North Pacific right whale facts for kids

Quick facts for kids North Pacific right whale |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

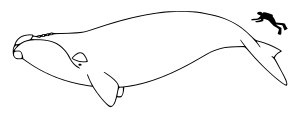

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Balaenidae |

| Genus: | Eubalaena |

| Species: |

E. japonica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Eubalaena japonica (Lacépède, 1818)

|

|

|

|

| Range map | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica) is a very large, strong baleen whale. These whales are extremely rare and in danger of disappearing forever.

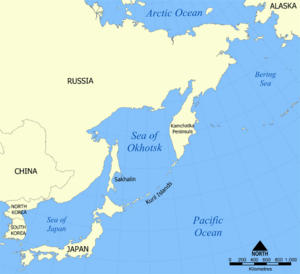

The population in the eastern North Pacific, which spends summers in the southeastern Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, might have fewer than 40 whales left. Another group in the west, found near the Commander Islands, Kamchatka Peninsula, Kuril Islands, and in the Sea of Okhotsk, is thought to have only a few hundred. Before large-scale whaling began around 1835, there were likely over 20,000 right whales in this area. Hunting right whales has been against international rules since 1935. However, between 1962 and 1968, illegal Soviet whaling killed at least 529 right whales in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, and at least 132 in the Sea of Okhotsk.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists this species as "Endangered." They say the Northeast Pacific population is "Critically Endangered," meaning it's in extreme danger. Some groups even call the North Pacific right whale the most endangered whale on Earth.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Since 2000, scientists have agreed that right whales in the North Pacific are a separate species, called Eubalaena japonica. Before this, they were thought to be the same as right whales in the North Atlantic and Southern Hemisphere. All these whales look very similar. The differences are found in their DNA.

The North Pacific, North Atlantic, and Southern right whales all belong to the same family, called Balaenidae. The bowhead whale, found in the Arctic, is also in this family.

Scientists use a special diagram called a cladogram to show how different animals are related. It's like a family tree that shows how species have evolved over time. Here's how the North Pacific right whale fits into its family:

| Family Balaenidae | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

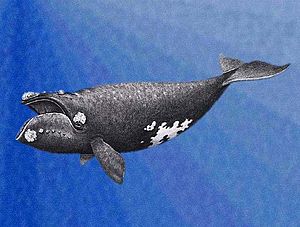

Appearance

The North Pacific right whale is a very large, strong baleen whale. It looks a lot like the North Atlantic and Southern right whales. In fact, they look so much alike that you can only tell them apart by looking at their genes. The North Pacific right whale might be a bit bigger than the other right whale species. Like other baleen whales, females are larger than males.

You can easily tell a North Pacific right whale from other whales in the North Pacific. They don't have a dorsal fin (the fin on their back). They have a wide, black back and rough patches on their head and lips called callosities. Their jawline is very curved, and their snout is narrow. They often have a V-shaped blow (the spray from their blowholes).

Adult North Pacific right whales can grow to be about 15 to 18.3 meters (50 to 60 feet) long. This is even larger than the North Atlantic right whale. They typically weigh between 50,000 and 80,000 kilograms (110,000 to 176,000 pounds). Some have been recorded weighing up to 100,000 kilograms (220,000 pounds)! They are much bigger and stouter than gray whales or humpback whales.

Right whales are special because of their callosities. These are rough, raised patches of skin on their heads. They are covered with thousands of small, light-colored creatures called cyamids, also known as whale lice. The callosities are found behind the blowholes and along the snout. The large one at the tip of the snout is called the "bonnet." Scientists are still not sure what the purpose of these callosities is.

The closely related bowhead whale does not have callosities. It has a more arched jaw and longer baleen plates. These two species do not live in the same areas during the same seasons. Bowhead whales prefer colder Arctic waters, while right whales stay further south.

Most of what we know about the North Pacific right whale's body comes from whales caught by whalers in the 1950s and 1960s.

What They Eat and How They Behave

Feeding

North Pacific right whales mostly eat tiny creatures called copepods. They especially like a species called Calanus marshallae. They have also been seen eating other types of copepods and small shrimp larvae.

Unlike whales that lunge to catch prey, right whales are "skimmers." They swim with their huge mouths open, letting water flow in. The water then flows out through their long, fine baleen plates, which act like a sieve. The baleen traps the tiny copepods inside. Right whales need millions of these tiny copepods to get enough energy. So, they must find areas where copepods are very concentrated, with more than 3,000 per cubic meter of water.

Behavior

Scientists have not had many chances to watch North Pacific right whales. Whaling in the 1800s happened before scientists were very interested in whale behavior. By the time they became interested, there were very few whales left. Early observations suggested that the more whales were hunted, the more aggressive and harder to approach they became. Recent sightings also show that these whales are very sensitive to ships. They often swim away or stay underwater longer to avoid them.

In 2006, a whale-watching boat off the Kii Peninsula, Japan, saw a right whale jump out of the water six times in a row. In 2011, the same operator had a very close encounter with a curious and playful right whale. It swam around the boat for over two hours, breaching, spyhopping (poking its head out of the water), and slapping its tail and fins. The boat had to leave because the whale kept following them! Another playful whale was seen near the Bonin Islands in 2014.

Like other right whales, North Pacific right whales are known to interact with other whale species. They have been seen with humpback whales. In 1998, two gray whales were seen chasing a right whale off California. In 2012, a young right whale was seen swimming with a group of critically endangered Western gray whales in Sakhalin's Piltun Bay.

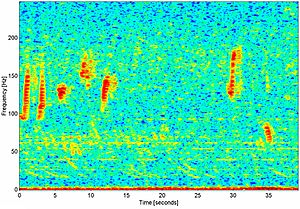

Sounds They Make

Right whales in other oceans make many different sounds. North Pacific right whales are harder to study because there are so few of them and they live in remote areas. Most of the sounds recorded for them have been in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska.

It seems that North Pacific right whales make calls similar to other right whale species. These are low-frequency sounds that seem to be for talking to each other. Scientists don't think right whales use sound to find things, like dolphins do.

Between 2000 and 2006, NOAA scientists used listening devices in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska. They recorded over 3,600 North Pacific right whale calls. Most of these calls came from shallow waters in the southeastern Bering Sea, which is now a protected area for them. About 80% of the calls were "up-calls," which sound like a short, rising whistle. These calls were often heard at night.

The "up-calls" of right whales are unique enough that scientists can use them to tell if right whales are in an area. However, humpback whales also make complex calls, and some parts can sound similar to right whale calls. So, humans often need to check the recordings carefully to be sure.

Right whales in other oceans also make a loud, sudden sound called a "gunshot call." For a long time, scientists weren't sure if North Pacific right whales made this sound. But in 2017, new research confirmed that they do. These gunshot calls are heard much more often than up-calls and are less likely to be confused with humpback whale sounds. This helps scientists find right whales more easily using listening devices.

How Many Are Left?

Past Population

Before whaling ships arrived in the North Pacific around 1835, there were probably 20,000 to 30,000 North Pacific right whales. The population near Japan might have been smaller due to older net whaling.

There was very little hunting of right whales by Native Americans along the west coast of North America. So, 1835 is a good year to think of as the starting point for their population size.

Scientists didn't count the whales in the 1800s. The only way to estimate their past numbers is by looking at how many were caught by whalers. In just one decade, from 1840 to 1849, between 21,000 and 30,000 right whales were killed in the North Pacific. To support this many catches, the population must have been at least 20,000 to 30,000 whales. This is similar to the number of Gray whales in the North Pacific today.

On the western side, in Japan, people had been hunting right whales from shore using nets for centuries. These hunts were very damaging to the whale populations.

Current Population

Today, the North Pacific right whale population is estimated to be about 30–35 whales in the eastern North Pacific. In the western part of their range, there are about 300+ whales. Even if you combine these numbers, it's the smallest known population of any whale species. It's probably only 2% of what it was in 1835. Because of this, the species is listed as Endangered. The eastern population is considered Extremely Endangered.

Scientists believe there are two main groups of these whales, one in the east and one in the west. They are managed as separate groups because we don't know much about how much they mix.

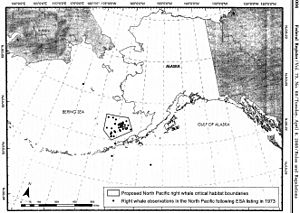

Bering Sea and Northeast Pacific

Most recent sightings and sound recordings of right whales in the eastern North Pacific have been in a small area of the southeastern Bering Sea. Many of these are within or near the protected "Critical Habitat" for this species. A smaller number of sightings have been in the Gulf of Alaska and off the coasts of British Columbia.

A 2015 study suggested there are only about 30 whales left in the eastern group, mostly males. This number is based on genetic studies and photo identification. Scientists found no new information that would increase this estimate.

Sea of Okhotsk and Western North Pacific

The 2015 study found more right whales in the western North Pacific than in the east. However, even this population is still one of the smallest marine mammal populations in the world.

In the west, most recent sightings are around the Kamchatka Peninsula, Kuril Islands, Sea of Okhotsk, and Commander Islands, and off Japan. This area includes Russian and Japanese waters, making surveys difficult.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Japanese scientists estimated about 900 right whales in the Sea of Okhotsk. However, other scientists believe this estimate was too high, and the actual number was likely much smaller, perhaps around 400. After a 14-year gap, Japanese researchers surveyed the area again in 2005 and saw similar numbers of whales.

More recently, surveys off Hokkaido (Japan) and the Kuril Islands from 1994 to 2013 found 55 sightings of right whales, including ten mother-calf pairs.

Where They Live

Past Distribution

Before 1840, North Pacific right whales lived in a very large area. They could be found from the Sea of Okhotsk in the west all the way to the coast of Canada.

We know about their past locations mostly from the logbooks of whaling ships. In the 1840s, a U.S. Navy captain named Matthew Fontaine Maury collected information from over 2,000 whaling logbooks. He created "Whale Charts" that showed where whales were most common. These charts showed that right whales were concentrated along both coasts of Kamchatka and in the Gulf of Alaska.

Another researcher, Charles Townsend, also mapped whale catches from logbooks in 1935. His maps showed three main areas where right whales were caught: the Gulf of Alaska, Kamchatka and the Sea of Okhotsk, and the Sea of Japan.

Scientists have used these old records to try and figure out if there was just one large group of right whales in the North Pacific, or if there were separate groups. They now believe there were at least two groups, one in the west and one in the east. It's still unclear if the Sea of Okhotsk population was a separate group.

Right whales usually live in warmer waters than bowhead whales. However, there are some records of them being in the same areas in the northeastern Sea of Okhotsk. In summer, right whales can be found in the southeastern Bering Sea. Bowhead whales migrate further north into the Arctic. In winter, bowhead whales move south into the Bering Sea, but right whales migrate even further south, away from the ice.

Modern Distribution

Summer Areas

Despite many searches by planes and ships, and listening devices, only a few small areas in the eastern North Pacific report recent sightings. Most are in the southeastern Bering Sea, followed by the Gulf of Alaska.

In August 2015, NOAA Fisheries searched for North Pacific right whales in the Gulf of Alaska. They used both visual observers and listening devices. They heard calls from a single right whale but could not see it. This shows how hard it is to find these rare whales.

Listening devices show that right whales migrate into the southeast Bering Sea in late spring and stay until late fall. They are most active there from July to October.

Northwestern Pacific

There are very few reports of right whales in the western North Pacific. A small group of right whales still lives in the Sea of Okhotsk in the summer.

Right whales in the Sea of Okhotsk live in the southern part of the sea, around the Kuril Islands and east of Sakhalin Island. This area is remote and mostly in Russian waters, making it hard to study.

Recent sightings near the Kuril Islands and off the southern tip of the Kamchatka Peninsula suggest these might be important areas for the species today.

Threats to Their Survival

The United States government has a "Recovery Plan" for the North Pacific right whale. This plan looks at the different dangers facing these whales.

Very Small Population

When animal populations become very small, they face special risks.

- Inbreeding: There are so few whales that they might start breeding with close relatives. This can lead to health problems.

- Vulnerability to Bad Events: A very small population is easily wiped out by things like a lack of food for a few years. The amount of copepods (their food) in the Bering Sea can change a lot due to weather and ocean conditions.

- Finding Mates: With so few whales spread across a huge ocean, it's hard for them to find each other to mate. Right whales usually travel alone or in small groups. Female whales call out to attract males, but increasing ship noise in the ocean makes it harder for their calls to be heard.

Oil and Gas Activities

Oil and gas exploration and production in the whale's habitat can be very dangerous. This includes oil spills, pollution, ships hitting whales, and noise. Oil fields off the Sakhalin Islands in the Sea of Okhotsk are in the habitat of the western right whale population.

Oil exploration involves loud seismic testing (sound blasts) to map the ocean floor. These loud noises can disturb whales. Scientists are still learning how much ship noise and industrial activities affect right whales' communication, behavior, and where they live.

Environmental Changes

The North Pacific right whale's home is changing, which threatens its survival. Two big concerns are global warming and pollution.

Right whales need high amounts of copepods to eat. Global warming can affect how many copepods there are and how they gather in groups.

Hybridization with Bowhead Whales

As the Arctic Ocean warms, different species are starting to meet in new areas. In 2009, a cross between a bowhead whale and a North Pacific right whale was seen in the Bering Sea. Scientists worry that if the very rare North Pacific right whales breed with the more common bowhead whales, it could lead to the North Pacific right whale disappearing. The hybrid offspring might be healthy at first, but over time, this could weaken the pure right whale population.

Entanglement in Fishing Gear

Getting tangled in fishing gear is a major threat to right whales. This can kill them quickly or cause long-term stress that makes them sick and less able to reproduce.

Commercial fishing happens year-round in the areas where North Pacific right whales live. Most modern entanglement records involve Japanese fisheries.

Here are some examples of entanglements:

- February 2015: A young right whale got tangled in mussel farm ropes in Korea but was released.

- October 2016: A 9.5-meter whale was killed after getting tangled in Volcano Bay, Hokkaido, Japan.

- June 2013: One of two right whales seen off British Columbia had serious injuries from fishing gear.

- 2011: A young right whale was killed after getting tangled in a net in Ōita Prefecture, Japan. Its meat was later sold.

- August 3, 2003: Two right whales were seen in the Sea of Okhotsk. One had a large scar from fishing gear.

- December 25, 1996: A right whale was found alive but tangled in a crab net in the Sea of Okhotsk. It was released but still had some net attached.

- September 1, 1995: A whale was found dead from entanglement in the Sea of Okhotsk.

- August 1992: A whale was found alive with fishing gear wrapped around its tail in the Sea of Okhotsk.

- 1994: A whale died from entanglement in a Japanese drift net.

Ship Collisions

Collisions with large ships are the biggest threat to North Atlantic right whales. While North Pacific right whales don't usually live in busy shipping lanes, this threat still exists.

Ship Noise

Increased noise from ships and oil exploration can make it harder for right whales to hear each other. It might also make them more likely to be hit by ships. Scientists are still studying how much ship noise affects North Pacific right whales.

Predation

There is no clear evidence of killer whales attacking North Pacific right whales. However, killer whales are known to attack bowhead whales in the Arctic. If killer whales do attack, it would likely affect young whales more.

Whaling

Historic whaling is the main reason North Pacific right whales are so endangered today. The two worst periods were 1839–1849 (when American ships hunted them) and 1963–1968 (when Soviet whalers illegally killed them). The illegal Soviet whaling in the 1960s killed hundreds of right whales.

While whaling was a huge threat in the past, there are no records of whalers targeting this species since the 1980s. So, this threat is small now.

Lack of Funding

Studying and protecting whale populations that are spread out and hard to find is very expensive. Governments are facing budget cuts, making it harder to get money for this work. For example, most research on right whales in the Bering Sea was funded by oil and gas exploration projects. When those projects were put on hold, the funding stopped. The U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service says there is "no funding at all for North Pacific right whale research" right now.

In Japan, information about free-swimming right whales is limited. Many sightings by local people are not officially reported.

How We Can Help Them

Finding Right Whales

A big challenge in protecting these whales is finding them. Unlike other right whale species, there are no reliable places where researchers can always find North Pacific right whales. In the eastern part of their range, there are so few that it's like "looking for a needle in a haystack." In the western part, it's hard to get access to Russian waters, and fog often makes it impossible to see.

Scientists are now using new technology to listen for right whales. They use special listening devices that can detect whale calls underwater. These devices can find whales even when it's foggy or rough, or when the whales are submerged.

Scientists use two types of listening devices:

- Sonobuoys: These are floating devices dropped from ships that listen for short periods.

- Moored acoustic recorders: These are devices placed on the ocean floor that record sounds for months.

Often, scientists use both methods. They first detect whales with sound, then try to find them visually with ships. In 2004, NOAA scientists used listening devices to find right whale calls in the Bering Sea. This helped them find the whales visually, take photos, collect genetic samples, and attach tags.

Researchers have also developed satellite tags that can be attached to whales. These tags can send information about the whale's location and movements for months. However, it's very hard to attach these tags to North Pacific right whales because they are so rare and hard to find.

International Laws

After World War I, countries became worried about whale populations shrinking. In 1931, the first international whaling treaty was signed, banning the hunting of all right whales. However, Japan and the Soviet Union did not sign it at first.

In 1946, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) was created. Since then, the IWC has banned commercial hunting of right whales. The IWC now classifies E. japonica as a "Protection Stock," meaning no commercial whaling is allowed.

However, the IWC rules allow countries to issue permits to kill whales for "scientific research." Between 1955 and 1958, the Soviet Union and Japan issued permits to kill 23 North Pacific right whales for science. This provided much of the information we have about their bodies and reproduction. No more scientific permits have been issued for these whales.

In the 1960s, the Soviet Union illegally killed thousands of protected whales, including right whales, around the world. They then lied in their reports to the IWC. This illegal whaling was a secret for 40 years until the Soviet government collapsed. In 2006, a former Soviet biologist revealed that hundreds of right whales were killed illegally in the North Pacific between 1963 and 1968. Later, more documents showed the total illegal catch was even higher, around 765 right whales. These catches mostly targeted large, mature whales, which greatly hurt the population's ability to recover.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) bans all international trade of right whale parts or products. The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) also lists the North Pacific right whale as endangered. Countries that signed this convention must protect these animals and their habitats.

United States Laws

In the United States, three main laws protect the North Pacific right whale:

- Whaling Convention Act of 1949: This law makes the IWC's whaling bans, including the ban on right whales, part of U.S. law.

- Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 (MMPA): This law gives the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) the power to manage all whale species. NOAA classified the North Pacific right whale as "depleted" in 1973, which gives it special protections.

- Endangered Species Act (ESA): NOAA has listed the North Pacific right whale as "endangered" under this law. The ESA provides even more protection than the MMPA.

Critical Habitat

The Endangered Species Act requires NOAA to mark certain ocean areas as "Critical Habitat." This means special protective measures must be taken in these areas.

In 2006, NOAA designated two critical habitats for E. japonica: one in the Gulf of Alaska and one in the southeastern Bering Sea. These areas are important because they have the high concentrations of copepods that right whales need to eat. Once an area is named critical habitat, federal agencies must make sure their actions don't harm it.

Recovery Plan

In 2013, NOAA released a "Recovery Plan for the North Pacific Right Whale." This plan describes what scientists know about the species and the threats it faces. It also suggests ways to help them recover, mostly through more research, like listening for whales and studying old whaling records.

Canadian Regulation

Canada also has laws to protect right whales. In 2003, Fisheries and Oceans Canada created a plan to help E. japonica in Pacific Canadian waters. They also analyzed critical habitat for right whales and other large whales in British Columbia.

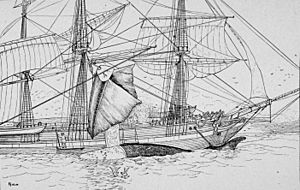

History of Whaling

Whaling Before 1835

In Japan, hunting right whales dates back to at least the 1500s. In 1675, a new method was invented: catching whales in nets before harpooning them. A hunting group could have 30–35 boats and about 400 crew members. They hunted right whales, gray whales, and humpback whales.

Japanese whaling happened in two main regions: the south coast and the Sea of Japan. Catches were relatively small, for example, less than one right whale per year in some areas.

A few Native American tribes also hunted whales in the North Pacific, but their catches were much smaller than the Japanese. The Aleuts hunted right whales using poisoned harpoons, but their catch was likely only a few per year.

Early American and European whaling ships mostly stayed in the Atlantic and South Pacific. By the 1820s, whalers started using Hawaii as a base for hunting sperm whales.

Pelagic Whaling: 1835–1850

In 1835, a French whaling ship was the first to catch a North Pacific right whale north of 50°N. News spread quickly, and the number of whaling ships in the area grew from 2 in 1839 to 292 in 1846. About 90% of these ships were American.

The focus on right whales ended after 1848 when whalers discovered many unhunted bowhead whales in the Bering Straits. Bowheads were more common, easier to catch, and had more valuable baleen. So, whalers quickly switched to hunting bowheads, and the pressure on right whales decreased.

Between 1839 and 1909, an estimated 26,500–37,000 right whales were caught in the North Pacific. Most of these (80%) were caught in just one decade, from 1840 to 1849.

Industrial Whaling: 1850–1930s

After 1850, the number of right whales caught dropped sharply. By the end of the 1800s, whalers caught fewer than 10 right whales per year.

In the late 1800s, new technologies like steam-powered ships and explosive harpoons allowed whalers to hunt faster species like blue and fin whales. Small coastal whaling stations also opened, and they occasionally caught right whales.

After Official Protection

Later, "factory ships" processed whales at sea. Right whales continued to be caught, though rarely. Japan continued whaling until World War II. After the war, Japan joined the IWC, which banned right whale hunting. Except for the 13 whales caught for "scientific permits," Japanese whalers have followed this rule.

However, it's possible that several hundred whales were caught by Japanese whalers until the late 1970s, many of them unreported. In 1977, a right whale was killed after being driven into a port in Japan. A museum was later built to display its skeleton.

In the 1970s, Chinese and Korean whalers also caught four right whales. The last confirmed catch of a right whale in China was in 1977. The last claimed catch records of the species were two catches by Japanese whalers in the Yellow Sea in 1994.

Illegal Soviet Whaling: 1962–1968

In the 1960s, Soviet whalers were under pressure to meet production goals. Even though right whales were protected, they secretly hunted them. They killed every right whale they could find in the North Pacific and other oceans. The Soviet government then filed false reports, claiming they only killed one right whale by accident.

These illegal actions were a state secret for 40 years. Russian biologists who were on the whaling ships were often not allowed to examine the whale bodies. But some kept their own secret records. After the Soviet government fell, the new Russian government released some of this true data.

In 2006, a former Soviet biologist published records of 372 right whales caught by Soviet fleets in the Bering Sea and eastern North Pacific between 1963 and 1968. He also documented 126 killed in the Sea of Okhotsk and 10 in the Kuril Islands. Later, new documents showed the total illegal catch was even larger, reaching 765 right whales. These catches mostly involved large, mature whales, which severely damaged the population's ability to recover.

It was also revealed that Japan knew about these illegal hunts and did not report them. Japan and the Soviet Union had agreements to keep their illegal whaling activities secret.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ballena franca del Pacífico norte para niños

In Spanish: Ballena franca del Pacífico norte para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |