Operation Mincemeat facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Mincemeat |

|

|---|---|

| Part of Operation Barclay | |

| Operational scope | Tactical deception |

| Location | Spain |

| Planned | 1943 |

| Planned by | |

| Target | Abwehr |

| Date | April 1943 |

| Executed by | |

| Outcome | Successful |

Operation Mincemeat was a clever plan by the British during World War II. Its goal was to trick the Germans about where the Allies would invade in 1943. This secret mission helped hide the real plan to invade Sicily, an island near Italy.

Two British intelligence officers found the body of a man named Glyndwr Michael. They dressed him as a Royal Marines officer named "Captain William Martin." They also put fake personal items on him, like letters and photos, to make him seem real. They even placed fake secret letters on the body. These letters suggested the Allies planned to invade Greece and Sardinia, making Sicily seem like a trick.

This operation was part of a bigger plan called Operation Barclay. It was inspired by an idea from 1939, called the Trout memo. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and General Dwight D. Eisenhower approved the plan. The body was taken by submarine to the coast of Spain. A Spanish fisherman found it the next morning.

The Spanish government, which was neutral, shared copies of the fake documents with the Abwehr, the German spy agency. Later, they returned the originals to the British. Experts checked the documents and found they had been read. Secret German messages, decoded by the British (called Ultra), showed that the Germans believed the trick. Because of this, Germany moved many soldiers to Greece and Sardinia. Sicily received no extra troops before or during the invasion.

We don't know the full impact of Operation Mincemeat. But Sicily was freed faster than expected, and fewer soldiers were lost. The story of Operation Mincemeat has been told in books and movies, including The Man Who Never Was (1956) and Operation Mincemeat (2021).

Contents

How the Plan Started

The Idea for Mincemeat

In 1939, soon after World War II began, Rear Admiral John Henry Godfrey wrote a paper called the Trout memo. It compared tricking an enemy to fly fishing. The historian Ben Macintyre says that Godfrey's assistant, Lieutenant Commander Ian Fleming, likely wrote most of it. Fleming later wrote the James Bond books.

The memo had many ideas to trick the Axis powers. One idea, called "A Suggestion (not a very nice one)," was to put fake papers on a dead body. The enemy would then find the body and the misleading papers.

Using fake documents to trick the enemy was not new. The British had used similar tricks, like the "Haversack Ruse," in both World Wars. For example, in 1942, a body with a fake map was placed in a minefield. The Germans used the map, and their tanks got stuck in soft sand.

In September 1942, a British plane crashed near Cádiz, Spain. Everyone on board died, including a courier carrying top-secret documents. His body washed ashore and was found by Spanish officials. The letter he carried was still on him and had not been opened. However, other intelligence showed that a French agent's notebook from the plane had been copied by the Germans. This showed British planners that some information found by the Spanish was being shared with the Germans.

British Spies and the Plan

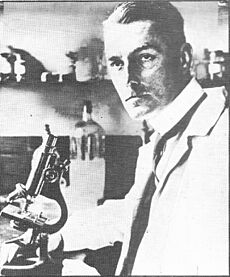

A month after the plane crash, British intelligence officer Charles Cholmondeley came up with his own version of the Trout memo idea. He called it "Trojan Horse," after the famous Greek story. His plan was to get a body from a London hospital. They would fill its lungs with water and put fake documents in a pocket. Then, they would drop the body from a plane into the sea. The enemy would think a plane had crashed and this was one of the passengers.

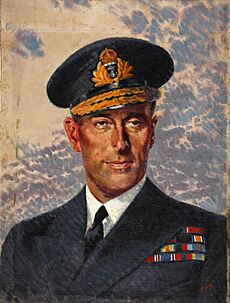

Cholmondeley worked for MI5, Britain's spy agency. His plan was first turned down in November 1942. But the committee thought the idea had potential. John Masterman, the committee chairman, asked Ewen Montagu to work with Cholmondeley. Montagu was a lawyer who worked for the Naval Intelligence Division. He was in charge of naval deception operations. He knew that deception was needed for the upcoming Allied invasion in the Mediterranean.

The War Situation

By late 1942, the Allies had won in North Africa. They then looked for the next place to attack. British leaders believed an invasion of France from Britain couldn't happen until 1944. Prime Minister Winston Churchill wanted to use the forces from North Africa to attack Europe's "soft underbelly."

There were two main options. The first was Sicily. Taking Sicily would open the Mediterranean Sea for Allied ships. It would also allow an invasion of Italy. The second option was to go into Greece and the Balkans. This would trap German forces between the Allies and the Soviets. At a meeting in January 1943, the Allies chose Sicily, calling the plan Operation Husky. They planned to invade by July.

Allied leaders worried that Sicily was too obvious a choice. Churchill reportedly said, "Everyone but a bloody fool would know that it's Sicily." They feared the Germans would notice the build-up of troops and supplies.

Adolf Hitler was worried about an invasion in the Balkans. This area provided raw materials for Germany's war industry. The Allies knew Hitler's fears. So, they launched Operation Barclay, a deception plan to make him think the Balkans were the target. This would draw German forces away from Sicily.

To make the eastern Mediterranean seem like the target, the Allies set up a fake headquarters in Cairo, Egypt. They pretended it was for a "Twelfth Army" with twelve divisions. They held military exercises in Syria, using fake tanks to fool observers. They also hired Greek interpreters and collected Greek maps and money. Fake radio messages about troop movements were sent from the fake headquarters. Meanwhile, the real command post for the Sicily invasion used landlines to reduce radio traffic.

Planning the Trick

Creating the Plan

Montagu chose the code name Mincemeat from a list of available names. On February 4, 1943, Montagu and Cholmondeley presented their plan to the Twenty Committee. It was a new version of Cholmondeley's Trojan Horse idea. The Mincemeat plan was to put documents on a body and float it off the coast of Spain. Spain was neutral but known to work with the German spy agency, the Abwehr. The committee approved the plan, and Montagu and Cholmondeley were told to continue preparing.

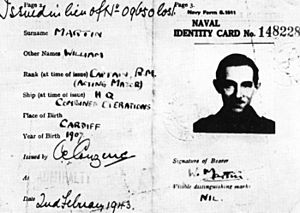

Montagu and Cholmondeley started to create a fake life story for the body. They chose the name "Captain (Acting Major) William Martin" of the Royal Marines. They picked "Martin" because many Royal Marines had that name. As a Royal Marine, Major Martin was under the Admiralty. This made it easy to send all official questions about his death to the Naval Intelligence Division. Also, Royal Marines wore standard uniforms that were easy to get. The rank of acting major was important enough for him to carry secret documents, but not so important that everyone would know him.

To make Martin seem like a real person, they added personal items to his pockets. This is called "pocket litter." These items included a photo of a fake fiancée named Pam. The photo was of an MI5 clerk, Jean Leslie. They also put two love letters from Pam in his pocket. There was a receipt for a diamond engagement ring. Other personal letters included one from Martin's fake father and a note from his bank asking for an overdue payment. To make sure the letters could still be read after being in seawater, MI5 scientists tested different inks.

Other items included a book of stamps, a silver cross, a St. Christopher's medallion, cigarettes, matches, a pencil, keys, and a receipt for a new shirt. To show Martin had been in London, they added ticket stubs from a London theatre and a bill for a hotel stay. All these items helped create a timeline of his activities in London from April 18 to 24.

Montagu and Cholmondeley found Captain Ronnie Reed of MI5, who looked like the body. Reed agreed to be photographed for the identity card in a Royal Marine uniform. The three identity cards and passes needed to look old, not brand new. So, Montagu rubbed them on his trousers to make them look used. Cholmondeley, who was about the same size, wore the uniform to make it look worn.

The Fake Documents

Montagu had three rules for the main document that would contain the fake invasion plans. First, it had to clearly mention the fake target. Second, it had to name Sicily and another place as a cover. Third, it had to be an unofficial letter, not something sent by a diplomat or in code.

The main document was a personal letter from Lieutenant General Sir Archibald Nye, a high-ranking officer, to General Sir Harold Alexander. Alexander was the commander of the Anglo-American forces in Algeria and Tunisia. After several tries, Nye wrote the letter himself. The letter mentioned several fake sensitive topics. The most important part said that:

We have recent information that the Boche [the Germans] have been reinforcing and strengthening their defences in Greece and Crete and C.I.G.S. [Chief of the Imperial General Staff] felt that our forces for the assault were insufficient. It was agreed by the Chiefs of Staff that the 5th Division should be reinforced by one Brigade Group for the assault on the beach south of CAPE ARAXOS and that a similar reinforcement should be made for the 56th Division at KALAMATA.

The letter also said that Sicily and the Dodecanese islands were "cover targets" for the attacks.

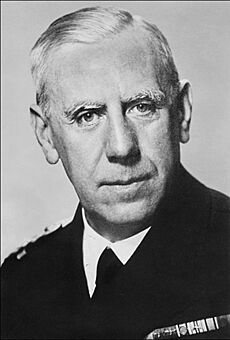

There was also a letter introducing Martin from his fake commanding officer, Vice-Admiral Louis Mountbatten. This letter was for Admiral of the Fleet Sir Andrew Cunningham, the Allied naval commander in the Mediterranean. Martin was described as an expert in amphibious warfare, on loan until "the assault is over." The letter included a clumsy joke about sardines. Montagu hoped the Germans would think this was a hint about invading Sardinia. A single black eyelash was placed inside the letter. This was a secret way to check if the Germans or Spanish had opened it.

They put the documents in an official briefcase that would be noticed. To explain why Major Martin had a briefcase, they gave him two copies of an official pamphlet on combined operations. They also included a letter from Mountbatten to Eisenhower, asking him to write a foreword for the pamphlet's US edition. Martin was given a leather-covered chain, like those used by couriers to secure their cases. The chain was looped around his trench coat belt.

Final Approval

Montagu and Cholmondeley carefully chose where to drop the body. They decided on Huelva on the coast of southern Spain. This was because the tides and currents there would likely carry the body to shore. Also, there was a very active German spy in Huelva, Adolf Clauss, who had good contacts with Spanish officials. The British vice-consul in Huelva, Francis Haselden, was also reliable.

They decided to use a submarine to deliver the body. Trying to fake a plane crash at sea with flares was too risky.

On April 13, 1943, the Chiefs of Staff committee approved the plan. They told Colonel John Bevan, who managed deception operations, to get final approval from Churchill. Two days later, Churchill approved the operation. He then asked Eisenhower, the overall military commander in the Mediterranean, for his final confirmation. Eisenhower's plan to invade Sicily would be affected. Bevan sent a secret telegram to Eisenhower, who confirmed on April 17.

Putting the Plan into Action

In the early hours of April 17, 1943, Glyndwr Michael's body was dressed as Major Martin. The fake personal items were placed on him, and the briefcase was attached. The container with the body was put into a van driven by an MI5 driver. Cholmondeley and Montagu rode in the back of the van. They drove all night to Greenock, Scotland. There, the container was loaded onto the submarine HMS Seraph. The submarine's commander, Lt. Bill Jewell, and his crew had experience with special operations.

On April 19, Seraph set sail. It arrived off the coast of Huelva on April 29. On April 30, they opened the container and carefully lowered the body into the water.

Spain's Role and German Reaction

The body of "Major Martin" was found around 9:30 AM on April 30, 1943, by a local fisherman. Spanish soldiers took it to Huelva and gave it to a naval judge. The British vice-consul, Haselden, was officially told about the body and briefcase. He sent secret messages back to London. The British knew these messages were being intercepted and decoded by the Germans. The messages made it seem very important for Haselden to get the briefcase back.

The Spanish released the body. "Major Martin" was buried with full military honors on May 2.

The Spanish navy kept the briefcase. Despite pressure from German spies, they did not give the briefcase or its contents to the Germans. On May 5, the briefcase was sent to naval headquarters near Cadiz, then to Madrid. While in San Fernando, German sympathizers secretly photographed the contents. The letters were not opened there.

Once the briefcase reached Madrid, a senior German spy, Karl-Erich Kühlenthal, became very interested. He asked Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, the head of the Abwehr, to personally ask the Spanish for the documents. The Spanish agreed. They carefully removed the still-damp papers by rolling them up and pulling them out of the sealed envelopes. The letters were dried and photographed. Then, they were soaked in salt water for 24 hours and put back into their envelopes. The eyelash that had been placed inside was gone. The Germans received the information on May 8. Kühlenthal thought it was so important that he personally took the documents to Germany.

On May 11, the briefcase, with the documents, was returned to Haselden. He sent it to London. Experts in London examined the documents. They noticed the eyelash was missing. Further tests showed the paper fibers were damaged from being folded more than once. This confirmed the letters had been taken out and read. To make sure the Germans didn't suspect anything, another secret message was sent to Haselden. It said the envelopes had been checked and were not opened. Haselden leaked this news to Spaniards who were friendly with the Germans.

Final proof that the Germans had received the information came on May 14. A German message was decoded by the British at Bletchley Park. The message, sent two days earlier, warned that the invasion would be in the Balkans, with a trick attack on the Dodecanese. A message was sent to Churchill, who was in the United States. It said, "Mincemeat swallowed rod, line and sinker by the right people and from the best information they look like acting on it."

Montagu continued the deception. He included Major Martin's name in the list of British casualties published in The Times on June 4. By chance, the names of two other officers who died when their plane was lost at sea were also published that day. This made Major Martin's story seem even more real.

German Response

On May 14, 1943, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz met Hitler. They discussed the war. Dönitz said that Hitler did not agree that Sicily was the most likely invasion point. Hitler believed the Mincemeat documents confirmed that the main attacks would be on Sardinia and Greece.

Hitler told Benito Mussolini, the Italian leader, that Greece, Sardinia, and Corsica must be defended "at all costs." He ordered the experienced 1st Panzer Division to move from France to Greece. This order was secretly heard by the British on May 21. By the end of June, German troops on Sardinia had doubled to 10,000. Fighter planes were also moved there. German torpedo boats moved from Sicily to the Greek islands. Seven German divisions moved to Greece, making a total of eight. Ten divisions were sent to the Balkans, making eighteen there.

On July 9, the Allies invaded Sicily in Operation Husky. German messages showed that even four hours after the invasion began, twenty-one aircraft left Sicily to reinforce Sardinia. For a long time after the invasion, Hitler still believed an attack on the Balkans was coming. In late July, he sent General Erwin Rommel to Greece to prepare its defense. By the time the German high command realized their mistake, it was too late to change anything.

What Happened Next

On July 25, 1943, as the battle for Sicily went badly for the Axis forces, Italian leaders voted to limit Mussolini's power. They gave control of the Italian armed forces to King Victor Emmanuel III. The next day, Mussolini was dismissed as prime minister and imprisoned. A new Italian government took power and began secret talks with the Allies. Sicily fell on August 17. About 65,000 Germans held off 400,000 American and British troops long enough for many Germans to escape to Italy.

Historians say that Sicily was captured easily not just because of Mincemeat. Other factors included Hitler's distrust of the Italians. He didn't want to risk German troops with Italian troops who might surrender. Historian Michael Howard called Mincemeat "perhaps the most successful single deception operation of the entire war." But he also said Hitler's focus on the Balkans had a big impact. Ben Macintyre writes that it's impossible to know the exact effect of Mincemeat. However, the British expected 10,000 casualties in the first week of fighting, but only a seventh of that number were lost. The navy expected 300 ships to be sunk, but only 12 were lost. The predicted 90-day campaign ended in 38 days.

Historian Smyth writes that because of the Sicily invasion, Hitler stopped the Kursk offensive on July 13. This was partly because of the Soviet army's performance. But it was also because Hitler still thought the Sicily landing was a trick before an invasion in the Balkans. He wanted troops ready to move quickly. Smyth notes that once Hitler gave up the advantage to the Soviets, he never got it back.

Operation Mincemeat's Legacy

Montagu received an award in 1944 for his role in Operation Mincemeat. Cholmondeley received an award in 1948 for leading the plan. Duff Cooper, a former government minister who knew about the operation, published a spy novel in 1950 called Operation Heartbreak. It featured a body with fake documents being floated off the coast of Spain to trick the Germans. The British security services decided the best response was to publish the true story of Mincemeat. Montagu quickly wrote The Man Who Never Was (1953), which sold two million copies. This book became the basis for a 1956 film. Montagu later published his wartime autobiography, Beyond Top Secret U (1977), which gave more details about Mincemeat. In 2010, journalist Ben Macintyre published Operation Mincemeat, a history of the events.

The story has also been featured in other media. A 1956 episode of The Goon Show was called "The Man Who Never Was." A play called Operation Mincemeat was first staged in 2001. It focused on Glyndwr Michael's homelessness. The story was also the basis for a 2014 musical, Dead in the Water. In 2015, a Welsh theatre company produced a musical called The Man Who Never Was, based on the operation and Michael's life. Another musical, Operation Mincemeat, started in 2019 and moved to a bigger theatre in 2023. In 2014, a BBC TV show, Fleming: The Man Who Would Be Bond, showed parts of Operation Mincemeat and Ian Fleming's connection to it. In 2022, the film Operation Mincemeat was released.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission took care of Major Martin's grave in Huelva in 1977. In 1997, they added the words "Glyndwr Michael served as Major William Martin RM" to his gravestone. In November 2021, a memorial was placed at the Hackney Mortuary in London.

|

See also

In Spanish: Operación Mincemeat para niños

In Spanish: Operación Mincemeat para niños

- Operation Copperhead

- Operation Bodyguard

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |