Marcel Janco facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marcel Janco

|

|

|---|---|

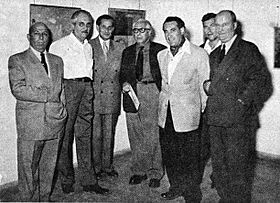

Janco in 1954

|

|

| Born |

Marcel Hermann Iancu

24 May 1895 |

| Died | 21 April 1984 (aged 88) Ein Hod, Israel

|

| Nationality | Romanian, Israeli |

| Education | Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich |

| Known for | Oil painting, collage, relief, illustration, found object art, linocut, woodcut, watercolor, pastel, costume design, interior design, scenic design, ceramic art, fresco, tapestry |

| Movement | Postimpressionism, Symbolism, Art Nouveau, Cubism, Expressionism, Futurism, Primitivism, Dada, Abstract art, Constructivism, Surrealism, Art Deco, Das Neue Leben, Contimporanul, Criterion, Ofakim Hadashim |

| Awards |

|

Marcel Janco (born Marcel Hermann Iancu; 24 May 1895 – 21 April 1984) was a famous Romanian and Israeli visual artist, architect, and art thinker.

Janco was one of the most important Jewish thinkers in Romania during his time. He faced unfair treatment because he was Jewish before and during World War II. In 1941, he moved to what was then called British Palestine. He won important awards like the Dizengoff Prize and the Israel Prize. He also helped start Ein Hod, a special village for artists.

Biography

Early Life and Art Beginnings

Marcel Janco was born on May 24, 1895, in Bucharest, Romania. His family was well-off. His father, Hermann Zui Iancu, was a textile merchant. Marcel studied drawing with a Romanian Jewish painter named Iosif Iser.

As a teenager, Marcel traveled a lot with his family to places like Austria-Hungary, Switzerland, Italy, and the Netherlands. At high school, he met other students who would become his friends and fellow artists. One of them was Tzara, who later became famous. Janco also became friends with the pianist Clara Haskil, and his first published drawing was of her in 1912.

In October 1912, Marcel and his brother Jules joined Tzara to edit a magazine called Simbolul. Janco was the main graphic designer for the magazine, which featured modern poets.

Swiss Adventures and Dada Art

Marcel Janco decided to leave Romania and moved to Zurich, Switzerland, with his brothers. This was around the start of World War I. Marcel studied architecture at the Federal Institute of Technology, but he really wanted to focus on painting.

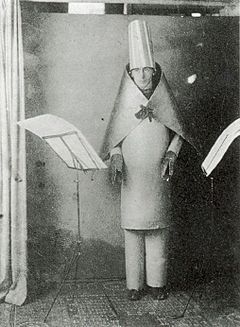

In Zurich, the Janco brothers met Hugo Ball and other artists at a place called Cabaret Voltaire. This place became famous for its wild and new art performances. Marcel Janco was a big part of these events. He made strange, funny masks for the performers to wear. These masks were very important and helped create a new style of theater for the artists, who soon called themselves the Dadaists. Janco also drew pictures for Dada advertisements.

Moving Towards New Art Styles

By 1917, Marcel Janco started to move away from the Dada movement. He still made art for Dada books, but he wanted to try different styles. He became interested in a style called Constructivism, which focused on simple shapes and clear designs. He joined a group called Das Neue Leben ("The New Life"), which believed in teaching modern art and connecting it with socialist ideas.

Return to Romania and Architecture

In December 1919, Marcel and Jules left Switzerland for France. Marcel got married in France. Later, in 1921, Janco and his wife moved back to Romania. He became an architect, even though he wasn't officially licensed yet. He started designing buildings, including houses for his own family. His early designs were simple and modern.

He quickly reconnected with the art scene in Romania. His friends described him as very charming and smart. He also taught art in his studio in Bucharest.

Starting Contimporanul Magazine

In 1922, Janco and his friend Vinea started an important art magazine called Contimporanul. This magazine became the longest-running modern art publication in Romania. At first, it was about politics, but by 1923, it focused more on art and culture. Janco helped choose the art and international news for the magazine.

In 1924, Janco helped organize the Contimporanul International Art Exhibit. This show brought together major modern art styles from across Europe.

Modern Buildings in Bucharest

In the late 1920s, Janco opened his own architecture studio with his brother Jules. They called it Birou de Studii Moderne (Office of Modern Studies). Janco believed Bucharest needed a modern makeover, as it was a bit messy and old-fashioned.

He started getting jobs to design buildings from 1926 onwards. He helped make a style called functionalism popular in Romania. This style focused on making buildings useful and simple, without much decoration.

One of his most important designs was the Villa for Jean Fuchs, built in 1927. This building was very new for Bucharest. It had complex shapes, different kinds of windows, and a flat roof. People in the neighborhood were surprised by it, but Janco continued to design similar modern villas.

By 1938, Janco and his brother had designed about 40 buildings in Bucharest. Many of these were in the richer northern parts of the city, but also in the Jewish Quarter, showing his family and community connections.

He designed many modern villas for wealthy clients. He also designed his first apartment building in 1931, which had bold, projecting shapes. He even designed a private hospital in Predeal, outside Bucharest, which had long, horizontal lines and a zigzag effect.

Marcel Janco had a daughter, Josine, from his first marriage. He later divorced and remarried Clara "Medi" Goldschlager, and they had another daughter, Deborah. His family lived a comfortable life, traveling and spending summers by the sea.

Art and Politics in the 1930s

Janco continued to be the art editor for Contimporanul until it closed in 1929. He also wrote for other art and architecture magazines. In 1932, his villa designs were included in a guide to modern architecture.

In the early 1930s, Janco joined a group called Criterion. This group was for young Romanian thinkers who wanted to redefine their national identity using modern ideas.

In 1934, Janco wrote an essay called "Urbanism, Not Romanticism," where he pushed for modern city planning in Bucharest. He believed Bucharest could become a "garden city" without making the same mistakes as Western cities.

The mid-1930s were his busiest time as an architect. He designed more villas, small apartment buildings, and even larger ones. His Bazaltin Company headquarters, a nine-story building with offices and apartments, was built in 1935 and is still well-known today.

Facing Hard Times and Moving to Israel

By the late 1930s, Janco and his family faced a rise in antisemitism (hatred towards Jewish people) and the growth of fascist groups. Janco became interested in Zionism, the idea of a Jewish homeland in Israel. He visited British Palestine and started planning to move his family there.

In 1939, the government in Romania started enforcing laws that discriminated against Jewish people. Many of the buildings Janco designed, which had Jewish owners, were taken by the authorities. Janco was also stopped from publishing his work in Romania.

During the first two years of World War II, Janco was still in Romania. He helped Jewish refugees who were fleeing from Nazi-occupied Europe. He heard terrible stories about concentration camps. He finally decided to leave in January 1941, after witnessing a violent event against Jewish people in Bucharest.

Janco, his wife, and their two daughters left Romania in February 1941. They traveled through Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Transjordan, finally arriving in Tel Aviv, Palestine. Janco found work as an architect for the city government. He learned more about the terrible events of the Holocaust.

Life in Israel

In British Palestine, Marcel Janco became a key figure in the development of local Jewish art. He was recognized as a leading artist, winning the Dizengoff Prize in 1945 and 1946.

After Israel became an independent country in 1948, Janco helped with planning and designing national parks. He helped turn the Old Jaffa area into a community for artists. He won the Dizengoff Prize again in 1950 and 1951. His art was shown in New York City in 1950, and he represented Israel at the Venice Biennale in 1952.

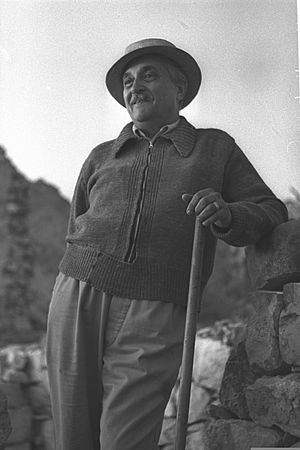

In 1953, Marcel Janco started his most important project in Israel. He found a deserted village called Ein Hod. He felt it shouldn't be destroyed, so he got permission to rebuild it with other Israeli artists. Janco became the first mayor of Ein Hod, turning it into a special art colony and tourist spot.

In the 1950s, Janco also helped start the Ofakim Hadashim ("New Horizons") group, which was for Israeli painters who liked abstract art. He continued to try new art forms, like reliefs and tapestries. He also drew humorous illustrations for Don Quixote.

He received more awards, including the Histadrut union's prize in 1958 and the Israel Prize in 1967 for his painting.

In 1960, some Palestinians tried to reclaim the land in Ein Hod. Janco helped organize a defense force for the community. He also tried to keep in touch with Romania, sending art albums to his friends there.

One of the last public events Janco attended was the opening of the Janco-Dada Museum at his home in Ein Hod. He passed away in 1984.

Work

From Early Influences to Dada Art

Janco's earliest artworks show the influence of his teacher, Iosif Iser, and a style called Postimpressionism. He also discovered the work of French artists like André Derain. His drawings for Simbolul magazine had an Art Nouveau and Symbolist look.

Later, he was influenced by Futurism, which focused on speed and modern life. He also adopted Expressionism, an art style that shows strong feelings and emotions. His self-portraits and paintings of clowns are good examples of Romanian Expressionism.

During his time at Cabaret Voltaire, Janco's paintings mixed Cubism (using geometric shapes) and Futurism with Dada ideas. His art was described as "zigzag naturalism" because it was a bit distorted but still recognizable. He was also one of the first Dada artists to use "found object art," where everyday objects are turned into art. His collages and reliefs were very original and brave experiments in abstract art.

Simple and Collective Art

As a Dada artist, Janco was interested in raw, "primitive" art, which he believed came from natural instincts. He felt that African art, ancient art, and medieval art were more real and "spiritual" than later art styles. He also believed art should be connected to everyday life and crafts.

Janco's art also showed connections to Hasidic Judaism and the darker colors often used in 20th-century Jewish art.

Beyond Constructivism

For a while, Janco focused on abstract and semi-abstract art, seeing basic geometric shapes as pure forms. After 1930, he returned to a style similar to early Cubism, as seen in his painting Peasant Woman and Eggs. He also painted cityscapes, seascapes, and still life pictures.

In architecture, Janco saw himself and other "Radical Artists" as leaders of modern city planning. He believed in "collectivism" in art, meaning art should be part of life. His architectural work was all about functionalism, making buildings useful and simple, like crystals. His buildings often had Art Deco elements, like "ocean liner"-style balconies. He also designed furniture that was simple, comfortable, and not overly fancy.

Janco's goal for Bucharest was to turn it into a "garden city," a planned community with green spaces. He believed the city had a chance to avoid the mistakes of Western cities.

Holocaust Art and Israeli Abstract Art

After his first visit to Palestine, Janco started painting optimistic landscapes. But during World War II, he returned to Expressionism, focusing on big, important themes. His 1945 painting Fascist Genocide showed the horrors of the war. His sketches of the Bucharest Pogrom were very powerful and different from his earlier art. He said he drew them "with the thirst of one who is being chased around."

After the war, he changed his art to focus on his new country, Israel. He started painting in pure abstraction, which he saw as the "language" of a new age. He also connected his art to Jewish traditions and symbols. He continued to paint colorful, semi-figurative landscapes.

His Ein Hod project was a big part of his interest in folk art. He saw it as his "last Dada activity." He tried to preserve the existing Arab-style buildings in the village, rather than building completely new ones.

Legacy

Marcel Janco is remembered for many things. In Western art history, he's known as one of the founders of Dada in Zurich in 1916. In Romania, he's known as a key figure in the modern art movement between the world wars and for designing many of Romania's first modern buildings. In Israel, he's famous as the "father" of the Ein Hod artists' colony and for his teaching.

His memory is kept alive mainly by the Janco-Dada Museum in Ein Hod. The museum was damaged by a forest fire in 2010 but reopened and now has a permanent exhibit of his art. His paintings still influence artists in Israel today.

In Romania, after the communist government took power, Janco's contributions were often ignored. Many of the villas he designed were taken by the state. However, most of his buildings in Bucharest survived and are now considered valuable. Experts are concerned that some are being changed too much with modern additions.

Janco is still seen as an important model for Romanian architects and city planners. His ideas about urban planning were collected in a book. His Bazaltin building is now used as offices for a TV station.

His art has been shown in many exhibitions around the world, including in Berlin, Essen, and Budapest. Some shows have focused specifically on his rediscovered Holocaust paintings and drawings. His artworks are also sold at high prices in art auctions.

See also

In Spanish: Marcel Janco para niños

In Spanish: Marcel Janco para niños

- Visual arts in Israel

- Portrait of a Girl

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |