Ligature (writing) facts for kids

In writing and printing, a ligature happens when two or more letters are joined together to form a single new shape. Think of it like a special blend of letters.

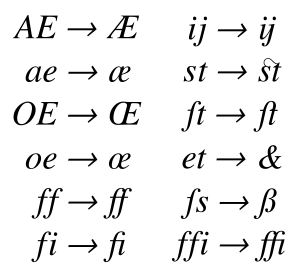

For example, the letters 'a' and 'e' can join to make æ, or 'o' and 'e' can join to make œ. You might see these in some English or French words. Another common one is 'f' and 'i' merging to create fi. This happens because the dot on the 'i' can crash into the top of the 'f' if they are too close. The famous ampersand symbol (&) is also a ligature! It came from combining the Latin letters 'E' and 't', which spelled "et" (meaning "and").

Contents

History of Ligatures

Ligatures have been around for a very long time.

Ancient Times

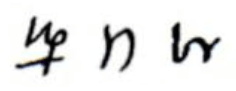

The earliest writing systems, like Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieratic, used many letter combinations that slowly turned into new, separate characters. Other old writing styles, like the Brahmic alphabets and Germanic bind runes, also used ligatures a lot in old books.

These new letter shapes often appeared because people wanted to write faster. Imagine merchants needing to quickly write down notes or deals! Joining letters together and shortening words made record-keeping much quicker than writing everything out in long form.

Medieval and Early Printing

Around the 9th and 10th centuries, monasteries became important places for new ways of writing. Medieval scribes (people who copied books by hand) wrote in Latin. They sped up their writing by combining characters and using notational abbreviations (short forms of words). Some scribes also joined letters just to make the writing look nicer. For example, in a style called blackletter, letters with curved parts that faced each other (like 'b' and 'o') were often overlapped.

When movable type printing was invented around 1450, typefaces (the designs of letters) included many ligatures. This was because they were based on handwriting. Ligatures made printing easier because one metal block could replace common letter pairs. They also allowed for more interesting letter designs that might otherwise bump into each other.

Ligatures in Modern Times

Ligatures started to be used less in the 20th century because they were complex. Simpler fonts, like sans serif styles, often avoided them. Also, new printing machines in the 1970s didn't need special training to use, and they generally didn't include ligatures. Early computer programs also didn't automatically use ligatures, especially since English (which already saw ligatures as optional) was the main language for early computers. This led to many beautiful old typefaces looking "bad" when used digitally.

However, ligatures have become popular again in the 21st century! People are more interested in creating fancy and classic-looking text. Computer programs like Donald Knuth's TeX (used for math and science) brought them back. Many new fonts now include lots of ligatures. This is also because computers now support many different languages and alphabets, some of which use ligatures a lot. New digital printing methods, like OpenType, and features in macOS and Windows now support ligatures.

Today, fonts can have three types of ligatures:

- Standard ligatures: These are needed to make sure letters don't crash into each other.

- Contextual ligatures: These are used in certain situations to make the text look better.

- Historical ligatures: These are used to give text an old-fashioned look.

Latin Alphabet Ligatures

Many ligatures are found in alphabets that use Latin letters.

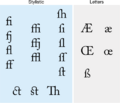

Stylistic Ligatures

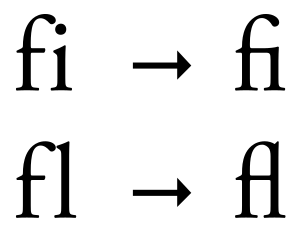

Many ligatures combine the letter f with the letter that comes after it. The most common is fi (f and i). In many fonts, the dot on the 'i' would hit the top curve of the 'f' if they were separate. So, they are combined into one shape where the dot is part of the 'f'. Other 'f' ligatures include fl (f and l), ff (double f), ffi (f, f, i), and ffl (f, f, l).

Sometimes, ligatures are not used if they cross a word part boundary. For example, in German, the word "Schifffahrt" (boat trip) might avoid the 'fff' ligature.

In Turkish, the fi ligature is not used. This is because Turkish has both dotted and dotless 'I' letters, and the ligature would make it hard to tell them apart.

You can still see old ligatures like ſʒ/ſz (which became the German ß) and tʒ/tz on some street signs in Germany. These were once required in a German font style called Fraktur.

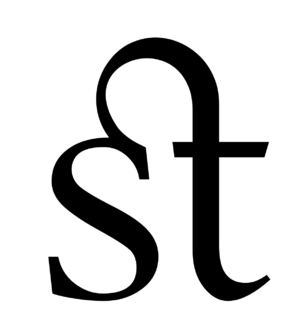

Other ligatures like st (st), ſt (ſt), ch, ck, ct, Qu and Th are also sometimes used in certain fonts.

German ß

The German letter ß (called Eszett or "sharp s") is a special letter in Germany and Austria. It came from a ligature of two 's' letters (ſs) or a long 's' and a 'z' (ſʒ). For a long time, there was no capital version of ß. So, if a word with ß was written in all capital letters, it was changed to "SS" or "SZ". Since 2017, there is an official capital letter for ß (ẞ).

Massachusett ꝏ

In the old writing system for the Massachusett language (a Native American language), the double-o ligature ꝏ was used. It showed a specific 'oo' sound, like in "food." This ligature was even used in the first Bible printed in America! Today, in the Wampanoag language project, this ligature is replaced with the number 8 because it's easier to type and looks similar to another ligature.

Letter W

The letter W is quite new to the Latin alphabet, only appearing around the 7th century. Before that, the 'w' sound was written in different ways. In Old English, a rune called "wynn" (Ƿ) was used. By the 14th century, the letter 'W' developed from two 'V's or 'U's joined together. Because it's so new, only a few European languages use 'W' in their native words.

Æ and Œ

The characters Æ (and its lowercase æ) and Œ (and its lowercase œ) are special. In languages like Danish, Norwegian, or Icelandic, æ is a unique letter with its own place in the alphabet.

However, in modern English, Æ is not a separate letter. It's just another way to spell words like "encyclopædia" (instead of "encyclopaedia" or "encyclopedia"). It came from Medieval Latin words borrowed from Ancient Greek. Similarly, Œ is usually a ligature in French, but it can be replaced by 'oe' if needed.

Umlaut

In German, the letters ä, ö, and ü (which have two dots on top, called an umlaut) actually came from old ligatures. They were originally written as 'ae', 'oe', and 'ue' (or a small 'e' written above the letter). If you can't type the umlauted letters, it's common to write them as 'ae', 'oe', or 'ue'. In Scandinavian languages and Finnish, these umlauted vowels are treated as completely separate letters at the end of the alphabet.

Ring

The ring symbol (like the one over the 'a' in å) also started as a ligature. It was originally an 'a' with another small 'a' on top. The uo ligature (ů) was used in old German but now mostly survives in Czech.

Tilde and Circumflex

The tilde symbol (like the wavy line over the 'n' in Spanish ñ) came from a ligature where an 'n' followed the main letter. For example, "Espanna" became "España." The circumflex (the hat-like symbol in French) came from a silent 's' that was once there.

Byzantine Ȣ

The Byzantine people had a special 'o-u' ligature (Ȣ) that looked like a combination of Greek letters. You can still see this ligature in Greek Orthodox churches today.

International Phonetic Alphabet

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), which shows how sounds are made, used to use ligatures for certain sounds. For example, sounds like ʣ and ʤ are ligatures.

Initial Teaching Alphabet

The Initial Teaching Alphabet, a special alphabet for young children, used many ligatures for long vowel sounds and some consonant sounds.

Rare Ligatures

There are also some very rare ligatures, like ꜳ or ꝏ, which were used in old Nordic languages or the Massachusett language.

Symbols That Started as Ligatures

Some common symbols we use every day actually started out as ligatures!

Ampersand (&)

The most common ligature is the ampersand (&). It was originally a combination of the Latin letters E and t, which spelled "et" (meaning "and"). Even though it looks very different from 'E' and 't' now, it still means "and." Because it's so common, it's usually seen as its own symbol, not just a ligature.

Number Sign (#)

The number sign (#) started as a fancy short way to write the Roman term "libra pondo," which meant "pound weight." Over time, it became the symbol we know today. Now, it's used for numbers (like #1 for "number one") and for weight in pounds. It's also popular on phones and as the hashtag symbol.

At Sign (@)

The at sign (@) might also be a ligature, but its exact origin is a bit of a mystery. One idea is that it came from the French word "à" (meaning "at"), where scribes drew a circle around the 'a'. Another idea is that it came from the Latin word "ad" (meaning "toward"). In the 18th century, it was used in business to show price per unit, like "15 units @ $1." It became super famous with the invention of Email, where it's used to tag specific users.

Dollar Sign ($)

The dollar sign ($) might have started as a ligature for "pesos," but there are other ideas too. It's now a symbol on its own.

Other Symbols

- The Spanish peseta currency sometimes used a ligature ₧ (from Pts).

- The French franc currency often used the ligature ₣ (from Fr).

In astronomy, the symbols for planets also have interesting origins:

- The symbol for Mercury (☿) might be a ligature of Mercury's staff and a cross.

- The symbol for Venus (♀) might be a ligature of two Greek letters.

- The symbol for Jupiter (♃) came from a Greek letter zeta with a line, used as a short form for "Zeus."

- The symbol for Saturn (♄) came from a Greek kappa-rho (κρ), a short form for "Cronus."

- The symbol for the dwarf planet Pluto (♇) is a ligature of 'P' and 'L'.

Other ligatures used as symbols include:

- ⅊ (PL ligature) for a property line in surveying.

- ℄ (CL ligature) for the center line of an object in engineering.

- The interrobang (‽) is a special punctuation mark that combines a question mark and an exclamation mark. It's used when a sentence is both a question and an exclamation, like "Are you really coming over to my house on Friday‽"

Even Alchemy used many symbols that were ligatures, like 🜇 (AR for "aqua regia").

Digraphs

A digraph is when two letters are used together to make a single sound, like "ch" or "sh" in English. These are usually not ligatures because the two letters are still shown separately, even if they are joined in handwriting.

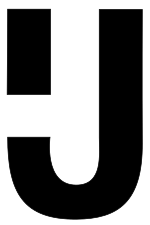

The Dutch "IJ" (ij) is a bit special. It can be seen as a digraph, a ligature, or even its own letter, depending on the rules. In some fonts, the uppercase "IJ" looks like a unique "broken-U" ligature.

Ligatures in Other Alphabets

Ligatures are not just found in Latin writing!

- The Armenian alphabet has ligatures like և (ե+ւ).

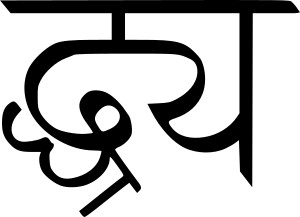

- The Brahmic alphabets (like Devanagari used for Sanskrit and Hindi) use many ligatures for consonant clusters.

- The Georgian script has ligatures like უ (uni), which combines two other letters.

- The Greek alphabet also used ligatures, like a combination of omicron (Ο) and upsilon (Υ).

- Cyrillic ligatures: Letters like Љ and Њ in Serbian and Macedonian Cyrillic were created as ligatures.

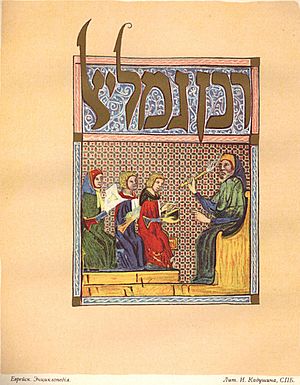

- In the Hebrew alphabet, the letters aleph (א) and lamed (ל) can form a ligature, ﭏ. This is common in old religious texts or texts written in Judeo-Arabic.

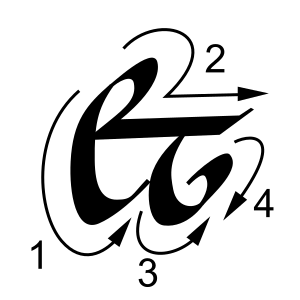

- The Arabic alphabet uses many ligatures because its letters connect differently depending on their position in a word. The "lām + ʼalif" ligature (ﻻ) is a must-have.

- Syriac, another alphabet, also uses many ligatures, especially in the Serto script.

- Urdu, a language from South Asia, uses a beautiful writing style called Nastaʿlīq script. This style needs thousands of ligatures for digital text!

- In American Sign Language, the "I love you" sign is a ligature of the letters I, L, and Y.

- The Japanese language has some old kana ligatures, like ゟ and ヿ, which are used for vertical writing.

- Lao uses three ligatures involving the letter ຫ (h) to help with tones.

- In runic texts, ligatures called "bind-runes" were often used.

Chinese Ligatures

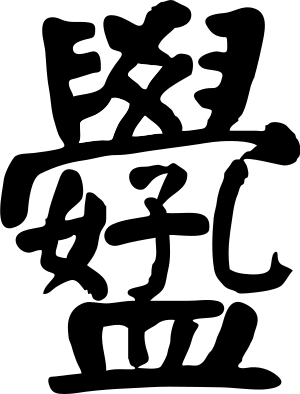

Written Chinese has a long history of combining parts of characters to make new ones. Some of these combinations are called héwén or héshū (Chinese for "combined writing"). They don't represent single words but combine the meaning of several characters.

One popular ligature is used on decorations for Chinese Lunar New Year. It combines four characters (招財進寶) into one symbol, meaning "ushering in wealth and fortune."

In 1924, a Chinese librarian named Du Dingyou created the ligature 圕 from parts of the characters for "library" (圖書館). Even though it has a pronunciation, it's mostly seen as a cool way to write "library."

More recently, a Chinese internet meme called the Grass Mud Horse has its own ligature, combining the three characters for its name (草, 泥, and 马).

Computer Typesetting

Modern computer fonts, especially those using the OpenType format, can automatically use ligatures. This means that when you type "fi," the computer can automatically show the "fi" ligature if the font has it. This type of substitution used to be needed mainly for typesetting Arabic texts, but ligature lookups and substitutions are being put into all kinds of Western Latin OpenType fonts. This feature is very helpful for making text look good, especially for languages like Arabic.

TeX

TeX is a computer program used for typesetting (arranging text on a page), especially for math and science. It automatically uses common ligatures like ff, fi, fl, ffi, and ffl.

CSS

Web designers can control how ligatures are used on websites using CSS3 code. They can choose to turn them on or off, or use specific types of ligatures.

Ligatures in Unicode

Unicode is a system that gives a unique number to every character in every language. Unicode generally says that ligatures are about how text looks, not about defining new characters. So, if a font has an "hr" ligature, it can show it when you type 'h' and 'r'. Unicode usually doesn't add new ligatures unless they are used as distinct letters in a language or as standalone symbols.

Some programs, like Microsoft Word, might turn off ligature use by default. But you can usually turn them on in the settings. Other programs, like LibreOffice Writer, often have standard ligatures turned on automatically.

Here's a table showing some letter pairs and their ligature forms in Unicode:

| Non-ligature | Ligature | Unicode | HTML |

|---|---|---|---|

| AA, aa | Ꜳ, ꜳ | U+A732, U+A733 | Ꜳ ꜳ |

| AE, ae | Æ, æ | U+00C6, U+00E6 | Æ æ |

| AO, ao | Ꜵ, ꜵ | U+A734, U+A735 | Ꜵ ꜵ |

| AU, au | Ꜷ, ꜷ | U+A736, U+A737 | Ꜷ ꜷ |

| AV, av | Ꜹ, ꜹ | U+A738, U+A739 | Ꜹ ꜹ |

| AV, av (with bar) | Ꜻ, ꜻ | U+A73A, U+A73B | Ꜻ ꜻ |

| AY, ay | Ꜽ, ꜽ | U+A73C, U+A73D | Ꜽ ꜽ |

| et | 🙰 | U+1F670 | 🙰 |

| ff | ff | U+FB00 | ff |

| ffi | ffi | U+FB03 | ffi |

| ffl | ffl | U+FB04 | ffl |

| fi | fi | U+FB01 | fi |

| fl | fl | U+FB02 | fl |

| Hv, hv | Ƕ, ƕ | U+01F6, U+0195 | Ƕ ƕ |

| lb | ℔ | U+2114 | ℔ ℔ |

| lL, ll | Ỻ, ỻ | U+1EFA, U+1EFB | Ỻ ỻ |

| OE, oe | Œ, œ | U+0152, U+0153 | Œ œ |

| OO, oo | Ꝏ, ꝏ | U+A74E, U+A74F | Ꝏ ꝏ |

| ɔe | ꭢ | U+AB62 | ꭢ |

| ſs, ſz | ẞ, ß | U+1E9E, U+00DF | ß |

| st | st | U+FB06 | st |

| ſt | ſt | U+FB05 | ſt |

| TZ, tz | Ꜩ, ꜩ | U+A728, U+A729 | Ꜩ ꜩ |

| ue | ᵫ | U+1D6B | ᵫ |

| uo | ꭣ | U+AB63 | ꭣ |

| VV, vv | W, w | U+0057, U+0077 | W w |

| VY, vy | Ꝡ, ꝡ | U+A760, U+A761 | Ꝡ ꝡ |

| ſs | Ꟗ ꟗ | U+A7D6, U+A7D7 | ꟗ ꟗ |

Contemporary Art

Ligatures are even used in modern art! For example, the Chinese artist Xu Bing creates art where he combines Latin letters to make them look like Chinese characters. It's a cool way to blend different writing styles.

Images for kids

In Spanish: Ligadura (tipografía) para niños

In Spanish: Ligadura (tipografía) para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |