Otto von Guericke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Otto von Guericke

|

|

|---|---|

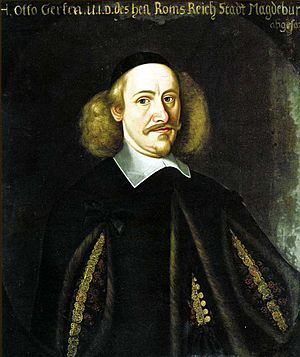

Otto von Guericke, engraving after a portrait by Anselm van Hulle (1601–1674)

|

|

| Born |

Otto Gericke

November 30, 1602 |

| Died | May 21, 1686 (aged 83) |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physicist, politician |

| Influences | Nicolaus Copernicus |

| Influenced | Robert Boyle |

Otto von Guericke (born November 30, 1602 – died May 21, 1686) was a German scientist, inventor, and politician. He made huge contributions to science during the Scientific Revolution. He was a pioneer in studying the vacuum, atmospheric pressure, and electrostatic forces. He also believed in "action at a distance" (like gravity) and "absolute space".

Von Guericke was a very religious man. He believed that the vacuum of space was part of God's creation. He described it as something that "contains all things" and is "more precious than gold."

Contents

About Otto von Guericke

Early life and education

Otto von Guericke was born in Magdeburg, Germany. His family was wealthy and well-known. He had private teachers until he was 15. In 1617, he started studying law and philosophy at Leipzig University.

His studies were interrupted in 1620 when his father died. He then continued his education at other universities, including Helmstedt, Jena, and Leiden. At Leiden, he first learned about mathematics, physics, and military engineering. He finished his education with a nine-month trip to France and England.

Family life

In 1626, Otto von Guericke returned to Magdeburg and married Margarethe Alemann. They had three children. Sadly, Margarethe died in 1645. In 1652, von Guericke married Dorotha Lentke.

Political career

Von Guericke came from an important family in Magdeburg. His father and grandfather had both been members of the city council and even served as mayor. In 1626, Otto von Guericke also joined the city council.

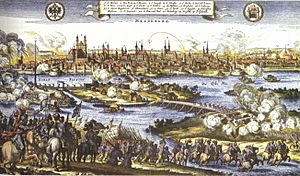

However, the Thirty Years' War had started in 1618. This long and terrible war soon reached Magdeburg. Luckily, von Guericke had left the city before it was surrounded by an army. In May 1631, the city was attacked in what is known as the Sack of Magdeburg. About 80% of its 25,000 people died, and most buildings were destroyed. Von Guericke lost all his belongings.

He returned to Magdeburg in 1631. Because of his engineering education, he was chosen to help rebuild the city. He became a master brewer to help the city and himself earn money.

In 1646, he was elected as Magdeburg's Burgomeister. This was the city's chief leader, similar to a mayor, and gave him a lot of power. He held this important job until he retired in 1678. During his 40 years in office, he went on many diplomatic trips. He met powerful leaders like dukes, kings, and emperors across Europe.

In 1666, Emperor Leopold I made Otto von Guericke a nobleman. This allowed him to add "von" to his name, changing it from "Gericke" to "Guericke."

Diplomatic missions

Otto von Guericke's first diplomatic trip was in 1642 to meet the Elector of Saxony. He wanted to get better treatment for Magdeburg from the Saxon military. In 1648, he represented Magdeburg at the peace talks that ended the Thirty Years' War.

During a trip in 1654, von Guericke showed off his air-pump invention. He used his scientific achievements to impress people and help his city's political goals. He would sometimes let people believe his inventions were magic, which helped him as a leader.

Early science experiments

Von Guericke was curious about the new ideas of space, especially the Copernican idea of vast, empty space. He wanted to create this "nothing" on Earth.

He first tried to create a vacuum by pumping water out of wooden barrels. But the wood was too porous, and air kept leaking in. In 1647, he decided to try pumping out air instead of water. This helped him solve the problem.

Science and politics meet

His science and political work came together in 1654. He was invited to show his vacuum experiments to important leaders at the Reichstag in Regensburg.

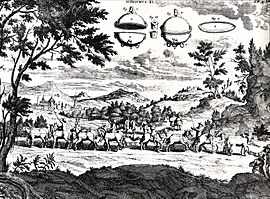

He built a vacuum pump and used it to remove air from two large, joined Magdeburg hemispheres. The air pressure outside held the halves together so strongly that 16 horses, eight on each side, could not pull them apart! He showed this amazing experiment again to the King of Prussia in 1663 and was given a lifetime pension.

One of the leaders, Archbishop Elector Johann Philipp von Schönborn, bought von Guericke's equipment. He sent it to a Jesuit college. A professor there, Fr. Gaspar Schott, started writing to von Guericke. This led to von Guericke's work being published for the first time in 1657, as an appendix to Fr. Schott's book.

This book caught the attention of Robert Boyle, another famous scientist. Boyle was inspired to do his own experiments on air pressure and the vacuum. He published his findings in 1660.

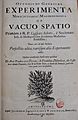

Von Guericke continued his scientific work while also handling his political duties. He wrote his main book, Ottonis de Guericke Experimenta Nova (ut vocantur) Magdeburgica de Vacuo Spatio, which means "Otto von Guericke's New (so-called) Magdeburg Experiments on Empty Space." This book, published in 1672, described his vacuum experiments in detail. It also included his groundbreaking experiments with electrostatics, where he showed electrostatic repulsion for the first time.

Later years

In 1677, von Guericke was finally allowed to retire from his city duties after many requests. In 1681, he moved to Hamburg with his second wife to avoid the plague in Magdeburg. Otto von Guericke died peacefully in Hamburg on May 21, 1686. His body was brought back to Magdeburg and buried there.

The Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg is named in his honor.

His Scientific Work

Air pressure and the vacuum

In 1650, von Guericke invented the vacuum pump. This pump used a piston and a cylinder to pull air out of containers. He used it to study the properties of a vacuum.

He showed the power of air pressure with dramatic experiments. His most famous experiment was with the Magdeburg hemispheres in 1657. He made two large, hollow copper hemispheres, about 20 inches across. He put them together and pumped out the air, creating a vacuum inside. The air pressure from the outside pushed the hemispheres together so tightly that 16 horses, pulling from opposite sides, could not separate them! It would have taken more than 4,000 pounds of force to pull them apart.

With his experiments, Guericke proved wrong the old idea of "horror vacui" (nature abhors a vacuum). For centuries, scientists believed that nature would always try to prevent a vacuum from forming. Guericke showed that substances were not "pulled" by a vacuum. Instead, they were "pushed" by the pressure of the air around them.

All of von Guericke's work on the vacuum and air pressure is described in his book, Experimenta Nova (1672). He also described how he crushed a non-spherical vessel by removing air from it. He showed that a flame would go out in a sealed container without air. He also demonstrated that air has weight and how fog can be made in a sealed vessel.

He also built a barometer to measure changes in air pressure, which helped him predict the weather. He even had a small statue that would move its finger to show if the air was heavy or light, indicating rain or storms. His barometer helped pave the way for meteorology, the study of weather.

Electrostatic investigations

Von Guericke also studied how objects could affect each other from a distance. He called these "potencies." For example, he thought the Earth had a "conservative potency" that kept its atmosphere and pulled objects back down.

He described his work on electrostatics in his book. Before 1663, he invented a simple frictional electrical machine. This was a sulfur globe attached to an iron rod. By rubbing the globe with a dry hand, he could create an electrical charge on its surface. This allowed him to attract and repel other light objects.

He noticed that when the sulfur globe was rubbed, it would not only attract light objects but sometimes push them away before attracting them again. He also showed that this electrical attraction could work through a linen thread, proving it didn't need air to happen. This "mysterious" attraction and repulsion was actually electrical conduction.

See also

In Spanish: Otto von Guericke para niños

In Spanish: Otto von Guericke para niños

- Air pump

- Cloud physics

- Thermoscope

Images for kids