Numbat facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Numbat |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: |

Myrmecobiidae

|

| Genus: |

Myrmecobius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Myrmecobius fasciatus |

|

|

|

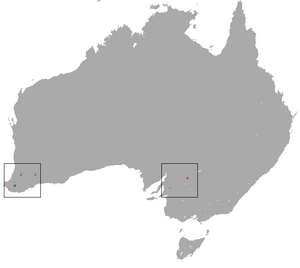

| Numbat range (green — native, pink — reintroduced) |

|

The numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) is a special type of marsupial that lives in the open woodlands of western Australia. People also call it the banded anteater because it loves to eat termites.

What makes the numbat unique is that it's one of the few marsupials active during the day. Most marsupials are nocturnal, meaning they are active at night. Numbat mothers don't have a pouch like kangaroos. Instead, they carry their four babies on their stomach. At night, numbats find shelter in hollow logs to sleep. In zoos, numbats can live for about 5 to 6 years.

These shy, long-tailed termite-eaters are in danger of extinction, which means very few are left in the wild. When Europeans first arrived in Australia, numbats lived across a huge area. They were found from the borders of New South Wales and Victoria all the way west to the Indian Ocean. They even lived as far north as the southwest part of the Northern Territory. Numbats were comfortable in many different habitats, including woodlands and dry, semi-arid areas.

Sadly, when the European red fox was brought to Australia in the 1800s, it caused a lot of harm. These foxes wiped out all the numbats in Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. They also nearly destroyed all the numbat populations in Western Australia. By the late 1970s, fewer than 1,000 numbats were left. They were only found in two small areas near Perth, called Dryandra and Perup. The numbat is now a special symbol, the emblem of Western Australia.

Contents

Understanding the Numbat's Family Tree

The numbat belongs to a unique family called Myrmecobiidae. It is the only living member of its family. This family is part of a larger group called Dasyuromorphia. This group includes many Australian marsupial carnivores, which are meat-eating animals.

Scientists have studied the numbat's DNA to learn about its past. They found that the ancestors of the numbat separated from other marsupials a very long time ago. This happened between 32 and 42 million years ago, during a period called the late Eocene. There used to be two types, or subspecies, of numbats. One was a rusty-colored type called Myrmecobius fasciatus rufus. Sadly, this subspecies has been extinct since at least the 1960s. So, only one type of numbat, M. fasciatus fasciatus, is alive today.

The name numbat comes from the Noongar language spoken by Indigenous people in southwest Australia. Another name for it is walpurti, from the Pitjantjatjara dialect. People also call it the banded anteater or marsupial anteater.

What Does a Numbat Look Like?

The numbat is a small and colorful animal. It measures between 35 and 45 cm long, including its tail. It has a pointy muzzle and a long, bushy tail that is about the same length as its body. Numbats can be different colors, from soft grey to reddish-brown. Many have a brick-red patch on their upper back. They always have a clear black stripe that runs from their nose, through their eyes, to their small, round ears.

On their back, numbats have between four and eleven white stripes. These stripes become lighter towards the middle of their back. Their belly is usually cream or light grey. The tail is covered with long, grey hair mixed with white. Numbats weigh between 280 and 700 grams.

Unlike most other marsupials, the numbat is active during the day. This is mainly because of its special diet. Numbats eat only termites. They have five toes on their front feet and four on their back feet. Like other animals that eat termites or ants, the numbat has small, weak teeth. It doesn't chew much because termites are soft.

The numbat has a long, narrow tongue covered in sticky saliva. This helps it catch termites. Its mouth also has special ridges that help scrape termites off its tongue so they can be swallowed. The numbat's digestive system is quite simple. This is because termites are easier to digest than ants, as they have softer outer shells. Numbats get a lot of water from their food, so their kidneys don't need special ways to save water like other animals in dry places. Numbats also have a special scent gland on their chest. They might use this to mark their territories.

Numbats use their excellent sense of smell to find termite mounds. But they also have the best eyesight of any marsupial. This is unusual for marsupials and helps them see predators during the day. Numbats can also go into a state of torpor, which is like a deep sleep. This can last up to 15 hours a day in winter.

Where Numbats Live and Their Homes

Numbats used to live all over southern Australia. Their range stretched from Western Australia to north-western New South Wales. But their living areas have shrunk a lot since Europeans arrived. Now, numbats only survive in two small areas in Western Australia. These are the Dryandra Woodland and the Perup Nature Reserve. Luckily, they have been successfully moved to a few protected areas. These include places in South Australia (Yookamurra Sanctuary) and New South Wales (Scotia Sanctuary).

Today, numbats are mostly found in eucalypt forests. But they once lived in many other places. These included dry woodlands, spinifex grasslands, and even sand dune areas.

How Numbats Live and Behave

Numbats are insectivores, meaning they eat insects. Their diet is almost entirely made up of termites. An adult numbat needs to eat up to 20,000 termites every day! Since they are the only marsupial fully active during the day, numbats spend most of their time looking for termites. They dig them out of the loose ground with their front claws. Then, they use their long, sticky tongue to catch them. Even though they are called "banded anteaters," they don't usually eat ants on purpose. Any ants found in their droppings are likely ones that were also eating termites, so the numbat ate them by accident.

Animals that hunt numbats include the carpet python, introduced red foxes, and various types of falcons, hawks, and eagles.

Adult numbats are solitary animals. This means they mostly live alone. Each male or female numbat sets up its own territory, which can be as large as 1.5 square kilometers (about 370 acres). They defend this area from other numbats of the same sex. Numbats usually stay within their territory. However, male and female territories can overlap. During breeding season, males might leave their usual area to find mates.

Numbats have strong claws for their size. But they aren't strong enough to break into the hard termite mounds. So, they have to wait until the termites are active and building tunnels. Numbats use their excellent sense of smell to find these shallow tunnels. Termites build these tunnels just below the ground surface, making them easy for the numbat to dig into.

The numbat's day is timed with when termites are most active. This depends on the temperature. In winter, numbats feed from mid-morning to mid-afternoon. In summer, they wake up earlier, rest during the hottest part of the day, and then feed again in the late afternoon.

At night, the numbat goes back to its nest. This can be inside a hollow log, a tree, or a burrow in the ground. A burrow is usually a narrow tunnel about 1 to 2 meters long. It ends in a round room lined with soft plant materials like grass, leaves, and shredded bark. The numbat can block the entrance to its nest with its thick rump. This helps to stop predators from getting in. Numbats don't make many sounds. But they have been heard to hiss, growl, or make a 'tut' sound when they are bothered.

Numbat Life Cycle and Reproduction

Numbats usually have babies in February and March, which is late summer in Australia. They typically have one litter of young each year. If they lose their first litter, they can sometimes have a second. The mother is pregnant for about 15 days. Then, she gives birth to four babies.

Unlike most other marsupials, female numbats do not have a pouch. Instead, their four teats are protected by a patch of thick, golden hair. The area around their belly and thighs also swells up when they are feeding their young.

The baby numbats are only about 2 cm long when they are born. They immediately crawl to the mother's teats and stay attached until late July or early August. By then, they have grown to about 7.5 cm. They start to grow fur when they are about 3 cm long. Their adult patterns begin to show when they reach 5.5 cm. After they stop drinking milk, the young are left in a nest or carried on the mother's back. They become fully independent by November. Female numbats can have their own babies the next summer. However, males don't become mature enough to breed until they are a year older.

Saving the Numbat: Conservation Efforts

Before Europeans settled in Australia, numbats lived across a huge area. This stretched from the borders of New South Wales and Victoria west to the Indian Ocean. They were also found as far north as the southwest corner of the Northern Territory. Numbats lived in many different woodland and semi-arid areas. However, the release of the European red fox in the 1800s caused a disaster. It wiped out all numbat populations in Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. It also nearly destroyed all numbats in Western Australia. By the late 1970s, fewer than 1,000 numbats were left. They were only found in two small areas near Perth, called Dryandra and Perup.

When the numbat was first discovered, people thought it was beautiful. Its appeal led to it being chosen as the animal symbol of Western Australia. This also started efforts to save it from extinction.

The two small numbat populations in Western Australia likely survived because these areas had many hollow logs. These logs provided safe places for numbats to hide from predators. Since numbats are active during the day, they are more vulnerable to predators than other marsupials their size. Their natural predators include the little eagle, brown goshawk, collared sparrowhawk, and carpet python. When the Western Australia government started a program to control foxes in Dryandra, numbat sightings increased by 40 times!

Since 1980, a big research and conservation program has helped increase the numbat population a lot. Numbats have also been successfully moved to areas where there are no foxes. Perth Zoo plays a big part in breeding numbats in captivity. These captive-bred numbats are then released into the wild. Even with this success, the numbat is still at high risk of extinction. It is currently classified as an endangered species.

Since 2006, volunteers from Project Numbat have been working to help save the numbat. One of their main goals is to raise money for conservation projects. They also raise awareness by giving presentations at schools, community groups, and events. Numbats can be successfully brought back to their old homes if they are protected from introduced predators.

Early Discoveries of the Numbat

Europeans first learned about the numbat in 1831. It was found by an exploration group led by Robert Dale in the Avon Valley. George Fletcher Moore, who was part of the group, wrote about finding it:

"Saw a beautiful animal; but, as it escaped into the hollow of a tree, could not ascertain whether it was a species of squirrel, weasel, or wild cat..."

The next day, he wrote:

"chased another little animal, such as had escaped from us yesterday, into a hollow tree, where we captured it; from the length of its tongue, and other circumstances, we conjecture that it is an ant-eater—its colour yellowish, barred with black and white streaks across the hinder part of the back; its length about twelve inches."

The first scientific description of the numbat was published by George Robert Waterhouse. He described the species in 1836 and its family in 1841. The numbat, Myrmecobius fasciatus, was also included in the first part of John Gould's book, The Mammals of Australia, which came out in 1845. It featured a drawing of the species by H. C. Richter.

Images for kids

-

A reproduction of George Fletcher Moore's drawing of a numbat

See also

In Spanish: Numbat para niños

In Spanish: Numbat para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |