1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War, the Revolutions of 1989 and the Chinese democracy movement | |||

|

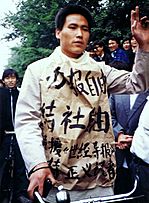

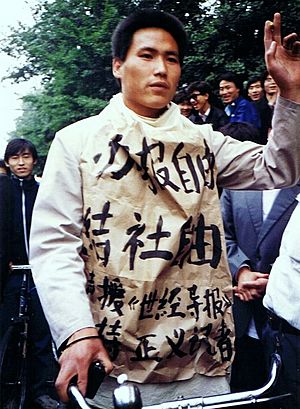

From top to bottom, left to right are people protesting near the Monument to the People's Heroes; Chinese tanks after the massacre outside of the United States Embassy; a burned vehicle in Zhongguancun Street in Beijing; Pu Zhiqiang, a student protester at Tiananmen; and a banner in support of the June Fourth Student Movement in Shanghai Fashion Store (formerly the Xianshi Company Building).

|

|||

| Date | 15 April 1989 – 4 June 1989 (1 month, 2 weeks and 6 days) |

||

| Location |

Beijing, China and 400 cities nationwide

Tiananmen Square 39°54′12″N 116°23′30″E / 39.90333°N 116.39167°E |

||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Goals | End of corruption within the Chinese Communist Party, as well as democratic reforms, freedom of the press, freedom of speech, freedom of association, social equality, democratic input on economic reforms | ||

| Methods | Hunger strike, sit-in, occupation of public square, rioting | ||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | No precise figures exist, estimates vary from hundreds to several thousands, both military and civilians (see death toll section) | ||

The Tiananmen Square protests were large demonstrations led by students in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, in 1989. These events are also known as the June Fourth Incident in China. During the Tiananmen Square Massacre, or June Fourth Clearing, soldiers with guns and tanks moved into Tiananmen Square. They fired at protesters and people trying to stop them.

The protests began on April 15 and ended on June 4. The government declared martial law and sent the army to take control of central Beijing. Many people were killed or hurt. Estimates of deaths range from hundreds to thousands. This big movement is sometimes called the 89 Democracy Movement.

The protests started after Hu Yaobang, a leader who wanted reforms, died in April 1989. China was changing fast with new economic policies. But people were worried about the future. There was a lot of inflation (prices going up) and corruption (dishonest actions by officials). Students wanted more honesty, freedom of the press, and freedom of speech. Workers were concerned about prices and their jobs. These groups came together to demand an end to corruption and better economic rules. At its peak, about one million people gathered in the square.

As the protests grew, government leaders disagreed on how to respond. Some wanted to talk, others wanted to use force. By May, students started a hunger strike. This made many people across China support them. Protests spread to about 400 cities. Premier Li Peng and other powerful leaders decided to use strong action. On May 20, the government declared martial law. They sent around 300,000 soldiers to Beijing. The soldiers moved into central Beijing in the early morning of June 4.

Countries around the world and human rights groups criticized the Chinese government for its actions. Western countries stopped selling weapons to China. The Chinese government arrested many protesters and their supporters. They also stopped other protests across China and controlled what the news could say. Officials who seemed to support the protests lost their jobs. These events stopped political reforms that had started in 1986. Remembering these protests is still a very sensitive topic in China today.

Understanding the Names of the Events

In China, people often name events by the month and day. So, the crackdown is called the "June Fourth Incident" (Chinese: 六四事件; pinyin: liùsì shìjiàn). This is like other big protests in Tiananmen Square, such as the May Fourth Movement of 1919. June Fourth refers to the day the army cleared the square. However, the military action actually started on the evening of June 3.

Other names like "June Fourth Movement" or "89 Democracy Movement" describe the entire period of protests.

The Chinese government has used different names for the event over time. At first, they called it a "counterrevolutionary riot." Later, they used more neutral terms like "political storm." Today, they usually call it "political turmoil between the Spring and Summer of 1989."

Outside mainland China, and among critics in China, it's often called the "June Fourth Massacre" or "June Fourth Crackdown." To avoid internet censorship in China, people online use other names like May 35th (May 31st + 4 days), VIIV (Roman numerals for 6 and 4), or 8964 (year and date).

In English, people use terms like "Tiananmen Square Massacre" or "Tiananmen Square Protests." But much of the violence happened outside the square, along a street called Chang'an Avenue. Also, protests happened in many other cities across China, not just Beijing.

Why the Protests Happened

China's Changes and Challenges

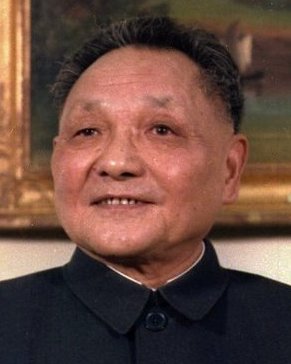

After Mao Zedong died in 1976, China started to change. The country was very poor. Deng Xiaoping became the leader and began big economic reforms. He wanted to make China richer. He put his allies, Zhao Ziyang and Hu Yaobang, in important government jobs.

These reforms helped many people, but they also caused new problems. There was a lot of corruption and favoritism among officials. Some people with powerful connections bought goods cheaply and sold them for high prices. This made many people angry. They felt that only democratic changes could fix these problems.

In 1988, the government tried to change how prices were set. This caused people to panic, withdraw money, and buy everything. Prices went up very fast. Many workers worried they couldn't afford basic goods. Also, state-owned businesses were cutting costs. This threatened the "iron rice bowl" system, which gave workers job security and benefits.

Students' Concerns and Political Ideas

Many students and thinkers felt that China's problems came from its strict political system. They believed that political reform was the answer. Small student groups formed on university campuses to discuss these ideas. They encouraged students to get involved in politics.

At the same time, the government's socialist ideas seemed less clear as China adopted more capitalist ways. Some people got rich quickly, which led to anger about unfair wealth. People wanted change, but the government still held all the power.

Leaders in the government had different ideas. Some, like Hu Yaobang, wanted more political freedom. Others, like Chen Yun, wanted more government control to keep things stable. Both sides needed the support of Deng Xiaoping, the most powerful leader.

Earlier Student Protests in 1986

In 1986, a professor named Fang Lizhi spoke about freedom and human rights at universities. His speeches spread widely. Many students felt that China's problems were due to its strict government.

In December 1986, students protested for faster reforms, democracy, and fair laws. These protests started in Hefei and spread to other big cities. Government leaders were worried. They blamed Hu Yaobang for being too "soft" on the students. Hu was forced to resign in January 1987. This made him very popular among students and intellectuals.

The Start of the 1989 Protests

Hu Yaobang's Death Sparks Action

When Hu Yaobang died suddenly on April 15, 1989, students were very upset. They believed his death was linked to his forced resignation. His death became a reason for students to gather. Posters appeared on campuses praising Hu and calling for his ideas to be honored. Soon, these posters talked about bigger issues like corruption and freedom.

Students began to gather at the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square. Thousands of students from Peking University and Tsinghua University joined. The gatherings grew into protests. Students wrote a list of demands for the government, called the Seven Demands. These included:

- Recognizing Hu Yaobang's ideas on democracy as correct.

- Admitting that past campaigns against certain ideas were wrong.

- Sharing information about leaders' family incomes.

- Allowing private newspapers and stopping news censorship.

- Increasing money for education and raising teachers' pay.

- Ending limits on protests in Beijing.

- Having fair news coverage of students.

On April 18, students stayed in the square. Some gathered at the Great Hall of the People. Others went to Xinhua Gate, where the party leaders worked. They demanded to talk with the government. Police tried to make them leave.

The Government's Strong Warning

On April 20, a group of workers called the Beijing Workers' Autonomous Federation also spoke out against the government.

Hu Yaobang's funeral was on April 22. About 100,000 students marched to Tiananmen Square, even though they were told not to. The funeral was broadcast live. Students were emotional. Three students knelt on the steps of the Great Hall to give a petition to Premier Li Peng. But no leaders came out to speak with them. This made the students angry. Some called for a boycott of classes.

On April 23, students formed the Beijing Students' Autonomous Federation. They called for all Beijing universities to boycott classes. The government was worried about this independent group.

On April 22, riots broke out in Xi'an and Changsha. In Xi'an, cars were burned and shops were looted. In Changsha, stores were robbed. Over 350 people were arrested. In Wuhan, students protested the local government. General Secretary Zhao Ziyang wanted to talk with students and stop the riots. But Premier Li Peng wanted stronger action. Zhao left for a trip to North Korea on April 23.

The April 26 Editorial

While Zhao was away, Li Peng was in charge. On April 24, Li Peng and other leaders met with Beijing officials. The officials said the protests were a plot to overthrow the government. Li Peng and President Yang Shangkun met with Deng Xiaoping. Deng agreed that strong action was needed.

On April 26, the official newspaper People's Daily published an article called "It is necessary to take a clear-cut stand against disturbances." This article said the student movement was against the party and government. It reminded people of past troubles. This made students very angry. Instead of stopping them, the article made them more determined to protest.

Big Protests on April 27

On April 27, 50,000 to 100,000 students marched through Beijing to Tiananmen Square. They broke through police lines. Many factory workers and other citizens supported them. Student leaders wanted to show their patriotism. They used slogans against corruption, not against the Communist Party itself.

The success of this march made the government offer to meet with student representatives. On April 29, a government spokesman met with student groups. But independent student leaders refused to attend.

When Zhao Ziyang returned from North Korea on April 30, he took charge again. He believed a tough approach was not working. He allowed the press to report positively on the movement. In speeches on May 3-4, Zhao said students' concerns were fair and their movement was patriotic. This went against the April 26 Editorial. Many students were happy with this. By May 4, most Beijing universities ended their class boycotts.

Protests Grow Stronger

Planning for Talks

The government was divided on how to handle the protests. Zhao Ziyang wanted to talk with students. Li Peng wanted a tough approach. They argued in a meeting on May 1. Zhao pushed for more talks.

Student leaders chose representatives for formal talks. But some leaders, like Wang Dan and Wu'erkaixi, didn't trust the government. They thought talks were just a trick. They wanted to use stronger tactics. They decided to start a hunger strike on May 13. At first, not many joined, until Chai Ling made an emotional speech.

The Hunger Strikes Begin

Students began their hunger strike on May 13. This was two days before Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was set to visit China. Student leaders hoped the hunger strike would force the government to meet their demands. The hunger strike gained a lot of public sympathy. By May 13 afternoon, about 300,000 people were in the square.

Protests and strikes also started at universities in other cities. Many students traveled to Beijing to join. The Tiananmen Square protest was usually orderly. Students marched daily, singing patriotic songs.

Deng Xiaoping ordered the square to be cleared for Gorbachev's visit. Zhao Ziyang tried to negotiate with students. He believed students would not want to embarrass the country during a big international event. On May 13, a government official met with student leaders. He said the welcoming ceremony for Gorbachev would be moved, whether students left or not. This confused the student leaders.

Gorbachev's Visit and Government Embarrassment

News reporting became more open in early May. State media showed sympathy for the protesters. On May 14, thinkers got permission to share their views in a newspaper. They urged students to leave the square. But many students thought these thinkers were speaking for the government and refused to move.

Formal talks happened between government and student representatives. The government official said the student movement was patriotic. He asked students to leave the square. But the meeting became chaotic. Student leaders had different demands. The meeting ended without much progress.

Students stayed in the square during Gorbachev's visit. His welcoming ceremony had to be held at the airport. This was a big embarrassment for China's leaders on the world stage. It made many moderate government officials lean towards a tougher approach.

When Gorbachev met with Zhao Ziyang on May 16, Zhao told him that Deng Xiaoping was still the "paramount authority" in China. Deng felt this was Zhao trying to blame him for the protests. This statement caused a big split between China's two most senior leaders.

Support Grows Across China

The hunger strike made many people support the students. About a million Beijing residents, including soldiers, police, and government workers, showed their support on May 17-18. Even some official groups encouraged their members to protest. The Red Cross Society of China sent medical help to the hunger strikers. Many foreign journalists stayed in Beijing, showing the protests to the world.

The movement, which had slowed down, now gained new strength. By May 17, protests were happening in about 400 cities across China. Local governments didn't know how to respond. The government's authority seemed to weaken as the hunger strikers gained sympathy. This put huge pressure on the leaders to act.

On May 17, leaders met at Deng Xiaoping's home. Zhao Ziyang's soft approach was criticized. Li Peng and others said Zhao had made the students bolder. Deng warned that they could not back down. He decided to send troops to Beijing and declare martial law. He said the protesters were trying to overthrow the government. Zhao Ziyang and another leader, Hu Qili, opposed martial law. But Li Peng and others supported it. Deng appointed the supporters to carry out the decision.

On the evening of May 17, Zhao announced he was ready to "take leave" because he could not bring himself to carry out martial law.

Li Peng met with students on May 18. Students again demanded that the government change its view of the protests. Li Peng said the government's main concern was getting hunger strikers to hospitals. The talks were tense and didn't achieve much. But student leaders were seen on national television. Some protesters started calling for the overthrow of Li Peng and Deng.

In the early morning of May 19, Zhao Ziyang went to Tiananmen Square. He spoke to the students, urging them to end the hunger strike. He told them they were young and should not sacrifice their futures. This was his last public appearance.

On May 19, leaders met with military officials. Deng said martial law was the only choice. He decided to remove Zhao from his position.

Watching the Protesters

The government watched student leaders closely. They used cameras and listened to phone calls to find out who was involved. After the military action, the government questioned many people to find out who had been at the protests.

Protests Outside Beijing

Students in Shanghai also protested after Hu Yaobang's death. The city's party leader, Jiang Zemin, spoke to them calmly. But he also quickly sent police to control the streets. He removed party leaders who supported the students.

On April 19, a magazine tried to publish an article supporting the Beijing students. Jiang Zemin ordered it censored. This action earned him trust from conservative leaders.

On May 27, over 300,000 people in Hong Kong gathered to support the students. The next day, 1.5 million people marched in Hong Kong. People around the world, especially Chinese communities, also protested. Many governments warned against traveling to China.

Military Action

Martial Law Declared

The Chinese government declared martial law on May 20. They sent at least 30 army divisions from different parts of the country. About 250,000 soldiers were sent to Beijing.

Protesters blocked the army's entry into the city. Tens of thousands surrounded military vehicles. They talked to soldiers and gave them food and water. The army was ordered to withdraw on May 24. This seemed like a win for the protesters. But in reality, the army was preparing for a final move.

Meanwhile, students in the square became disorganized. There was no clear leadership. The square was overcrowded and dirty. Some student leaders wanted to leave the square and regroup. But others wanted to stay. There were arguments over who was in charge.

June 1-3: Final Preparations

On June 1, Li Peng wrote a report saying the protests were a "counterrevolutionary riot." He said military action was needed. The report claimed protesters were terrorists. Another report said Western countries were trying to overthrow the Communist Party. This made leaders feel that military action was justified.

On June 2, protests broke out again. Students were angry at news articles telling them to leave the square. Three thinkers and a singer started a second hunger strike to revive the movement.

On June 2, Deng Xiaoping and other leaders met. They agreed to clear the square peacefully if possible. But if protesters didn't cooperate, troops could use force. Newspapers reported that troops were in ten key areas. Soldiers were secretly moved into buildings near the square.

On the evening of June 2, student leaders told people to set up roadblocks to stop troops.

On the morning of June 3, students saw soldiers in plain clothes trying to bring weapons into the city. Students seized the weapons and gave them to police. Protesters clashed with police and soldiers near Zhongnanhai, the party leadership's compound.

At 4:30 PM on June 3, leaders finalized the order for martial law enforcement:

- The operation would start at 9 PM.

- Troops must reach the square by 1 AM on June 4 and clear it by 6 AM.

- No delays were allowed.

- Troops could use any means to clear obstacles.

- State media would warn citizens.

The order didn't say "shoot to kill," but "use any means" was understood by some as permission to use deadly force. Leaders watched the operation from government buildings.

June 3-4: Clearing the Square

On the evening of June 3, state TV warned people to stay indoors. But crowds went to the streets to block the army. Army units advanced on Beijing from all directions.

Violence on Chang'an Avenue

Around 10 PM, the 38th Army fired warning shots into the air as they moved east. This didn't scare the crowds. Their advance was stopped by burning buses and barricades. Crowds tried to stop the military. As the army moved forward, people were killed along Chang'an Avenue. The most deaths happened between Muxidi and Xidan. Many military vehicles were destroyed or damaged.

To the south, other army units also used live ammunition. People were killed in several areas.

Protesters Attack Soldiers

Some student leaders, like Chai Ling, seemed to think a violent clash was needed for China to understand the movement's importance.

The Wall Street Journal reported on June 5, 1989, that angry crowds attacked soldiers and tanks, shouting "Fascists!"

Clearing Tiananmen Square Itself

At 8:30 PM, army helicopters appeared over the square. Students called for more people to join them. At 10 PM, the Tiananmen Democracy University was founded at the base of the Goddess of Democracy statue. A student leader urged everyone to stay united and non-violent. At 12:30 AM, there were still 70,000-80,000 people in the square.

Around 1:30 AM, army units arrived and sealed off the square. Soldiers surrounded the remaining students at the Monument of the People's Heroes. Students broadcast messages asking the troops to be peaceful.

Around 2:30 AM, some workers with a captured machine gun wanted revenge. A singer, Hou Dejian, persuaded them to give up the weapon. At 3:30 AM, Hou Dejian and others agreed to negotiate with soldiers. They asked for safe passage for students to leave. The army agreed.

At 4 AM, the lights in the square turned off. A loudspeaker announced that the square would be cleared. Students sang The Internationale. Hou Dejian told student leaders about the agreement. At 4:30 AM, the lights came back on. Troops advanced on the monument. At 4:32 AM, Hou Dejian told the crowd about the talks. Many students were angry.

Around 4:35 AM, soldiers charged the monument and shot out the students' loudspeaker. Other troops smashed cameras. An officer told students to leave. Some students and professors convinced others to leave. Witnesses heard gunshots.

Around 5:10 AM, students began to leave the monument. They linked arms and marched out. Soldiers were then ordered to clear all debris from the square. The square was closed to the public for two weeks.

Later that morning, thousands of people tried to re-enter the square from the east. Soldiers blocked them and opened fire. People fled in panic. An ambulance was also caught in the gunfire.

June 5 and the Tank Man

On June 5, a famous image was captured: a lone man standing in front of a line of tanks leaving Tiananmen Square. This "Tank Man" became a symbol of the protests. He stood in the tank's path, then climbed onto the lead tank to talk to the soldiers. He was later pulled away by a group of people. His identity and fate are still unknown.

The government regained control in the week after the military action. Officials who supported the protests were removed. Protest leaders were arrested.

Protests Outside Beijing After June 4

After Beijing was controlled on June 4, protests continued in about 80 other Chinese cities. In Hong Kong, people wore black to show support.

In Shanghai, students marched and blocked roads on June 5. Train traffic was stopped. Factory workers went on strike. The city government cleared the blockades without deadly force. Shanghai's leaders were praised for avoiding major violence.

In other cities like Xi'an, Wuhan, and Nanjing, students continued protests. They blocked roads and train lines. In Wuhan, people started taking money out of banks and panic-buying.

In Nanjing, students blocked bridges. They were persuaded to leave but returned the next day.

Government's Statements

On June 6, a government spokesman said that "nearly 300 people died," including soldiers, 23 students, and others. He said 5,000 police and soldiers and over 2,000 civilians were wounded. A military spokesman said no one was killed in Tiananmen Square itself, and no one was run over by tanks in the square.

On June 9, Deng Xiaoping appeared in public. He praised the soldiers who died. Deng said the student movement wanted to overthrow the party and create a Western-style country. He argued that protesters used complaints about corruption to hide their real goal of changing the socialist system.

What Happened Next

Arrests and Escapes

On June 13, 1989, the Beijing police ordered the arrest of 21 student leaders. Their faces and descriptions were shown on TV. This list has never been officially removed by the Chinese government.

Only 7 of the 21 leaders managed to escape. Some, like Chai Ling and Wu'erkaixi, went to Western countries. This was helped by "Operation Yellowbird", a secret effort to help dissidents leave China. Those who escaped generally cannot return to China today.

Other student leaders were arrested and jailed. Some, like Chen Ziming and Wang Juntao, were accused of being the "black hands" behind the movement. They were sentenced to 13 years in prison. Some people on the list have disappeared.

As of May 2012, at least two people were still in prison for protest-related activities. In June 2014, it was believed that Miao Deshun was the last known prisoner from the protests.

Changes in Leadership

The party removed Zhao Ziyang from his leadership position. Hu Qili, who also opposed martial law, was removed but kept his party membership. Other reform-minded leaders were also moved to less powerful roles.

Jiang Zemin, the party leader of Shanghai, was promoted to the top position of General Secretary. His actions in Shanghai, where he avoided deadly violence, gained him support. Deng Xiaoping himself stepped down from his last official leadership role later that year.

The party also began a program to remove officials who sympathized with the protesters. Millions of people were investigated. Tens of thousands were arrested, jailed, or sent to labor camps.

News Coverage

Official Story

The Chinese government says that using force on June 4 was necessary to control "political turmoil." They say it brought stability needed for economic growth. Chinese leaders continue to repeat this official story.

The government controls what is said about the Tiananmen Square protests. News media must follow the official account. In 2001, secret government files about the events, known as the "Tiananmen Papers", were published overseas. In 2019, a Chinese general said the government's actions were "necessary and correct."

Chinese Media

The events of June 4 ended a time of more press freedom in China. News workers faced strict rules and punishment. News anchors who showed sympathy for protesters were fired. Editors and staff at the People's Daily were also removed or arrested.

Foreign Media

When martial law was declared, the Chinese government cut off satellite broadcasts from Western news channels. Journalists tried to report by phone. Video footage was smuggled out of the country. Some foreign journalists were harassed or expelled.

Reactions Around the World

The Chinese government's actions were widely condemned by Western governments and media. Countries in Europe, North America, and Australia criticized China. However, many Asian countries remained silent. India's government ordered minimal news coverage to protect relations with China. Some communist countries, like Cuba and East Germany, supported the Chinese government.

Long-Term Effects

Politics in China

The protests led to the party having stronger control over China. Many freedoms from the 1980s were taken away. The party regained firm control over news and media.

Before 1989, China tried to separate the powers of different leaders. But during the protests, President Yang Shangkun used his power to support military action against the General Secretary. This showed how power could be mixed up. By 1993, the top positions (General Secretary, military chairman, and President) were held by the same person. This practice continues today.

Before 1989, the Chinese military and police did not have much riot control gear. After the protests, police in Chinese cities were given non-deadly equipment like rubber bullets and tear gas. The government also spent more money on internal security.

Restrictions on freedoms were slowly loosened after a few years. Private newspapers grew. TV stations challenged state-run TV. The government also started to focus on nationalism as an idea, rather than just communism. This helped the party gain public support. For example, when the US bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in 1999, many Chinese people supported the party.

Economy

After the protests, many experts thought China's economy would suffer. The violent response delayed China joining the World Trade Organization until 2001. Aid and loans to China decreased. Tourism dropped. Foreign investments were canceled.

However, the government quickly tried to regain control of the economy. Deng Xiaoping, even after retiring, pushed for more economic reforms in 1992. By the mid-1990s, China was opening its markets even more than before. The economic impact of the 1989 events was temporary. Many people who had wanted political change now focused on economic activities. The economy grew quickly in the 1990s.

Hong Kong's Future

In Hong Kong, the Tiananmen Square protests caused fears about China's promises for Hong Kong's future after it returned to Chinese rule in 1997. Many Hong Kong people lost trust in the Beijing government. This led to many Hong Kongers moving to Western countries before 1997.

Large candlelight vigils have been held in Hong Kong every year since 1989 to remember the events. The June 4th Museum in Hong Kong closed in 2016, but efforts are being made to reopen it. A virtual version of the museum was blocked online in 2021.

The events of 1989 are still very important in Hong Kong. They influence how people view China and democracy. A monument called the Pillar of Shame was placed at the University of Hong Kong in 1997. It was removed by university officials in December 2021.

China's Image Around the World

The Chinese government was widely criticized for its actions. China became somewhat isolated internationally. But Deng Xiaoping wanted to continue economic reforms. China worked to change its image from a strict government to a global economic partner.

The crackdown had little effect on China's relations with its Asian neighbors. These countries often had similar human rights records and understood China's situation. China also improved relations with Russia and other countries.

China joined more international organizations. It signed treaties on nuclear weapons and chemical weapons. China also became a provider of aid to other countries, not just a receiver.

The government promoted China as a good place for investment. Many world leaders believed that by doing business with China, political reforms would follow. This led many companies to focus on business rather than politics or human rights.

Arms Embargoes

The European Union and the United States stopped selling weapons to China because of the Tiananmen Square protests. This ban is still in place today. China has asked for the ban to be lifted, with some support from European countries. But concerns about China's actions towards Taiwan have stopped these efforts. The European Parliament has always opposed lifting the ban.

The arms embargo has limited China's options for buying military equipment. China has had to look for weapons from other sources, like former Soviet countries.

Current Issues

Censorship in China Today

The Chinese government still forbids discussions about the Tiananmen Square protests. They block and censor information to suppress public memory of the events. Textbooks have little or no information about them. After the protests, many books, films, and newspapers were banned or shut down.

Access to information about the protests online is restricted or blocked. Websites that support the overseas Chinese democracy movement are blocked. Censorship is stricter for Chinese-language sites. Social media censorship is very strict around the anniversary of the massacre. Even indirect references are censored.

Many young people born after 1980 don't know about the events. Some older thinkers no longer try to bring political change. Some former political prisoners don't talk to their children about their involvement, fearing it could put them at risk.

While public discussions are taboo, private discussions still happen. People who speak out, like Liu Xiaobo and the Tiananmen Mothers, face surveillance or harassment. Security forces are deployed every year on June 4 to prevent public remembrance. Journalists are often denied entry to the square. Internet searches for "June 4 Tiananmen Square" in China are censored.

Calls for Reassessment

The party's official stance is that the use of force was necessary for stability and economic growth. Chinese leaders continue to repeat this.

Some Chinese citizens have called for the government to re-evaluate the protests and pay victims' families. The Tiananmen Mothers group seeks compensation and justice for victims. A former soldier involved in the crackdown wrote an open letter asking for a re-evaluation. He was arrested.

In 2006, the government made a payment to a victim's mother. This was called "hardship assistance." It was the first public case of the government helping a victim's family. Some saw this as a way to keep social stability, not a change in the official stance.

Leaders Expressing Regret

Before he died in 1998, Yang Shangkun reportedly said that June 4 was the Communist Party's biggest mistake. He believed it would eventually be corrected. Zhao Ziyang remained under house arrest until his death in 2005. His aide has called for the government to change its view. Chen Xitong, the mayor of Beijing at the time, expressed regret for the deaths of innocent people in 2012. Premier Wen Jiabao reportedly suggested reversing the government's position in party meetings, but his ideas were rejected.

United Nations Report

In 2008, the UN Committee Against Torture expressed concern about the lack of investigations into deaths, arrests, or disappearances from June 4, 1989. It said the Chinese government had not told families what happened to their loved ones. It also noted that those who used excessive force had not been punished. The Committee recommended that China apologize, pay reparations, and prosecute those responsible.

In December 2009, the Chinese government responded. It said the case was closed and that its actions were "necessary and correct." It called observations that labeled the event a "Democracy Movement" a "distortion."

Images for kids

-

Mourning banners hung near the South Gate of Beijing University taken a few days after the crackdown.

See also

In Spanish: Protestas de la plaza de Tiananmén de 1989 para niños

In Spanish: Protestas de la plaza de Tiananmén de 1989 para niños

- Censorship in China

- Tank Man

- Human rights in China

- Protest and dissent in China

- Student protests in China

- Tiananmen Square

- Chinese democracy movements

- Deng Xiaoping

- Revolutions of 1989

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |