Niños de Rusia (Children of Russia) facts for kids

The Niños de Rusia (which means "Children of Russia" in Spanish) were nearly 2,900 children who were sent to the Soviet Union during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). The government of the Second Spanish Republic evacuated these children in 1937 and 1938 to keep them safe from the dangers of the war. Many Spanish children were also sent to other countries during this time, and they are often called Niños de la Guerra (Children of War).

When they first arrived, the Niños were welcomed warmly in the Soviet Union. However, their lives changed when the Soviet Union joined World War II and was invaded by Nazi Germany. The children faced the hardships of war again. Because of political differences, those who returned to Spain later were sometimes viewed with suspicion by the Spanish government.

Some of the Niños de Rusia came back to Spain between 1956 and 1959. Others moved to Cuba in the 1960s. A large number of them stayed in Russia and made it their home. In 2004, about 239 Niños de Rusia were still living in the areas that used to be the Soviet Union.

Contents

Evacuating Children from War

As the Spanish Civil War continued, life became very difficult in the areas controlled by the Republican government. To protect children from the fighting, they were sent to other countries. A special group called the National Council for Evacuated Children helped organize these trips.

Many countries took in Spanish children:

- France welcomed about 20,000 children.

- Belgium took 5,000.

- The United Kingdom received 4,000.

- Switzerland took 800.

- Mexico welcomed 455.

- Denmark took 100 children.

Between 1937 and 1938, four groups of Niños, totaling 2,895 children (1,197 girls and 1,676 boys), were sent to the Soviet Union. These evacuations, mainly from Valencia and Barcelona, were planned by the Spanish Republic, the Soviet Union, and the International Red Cross. Children and their adult helpers were chosen after public announcements.

Sometimes, the evacuations had to happen very quickly because Francisco Franco's Nationalist troops were getting close. This led to some confusion, and a few children got lost or ended up in the Soviet Union when their parents thought they were going to France.

Most of the evacuated children came from the Basque Country, Asturias, and Cantabria. These areas had been cut off from the rest of the Republic by Franco's forces. Many children traveled on merchant ships, often crowded together. The agreement with the Soviet Union said children should be between five and twelve years old. However, some children were actually younger (around 3) or older (up to 14). A small group of adults, aged 19 to 50, went with them to care for them and continue their schooling.

The Children's Houses

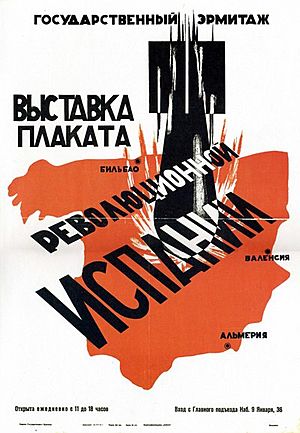

When some of the evacuated children arrived in Leningrad, they received a festive welcome. The Soviet Union saw the Niños as a symbol of their support against fascism in Spain. Soviet officials made sure the children had good hygiene, food, and health care.

The children were placed in special homes called "Casas de Niños" (Children's Houses). Some of these were grand buildings that had been taken over during the October Revolution. In these houses, the Niños were cared for and educated. They were mostly taught in Spanish by Spanish teachers, but they followed the Soviet education system. The children and their families believed their stay in Russia would be short. Many later said they were excited about the adventure of traveling to a new country.

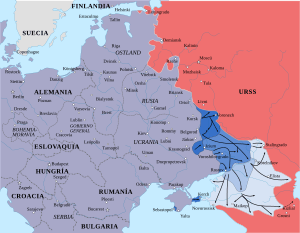

By the end of 1938, there were sixteen Niños houses in the Soviet Union. Eleven were in what is now Russia, including one in Moscow and two near Leningrad (in Pushkin and Obninsk). Five were in Ukraine, including homes in Odessa, Kiev, and Yevpatoria. Most Niños remember their time in these Children's Houses as a happy period where they received a good education.

Life During World War II

The lives of the Niños changed when World War II began. The Soviet Union's interest in the Niños lessened after the Spanish Civil War ended. Also, a non-aggression agreement between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany (the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact) was signed in August 1939. This pact ended in June 1941 when Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

The Niños houses had to be closed because of the danger from the Nazi invasion. The German army surrounded Leningrad and moved toward Moscow and into Ukraine, putting all the areas where the Spanish children lived at risk. The Niños in Leningrad endured the city's siege during the harsh winter of 1941-1942. About 300 children were later evacuated by crossing the frozen Lake Ladoga in trucks.

Gradually, the Niños houses were moved to safer, often very remote, areas near the Ural Mountains and Central Asia. Life in this "second exile" became much harder. Many children got sick or died from diseases like tuberculosis and typhus, along with extreme cold and poor food.

Many older boys joined the Red Army to fight against fascism, just like their parents had in Spain. They wanted to repay the people who had helped them. Some Niños, like Dr. Juan Bote García, who was a teacher, faced difficulties for not wanting to teach only Soviet ideas.

About 130 Niños joined the Red Army and fought to defend major cities like Moscow, Leningrad, and Stalingrad. Some were even honored for their bravery. Seventy Spaniards died during the Siege of Leningrad, and 46 of them were children or teenagers.

Other Niños were moved to distant places like Samarkand and Kokand (in present-day Uzbekistan), Tbilisi (in present-day Georgia), or Krasnoarmeysk (in Russia). Some children faced very tough conditions and had to find ways to survive.

Even though the Niños were still under the care of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) and other Soviet groups, their leader, Jesús Hernández Tomás, often had to pressure authorities to provide basic necessities like food, medicine, and heating. Those who survived did so by living in harsh conditions, sometimes working in fields to earn a living.

By 1943, when Hernández left the Soviet Union, nearly 40% of the Niños had died. In 1947, an event was held to mark their arrival in Russia, but fewer than 2,000 children were present. There was criticism of the PCE for not sending the children back to Spain sooner. The experiences of the Niños reflected the widespread suffering of the Soviet population during World War II.

Efforts to Bring the Niños Home

The Spanish government under Francisco Franco wanted to bring the Niños, especially those in the Soviet Union, back to Spain. Even before World War II ended, the Falange, a political group, took charge of this effort. They worried that the Niños were being trained as communist activists.

The Falange's foreign service worked to get the children back. Records show that if a request for a child's return was denied, they would use "extraordinary means" to try and get the child back anyway. The government was always suspicious that returning Niños might be communist agents. They worried about the children's education in the Soviet Union.

When a child was brought back, they were often not returned to their families right away. Instead, they were placed with Auxilio Social, a government-supported aid organization, because the government wanted to ensure their education met their standards.

After the War: New Homes and Returns

After World War II, most of the surviving Niños returned to the areas in the Soviet Union where they had first settled. Many ended up living in Moscow, though some settled elsewhere. Eventually, those who had spent twenty years in the Soviet Union were allowed to visit Spain for holidays.

In 1946, a small group of about 150 Niños received permission to go to Mexico to reunite with their relatives there.

After Joseph Stalin's death in 1953, relations between Spain and the Soviet Union slowly improved. Spain joined the United Nations in 1955. In 1957, an agreement was made for the Niños who wished to return to Spain. The Soviet ship Crimea arrived in Castellón de la Plana with 412 Spaniards on board. Between 1957 and 1958, almost half of the Niños who had been sent to the Soviet Union came back to Spain.

However, the returning Niños sometimes faced difficulties. Some authorities in Spain mistrusted them, thinking they might have communist beliefs. For many families, the reunion was hard. Parents had sent away children for safety, but now they were meeting adults, some with their own children, after nearly twenty years. Their life experiences were very different. A significant number of Niños eventually decided to return to the Soviet Union.

Another group of about 200 Niños moved to Cuba between 1961 and the mid-1970s. They were sent as Soviet specialists by the Communist Party of Spain because they knew Spanish. They worked as translators, teachers, in construction, and even for Cuban intelligence. In Cuba, they were nicknamed "Hispano-Soviets."

Since the 1960s, some individuals have chosen to return to Spain. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Soviet Union, many more came back. Those who stayed permanently in the Soviet Union, especially in Moscow, often met at places like the Spanish Center.

Spain and the Soviet Union did not fully restore diplomatic relations until 1977. After the Soviet Union began to crumble in the late 1980s, the Niños faced legal uncertainty. In 1990, Spanish courts made it possible for them to get their Spanish nationality back. In 1994, the Niños were given the right to receive pensions from Spain. In 2005, those still living abroad and those who had returned after spending most of their lives outside Spain were also recognized for economic benefits.

In December 2003, the surviving Niños received the "Emigration Medal of Honour," a special award from Spain.

Notable Niños

- Araceli Sánchez Urquijo, the first woman to work as a civil engineer in Spain.

- Ángel Gutierrez, a theater director and actor, who founded the Chekhov Chambre Theatre in Madrid.

- Carmen Orive-Abad, the mother of the famous Soviet hockey player Valeri Kharlamov.

- Agustín Gómez, a footballer and captain of Torpedo Moscow.

See also

In Spanish: Niños de Rusia para niños

In Spanish: Niños de Rusia para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |