Mingo Oak facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mingo Oak |

|

|---|---|

The Mingo Oak, photographed in the 1930s

|

|

| Species | White oak (Quercus alba) |

| Coordinates | 37°49′7″N 82°3′42″W / 37.81861°N 82.06167°W |

| Date seeded | Estimated between 1354 and 1361 AD |

| Date felled | September 23, 1938 |

| Custodian | Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust Island Creek Coal Company North East Lumber Company West Virginia Game, Fish, and Forestry Commission |

The Mingo Oak was a giant white oak tree that grew in West Virginia, United States. It was also known as the Mingo White Oak. People first noticed how old and big it was in 1931. The Mingo Oak was the oldest and largest living white oak tree in the world until it died in 1938.

This amazing tree stood in Mingo County, West Virginia. It was in a small valley called a cove, at the bottom of Trace Mountain. This area was near the start of a stream called Trace Fork, which flows into Tug Fork. The Mingo Oak was super tall, reaching over 200 feet (61 m) high. Its main trunk was 145 feet (44 m) tall before it branched out.

The tree's top part, called its crown, was 130 feet (40 m) wide and 60 feet (18 m) tall. The trunk itself was about 9 feet 10 inches (3.00 m) across. The distance around its base was 30 feet 9 inches (9.37 m). Experts thought the tree could have produced enough wood for 15,000 feet (4,600 m) to 40,000 feet (12,000 m) of lumber. When the tree was cut down in 1938, it was estimated to weigh around 5,400 long tons (5,500 t).

Even though people knew the tree was big, its special status wasn't fully known until 1931. That's when John Keadle and Leonard Bradshaw measured it. They found it was the biggest living white oak in the world! Scientists believe the Mingo Oak started growing between 1354 and 1361 AD. The Smithsonian Institution studied samples from the tree. They confirmed it was the oldest tree of its kind.

Companies that owned the land, like Island Creek Coal Company, helped protect the tree. They leased about 1.5 acres (0.61 ha) of land around the tree to the West Virginia Game, Fish, and Forestry Commission. This meant the area would be a state park for as long as the tree lived. The commission cleared the land and added things like seats and picnic areas for visitors.

By the spring of 1938, the Mingo Oak didn't grow any leaves. In May of that year, West Virginia's state forester, D. B. Griffin, announced the tree had died. The most common idea is that the tree died from harmful gases. These gases and sulfur fumes came from a burning pile of coal waste nearby. The tree was cut down on September 23, 1938, with a big ceremony. Parts of the tree were sent to the Smithsonian Institution and the West Virginia State Museum. After the tree was felled, the land went back to the Island Creek Coal Company.

Contents

Where the Mingo Oak Grew

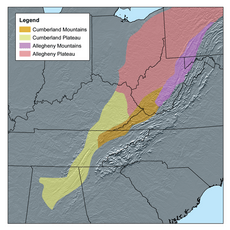

Before European settlers arrived, the Allegheny Plateau in West Virginia was covered in ancient forests. These forests had many deciduous trees, mostly oaks and chestnuts. The small valleys, or coves, in the Appalachian Mountains had been untouched for about 300 million years. The wet ground and deep soil in these coves helped many different kinds of trees grow.

The biggest trees in these old forests were white oaks (Quercus alba). They often grew over 100 feet (30 m) tall and 6 feet (1.8 m) wide. White oaks grow across most of the Eastern United States. But they grow best on the western slopes of the Appalachian Mountains. According to botanist Earl Lemley Core, white oaks do well on the northern sides of mountains and in coves. Coves are small valleys between two ridges. White oaks also like moist lowlands and uplands, as long as the soil isn't too dry or shallow.

The Mingo Oak stood in one of these perfect coves. It was at the base of Trace Mountain, near the start of Trace Fork. This stream flows into Tug Fork. The tree was close to Holden, about 10 miles (16 km) from Logan. It was also about 1 mile (1.6 km) from the Logan County line in Mingo County. The tree got its name from Mingo County. The county was named after the Mingo Iroquois people. A famous Native American leader named Logan was connected to the Mingo people. Holden was also where the Island Creek Coal Company had its main office. This company leased the land where the Mingo Oak grew.

How Big and Old Was It?

The Mingo Oak was the largest of the giant white oaks that once filled West Virginia's old forests. After a survey of white oaks across the country, it was found to be the biggest living white oak in the United States, and in the world. The next biggest white oak was in Stony Brook, New York. It had a wider base but was much shorter, only 86 feet (26 m) tall.

With its top branches, the Mingo Oak reached over 200 feet (61 m) high. Its main trunk, or bole, was 145 feet (44 m) tall before it split into branches. The tree's crown was 130 feet (40 m) wide and 60 feet (18 m) tall. The trunk was 9 feet 10 inches (3.00 m) across. The distance around its base was 30 feet 9 inches (9.37 m). At 4.5 feet (1.4 m) from the ground, its circumference was 19 feet 9 inches (6.02 m). Since the old forest around it had been cut down, the Mingo Oak stood tall above the newer, smaller trees.

In 1931, lumber experts thought the tree could produce between 35,000 feet (11,000 m) and 40,000 feet (12,000 m) of lumber. This wood would have been worth about $1,400. In 1932, Perkins Coville of the United States Forest Service estimated the tree had 20,000 feet (6,100 m) of lumber. By 1938, engineers from the Island Creek Coal Company thought the trunk held 15,000 feet (4,600 m) of lumber. After the tree was cut down in 1938, it was estimated to weigh around 5,400 long tons (5,500 t).

Scientists believe the tree started growing sometime between 1354 and 1361 AD. The Smithsonian Institution used samples from the tree to confirm it was the oldest of its kind. In 1932, West Virginia state forester D. B. Griffin and Emmett Keadle used a special tool called an increment borer. They estimated the tree began growing around 1356, with a possible error of 25 or 30 years. Blueprints and samples were sent to the West Virginia State Museum and the Smithsonian Institution.

Protecting the Giant Tree

The land around the Mingo Oak was owned by the Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust. They leased the right to cut timber to the North East Lumber Company. This company only paid for the wood they actually cut. They found the Mingo Oak was too big to cut down, and it would cost too much to remove. The Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust also leased the land to the Island Creek Coal Company for mining.

The area around the tree continued to be developed. A highway connecting Logan to Williamson was built near the Mingo Oak. Even though the tree was known for its size, its special status wasn't fully recognized until 1931. That's when John Keadle and Leonard Bradshaw measured it and found it was the largest living white oak in the world. After this discovery, the Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust and the Island Creek Coal Company agreed to give the property to the state of West Virginia.

In late 1931, Emmett Keadle wrote to Governor William G. Conley. He told the governor how important the tree was and that the companies were willing to lease the land to the state. Governor Conley suggested the companies lease the land to the West Virginia Game, Fish, and Forestry Commission.

The Island Creek Coal Company, the North East Lumber Company, and the Cole and Crane Real Estate Trust leased about 1.5 acres (0.61 ha) around the tree to the commission. The plan was for it to be a state park for the tree's whole life. The commission cleared plants around the tree and built a fence. They also built a bridge over Trace Fork so visitors could reach the park from the highway. The state added cooking ovens, picnic tables, and benches.

Because of its huge size and age, the Mingo Oak became a special place. It even became a place for worship. A pulpit and benches were built under its branches. During the summer, preachers gave outdoor sermons there. The Mingo Oak also helped people learn about protecting nature. It became a popular spot for visitors. Groups like the West Virginia Parent-Teacher Association visited the tree in 1933.

The Tree's Death

In the summer of 1937, the Mingo Oak barely grew any leaves, only on a few branches. In February 1938, biologist Earl M. Vanscoy wrote that the tree was "almost dead." He believed it was due to poisonous gases and sulfur fumes. These came from a burning pile of coal waste from the Island Creek Coal Company nearby. By the spring of 1938, the tree didn't produce any leaves at all. White oaks usually grow flowers and leaves between late March and late May.

On May 4, 1938, West Virginia's state forester, D. B. Griffin, announced that the Mingo Oak had died. Griffin also noted that a fungus that only grows on dead or dying trees had been on the Mingo Oak for months. The main idea is that the tree died because it was suffocated by fumes from the burning coal waste. However, local news at first reported that a fungus killed the tree.

Cutting Down the Mingo Oak

To prepare for cutting the tree, some initial cuts were made on its north side on September 22. This was done to control where the tree would fall. It also helped estimate how long it would take to cut through the rest of the trunk. After cutting about 2 feet (0.61 m) into the trunk, they found that the tree was rotting and hollow in the center. The lumber crews adjusted their cut, and decided to finish the job the next morning.

The tree was cut down on September 23 during a ceremony. Between 2,500 and 3,000 people attended. Important people were there, including state forester D. B. Griffin and the president of the Island Creek Coal Company, E. P. Rice. Representatives from other companies that owned the land were also present. Besides regular cameras, two movie cameras filmed the event. Police and park rangers were there to keep things safe and direct traffic.

Two expert lumbermen, Paul Criss and Ed Meek, were brought in to help cut down the tree. Criss brought a team of woodchoppers and sawyers. Meek came with his own crew. Griffin also got help from game wardens and rangers. A nearby Civilian Conservation Corps camp also sent a team to help. A special 9-foot (2.7 m) saw was used. Most regular crosscut saws were only 6 feet (1.8 m) long, which wasn't enough for the Mingo Oak's wide trunk.

Before the cutting began, Criss jokingly shaved Meek's face with his axe. He commented, "That's the trouble with having a lot of officials around. I've shaved a thousand men with that axe and that's the first time I ever drew blood. These officials get me a little nervous."

By 9:00 AM, hundreds of people had arrived. At 10:00 AM, the final cutting started. Criss decided to make the tree fall downhill onto a narrow ledge. Even though the ledge wasn't long enough, everyone agreed the tree's rotten top would break anyway. Criss told the crews, "I can put her anywhere you want her gentlemen. Lay a $10 bill anywhere you like and I'll guarantee the trunk will cover it."

Six men operated the 9-foot (2.7 m) saw across the trunk. As the saw cut deeper, bystanders were moved to a safe spot up the hillside. The men pushed the saw back and forth, while woodchoppers widened the cut. After about 30 minutes, Criss yelled, "We're through boys." The men removed the saw, and the woodchoppers continued. The tree made a crackling sound, its top branches dipped, and then the Mingo Oak crashed down. It was supposed to be down by 10:30, but it fell at 11:00 AM. To help cut the fallen tree into pieces, there were woodchopping and log sawing contests.

Because the tree's base was very rotten, the lowest 24 feet (7.3 m) of the trunk was useless. However, 66 feet (20 m) of the trunk was saved in one piece. Another cut produced a 40-foot (12 m) log, which was about 54 inches (140 cm) wide. The Island Creek Coal Company sent the 66-foot (20 m) log to a lumber plant in Rainelle. This plant had the largest saw in the Eastern United States. From this log, cross-sections were cut. Other parts were made into lumber, tabletops, and souvenirs. Various pieces of the tree were given to the West Virginia State Museum and the Smithsonian Institution.

The Mingo Oak's Legacy

The Mingo Oak was the largest living white oak. Except for the state's box huckleberries (Gaylussacia brachycera), it was the oldest living plant in West Virginia. People called the tree the "mighty monarch of the mountains." Biologist Earl M. Vanscoy said it was "perhaps West Virginia's most remarkable tree." Colby B. Rucker of the Native Tree Society called the Mingo Oak an "exceptional forest giant."

When the Mingo Oak died and was cut down, the land lease for the state park ended. The land around the tree went back to the Island Creek Coal Company.

In 1940, a club of whittlers made a gavel from a piece of the Mingo Oak. They gave it to federal judge Harry E. Atkins. Some of the club members had been on juries in his court. They gave him the gavel to show their thanks.

The West Virginia Division of Culture and History placed a historic marker near where the Mingo Oak stood. This marker was part of the West Virginia Highway Historical Marker Program. It has since gone missing. The marker read:

The largest white oak in the United States when it died and was cut down, 9-23-1938. Age was estimated to be 582 years. Height, 146 feet; circumference, 30 feet, 9 inches; diameter, 9 feet, 9 1/2 inches. Trunk contained 15,000 feet B. M. lumber.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |