Mary Hinkson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mary De Haven Hinkson

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Mary De Haven Hinkson

March 16, 1925 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

|

| Died | November 26, 2014 (aged 89) New York, New York

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Wisconsin |

| Occupation | Dancer, choreographer |

| Spouse(s) | Julien Jackson; 1 child |

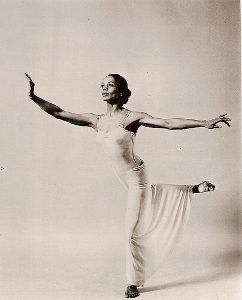

Mary De Haven Hinkson (March 16, 1925 – November 26, 2014) was an amazing African American dancer and choreographer. She broke barriers in the dance world, especially in modern dance and ballet. Mary is famous for her work with the Martha Graham Dance Company, one of the most important dance groups ever.

Contents

Mary Hinkson's Life and Dance

Early Life and School

Mary Hinkson was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1925. Her mother was a school teacher, and her father was a doctor. He was the first African American head of an army hospital. Mary learned about dance in high school. She took a class called eurythmics, which taught the Dalcroze technique. She also learned Native American dance forms at summer camp.

Mary didn't get formal dance training until she went to the University of Wisconsin. There, she studied with Margaret H'Doubler. Mary was very excited to learn from Doris Haywood at camp. She felt a strong passion for dance. Even though she was new to dance, she was encouraged to start pointe work.

In high school, Mary attended Philadelphia High School for Girls. It was a very traditional school. She learned gymnastics and competed in them. For a while, she thought this was what dance was all about.

In 1958, Mary and her husband, Julien Jackson, had a daughter named Jennifer. Mary passed away in Manhattan in 2014 at 89 years old.

College and Dance Training

When Mary started college at the University of Wisconsin, she tried new sports like basketball and soccer. She also took classes in English, French, history, zoology, and physical education. She did very well in all her subjects. Luckily, the university was one of the first to offer a real dance major. Mary changed her studies to focus on dance.

Margaret H’Doubler led the dance department. She loved teaching about how the body moves. She taught her students to explore their physical limits. Mary remembered an exercise where they created movements blindfolded. Then they recreated them standing up. Mary loved learning from Margaret and how she helped students find their own unique style.

Mary also learned from a teacher named Louise. Louise was trained by famous dancers Mary Wigman and Hanya Holm. Louise taught a flowing and internal style of dance. Mary never saw Louise dance fully, but she knew it was beautiful.

Mary joined a dance group called Orchesis. You had to audition to join. She felt nervous because other dancers had more experience. But she got in! In her first show, Orpheus and Eurydice, a local newspaper mentioned her and Matt Turney. They were the first African American members of the group. This was Mary's first time on a real stage. She felt focused and loved the warmth of the lights. Her teacher Louise noticed Mary's strong stage presence. After that, Mary felt much less nervous about performing.

Mary graduated in 1946. She continued her studies for another year. Then she became an instructor for the Department of Physical Education for Women. She was one of the first Black women to teach at a mostly white university.

At the University of Wisconsin, Mary faced segregation. African American students could enroll, but they were often kept out of school events. They were also not allowed in most dorms. Mary and Matt Turney lived at the Groves Women's Cooperative.

Becoming a Professional Dancer

Margaret H'Doubler encouraged Mary to see the Martha Graham Dance Company. They performed in Wisconsin in the 1940s.

During their junior and senior years, Mary and some friends formed the Wisconsin Dance Group. They traveled around the country in an old car. They performed dances they choreographed. Mary didn't choreograph much at first, but their shows were very popular. To keep the car running, each dancer paid $15 for gas and maintenance. They continued this after college.

To further their careers, they moved to New York. They hoped to train with Hanya Holm, but she wasn't teaching much. They decided to study at the Grand Studio.

In 1951, Martha Graham saw Mary and Matt's talent. Mary was chosen to perform in a demonstration by Martha Graham. She performed parts from Dark Meadows, Diversion of Angels, and Sarabande. Mary even filled in for a bigger role and performed with Bertram Ross. After this, Martha Graham recognized Mary's skills. She asked Mary to join the Martha Graham Dance Company. Mary joined in 1953. She also took experimental classes with another dancer named YURIKO.

In Mary's first official season with the company in 1952, Graham created a special role for her. It was in a piece called Canticle for Innocent Comedians. Graham made Mary get her own Dogwood branches for a prop. Mary found this difficult. Graham told her, "You must take responsibility for your own role." She meant that dancers should truly connect with their characters.

Early in her career, Mary didn't have much money. She earned money by giving private dance lessons. She also learned to teach. This led to a career as a teacher at places like Juilliard School of Music, Dance Theatre of Harlem, and the Ailey School.

Amazing Performances

Mary also worked with the New York City Opera. She auditioned for John Butler and was chosen. She later found out Butler had mixed her up with Matt Turney! Mary found the Opera to be more organized than the Martha Graham Dance Company. She said, "There was none of this chaos that we always had." From 1952 to 1953, Butler often took the opera to perform on NBC Sunday morning shows. The dancers became so good they did their own makeup. Sometimes, Doris Humphrey would watch and give feedback. Mary enjoyed balancing both companies. But Graham sometimes got upset about conflicting schedules.

In 1953, Mary became a principal dancer in Bluebeard’s Castle at the New York City Opera. She found this dance a bit scary. She was lifted high onto a 12-foot platform. In 1960, she also auditioned for Balanchine's Figure in the Carpet. She performed in many shows. However, she couldn't go on the company's Asian tour in 1956 because she was getting married.

In 1953, Mary took on the role of the woman in white in Heretic. She worried about living up to the previous dancer. Yuriko told her to make the role her own. Bob Cohen warned Mary not to let the part "destroy" her. When Graham wouldn't change a difficult knee drop, Yuriko helped Mary find a new movement. For a short time, Mary wore a pale pink costume for this role. But it was changed back to white after a critic called it "underwear pink."

The company then toured Europe from February to June. They traveled by boat, which was unusual for dance companies. Everyone had fun playing games. Graham, who was seasick, was annoyed by this. During practices, Graham worked them very hard in cold weather. They enjoyed the long breaks they sometimes got.

In England, Graham almost canceled a premiere because a piece wasn't finished. The producer wouldn't allow it. So, Mary and the company had to improvise and fill in the missing parts. This gave them a lot of practice at thinking quickly. They left England after three weeks with poor reviews. Mary felt this was partly because the audience focused on Graham's age instead of her performance.

The company was happy to arrive in the Netherlands because it was much warmer. The audience reaction was also very different. Sometimes, police had to hold back crowds trying to get in. They performed in lecture-demonstration formats. They did pieces like Letter to the World, Appalachian Spring, Diversion of Angels, and Canticle for Innocent Comedians. Mary was in many of these pieces. She also got to watch some from the audience with Turney.

Mary returned in August after traveling a bit longer in Europe. Friends from Jack Cole’s company wanted her to stay. But she came back to New York. Martha Graham wanted everyone to tour the Far East again. Mary refused to go. The company was away from late 1955 to 1956.

In 1955, Mary performed in Seraphic Dialogue, a work with many solos. She learned the role of the martyr. But late in the process, she was given the role of the warrior, replacing Helen McGehee. The solo was very strong and full of jumps. But Mary made it "more fragile and human and feminine." She showed that the warrior deeply feared what she had to do. Graham usually changed roles to fit the dancer. But for this one, she stuck to her original idea. The production was even rushed. Mary remembered, "Jessica was sewing seams on me in the wings when the music was playing and the curtain was up." Later, dancers wore simple costumes. This made sure their performances were judged, not their outfits. The role of the warrior changed over time, and Mary did not perform it again.

When Mary returned to Seraphic Dialogue in 1958, she took on the graceful role of the maid. The original maid, Patsy, taught her. Mary made sure to make this role unique. She tried "to work for a real frightened innocent element." She also combined terror with power for the warrior section.

Mary took on this role unexpectedly. She had planned to stay with her daughter instead of touring Israel. But Graham convinced her to go when another dancer became pregnant. Mary left her daughter with her mother for 6–7 weeks. Her mother didn't approve. Mary used the tour to overcome her fear of not being as good as previous dancers. Because of these challenges, Mary preferred when a piece was created just for her.

Some roles Mary found less rewarding were Athena and Iphigenia in Clytemnestra. She found it hard to connect with the piece. She also didn't like all the sitting and watching involved. Dancing the Furies was much more fun for her. The original ending, with dancers holding a stoll above their heads, had a powerful, dark effect. When learning Iphigenia, she was taught by Yuriko, who had quick, sharp movements. Mary preferred learning from Natanya Neumann, who focused more on musicality, like herself.

When Mary learned the role of Clymenestra, she and Graham worked from films. It was hard because the movements were mirrored, the film was sped up, and the music was silent. Their pianist helped them match the movement to the music. They also struggled with Graham's changes to the choreography over the years. Mary relied on notes in the margins of the sheet music. To understand the character, Mary thought about how the character changed from the beginning to the end of the piece.

About performing as Medea in Cave of the Heart, Mary said, "We must realize that it's a woman scorned, but first she was a woman in love." She felt that playing Medea as a witch from the start would miss the point. Learning this piece from film was also hard because there were no notes. Mary became very emotional in the dance. She only performed it twice. But Martha Graham complimented her on how she used the music.

Mary performed as Eve in Embattled Garden in 1958 with Bertram Ross as Adam. Later, she performed as Lilith opposite Bob Cohan’s Adam. She learned that some roles shouldn't be taken too seriously. She said, "You have to dance it, really dance it, go with it, and give it flight."

During one season of Embattled Garden, Graham used alternate dancers. Mary was one of them. Yuriko, Mary Hinkson, and the other alternate, Linda, were called "the three faces of Eve" by Bertram Ross. This system was rare. Graham didn't always participate physically, so coordinating many people was difficult for her. The downside of being an alternate was getting less rehearsal time.

Graham choreographed a role specifically for Mary in Circe. This hadn't happened since Canticle for Innocent Comedians. Graham used this as a way to get Mary to tour with them again. Mary was hesitant to leave her daughter, but the offer worked. Martha Graham had originally planned the role for herself. Mary learned the character from Graham's descriptions of animal-like movements. She tried to make her performance feel like an animal's instincts. She also wanted to show Circe as a tricky enchantress. Playing Circe helped Mary learn how to interact with other performers. During rehearsals for Circe, Mary noticed Graham became less reliable. When the piece was finally performed, Yuriko helped Mary create a memorable hairstyle. It was so complex that Mary couldn't perform in other pieces during the shows.

Circe premiered in London. It wasn't completely finished for the first show. So, Mary and the company were frantically finishing costumes and choreography at the last minute. The audiences loved the piece. It came alive on stage in a way it never did in rehearsal. Mary realized they had to trust their animal instincts and be as dramatic as possible.

Mary took classes in many places, including with Louis Horst. He liked her so much that he took her to demonstrate for him at high school performing arts programs.

Mary, Bertram Ross, and Bob Cohan led the revival of Dark Meadow. They used old films for the duets. For the solos, they relied on Yuriko’s memory. When Mary first saw Dark Meadow as an audience member, she didn't fully understand it. But performing it gave it new meaning. She felt "put in touch with some unknown ancestors." It was a "remarkable experience" and felt like a ritual. The hardest part was making sure the dance was more than just movements. This piece and its music were almost a religious experience for Mary.

Mary also danced in Deaths and Entrances. She remembered how her relationship with Graham grew during rehearsals. It was a tough piece. Even though Mary made progress, it looked shaky for a while. They premiered it at the Blossom Festival with the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra playing live.

Of all her roles, Mary liked the ones that flowed continuously. When a piece had many stops and starts, she found it less fulfilling. In Embattled Garden, there were breaks, but everyone was always involved. Diversion of Angels was more fragmented, but Mary still considered it nonstop. In Circe, dancers were on stage almost all the time. In Seraphic Dialogue, it wasn't as satisfying because there were uncomfortable poses where they had to stop. Mary said, "There's no denying that the best training in the world is to actually perform." She gained this experience throughout her career.

Mary performed in many pieces, including: Bluebeard's Castle, Clytemnestra, Deaths and Entrances, Cave of the Heart, Ardent Song, Seven Deadly Sins, Acrobats of God, Phaedra, Canticle for Innocent Comedians, Carmina Burana, Mythical Hunters, The Figure in the Carpet, Secular Games, and Circe.

Leaving the Martha Graham Company

Mary's decision to leave the company wasn't due to one event. It was many things over time. It started with an 18-month period where Graham was often sad, drinking, and not communicating well. Mary and Bertram Ross didn't want the company to fail. So, they worked to bring in new dancers and improve programs. They held auditions and offered young dancers $100 a week. They hoped to teach them hard work. It was rewarding to see some succeed, even if many weren't very committed. When Graham was away or in the hospital, Mary and Ross would visit her. They talked about everything except the company. Graham never acknowledged their efforts to Mary directly.

After their last series of works, Mary visited Europe in the summer of 1972. She had surgery for a torn meniscus. When she returned, Graham wanted Mary and Turney to help her remove some leaders from the company. They didn't want to do this. Around this time, a new associate director, Ron Protas, quickly became close to Graham.

Another problem arose over showing the Martha Graham Dance Company on a mixed bill. Graham had always avoided this. She accused Mary of trying to harm her. Graham removed the company from the event. This caused problems for both them and the City Center.

To reach more people, the company toured many schools. After an error with earnings records, Graham started blaming people. No legal accusations were made, and it was resolved. But Graham didn't forget it.

Mary then took some new dancers on a residency. She had positive phone calls with Graham, discussing their performances. This residency and their Broadway opportunities were widely publicized by Tom Carrigan.

It became harder to work with Ron Protas. He fired people, kept Mary from Graham, and messed up her efforts to build good relationships with residencies. He also mismanaged performances and teaching opportunities. He tried to get everyone to tour again. But Mary heard it was triple cast, meaning three dancers for each role. She decided she would rather stay in New York and teach.

After Bertram Ross resigned, Mary went to Graham. Graham was barely present and on pain medication. Mary said, "I was wanting out only I had not totally come to grips with it. The situation was unbearable."

The situation got worse. Mary was promised that Bertram Ross would be rehired, and their contracts would be signed on the same day. But Mary's contract wasn't ready. Graham scolded Mary for it. They had a big argument. Mary left the Martha Graham Dance Company at 48 years old. She didn't look back and felt relieved.

About her time at the company, Mary said, "It was never a bed of roses to work there but at least you always had this belief, this respect for the end product and theater experience." She left because she lost this feeling. Even though she left on a bad note, she felt her earlier knee injury made her appreciate the gift of being there. To keep dance in her life, she continued to teach and perform in smaller shows.

Teaching and Choreography

Throughout her career, Mary Hinkson worked with many famous dancers and choreographers. These included Harry Belafonte, Alvin Ailey, Pearl Lang, Walter Nix, John Butler, Martha Graham, Glen Tetley, and Merce Cunningham.

Working with Tetley was different. He didn't often ask dancers to improvise for inspiration. He started ideas without forcing specific movements. Working with him was challenging but enjoyable. Mary often dreaded practices at Graham's company. But she woke up excited for fun rehearsals with Tetley. His movements were more about suggestion, but he still wanted drama.

Mary also taught at the Juilliard School of Music, Dance Theatre of Harlem, and the Ailey School.

Relationship with Martha Graham

Mary Hinkson and Martha Graham’s relationship had good and bad times. At their best, they had meaningful talks during rehearsals. Sometimes Martha even gave Mary rare compliments on her dancing. Other times, they argued about re-choreographing dances. Graham also didn't like Mary taking other opportunities outside the company. Mary respected Graham's talent, wisdom, and methods. But she sometimes disliked how Graham spoke to her. Mary mostly put up with their arguments. But sometimes she would respond with her own attitude. When Mary took other jobs or stood up for herself, Graham would often yell at her or stop her from performing in certain works.