Mary Celeste facts for kids

An 1861 painting of Mary Celeste (named Amazon at the time) by an unknown artist

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | Amazon |

| Port of registry | Parrsboro, Nova Scotia |

| Builder | Joshua Dewis, Spencer's Island, Nova Scotia |

| Launched | May 18, 1861 |

| Fate | Ran aground Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, 1867, salvaged and given to American owners |

| Name |

|

| Port of registry | Principally New York or Boston |

| Builder | Rebuilt 1872, New York (yard not named) |

| Fate | Deliberately wrecked off the coast of Haiti, 1885 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage |

|

| Length | 99.3 ft (30.3 m) as built, 103 ft (31 m) after rebuild |

| Beam | 22.5 ft (6.9 m) as built, 25.7 ft (7.8 m) after rebuild |

| Depth | 11.7 ft (3.6 m) as built, 16.2 ft (4.9 m) after rebuild |

| Decks | 1, as built, 2 after rebuild |

| Sail plan | Brigantine |

The Mary Celeste (often mistakenly called Marie Celeste) was an American merchant ship. It was a brigantine, a type of sailing ship with two masts. On December 4, 1872, the ship was found empty and drifting in the Atlantic Ocean. This was near the Azores Islands.

Another ship, the Canadian brigantine Dei Gratia, found her. The Mary Celeste was messy but still able to sail. Some of her sails were up, but her lifeboat was gone. The last entry in her logbook was from ten days earlier. She had left New York City on November 7, heading for Genoa, Italy. When found, she still had plenty of food and supplies. Her cargo of alcohol was untouched. The captain's and crew's personal items were still there. No one who had been on board was ever seen again.

The Mary Celeste was built in Spencer's Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. She was launched in 1861 and first named Amazon. In 1868, American owners bought her and changed her name to Mary Celeste. She sailed without problems until her 1872 voyage. After she was found, hearings were held in Gibraltar. Officials looked into many ideas. These included a mutiny by the crew or pirates attacking the ship. They also considered if it was a plan to get insurance money. But there was no strong proof for any of these ideas. Because of this, the people who found her got less money than expected.

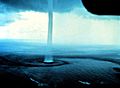

Since the hearings didn't solve the mystery, people kept guessing what happened. Many false details and made-up stories have been added over time. Some ideas include alcohol fumes affecting the crew. Others suggest underwater earthquakes, waterspouts, or even a giant squid attack. Some people even think it was something paranormal.

After the Gibraltar hearings, the Mary Celeste kept sailing with new owners. In 1885, her captain purposely wrecked her off Haiti. He did this to try and get insurance money. The story of her being found empty in 1872 has been told many times. It has appeared in books, plays, and movies. The ship's name has become a common phrase for something mysteriously deserted. In 1884, Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a short story about the mystery. He called the ship Marie Celeste, which made that spelling more common.

Contents

Building the Ship: Early Years

The Mary Celeste began as the Amazon in late 1860. She was built in Spencer's Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. Local wood was used to build the ship. She had two masts and was a brigantine. The ship was launched on May 18, 1861. She was registered in nearby Parrsboro on June 10, 1861. Her papers said she was about 99.3 feet (30.3 m) long and 25.5 feet (7.8 m) wide. She weighed 198.42 gross tons. Nine local people owned her, led by Joshua Dewis, her builder. Robert McLellan, the first captain, was also an owner.

For her first trip in June 1861, the Amazon went to Five Islands, Nova Scotia. She picked up wood to take to London. Captain McLellan got sick while loading the ship. He died on June 19. John Nutting Parker became the new captain. The Amazon then continued her trip to London. She had more problems on this voyage. She hit fishing gear near Eastport, Maine. After leaving London, she crashed into and sank another ship in the English Channel.

Captain Parker commanded the ship for two years. During this time, the Amazon mainly traded in the West Indies. In November 1861, she sailed to France. A famous artist might have painted her in Marseille. In 1863, William Thompson became captain. He stayed in command until 1867. These were calm years for the ship. An officer later said, "Not a thing unusual happened." In October 1867, a storm hit the Amazon near Cape Breton Island. She was so badly damaged that her owners gave up on her. Alexander McBean bought the damaged ship on October 15.

New Owners and a New Name

Within a month, McBean sold the damaged ship. In November 1868, an American sailor from New York, Richard W. Haines, bought her. Haines paid US$1,750 for the wreck. He then spent $8,825 to fix her up. He became her captain. In December 1868, he registered her in New York as an American ship. He gave her a new name: Mary Celeste.

In October 1869, Haines's creditors took the ship. She was sold to a group of New York businessmen. James H. Winchester led this group. Over the next three years, the owners changed a few times. But Winchester always owned at least half of the ship. We don't have records of what the Mary Celeste did during this time. In early 1872, the ship had a big repair job. It cost $10,000 and made her much bigger. Her length grew to 103 feet (31 m), and her width to 25.7 feet (7.8 m). Her depth became 16.2 feet (4.9 m). Workers added a second deck. They also made other changes, like extending the poop deck. The ship's size increased to 282.28 tons. By October 29, 1872, Winchester owned six shares of the ship. Two other small investors owned one share each. The remaining four shares were owned by the ship's new captain, Benjamin Spooner Briggs.

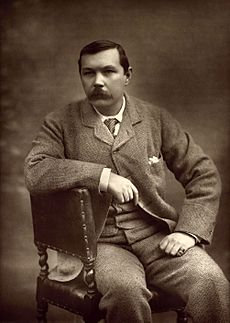

Captain Briggs and His Crew

Benjamin Briggs was born in Wareham, Massachusetts, in 1835. He was one of five sons of a sea captain. Most of his brothers also became sailors, and two became captains. Benjamin was a very religious person. He read the Bible often and shared his faith. In 1862, he married his cousin, Sarah Elizabeth Cobb. They spent their honeymoon on his ship, the Forest King, sailing in the Mediterranean. They had two children: Arthur, born in 1865, and Sophia Matilda, born in 1870.

By the time Sophia was born, Briggs was a respected captain. He thought about stopping his sea career. He wanted to start a business with his brother Oliver, who also wanted to stop sailing. They didn't do that, but each invested in a ship. Oliver bought a share in the Julia A. Hallock. Benjamin invested in the Mary Celeste. In October 1872, Benjamin took command of the Mary Celeste. This was her first trip after the big repairs in New York. She was going to Genoa, Italy. He decided to bring his wife and baby daughter with him. His older son stayed home with his grandmother.

Briggs carefully chose his crew for this trip. The first mate, Albert G. Richardson, was married to Winchester's niece. He had sailed with Briggs before. The second mate, Andrew Gilling, was about 25 and from New York. The steward, Edward William Head, was newly married. Winchester personally recommended him. The four regular sailors were German brothers, Volkert and Boz Lorenzen, Arian Martens, and Gottlieb Goudschaal. They were described as "peaceable and first-class sailors." Before the trip, Briggs wrote to his mother. He said he was very happy with the ship and crew. Sarah Briggs told her mother that the crew seemed "quietly capable."

The Ship is Found Empty

Leaving New York

On October 20, 1872, Captain Briggs came to Pier 50 in New York City. He was there to watch the loading of the ship's cargo. It was 1,701 barrels of alcohol. His wife and baby daughter joined him a week later. On Sunday, November 3, Briggs wrote to his mother. He said he planned to leave on Tuesday. He added that "our vessel is in beautiful trim."

On Tuesday morning, November 5, the Mary Celeste left Pier 50. Captain Briggs, his wife, daughter, and seven crew members were on board. They moved into New York Harbor. The weather was not good, so Briggs decided to wait. He anchored the ship near Staten Island. Sarah used this delay to send a last letter to her mother-in-law. She wrote, "Tell Arthur, I make great dependence on the letters I shall get from him." Two days later, the weather improved. The Mary Celeste left the harbor and sailed into the Atlantic Ocean.

While the Mary Celeste was getting ready, the Canadian ship Dei Gratia was nearby. She was in Hoboken, New Jersey. She was waiting for a cargo of oil to take to Genoa. Captain David Morehouse and first mate Oliver Deveau were from Nova Scotia. Both were very skilled sailors. Captains Briggs and Morehouse had similar interests. Some writers think they knew each other. Some stories say they were close friends and ate dinner together before the Mary Celeste left. But this is mostly based on a memory from Morehouse's widow, 50 years later. The Dei Gratia left for Gibraltar on November 15. She followed the same general route, eight days after the Mary Celeste.

The Empty Ship is Found

On December 4, 1872, the Dei Gratia was in the North Atlantic. This was between the Azores and Portugal. Around 1 p.m., Captain Morehouse came on deck. The helmsman saw a ship sailing strangely about 6 miles (9.7 km) away. The ship's odd movements and sails made Morehouse think something was wrong. As the ship came closer, he saw no one on deck. His signals got no reply. So, he sent Mate Deveau and Second Mate John Wright in a small boat to check.

They saw the name Mary Celeste on the back of the ship. They climbed aboard and found it empty. The sails were partly set and damaged. Some were missing, and ropes hung loosely. The main hatch cover was closed. But the front and back hatches were open, with their covers nearby. The ship's only lifeboat, a small yawl, was gone. It had been stored near the main hatch. The binnacle, which holds the compass, was moved. Its glass cover was broken. There was about 3.5 feet (1.1 m) of water in the bottom of the ship. This was a lot, but not dangerous for a ship of this size. A makeshift stick for measuring water in the hold was found on deck.

They found the ship's logbook in the mate's cabin. The last entry was from 8 a.m. on November 25. This was nine days earlier. It said the Mary Celeste was then near Santa Maria Island in the Azores. This was almost 400 nautical miles (740 km) from where the Dei Gratia found her. Deveau saw that the cabins were wet and messy from water. But they were otherwise in good order. He found personal items in Briggs's cabin, like a sword. But most of the ship's papers and the captain's navigation tools were gone. The kitchen equipment was neatly put away. No food was being cooked, but there was plenty in storage. There were no clear signs of fire or fighting. It looked like everyone had left the ship in an orderly way using the missing lifeboat.

Deveau went back to tell Morehouse what he found. Morehouse decided to take the empty ship to Gibraltar, 600 nautical miles (1,100 km) away. Under sea law, someone who saves a ship and its cargo gets a share of its value. Morehouse split his crew of eight. He sent Deveau and two sailors to the Mary Celeste. He and four others stayed on the Dei Gratia. The weather was mostly calm on the way to Gibraltar. But each ship had too few crew members, so they moved slowly. The Dei Gratia reached Gibraltar on December 12. The Mary Celeste arrived the next morning after hitting fog. She was immediately held by the court for salvage hearings. Deveau wrote to his wife that bringing the ship in was hard. But he said he would be "well paid for the Mary Celeste."

Gibraltar Hearings

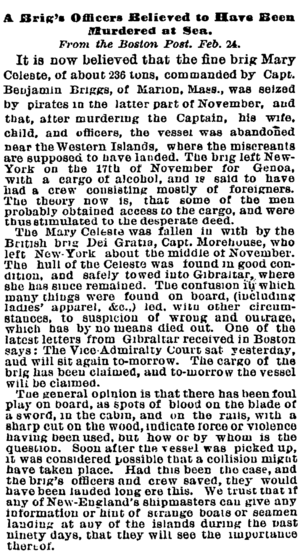

The court hearings began in Gibraltar on December 17, 1872. Sir James Cochrane, the chief judge, led them. Frederick Solly-Flood, the Attorney General of Gibraltar, handled the case. Flood was known for being very sure of his opinions. He quickly believed that a crime had happened. The New York Shipping and Commercial List newspaper agreed on December 21. It said, "The inference is that there has been foul play somewhere."

On December 23, Flood ordered an inspection of the Mary Celeste. John Austin, a shipping expert, did this with a diver. Austin saw cuts on the ship's front. He thought a sharp tool made them. He also found possible blood traces on the captain's sword. His report said the ship didn't seem to have been in bad weather. He noted a sewing machine oil bottle standing upright. Austin didn't consider if the bottle might have been put back later. The court also didn't ask about this. The diver's report said the ship had not crashed or run aground. Other naval captains also inspected the ship. They agreed with Austin about the cuts. They also found stains on a ship's rail that might have been blood. There was also a deep mark, possibly from an axe. These findings made Flood more suspicious. He thought human actions, not nature, caused the mystery. On January 22, 1873, he sent his reports to London. He added his own idea. He thought the crew got into the alcohol. Then they killed the Briggs family and officers. He believed they cut the ship's front to fake a crash. Then they fled in the lifeboat. Flood also thought Morehouse and his crew were hiding something. He believed the Mary Celeste was abandoned further east. He also thought the logbook was changed. He couldn't believe the Mary Celeste could have traveled so far without a crew.

James Winchester, one of the owners, arrived in Gibraltar on January 15. He wanted to know when the Mary Celeste could deliver her cargo. Flood demanded a $15,000 payment, which Winchester didn't have. Winchester realized Flood thought he might have planned for the crew to kill Briggs. On January 29, Winchester argued with Flood. He spoke highly of Captain Briggs. He said Briggs would only leave the ship in extreme danger.

Flood's ideas of mutiny and murder faced problems. Scientific tests showed the stains on the sword were not blood. Then, Captain Shufeldt of the US Navy gave a report. He said the marks on the ship's front were natural, not man-made.

With no strong proof, Flood had to release the Mary Celeste on February 25. Two weeks later, she left Gibraltar for Genoa. A new crew, led by Captain George Blatchford, was on board. The payment for saving the ship was decided on April 8. The court awarded £1,700. This was about one-fifth of the ship and cargo's total value. This was much lower than expected. Some thought it should have been two or three times more. Judge Cochrane criticized Morehouse for sending his own ship to deliver its cargo earlier. Cochrane's words suggested wrongdoing. This made Morehouse and his crew seem suspicious to the public.

Possible Explanations

Why Did They Leave?

Most people agree that something very unusual must have happened. It caused everyone to leave a good ship with plenty of supplies. The Gibraltar hearings found no proof of murder or a plan. But suspicions of foul play remained. Flood and some newspapers briefly thought Winchester might have planned to get insurance money. But Winchester proved these claims wrong.

One idea is that Captain Briggs and Captain Morehouse planned to share the salvage money. Some say they were friends, which makes this seem possible. But if they planned this, they wouldn't have created such a big mystery. Also, why would Briggs leave his son Arthur behind if he planned to disappear forever?

Another idea is that pirates attacked the ship. Pirates were active off Morocco in the 1870s. However, pirates usually steal things. But the personal items of the captain and crew were left untouched. Some of these items were valuable.

The Missing Lifeboat

Captain Briggs's cousin, Oliver Cobb, had an idea. He thought the crew might have gotten into the small lifeboat temporarily. He thought a rope might have tied the lifeboat to the ship. This would let them return once danger passed. But if the rope broke, the Mary Celeste would sail away empty. The lifeboat and its occupants would be left adrift. It doesn't make sense to tie a lifeboat to a ship you think is about to explode or sink. Briggs was an experienced captain. Would he have left the ship in a panic? If the Mary Celeste was about to explode, it would still be safer than a small lifeboat in the open sea.

Arthur N. Putman, an insurance expert, also had a lifeboat theory. He noted that only one lifeboat was missing. He found that its rope was cut, not untied. This suggests a quick departure. The ship's log mentioned rumbling and small explosions from the cargo hold. Alcohol cargo can release explosive gas, and these sounds are common. Putman thought there was a bigger explosion one day. Perhaps a sailor went below deck with a light or lit cigar. This could have set off the fumes, causing an explosion. It might have been strong enough to blow off the hatch cover, which was found in an unusual spot. Putman believed that in a panic, the captain, his family, and the crew quickly got into the lifeboat. They cut the rope and left the ship.

Natural Events

Many people think some alarming event must have happened. It would have made everyone leave a good ship with plenty of food. Mate Deveau had an idea based on the sounding rod found on deck. He thought Briggs might have left the ship after a false reading. Maybe the pumps broke, making it seem like the ship was taking on water quickly.

A strong waterspout hitting the ship could explain the water inside and the damaged sails. A waterspout creates low air pressure. This could have pushed water from the bottom of the ship into the pumps. This would make the crew think the ship had taken on more water than it had. They might have thought it was sinking.

Other ideas include seeing an iceberg or fearing running aground. An iceberg drifting so far south was unlikely. Other ships would have seen it. Another theory is that the Mary Celeste drifted towards a reef near Santa Maria Island. This happened when the ship was still. Briggs might have feared hitting the reef. He could have launched the lifeboat to reach land. Then, the wind might have picked up, blowing the Mary Celeste away from the reef. The rising seas could have swamped the lifeboat. But if the ship was still, all sails would have been set. Yet, many sails were found furled (rolled up).

An earthquake on the seabed could have shaken the ship. This might have damaged some of the alcohol cargo. This would release harmful fumes. Fear of an explosion could have made Briggs order everyone to leave. The open hatches suggest someone inspected or tried to air out the hold. In 1886, the New York World newspaper mentioned a ship carrying alcohol that exploded. In 1913, the same paper suggested that alcohol leaking from barrels caused gases. These gases might have caused or threatened an explosion in the Mary Celeste's hold. Oliver Cobb, Briggs's cousin, strongly supported this idea. He thought rumbling sounds, fumes, and maybe an explosion would be scary enough. Briggs might have left the ship quickly before it exploded. In his hurry, he might not have tied the lifeboat properly. A sudden breeze could have blown the ship away from the lifeboat. The people in the lifeboat would then be lost at sea. However, there was no explosion damage. The cargo was mostly fine when found. This makes this theory less likely.

In 2006, a TV show did an experiment. A chemist built a model of the ship's hold. He used paper boxes for the barrels. He used gas to create an explosion. There was a big blast and a ball of flame. But there was no fire damage inside the model. This experiment helped bring back the "explosion" theory.

Myths and False Stories

Over the years, facts and made-up stories about the Mary Celeste got mixed up. In June 1883, the Los Angeles Times retold the story with invented details. It said, "Every sail was set, the tiller was lashed fast, not a rope was out of place. The fire was burning in the galley. The dinner was standing untasted and scarcely cold."

The most famous retelling was a story in Cornhill Magazine in January 1884. This story made sure the Mary Celeste mystery would never be forgotten. It was an early work by Arthur Conan Doyle, who was a ship's doctor at the time. Conan Doyle's story, "J. Habakuk Jephson's Statement", did not stick to the real facts. He renamed the ship Marie Celeste. The captain's name was J. W. Tibbs. The voyage happened in 1873, from Boston to Lisbon. The ship had passengers. In the story, a man named Septimius Goring hates white people. He convinces some crew members to kill Tibbs. They take the ship to Africa. Everyone else on board is killed. Only Jephson is saved because he has a special charm. Conan Doyle didn't expect his story to be taken seriously. But the U.S. consul in Gibraltar, who was still there, was curious. He asked if any part of the story was true.

In 1913, The Strand Magazine published a story. It claimed to be from a survivor named Abel Fosdyk, the Mary Celeste's steward. But no such person was on the crew list. In this version, the crew gathered on a swimming platform to watch a contest. The platform collapsed, and everyone but Fosdyk drowned or was eaten by sharks. Unlike Conan Doyle's story, the magazine presented this as a serious solution. But it had many simple mistakes. For example, it called the captain "Griggs" instead of Briggs. It also said Briggs's daughter was seven, not two. It claimed there were 13 crew members.

In 1924, the Daily Express published a story by Captain R. Lucy. He said his information came from the Mary Celeste's former bosun. But again, no such person was on the crew list. In this story, Briggs and his crew are the bad guys. They find an empty steamer. They board it and find £3,500 of gold and silver. They decide to split the money, leave the Mary Celeste, and start new lives in Spain. They use the steamer's lifeboats to get there. It's surprising that such an unlikely story was believed for a while.

Chambers's Journal in 1904 suggested that a giant octopus or squid took everyone from the Mary Celeste one by one. Giant squid can be 15 meters (49 ft) long. They have been known to attack ships. But such a creature couldn't have taken the lifeboat or the captain's navigation tools. Other ideas suggest paranormal events. One old astrology journal called the Mary Celeste story a "mystical experience." It linked it to the Great Pyramid of Gizeh and the lost continent of Atlantis. The Bermuda Triangle has also been mentioned. But the Mary Celeste was found in a completely different part of the Atlantic. Some fantasies even suggest aliens took the crew.

Later Life and Final Voyage

The Mary Celeste left Genoa on June 26, 1873. She arrived in New York on September 19. The Gibraltar hearings and newspaper stories of bloodshed made her an unpopular ship. She "rotted on wharves where nobody wanted her." In February 1874, the owners sold the ship at a big loss. A group of New York businessmen bought her.

Under her new owners, the Mary Celeste mainly sailed to the West Indies and Indian Ocean. She often lost money. News of her travels sometimes appeared. In February 1879, she was at St. Helena island. Her captain, Edgar Tuthill, had fallen ill and needed medical help. Tuthill died on the island. This made people think the ship was cursed. He was the third captain to die early. In February 1880, the owners sold the Mary Celeste to a group in Boston. Wesley Gove led this group. A new captain, Thomas L. Fleming, stayed until August 1884. Then Gilman C. Parker replaced him. During these years, the ship's home port changed several times. It eventually returned to Boston. There are no records of her voyages during this time. But one historian says Gove tried hard to make her successful.

In November 1884, Captain Parker worked with some Boston shippers. They filled the Mary Celeste with mostly worthless goods. But they said on the ship's papers that the cargo was valuable. They insured it for US$30,000. On December 16, Parker set sail for Port-au-Prince, Haiti. On January 3, 1885, the Mary Celeste neared the port. She went through a channel between Gonâve Island and the mainland. In this channel was a large, well-known coral reef called the Rochelois Bank. Parker purposely ran the ship onto this reef. It ripped open her bottom, damaging her beyond repair. He and the crew then rowed ashore. Parker sold the salvageable cargo for $500 to the American consul. He then tried to claim the insurance money for the alleged value.

The consul reported that what he bought was almost worthless. So, the ship's insurers started a full investigation. They soon found out the cargo was insured for too much. In July 1885, Parker and the shippers were tried in Boston. They were accused of planning to commit insurance fraud. Parker was also charged with "wilfully cast[ing] away the ship." This crime is called barratry. The trial for planning the fraud happened first. But on August 15, the jury could not agree on a verdict. Some jurors didn't want to affect Parker's upcoming trial for barratry. Instead of a costly new trial, the judge made a deal. The defendants dropped their insurance claims. They also paid back all the money they had received. The barratry charge against Parker was put off, and he was allowed to go free. But his reputation was ruined. He died poor three months later.

In August 2001, an expedition led by marine archaeologist Clive Cussler announced something. They said they found the remains of a ship on the Rochelois reef. Only a few pieces of wood and metal could be saved. The rest of the wreck was lost in the coral. Early tests on the wood showed it was the type used in New York shipyards. This was around the time of the Mary Celeste's 1872 repairs. It seemed the remains of the Mary Celeste had been found. However, tree-ring dating tests showed the wood came from trees that were still growing in 1894. This was about ten years after the Mary Celeste was wrecked. So, it was not the Mary Celeste.

Legacy and Remembrances

The Mary Celeste was not the first ship found strangely empty at sea. Other similar cases happened between 1840 and 1855. But the Mary Celeste is the one people remember most. Her name, or the misspelled Marie Celeste, is now known for unexplained desertion.

In October 1955, the MV Joyita, a motor vessel, disappeared in the South Pacific. It had 25 people on board. The ship was found a month later, empty and drifting. No one from the ship was ever seen again. An investigation could not explain what happened. This case is called a "classic marine mystery of Mary Celeste proportions."

The Mary Celeste story inspired two popular radio plays in the 1930s. There was also a stage play in 1949. Several novels have been written. They usually offer natural, not magical, explanations. In 1935, a British film company made The Mystery of the Mary Celeste. It starred Bela Lugosi as a sailor who goes crazy. It was not a big success. A 1938 short film, The Ship That Died, showed different ideas. These included a mutiny, fear of explosion from alcohol fumes, and supernatural causes.

In November 2007, the Smithsonian Channel showed a documentary. It was called The True Story of the Mary Celeste. It looked into many parts of the case but didn't offer a clear answer. One idea suggested problems with the ship's pumps and instruments. The Mary Celeste had carried coal, which creates a lot of dust. The pump was found taken apart on deck. So, the crew might have been trying to fix it. The ship's hold was full. The captain would not know how much water had entered during rough seas. The filmmakers also thought the clock used for navigation might have been wrong. Briggs might have thought they were close to Santa Maria. But they were actually 120 miles (190 km) farther west. This could have made him order everyone to leave.

In Spencer's Island, where the ship was built, there is a monument. It remembers the Mary Celeste and her lost crew. There is also an outdoor cinema shaped like the ship's hull. Gibraltar and the Maldives have issued postage stamps to remember the incident.

See also

- Ghost ship

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously at sea

- Abel Fosdyk papers

- J. Habakuk Jephson's Statement

Images for kids

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |