Peng Dehuai facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Yuanshuai

Peng Dehuai

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

彭德怀

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Peng in his Marshal uniform, 1955

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Minister of National Defense | |||||||||||||||||||

| In office September 28, 1954 – September 17, 1959 |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Zhou Enlai | ||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Lin Biao | ||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

彭清宗 (Péng Qīngzōng)

October 24, 1898 Shixiang, Xiangtan County, Hunan, Qing Empire |

||||||||||||||||||

| Died | November 29, 1974 (aged 76) Beijing, People's Republic of China |

||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | CCP (1928–1959) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Hunan Military Academy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Nicknames |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | Chinese Communist Party | ||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1916–1959 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rank |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Commands |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Awards |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 彭德怀 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 彭德懷 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Peng Dehuai (October 24, 1898 – November 29, 1974) was a very important Chinese general. He served as China's Minister of National Defense from 1954 to 1959. Peng grew up in a poor family and had to stop school at age ten to work.

When he was sixteen, Peng became a soldier. For the next ten years, he served in different armies in Hunan province, rising from a low rank to major. In 1926, his forces joined the Kuomintang (KMT), a major political party. This is when Peng first learned about communism. He fought in the Northern Expedition, a campaign to unite China. Later, he joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and became a close ally of Mao Zedong and Zhu De.

Peng was a top general who defended the Jiangxi Soviet, a communist base, from KMT attacks. He also took part in the Long March, a famous journey by the communists. During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), Peng wanted to work with the KMT to fight Japan. He led a large communist attack called the Hundred Regiments Offensive. After Japan surrendered, Peng commanded communist forces in Northwest China. He protected Mao Zedong and helped bring a large area, including Xinjiang, into the new People's Republic of China.

Peng was one of the few military leaders who supported China joining the Korean War (1950–1953). He led the Chinese People's Volunteer Army in Korea. His experiences made him believe China's military needed to be more professional and modern. He tried to reform the army based on the Soviet model. Peng also disagreed with Mao Zedong's growing power and economic policies like the Great Leap Forward, which caused a huge famine. This led to a big disagreement at the 1959 Lushan Conference. Mao won this argument, and Peng was removed from his important jobs.

Peng lived quietly until 1965, when he was given a small role in government again. However, during the Cultural Revolution in 1966, he was arrested and publicly criticized. He was treated very harshly and died in prison in 1974. After Mao died, Peng's old friend Deng Xiaoping became China's leader. Deng worked to clear the names of those who were unfairly treated during the Cultural Revolution. Peng was one of the first to be officially honored again in 1978. Today, Peng is seen as one of the most respected generals in China's history.

Contents

Early Life and First Steps

Peng was born on October 24, 1898, in a small village in Hunan province. His family was poor, living in a simple hut and farming a small piece of land. His father also ran a shop. They were a large family of eight people.

Peng's grand-uncle had fought in the Taiping rebellion. He often told Peng about the old ideals: everyone should have enough food, and land should be shared fairly. Peng later described his family as "lower-middle peasant."

Peng went to primary school for a few years. But in 1908, when he was ten, his family's money problems forced him to leave school. There was a severe drought, and his mother and a baby brother died of hunger. His father had to sell most of their belongings. Peng and his brothers had to beg for food. For two years, Peng worked looking after water buffaloes.

In 1911, Peng left home and worked in a coal mine. He pushed coal carts for a small wage. In 1912, the mine went out of business, and Peng lost half his pay. He returned home and did odd jobs. In 1913, another drought hit Hunan. Peng joined a protest that led to people taking grain from a merchant's storehouse and sharing it. Police wanted to arrest Peng, so he fled. He worked for two years building a dam. In 1916, he returned home and joined the army.

Joining the Military

Peng joined the army in March 1916, at age 17. He was a private second class soldier. He sent part of his monthly pay to his family. Within seven months, he was promoted to private first class. One of his officers, a Nationalist, inspired Peng to support social reform and national unity.

In 1917, a civil war broke out. Peng's group joined forces with those who supported Sun Yat-sen. Peng learned about military tactics and classical Chinese writing. In 1918, he was captured but released after two weeks. By 1919, he was a master sergeant. His forces helped capture the provincial capital, Changsha, in 1920.

Peng was promoted to second lieutenant in 1921. He became an acting company commander. In one village, he saw a landlord mistreating the poor. Peng ordered his soldiers to arrest and execute the landlord. He was criticized but not punished. This made Peng think about leaving the local army. In 1922, he traveled to Guangdong to find work with the Kuomintang army, but he didn't like what he saw. He returned home, planning to be a farmer.

However, farming wasn't for him. A friend suggested he apply to the Hunan Military Academy. Peng was accepted in August 1922 and used the name "Dehuai" for the first time. He graduated in August 1923 and rejoined his old group as a captain. He was promoted to acting battalion commander in 1924.

In 1925, Peng began to organize his battalion along pro-Kuomintang lines. In 1926, Chiang Kai-shek formed the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) and began the Northern Expedition to unite China. Peng's forces joined the NRA, and he became a major. He learned about the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1925.

Becoming a Communist Officer

Between 1926 and 1927, Peng fought in Hunan, helping to capture Changsha and Wuhan. He became a lieutenant-colonel. In 1927, Peng was approached by CCP members. He was interested because their ideas about sharing land matched his own childhood experiences of poverty. He was also disappointed by the fighting within the Kuomintang.

Peng secretly joined the CCP by April 1928. He was stationed in Pingjiang County with orders to fight communist groups. Instead, Peng secretly organized CCP members within his own troops. They took over the county, formed a local council (called a soviet), and joined the Chinese Red Army. After a defeat, Peng retreated to Jinggangshan to join Mao Zedong and Zhu De.

Like many young men, Peng was driven by his experience of poverty. He felt the CCP was the only group truly fighting for what he believed in: national independence and fair land distribution.

Leading the Red Army

Peng and his remaining forces joined the communists at Jinggangshan. He helped save Mao Zedong from being surrounded by KMT forces. Jinggangshan was a good place to hide but not to grow. So, Zhu De and Mao decided to move to Ruijin, Jiangxi, which became the Jiangxi Soviet.

Peng stayed behind to guard Jinggangshan but had to retreat when a large KMT force attacked. He was criticized by Mao for this. Later, Peng returned and led successful raids into southern Hunan, getting more supplies and new soldiers.

In April 1930, Peng became commander of the Red 3rd Army. He attacked Changsha, the capital of Hunan, with 17,000 soldiers. He captured the city on July 30 but was forced to retreat when the KMT counterattacked. Peng tried again in September but suffered heavy losses.

Peng led successful defenses against the KMT during their first three "encirclement campaigns" (attempts to surround and destroy the communists) from 1930 to 1931. His success showed the importance of traditional military operations. In November 1931, Peng was given a political leadership role in the communist movement for the first time. He continued to argue for regular military operations over guerrilla tactics.

The Long March

In October 1933, Chiang Kai-shek launched a massive "fifth encirclement campaign" against the communists. Communist leaders, including Peng, prepared defenses. However, Chiang's forces were too strong, and the communists suffered many defeats. Peng's units shrank from 35,000 to about 20,000 men.

The CCP decided to retreat from Jiangxi. On October 20, 1934, they broke through the KMT lines and began the Long March. It was a very difficult journey. Of the 18,000 men under Peng's command at the start, only about 3,000 remained when they reached their destination in Shaanxi a year later.

During the March, Peng began to agree more with Mao's idea of guerrilla warfare. He supported Mao's rise to power at the Zunyi Conference in January 1935. Peng continued to strengthen the communist base in Shaanxi. In April 1937, Peng became vice commander-in-chief of all Chinese communist forces, second only to Zhu De.

In October 1935, Mao Zedong wrote a famous poem for Peng, praising his bravery as a general. An American journalist, Edgar Snow, visited Peng in 1936 and wrote a lot about him in his book Red Star Over China.

Fighting in World War II

After Japan attacked China in 1937, the KMT and communists agreed to work together to fight the Japanese. Peng was confirmed as a general in this new joint army. Mao Zedong wanted the communists to save their strength for later, but Peng and most other leaders believed they should truly fight the Japanese. Peng's view won out, and the communists cooperated with the KMT.

When Japan invaded Shanxi, the Red Army (renamed the Eighth Route Army) helped the local warlord resist. Peng directed operations from a base in Wutaishan. By 1938, Peng commanded two-thirds of the Eighth Route Army, about 100,000 soldiers.

In July 1940, Peng led the largest communist attack against Japan, called the Hundred Regiments Offensive. About 200,000 regular troops and 200,000 guerrillas took part. They destroyed many bridges, tunnels, and railway tracks used by the Japanese. This disrupted Japanese supply lines until 1942. However, the communists suffered heavy losses.

After this, Peng was called back to Yan'an, the communist base. He was criticized for the campaign, even though Mao had supported it earlier. Peng was not allowed to respond and had to make a "self-criticism." He spent the rest of the war without an active command. From 1942 to 1945, Peng's role was mostly political, and he supported Mao closely.

Leading the People's Liberation Army

Defeating the Kuomintang

Japan surrendered in September 1945, which led to the final stage of the Chinese Civil War. In October, Peng took command of troops in northern China. In March 1946, communist forces were renamed the "People's Liberation Army" (PLA). Peng was put in charge of 175,000 soldiers in the "Northwest Field Army."

Peng's forces were not as well-equipped as others, but they were responsible for defending the communist capital, Yan'an. In March 1947, a large KMT army invaded the area. Peng had to abandon Yan'an but fought long enough for Mao and other leaders to escape safely. Mao wanted Peng to fight a big battle right away, but Peng convinced him to wear down the enemy first.

In May, Peng's forces attacked a supply depot, capturing food, uniforms, and weapons. They eventually defeated the KMT forces in August 1947 in the Battle of Shajiadian, saving Mao and the Central Committee. Peng eventually pushed KMT forces out of Shaanxi by February 1948.

Between 1947 and 1949, Peng's forces took over Gansu, Ningxia, and Qinghai. They also invaded Xinjiang. Most of Xinjiang's defenders surrendered peacefully. After the People's Republic of China was founded on October 1, 1949, Peng was given control over a huge area of Northwest China. His forces completed their takeover of Xinjiang by September 1951.

The Korean War

When North Korea invaded South Korea in June 1950, the United States and United Nations forces entered the war. By October, UN forces crossed into North Korea, getting close to China's border. China's leaders disagreed about whether to join the war. Mao Zedong wanted to intervene, but most others did not.

Mao asked Peng to lead the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) into Korea. Peng flew to Beijing, listened to the debate, and on October 5, decided to support Mao. Peng's support changed the minds of other leaders, and China decided to intervene. Peng was named Commander and Commissar of the PVA until the armistice in 1953. Mao directed the overall strategy, and Zhou Enlai coordinated with the Soviets and North Koreans.

On October 19, 1950, the first wave of Chinese soldiers, over 260,000 men, crossed into Korea. The PVA first fought UN troops on October 25 and pushed them south. Peng directed 380,000 PVA troops to recover the area north of the 38th parallel. Peng then tried to take the area south of the 38th parallel. Chinese soldiers captured Seoul on December 31 but were forced to leave it with heavy losses in March 1951. Peng launched a final campaign in April to retake Seoul, but it failed. The Korean War then became a stalemate near the 38th parallel.

Chinese casualties were very high in the first year of the war. They lacked modern equipment, and supplies were hard to get. UN forces had complete control of the air. Many Chinese soldiers froze to death due to lack of winter clothing. China's lack of artillery and air support meant Peng had to rely on using many soldiers in attacks. Some of the worst losses happened in late 1950 and mid-1951. Over a million Chinese soldiers were killed or wounded during the war. Peng believed the high losses were justified by the goals of communism.

Peng visited Beijing several times to tell Mao and Zhou about the heavy casualties and supply problems. By late 1951, Peng believed the war would last a long time. In February 1952, he angrily spoke about the lack of supplies for soldiers. Zhou Enlai then worked to improve logistics, train pilots, and buy more equipment from the Soviet Union.

Truce talks began in July 1951. Peng was called back to China in April 1952 for a health issue. On July 27, 1953, Peng personally signed the armistice agreement that ended the Korean War. He received a hero's welcome in China.

The Korean War greatly influenced Peng's ideas for the Chinese military. He believed the PLA needed modern training, equipment, and professional standards. He thought military training should be more important than political lessons. He saw the Soviet Army as a good model. Peng believed the CCP's main goal was to improve the lives of ordinary people. This idea later caused problems between him and Mao.

Defense Minister of China

After returning to China in April 1952, Peng took over managing the military. In 1954, he became the most senior military leader in China, second only to Mao. On September 24, 1954, Peng was officially appointed Defense Minister. Soon after, he created a plan to modernize the PLA based on the Soviet military.

Political Activities

Peng had been a member of the Central Committee since 1938 and the Politburo since 1945. But it was only after he moved to Beijing in 1953 that he became active in national politics. He was loyal to Mao at first.

In 1955, Peng supported Mao's efforts to organize farms into large groups (collectivization). He also supported Mao's efforts to arrest people who criticized the CCP later that year.

However, Peng began to dislike Mao's efforts to promote himself as a perfect hero. Peng preferred modesty and simplicity. He opposed hanging portraits of Mao everywhere and singing songs praising him. He once said, "Why put it up? What is put up now will be removed in the future," about a statue of Mao. When soldiers shouted, "Long Live Chairman Mao!" Peng told them, "He will not even live for 100 years! This is a personality cult!"

In 1956, Peng suggested removing a part of the Party Constitution that mentioned "Mao Zedong Thought." Many other senior CCP members agreed, and it was removed from the final version. Peng was reappointed to the Politburo.

Peng also disliked Mao's personal lifestyle, which he thought was too fancy. He continued to call Mao "Old Mao," an equal term used among leaders in earlier times.

Military Activities

Peng led his first military action as Defense Minister in January 1955. He attacked and occupied islands held by the Kuomintang. This led the United States to form a defense agreement with Taiwan, which stopped China from fully defeating the KMT.

Peng traveled to many communist countries after becoming Defense Minister. He visited East Germany, Poland, and the Soviet Union in 1955, meeting with their leaders. He also attended the signing of the Warsaw Pact as an observer.

After his first trip abroad, Peng began to put his "Four Great Systems" into action. This meant creating standardized military ranks, salaries, awards, and rules for joining the army. On September 23, 1955, Peng was named one of the ten marshals of the PLA, China's highest military rank. He introduced military uniforms like those worn by Soviet soldiers. He also changed conscription to voluntary service and set up clear ranks for soldiers. By September 1956, Peng's ideas of professionalism, strict training, and modern equipment were firmly in place in the PLA.

Mao disagreed with these changes. In 1958, Mao convinced Peng to remove some other marshals from high positions, accusing them of copying Soviet methods too much. This cost Peng the support of many military leaders.

Peng was still in command when Mao ordered the shelling of Kinmen and Matsu, islands held by the KMT, in 1958. Peng planned to bombard the islands to make their defenders give up. However, the attack faced problems. The United States helped the KMT supply ships, and KMT fighter jets shot down many Chinese planes. Peng had quietly opposed the operation from the start. He gradually ended the attacks after the PLA faced difficulties. This event hurt Peng's reputation.

Fall from Power

The Great Leap Forward

In 1957, Mao Zedong started a plan called the Great Leap Forward. Farmers were forced to move to large agricultural communes, and private property was taken away. This plan caused a terrible famine across China that lasted for several years, and millions of people died of starvation. By 1959, the economic system in the countryside had broken down.

Peng did not oppose the Great Leap at first. But from 1958, as the problems became clear, he spoke out more. He saw that crops were left to die because young men were forced to work in small, inefficient furnaces to make poor-quality steel. He heard complaints that household items were being melted down for "steel," and houses were torn down for fuel.

On a tour of his home province, Hunan, in late 1958, Peng saw severe food shortages, hungry children, and angry elders. He wrote a poem about what he saw:

- Grain scattered on the ground, potato leaves withered;

- Strong young people have left to make steel;

- Only children and old women reap the crops;

- How can they pass the coming year?

- Allow me to raise my voice for the people!

In March 1959, Peng openly criticized Mao for taking too much personal control of national politics. Mao responded with vague criticisms of Peng. Peng then left on a military tour through Eastern Europe. While he was away, Mao spread negative rumors about Peng among Party leaders.

The Lushan Conference

The Lushan Conference was held in July 1959 to discuss the Great Leap Forward. Mao encouraged Party members to "criticize and offer opinions." Peng had just returned to China and was invited by Mao to attend.

In early meetings, Peng criticized the false reports of agricultural production. He said that "everybody had a share of responsibility, including Comrade Mao Zedong." He also criticized leaders who were afraid to disagree with the Party. Peng then wrote a "letter of opinion" to Mao, explaining his ideas. He gave the letter to Mao on July 14. Mao then shared the letter with all the other leaders at the conference. Peng did not want his letter to be widely read.

In his letter, Peng criticized the poor use of labor and the inefficient backyard furnaces. He spoke about the famine and the shortage of cotton. He said the Chinese people had a right to demand change. Peng blamed the problems on "problems in our way of thinking" and leaders who accepted false reports. He said the Party had forgotten to "seek truth from facts," which had led to their past victories.

Mao saw Peng's letter as a personal attack. On July 23, Mao defended himself, attacking Peng and his supporters. Mao called them "imperialists" and "rightists." He said that if the conference sided with Peng, he would leave the CCP and lead the peasants to "overthrow the government." Other senior leaders, like Zhou Enlai and Liu Shaoqi, did not want to risk splitting the Party. So, they sided with Mao against Peng.

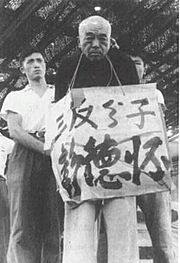

On August 16, the conference passed two resolutions. The first condemned Peng as the leader of an "anti-Party clique" and removed him from his positions as Defense Minister and vice-chairman of the Military Commission. He was allowed to remain in the Politburo but was excluded from meetings for years. The second resolution supported Mao's leadership and subtly called for an end to the Great Leap Forward policies. Peng was forced to make a public "self-criticism," admitting to "severe mistakes." He later said he spoke "against my very heart!" Mao then removed most of Peng's supporters from important jobs.

Later Life and Legacy

In September 1959, Mao replaced Peng as Defense Minister with Lin Biao. This ended Peng's military career. Peng was moved to a suburb of Beijing and lost his marshal's uniform and medals. Lin Biao reversed Peng's military reforms, focusing more on political lessons than professional training.

Peng lived alone under constant watch. He spent his time gardening and studying. He was not completely removed from the Party; he still received documents meant for Politburo members, though he couldn't attend meetings.

From 1960 to 1961, Mao's economic policies continued to cause widespread problems. This made Peng's reputation better among leaders who thought Mao's policies were wrong. In 1961, Peng was allowed to visit Hunan. He found conditions even worse than in 1959. In 1962, Peng wrote a long letter to Mao and the Politburo, defending himself against the accusations from the Lushan Conference and criticizing the Great Leap Forward. He asked to be allowed back into government. However, his efforts were not successful at first.

In September 1965, Mao agreed to give Peng a new job. He was to manage industrial development in Southwest China, focusing on military industries. Peng initially refused, but Mao personally called him and convinced him to accept. Peng worked hard until August 1966, when the Cultural Revolution began.

Persecution During the Cultural Revolution

Peng was one of the first public figures targeted during the Cultural Revolution. Mao's wife, Jiang Qing, personally ordered Red Guards in Sichuan to arrest Peng and bring him to Beijing. On December 25, 1966, Red Guards abducted Peng, put him in chains, and searched his house.

In January 1967, Peng was taken to his first "struggle session." He was paraded in chains before thousands of Red Guards, wearing a tall paper hat and a sign listing his "crimes." He was held in a military prison outside Beijing. His jailers tried to force him to confess to being a "great warlord" and "conspirator." Peng refused. His jailers then treated him very harshly, strapping him down and not allowing him to move. They beat him, breaking several ribs and injuring his back and lungs. These harsh "interrogations" lasted for many hours a day. Peng continued to deny the accusations.

In July 1967, Party leaders decided Peng should be publicly humiliated at a national level. Articles were published across the country, calling Peng a "capitalist" and a "conspirator" who had "always opposed Chairman Mao." The articles accused him of working with foreign countries. This campaign of public criticism against Peng lasted for several months.

In August 1967, Peng was taken to a large "struggle meeting" in a stadium with 40,000 soldiers. He was forced to kneel on a stage for hours while soldiers denounced him. At the end, Lin Biao personally spoke, calling Peng a villain who must be removed.

Peng remained in prison for the rest of his life. In 1970, a military court sentenced him to life imprisonment. This sentence was approved by Lin Biao's chief of staff.

After the death of Lin Biao in 1971, the military tried to improve Peng's living conditions. But years of harsh treatment had severely damaged his health. From late 1972 until his death, Peng was very ill. He died on November 29, 1974. His last wish was to see Zhu De, but it was denied. His body was quickly cremated, and his ashes were sent to Chengdu with a fake name.

Clearing His Name

The CCP leaders kept Peng's death a secret for several years. His wife, who had also been arrested, did not learn of his death until 1978.

Mao Zedong died in 1976. After a power struggle, Peng's old friend, Deng Xiaoping, became China's top leader. One of Deng's first goals was to clear the names of Party members who had been unfairly treated during the Cultural Revolution. Many people, led by General Huang Kecheng, pushed for Peng to be officially honored again.

The Chinese government formally reversed the "wrong" decision about Peng during a meeting from December 18 to 22, 1978. Deng Xiaoping gave a speech announcing Peng's rehabilitation. He praised Peng as "courageous in battle, open and straightforward, honest and strict towards himself." Deng also said that Mao's decision in 1959 to call Peng an "anti-Party clique" leader was "entirely wrong."

From January 1979, the Party encouraged historians and those who knew Peng to write memoirs and articles praising him. In 1980, the Red Guard leader who had directed Peng's arrest was sentenced to nine years in prison for his actions.

After memorial services, Peng's ashes were placed in a special cemetery. In 1999, his nephew and niece moved his ashes to his hometown in Hunan.

In 1986, a book called Memoirs of a Chinese Marshal was put together from documents Peng had written about his life. In 1988, China released stamps to honor the 90th anniversary of Peng's birth. Today, Peng is considered one of China's greatest military leaders of the twentieth century.

See also

In Spanish: Peng Dehuai para niños

In Spanish: Peng Dehuai para niños

- Chinese Red Army and People's Liberation Army – Chinese Civil War

- Eighth Route Army Second Sino-Japanese War

- Outline of the military history of the People's Republic of China

- People's Volunteer Army – Korean War

- List of generals of the People's Republic of China

- Lushan Conference – History of the People's Republic of China (1949–1976)

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |