Nancy Roman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

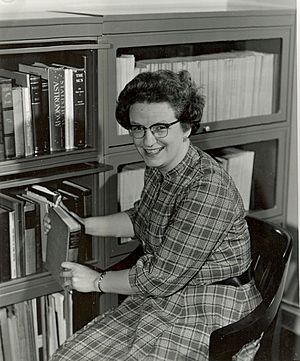

Nancy Roman

|

|

|---|---|

Roman in 2015

|

|

| Born |

Nancy Grace Roman

May 16, 1925 Nashville, Tennessee, U.S.

|

| Died | December 25, 2018 (aged 93) Germantown, Maryland, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Swarthmore College, University of Chicago |

| Known for | NASA's Chief of Astronomy Planning of the Hubble Space Telescope |

| Awards | Federal Woman's Award Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal, NASA NASA Outstanding Scientific Leadership Award |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Institutions | Yerkes Observatory, University of Chicago, NASA, Naval Research Laboratory |

| Thesis | Ursa Major Moving Group (1949) |

| Doctoral advisor | William Wilson Morgan |

| Other academic advisors | W.W. Morgan, Peter van de Kamp |

Nancy Grace Roman (born May 16, 1925 – died December 25, 2018) was an American astronomer. She made important discoveries about how stars are grouped and move. She was the first woman to hold an executive position at NASA. Roman served as NASA's first Chief of Astronomy during the 1960s and 1970s. She is known as one of the "visionary founders of the US civilian space program."

Nancy Grace Roman created NASA's space astronomy program. Many people call her the "Mother of Hubble" because she played a key role in planning the Hubble Space Telescope. Throughout her career, Roman also spoke publicly and taught. She encouraged women to pursue science careers.

On May 20, 2020, NASA named a new telescope after her. It is now called the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. This was done to honor her lasting contributions to astronomy.

Contents

Early Life and Passion for Stars

Nancy Grace Roman was born in Nashville, Tennessee. Her mother, Georgia Frances Smith Roman, was a music teacher. Her father, Irwin Roman, was a physicist and mathematician. The family moved often because of her father's jobs. They lived in Oklahoma, Houston, Texas, New Jersey, Michigan, and Nevada. When Nancy was about 12, they moved to Baltimore, Maryland. Her father became a Senior Geophysicist there. Nancy felt her parents greatly influenced her interest in science.

When Nancy was 11, she started an astronomy club. She and her classmates met weekly to learn about constellations from books. Even though some people tried to discourage her, Nancy knew by seventh grade that she wanted to dedicate her life to astronomy. She went to Western High School in Baltimore. She was in a special program and finished high school in three years.

Education and Early Career

College Years at Swarthmore

Roman attended Swarthmore College to study astronomy. The dean of women there was not very supportive of her choice. Nancy said the dean would "have nothing more to do with you" if you chose science or engineering. But the dean did send her to the astronomy department. The head of the department, Peter van de Kamp, taught her astronomy.

Nancy worked on two student telescopes that were not working. She said this helped her "get a feel for instruments." In her second year, she started working at the Sproul Observatory. She processed astronomical photographic plates. This meant working with old photos of the sky. She learned about professional astronomy by using the library. She graduated in February 1946. Van de Kamp suggested she continue her studies at the University of Chicago.

Graduate Studies at Chicago and Yerkes

Nancy started graduate school at the University of Chicago in March 1946. She found the classes easier than Swarthmore. She asked three professors for observation projects. One professor, William Wilson Morgan, gave her a project using a 12-inch telescope. She earned her Ph.D. in astronomy in 1949. Her main research was on the Ursa Major Moving Group.

After graduating, she worked at Yerkes Observatory for six years. She often traveled to the McDonald Observatory in Texas. Her research at Yerkes focused on studying different types of stars. She looked at F and G type stars and fast-moving stars. Her work led to some very important papers. She eventually left the university. There were not many permanent research jobs for women at that time.

Groundbreaking Research and Discoveries

Nancy Roman studied many stars similar to our Sun. She found that they could be sorted into two groups. These groups were based on their chemical makeup and how they moved in the galaxy. One of her discoveries was that stars made of hydrogen and helium move faster. Stars with heavier elements move slower.

She also found that not all common stars were the same age. She proved this by comparing hydrogen lines in their light. Roman noticed that stars with stronger lines moved closer to the center of the Milky Way. Other stars moved in more oval-shaped paths, away from the galaxy's main plane. These observations were key to understanding how our galaxy formed. Her paper on this topic was chosen as one of the 100 most important papers in 100 years by the Astrophysical Journal.

While at Yerkes Observatory, Roman observed the star AG Draconis. She accidentally discovered that its light pattern had completely changed. She said this discovery was lucky. The star is in that changed state only 2-3% of the time. This discovery greatly increased her reputation in astronomy.

In 1955, she published a catalog of fast-moving stars. It listed new types of stars and their properties. Her "UV excess" method became popular. It helped astronomers find stars with heavier elements just by looking at their colors. In 1959, Roman also wrote about how to find planets around other stars.

Joining the Space Program

After leaving the University of Chicago, Roman joined the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) in 1954. She worked in the new field of radio astronomy. At that time, NRL had the largest radio telescope in the US. Roman's work at NRL included radio astronomy and geodesy (studying Earth's shape). She even studied how sound travels underwater.

She spent three years at NRL. She became head of the microwave spectroscopy section. She was one of the few people at NRL with a background in classical astronomy. This meant she was asked for advice on many topics. During her time at NRL, she helped with the Project Vanguard satellite program. This introduced her to space astronomy. She saw the great potential of doing astronomy from space.

Roman's radio astronomy work included mapping parts of the Milky Way galaxy. She also helped use radio astronomy for geodesy. This included using radar to measure the distance to the Moon more accurately. In 1959, she said this was the best way to find the Earth's mass.

In 1956, Roman was invited to speak in Armenia, which was part of the Soviet Union. She was the first civilian to visit the country after the Cold War began. This made her well-known internationally and in the United States. Her reputation grew, especially with people at the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

Becoming NASA's Chief of Astronomy

At a lecture, Jack Clark from NASA asked Roman if she knew anyone who wanted to create a space astronomy program. She saw this as an invitation to apply herself. She accepted the job. She knew it meant giving up some of her own research. But she said, "the chance to start with a clean slate to map out a program that I thought would influence astronomy for fifty years was more than I could resist."

Roman started at NASA in February 1959. She became Head of Observational Astronomy. In early 1960, she became the first astronomer to be Chief of Astronomy in NASA's Office of Space Science. She was also the first woman to hold an executive position at NASA.

Part of her job was traveling around the country. She gave lectures at astronomy departments. She told them about NASA's plans and opportunities. She also wanted to know what other astronomers wanted to study from space. Her visits helped turn ground-based astronomers into supporters of space astronomy. She made sure that major astronomy projects would be managed by NASA for all scientists.

From 1959 through the 1970s, Roman was the only person who approved or rejected proposals for NASA astronomy projects. She based her decisions on their quality and her own knowledge.

Pioneering Space Telescopes

In 1959, Roman suggested that we could find planets around other stars using a space telescope. She even proposed a method for it. A similar method was later used by the Hubble Space Telescope. It will also be used by the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope to image exoplanets. She also believed that the future Hubble telescope could find Jupiter-like exoplanets. This was proven true in 2002.

Roman was Chief of Astronomy and Solar Physics at NASA from 1961 to 1963. She oversaw the development of the Orbiting Solar Observatory (OSO) program. OSO 1 was launched in 1962. She also held other roles, including Chief of Astronomy and Relativity.

From 1959, she also led the orbiting astronomical observatories (OAO) program. These were optical and ultraviolet telescopes. The first one, OAO-1, failed after three days in orbit in 1966. But she continued to develop Orbiting Astronomical Observatory 2. It launched in December 1968 and became the first successful space telescope. OAO-3, named Copernicus, worked from 1972 to 1981.

Roman also oversaw the development of three smaller astronomy satellites:

- The X-ray explorer Uhuru (satellite) in 1970.

- The gamma-ray telescope Small Astronomy Satellite 2 in 1972.

- The X-ray telescope Small Astronomy Satellite 3 in 1975.

She also planned other programs, like the Astronomy Rocket Program. Roman was known for being direct in her decisions. She would approve or deny projects based on their merit.

Roman also helped set up NASA's scientific ballooning program. She led the development of NASA's airborne astronomy program. This started with a telescope in a Learjet in 1968. Then came the Kuiper Airborne Observatory in 1974. This opened up the infrared part of the spectrum for astronomers. Other long-wavelength missions started during her time. These included the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) and the Infrared Astronomy Satellite. COBE later won a Nobel Prize for two of its scientists. Roman also helped NASA join the International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE) project. She felt this was her greatest success.

The "Mother of Hubble"

The last major program Roman was involved with was the Hubble Space Telescope. It was first called the Large Space Telescope (LST). An astronomer named Lyman Spitzer had suggested a large telescope in space in 1946. Roman decided to develop smaller OAO telescopes first. This was to test the necessary technologies. She felt that even the small 12-inch telescopes of OAO-2 were a big step forward. This was because developing good pointing systems was a huge challenge.

After OAO-2 was successful, Roman started to consider the Large Space Telescope. She gave public talks about how valuable such a telescope would be. In 1971, Roman set up the Science Steering Group for the Large Space Telescope. This group included NASA engineers and astronomers from all over the country. Their goal was to design a space observatory that met the community's needs and was possible for NASA to build.

Roman was very involved in the early planning of Hubble. She helped set up how the program would work. Many people say she was the main force behind the LST from the beginning. She worked with the astronomy community to create a plan for how NASA would run large science projects. This plan is now a standard for big astronomy facilities. She also helped create the Space Telescope Science Institute.

Roman then spoke to politicians to get support for the LST project. She also wrote statements for Congress throughout the 1970s to justify the telescope. She invested in new detector technology. This led to Hubble being the first major observatory to use Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) detectors. Roman's final role in Hubble was serving on the selection board for its science operations.

Because of her contributions, she is often called the "Mother of Hubble." Later in life, she said she was uncomfortable with this name. She felt many others also contributed greatly. Edward J. Weiler, NASA's Chief Astronomer, called her "the mother of the Hubble Space Telescope." He said, "it was Nancy... who really helped to sell the Hubble Space Telescope, organize the astronomers, who eventually convinced Congress to fund it."

Life After NASA and Legacy

After working for NASA for 21 years, Nancy Roman retired early in 1979. She wanted to care for her elderly mother. But she continued as a consultant for another year to finish the selection of the Space Telescope Science Institute. Roman was interested in learning computer programming. She took a course and then worked as a consultant for a company called ORI, Inc. from 1980 to 1988. In this role, she supported research in geodesy and astronomical catalogs.

This led to her becoming the head of the Astronomical Data Center at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in 1995. She continued this work until 1997. After that, Roman spent three years teaching science to junior high and high school students. She also taught K-12 science teachers, especially in areas that needed more support. Then, for ten years, she recorded astronomy textbooks for Reading for the Blind and Dyslexic. In a 2017 interview, Roman said, "I like to talk to children about the advantages of going into science and particularly to tell the girls, by showing them my life, that they can be scientists and succeed."

From 1955 on, she lived in the Washington, D.C. area. Later, she lived in Chevy Chase, Maryland with her mother, who passed away in 1992. Outside of work, Roman enjoyed going to lectures and concerts. She was active in the American Association of University Women. Nancy Grace Roman died on December 25, 2018, after a long illness.

Supporting Women in Science

Like many women in science in the mid-20th century, Roman faced challenges. Science and technology were mostly dominated by men. People often discouraged her from going into astronomy. In an interview, Roman remembered asking her high school counselor if she could take second-year algebra instead of Latin. She recalled, "She looked down her nose at me and sneered, 'What kind of lady would take mathematics instead of Latin?' That was the sort of reception I got most of the way."

At one point, she was one of very few women in NASA. She was the only woman in an executive position. She took courses called "Women in Management" to learn about being a woman in a leadership role. However, she found these courses disappointing. They focused more on women's interests than on the problems women faced in management. In 1963, when only men could become astronauts, Roman said she believed there would be women astronauts someday. But she regretted that she could not change this policy herself.

Because she helped advance women in science management, Roman received awards from several women's organizations. These included the Women's Education and Industrial Union and Women in Aerospace. She was also one of four women featured in the "Women of NASA LEGO Set" in 2017. She described this as "by far the most fun" of all her honors.

Awards and Honors

- Federal Woman's Award – 1962

- One of 100 Most Important Young People, Life magazine – 1962

- Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal NASA – 1969

- NASA Outstanding Scientific Leadership Award – 1978

- Fellow, American Astronautical Society – 1978

- William Randolph Lovelace II Award, American Astronautical Association – 1979 & 2011

- Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science – 1988

- Lifetime Achievement Award – Women in Aerospace – 2010

- Woman of Distinction from American Association of University Women, Maryland – 2016

- Honorary Doctorates from Russell Sage College (1966), Hood College (1969), Bates College (1971) and Swarthmore College (1976)

- The asteroid 2516 Roman is named in her honor.

- NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Technology Fellowship in Astrophysics is named for her.

- In 2017, a "Women of NASA" LEGO set included mini-figurines of Roman, Margaret Hamilton, Mae Jemison, and Sally Ride.

- Episode 113 of the "Hubblecast" podcast, "Nancy Roman – The Mother of Hubble," was made in her honor.

- In 2020, NASA named the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope in her honor.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Nancy Roman para niños

In Spanish: Nancy Roman para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |