A week later, before Hu's funeral, about 100,000 students marched to Tiananmen Square. This event led to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. After these protests, the Chinese government did not allow much public discussion about Hu's life inside mainland China. However, in 2005, on the 90th anniversary of his birth, the government officially restored his good name and allowed his story to be told again.

Contents

Early Life and Revolution

Becoming a Young Revolutionary

Hu Yaobang's family came from Jiangxi and were Hakka people. They moved to Hunan during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), which is where Hu was born. Hu Yaobang grew up in a poor farming family and did not get much formal schooling. He never went to school as a child but taught himself to read. He took part in his first rebellion at age twelve. He left his family to join the Chinese Communist Party when he was only fourteen and became a full member in 1933. During the disagreements within the CCP in the 1930s, Hu supported Mao Zedong.

Hu was one of the youngest people to take part in the Long March, a famous journey by the Communist army. Before the Long March began, Mao Zedong's supporters were in danger, and Hu Yaobang was even sentenced to death. He was on his way to be executed, but a powerful local communist commander, Tan Yubao, saved his life at the last moment. Because Hu supported Mao, he was seen as someone who needed to be watched, so he was ordered to join the Long March.

Hu Yaobang was badly hurt in a battle near Zunyi. After he was wounded, the communist medical teams left him on the battlefield. But a childhood friend, a commander in the Chinese Red Army, happened to pass by. Hu called out his friend's nickname, and his friend helped him rejoin the army and get medical care.

In 1936, Hu joined a group led by Zhang Guotao. Their goal was to cross the Yellow River to expand the communist area west of Shaanxi and connect with forces from the Soviet Union or with a local leader in Xinjiang who was allied with the communists. However, Zhang Guotao's forces were defeated by local Nationalist leaders known as the Ma clique. Hu Yaobang and Qin Jiwei were among thousands captured by the Ma clique. Hu was one of only 1,500 prisoners who were made to work instead of being executed.

The Ma clique sent some of these prisoners to fight against the Japanese. Since their route passed near the communist base in Shaanxi, Hu Yaobang and Qin Jiwei planned a secret escape. The escape worked, and more than 1,300 of the 1,500 prisoners returned to Yan'an, the communist base. Mao Zedong himself welcomed them back, and Hu Yaobang stayed with the communist forces for the rest of his life.

In Yan'an, Hu attended the Anti-Japanese Military School. There, he met and married his wife, Li Zhao, who was also a student. After his training, Hu worked in the political department and was assigned to work with Peng Dehuai's army.

Hu became good friends with Deng Xiaoping in the 1930s and worked closely with him. In the 1940s, Hu worked under Deng as a political leader in the Second Field Army. During the final part of the Chinese Civil War, Hu went with Deng to Sichuan, where communist forces successfully took control of the province in 1949.

Early Political Career

In 1949, the CCP won the Chinese Civil War and founded the People's Republic of China. In 1952, Hu went with Deng to Beijing and became the leader of the Communist Youth League from 1952 to 1966. Hu quickly moved up in the Communist Party. However, in 1964, Mao sent Hu to work as the First Party Secretary of Shaanxi province, saying he "needs some practical training." Hu might have been sent away from Beijing because he wasn't seen as enthusiastic enough about Maoism, Mao's ideas. Unlike many others, Hu kept his membership in the Party Central Committee until 1969.

During the Cultural Revolution, Hu was removed from power twice and brought back twice, much like his mentor, Deng Xiaoping. In 1969, Hu was called back to Beijing to be punished. He became the "number one" of the "Three Hus," who were publicly shamed and paraded through Beijing. The other two "Hus" were Hu Keshi and Hu Qili, who were also important members of the Communist Youth League. After being publicly humiliated, Hu was sent to a work camp to participate in "reformation through labour," where he was forced to do hard physical work.

When Deng Xiaoping was temporarily brought back to Beijing from 1973 to 1976, Hu was also recalled. But when Deng was removed from power again in 1976, Hu was also removed and sent to herd cattle. Hu was brought back and restored to his positions a second time in 1977, shortly after Mao's death. After being recalled, he was promoted to lead the Party's organization department and later the Party's propaganda department. Hu was one of the main leaders responsible for reviewing the cases of people who had been punished during the Cultural Revolution. The Chinese government says Hu personally helped clear the names of over three million people. Hu quietly supported the 1978 Democracy Wall protesters, who were asking for more freedoms, and even invited two of them to his home. Hu disagreed with Hua Guofeng's "Two Whatevers" policy, which meant strictly following Mao's past decisions, and was a key supporter of Deng Xiaoping gaining power.

A Leader of Change

New Policies and Reforms

Hu Yaobang's rise to power was helped by Deng Xiaoping. Hu reached the highest levels of the Party after Deng became China's most powerful leader, known as the "paramount leader". In 1980, Hu became Party Secretary General and was elected to the powerful Politburo Standing Committee. In 1981, Hu became CCP Chairman. However, he helped get rid of the Party chairman position in 1982 to move China away from Mao's style of politics. Most of the chairman's duties were given to the General Secretary, a role Hu then took on. Deng's rise showed that the Party agreed China should move away from strict Maoist economics and try more practical policies. Hu led many of Deng's efforts to change the Chinese economy. By 1982, Hu was the second most powerful person in China, after Deng. In the last ten years of his career, Hu believed that educated people were essential for China to achieve the Four Modernizations (goals to improve agriculture, industry, defense, and science and technology).

In the early 1980s, Deng Xiaoping called Hu and Zhao Ziyang his "left and right hands." After becoming General Secretary, Hu introduced many political changes, often working with Zhao. The exact goals of Hu's changes were sometimes unclear. Hu tried to reform China's political system by:

- requiring candidates to be directly elected for the Politburo.

- holding more elections with multiple candidates.

- making the government more open.

- asking for public opinion before making Party policies.

- making government officials more directly responsible for their mistakes.

During his time in office, Hu worked to restore the reputations of people who had been unfairly treated during the Cultural Revolution. Many Chinese people consider this his most important achievement. He also supported a practical approach in the Tibet Autonomous Region after realizing that past policies had caused problems. After visiting Tibet in May 1980, he ordered thousands of Han Chinese officials to leave the region. He believed that Tibetans and Uyghurs should be able to manage their own affairs. Han Chinese who stayed were required to learn Tibetan and Uyghur languages. He set out six requirements to improve conditions, including increasing government funds for Tibet, improving education, and helping to revive Tibetan and Uyghur culture. Hu also apologized to Tibetans for China's past misrule in the region. He also announced the cancellation of soldier-farmers in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Hu traveled a lot during his time as General Secretary, visiting 1500 different districts and villages. He did this to check on local officials and stay connected with ordinary people. In 1971, he retraced the route of the Long March and used the chance to visit remote military bases in Tibet, Xinjiang, Yunnan, Qinghai, and Inner Mongolia.

Controversial Views

Hu was known for being open-minded and for speaking his mind, which sometimes bothered other senior Chinese leaders. During a trip to Inner Mongolia in 1984, Hu publicly suggested that Chinese people might start eating in a Western way (with forks and knives, on individual plates) to prevent diseases. He was one of the first Chinese officials to stop wearing a Mao suit and instead wear Western business suits. When asked which of Mao Zedong's ideas were good for modern China, he simply replied, "I think, none."

Hu was not ready to completely give up on Marxism, but he openly said that Communism could not solve "all of mankind's problems." Hu encouraged educated people to discuss sensitive topics in the media, such as democracy, human rights, and the idea of limiting the Communist Party's power in the government. Many older Party leaders did not trust Hu from the beginning and eventually became afraid of his influence.

Hu made serious efforts to improve relations between China and Japan, but he was criticized for doing too much. In 1984, when Beijing celebrated the twelfth anniversary of Japan recognizing the People's Republic, Hu invited 3,000 Japanese young people to Beijing. He arranged for them to visit Shanghai, Hangzhou, Nanjing, Wuhan, and Xi'an. Many senior officials thought Hu's efforts were too much, especially since Japan had only invited 500 Chinese youths the year before. Hu was also criticized for the expensive gifts he gave to visiting Japanese officials and for allowing his daughter to privately accompany Japanese Prime Minister Nakasone's son when they visited Beijing. Hu defended his actions by saying that strong relations with Japan were important and that the bad things Japan did in China during World War II were the actions of military leaders, not ordinary people.

Hu also upset some powerful people in the military when he suggested for two years in a row that China's defense budget should be cut. Senior military leaders began to criticize him. Military officials accused Hu of making bad choices when buying military equipment from Australia in 1985. When Hu visited Britain, military officials criticized him for drinking soup too loudly during a banquet hosted by Queen Elizabeth II.

Zhao and Hu started a big program to fight corruption. They allowed investigations into the children of high-ranking Party elders, who had grown up protected by their parents' power. Hu's investigations into these officials, sometimes called the "Crown Prince Party", made him unpopular with many powerful Party members. After Deng Xiaoping refused to support some of Hu's changes, Hu privately criticized Deng for being unsure and having "old-fashioned" ways of thinking. Deng eventually found out about these comments.

Forced to Resign

In December 1986, students organized public protests in over a dozen cities, asking for more political and economic freedom. The protests started at the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei, Anhui. They were led by a scientist named Fang Lizhi, who openly talked about political changes that would reduce the Communist Party's influence. Two other "radical intellectuals," Wang Ruowang and Liu Binyan, also led protests.

Deng Xiaoping did not like these three leaders and ordered Hu to remove them from the Party to silence them, but Hu Yaobang refused. In January 1987, after two weeks of student protests asking for more Western-style freedoms, a group of Party elders, senior military officials, and Deng Xiaoping forced Hu to resign. They said he had been too soft on student protesters and had moved too quickly towards free market-style economic changes.

After Hu was forced out, Deng Xiaoping promoted Zhao Ziyang to replace him as Party General Secretary. Hu officially resigned on 16 January but kept his seat in the Politburo Standing Committee. When Hu "resigned," the Party made him give a humiliating "self-criticism" where he admitted to "mistakes on major issues of political principles" and violating the Party's "collective leadership." During this event, which included all the Elders, Politburo, Secretariat, and Central Advisory Commission, all of Hu's allies abandoned him except for his close friend, Xi Zhongxun, who stood up and defended him. Hu had to calm Xi down, telling him, "Don't worry about it, Zhongxun, I've got this." After that, Hu became more private and less involved in Chinese politics. He spent his time studying history, practicing calligraphy, and taking long walks. After his resignation, Hu was generally seen as having no real power and was given mostly ceremonial roles.

Hu's "resignation" hurt the Communist Party's reputation but improved Hu's own. Among educated Chinese people, Hu became an example of someone who stood by his beliefs even when it was politically difficult, and who paid a price for it. The promotion of a conservative leader, Li Peng, to Premier after Hu left executive positions made the government less interested in reforms. This also disrupted plans for a smooth transfer of power from Deng Xiaoping to a leader like Hu.

Death, Protests, and Burial

His Death and Public Reaction

In October 1987, Hu kept his membership in the CCP's Central Committee and was later elected to the new Politburo. On 8 April 1989, Hu had a heart attack during a Politburo meeting in Zhongnanhai about education reform. He was rushed to the hospital with his wife. Hu passed away several days later, on 15 April, at 73 years old. His last wish was to be buried simply in his hometown.

In his official obituary, Hu was called "a long-tested and staunch communist warrior, a great proletarian revolutionist and statesman, an outstanding political leader for the Chinese army." Western reporters noted that Hu's obituary was very positive, likely to prevent suspicions that the Party had treated him badly. At the memorial service, Hu's widow, Li Zhao, blamed his death on how harshly the Party had treated him, telling Deng Xiaoping, "It's all because of you people!"

Even though he had been removed from real power for his "mistakes," public pressure forced the Chinese government to give him a state funeral, attended by Party leaders. The speech at Hu's funeral praised his work in bringing back political order and helping economic development after the Cultural Revolution. People lined up for 10 miles (16 km) to mourn Hu, which surprised China's leaders. Soon after his funeral, students in Beijing began asking the government to officially change its decision about Hu's "resignation" and to hold a more elaborate public funeral. The government then held a public memorial service for Hu in the Great Hall of the People.

On 22 April 1989, 50,000 students marched to Tiananmen Square to attend Hu's memorial service and deliver a letter to Premier Li Peng. Many people were unhappy with the Party's slow response and the relatively quiet funeral arrangements. Public mourning began in Beijing and other cities, centered around the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square. This mourning became a way for people to express anger about perceived favoritism in the government, Hu's unfair dismissal and early death, and the hidden power of "old men"—officially retired leaders like Deng Xiaoping who still held influence. These protests eventually grew into the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. Hu's ideas about freedom of speech and press greatly influenced the students taking part in the protests.

His Burial Place

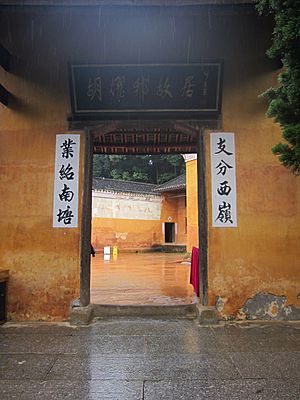

After Hu's funeral, his body was cremated, and his ashes were first buried in Babaoshan. Hu's wife, Li Zhao, was not happy with this location and successfully asked the government to move his remains to a better site. Eventually, Hu's remains were moved to a large mausoleum in Gongqingcheng (a city near Jiujiang), a city Hu had helped establish in 1955. Hu's mausoleum is considered one of the most impressive tombs for any senior Communist Party leader.

Li Zhao raised money for Hu's tomb from both private and public sources. With the help of her son, they chose a suitable location in Gongqingcheng. The tomb was built in the shape of a pyramid on top of a hill. On 5 December 1990, Hu's ashes were flown to Gongqingcheng, carried by his son, Hu Deping. The ceremony was attended by Wen Jiabao, many officials from Jiangxi, and 2,000 members of the Communist Youth League. Gongqingcheng's factories and schools were closed for the day, allowing 7,000 local citizens to attend. At the ceremony, Li Zhao gave a speech thanking the government and everyone who attended.

Official View and Recognition

Media Silence and Censorship

The Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 ended with force on 4 June 1989. Because Hu Yaobang's death had sparked the protests, the government decided that any public talk about Hu and his legacy could cause instability in China by restarting discussions about the political changes he supported. Due to his connection with the Tiananmen Square protests, Hu Yaobang's name became a forbidden topic in mainland China, and the Chinese government censored any mention of him in the media. For example, printed materials celebrating the anniversary of his death in 1994 were removed from publication.

Official Recognition

Hu Jintao announced plans to officially restore Hu Yaobang's good name in August 2005. Events were planned for 20 November, the 90th anniversary of Hu's birth. Ceremonies were held in Beijing, where Hu died, in Hunan, where he was born, and in Jiujiang, where he was buried. Some observers in the West thought that this move to recognize Hu Yaobang might be part of a larger effort by Hu Jintao to gain support from reform-minded colleagues who had always respected Hu Yaobang.

Some political experts believed that Hu Jintao's government wanted to be associated with Hu Yaobang. Both Hus (who were not related) rose to power through the Communist Youth League and were seen as part of the same "Youth League Clique." Hu Yaobang's support was partly responsible for Hu Jintao's quick promotions in the 1980s.

Some people thought that Hu Yaobang's recognition made it more likely that the Party would be willing to re-evaluate the 1989 Tiananmen protests, but others were doubtful. Memorials celebrating someone's birth or death often show political trends in China, with some hoping for further reforms. However, skeptics pointed out that Hu Jintao praised the governments of Cuba and North Korea shortly after announcing Hu Yaobang's public commemoration. This suggested it was unlikely the Party would pursue major political reforms soon.

On 18 November 2005, the Communist Party officially celebrated the 90th anniversary of Hu Yaobang's birth with activities at the People's Hall (the date was changed to two days earlier than planned). About 350 people attended, including Premier Wen Jiabao, Vice President Zeng Qinghong, and many other Party officials, famous people, and members of Hu Yaobang's family. It was rumored that Hu Jintao wanted to attend but was prevented by other senior Party members who still disliked Hu Yaobang. Wen was not given a chance to speak, and Zeng Qinghong was the most senior Party member to speak. In his speech, Zeng said that members should learn from Hu's good qualities, especially his honesty and genuine care for the Chinese people. Zeng stated that Hu had "contributed all his life and built immortal merits for the liberation and happiness of the Chinese people... His historic achievements and moral character will always be remembered by the Party and our people."

In the Media After 2005

An official three-volume biography and a collection of Hu's writings were planned for release in China. The project was started by a group of Hu's former assistants. When the government learned about it, they insisted on taking control. One of the main concerns for government censors was that details of Hu's relationship with Deng Xiaoping (especially about Hu's removal from power after he resisted orders to crack down on student protesters in 1987) would make Deng look bad. The authors of Hu's biography then refused offers from the government to release a censored version. Only one volume (covering events up to the end of the Cultural Revolution) of the biography written by Hu's former assistants was published; the other two volumes are still held by the government and remain unpublished.

Although magazines publishing articles about Hu were initially stopped, the ban was lifted in 2005, and these magazines were publicly released. Yanhuang Chunqiu, a magazine that supports reform, was allowed to publish a series of articles in 2005 celebrating Hu Yaobang's birthday. However, the government tried to limit how many copies were available. The issue celebrating Hu sold 50,000 copies, but the remaining 5,000 copies were destroyed by propaganda officials. This was the first time since his death that Hu's name appeared publicly.

In April 2010 (the 21st anniversary of Hu's death), Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao wrote an article in the People's Daily called "Recalling Hu Yaobang when I return to Xingyi." It was an essay about an investigation into the lives of ordinary people that Hu Yaobang and Wen Jiabao conducted in Xingyi County, Guizhou, in 1986. Wen, who worked with Hu from 1985 to 1987, praised Hu's "superior working style of being totally devoted to the suffering of the masses" and his "lofty morality and openness [of character]." Wen's essay caused a lot of excitement on Chinese websites, getting over 20,000 responses on Sina.com on the day it appeared. People familiar with the Chinese political system saw the article as Wen confirming that he was a protégé (a student or follower) of Hu.

On 20 November 2015, the 100th Anniversary of Hu Yaobang's birth, Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping held a major ceremony for Hu Yaobang in Beijing. Unlike the event ten years earlier, this 100th anniversary event was very public and attended by all members of the Politburo Standing Committee. Xi praised Hu for his achievements, saying that Hu "dedicated his life to the party and to the people. His led a glorious life, a life of struggle... his contributions will shine in history." Hu also appeared as a character in the 2015 historical drama Deng Xiaoping at History's Crossroads.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Hu Yaobang para niños

In Spanish: Hu Yaobang para niños

- Hu Yaobang's Former Residence

- Politics of the People's Republic of China

- History of the People's Republic of China

- Hu Deping, son of Hu Yaobang

- Zhang Zhixin