Paranephrops facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Paranephrops |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Northern koura, P. planifrons | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Infraorder: |

Astacidea

|

| Family: |

Parastacidae

|

| Genus: |

Paranephrops

White, 1842

|

| Species | |

|

|

|

|

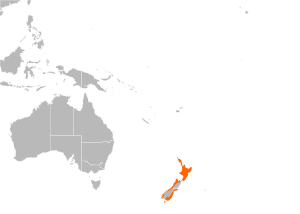

Paranephrops is a type of freshwater crayfish found only in New Zealand. People often call them freshwater crayfish or koura. Kōura is their name in the Māori language.

There are two main types of koura. The northern koura, Paranephrops planifrons, lives mostly in the North Island. You can also find it in Marlborough, Nelson, and the West Coast of the South Island. The southern koura, Paranephrops zealandicus, lives only in the eastern and southern parts of the South Island and on Stewart Island/Rakiura.

For a long time, koura have been a traditional food for Māori. Today, there's a small industry that farms koura. They supply these crayfish to restaurants.

Contents

What are Koura Like?

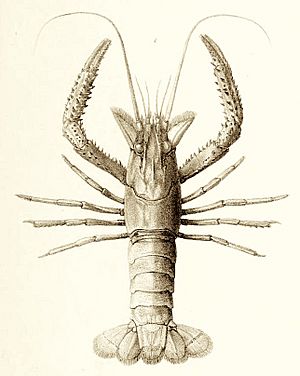

The northern koura (P. planifrons) can grow to about 70 mm long. The southern koura (P. zealandicus) is a bit bigger, reaching about 80 mm. Southern koura also have shorter antennae.

Koura have a strong first pair of legs called chelipeds. These are like pincers. They use them to find food and to protect themselves from enemies or other koura. The pincers of P. zealandicus are much hairier than those of P. planifrons.

Koura use their four pairs of walking legs to move around. They have small pleopods (small leg-like parts under their tail), but they don't use them for swimming. If a koura feels scared, it can quickly flick its tail forward. This makes it shoot backward very fast.

You can tell if a koura is male or female by looking underneath it. Males have two small bumps at the base of their fourth pair of legs. Females have small holes at the base of their second pair of legs.

Koura's Life and Home

What Koura Eat

Koura in nature are scavengers. This means they eat many different kinds of food. Eating animal protein helps them grow the most. Their main food sources are small water creatures. These include snails, midges, and mayflies.

Young koura need more protein than adult koura. This is because they are growing faster. They mostly eat small water bugs. Koura living in lakes often feed close to the shore. This area, called the littoral zone, has the most food.

Koura might move to deeper, darker parts of lakes during the day. This helps them hide from predators. At night, they move back to the shallow areas to find food.

Where Koura Live

Koura live in many freshwater places. You can find them in lakes, streams, rivers, and swamps. They like to live in muddy or gravelly areas.

Koura are active at night. They move into shallower water when it's dark. During the day, they go to deeper water. They hide under rocks, trash like cans and bottles, and plants. In soft mud, they might dig burrows or fan-shaped holes. For example, in Lake Rotoiti, they dig at depths of 5 to 10 meters.

In streams, koura hide under fallen leaves, logs, and tree roots. They also use undercut banks for shelter. The roots of tree ferns that hang into the stream are great hiding spots for young koura.

Who Eats Koura and Other Dangers

Eels, perch, catfish, and trout are the main water animals that eat koura. Other animals that eat koura include rats, kingfishers, shags, scaup, stoats, and kiwi birds.

In the Rotorua lakes area, shags eat a lot of koura. Large trout also eat koura. Streams and lakes with many trout often have fewer koura.

Koura can sometimes eat each other, which is called cannibalism. This usually happens if a koura is sick or shedding its skin. Cannibalism is more common when many koura live close together. They compete for hiding spots and food. Young koura can be eaten whole by bigger koura. This is a challenge for koura farmers.

If a koura loses a pincer, it will use energy to grow it back. This means it might not grow as much overall.

There is one serious disease that affects koura. It's called "white tail disease." A tiny parasite causes it. This parasite damages the muscles in the koura's tail. The tail turns pale white, and the koura usually dies soon after.

How Koura Grow

Like all crustaceans, koura grow by shedding their outer shell, called an exoskeleton. When they are ready to shed, their shell becomes soft. They take calcium from the old shell, and then they shed it. A new, soft shell forms underneath. It takes several days for this new shell to get hard.

Koura have special stones called gastroliths in their stomach lining. These stones provide about 10–20% of the calcium needed for the new shell. The gastroliths drop into the koura's stomach and break down. This allows the koura to absorb the calcium.

After shedding, koura need a lot of calcium to harden their new shell. They often eat their old, discarded shell to get some of this calcium. They also absorb calcium from the water around them. Koura need at least 5 mg of calcium per liter of water to harden their shells.

Water temperature and calcium levels are very important for how fast koura grow. P. zealandicus can survive well (over 80% survival) in water below 16°C. If the temperature goes higher, more koura might die. Higher temperatures make koura more active. This can lead to more cannibalism. It can also make the water quality worse because they produce more waste.

Koura also survive better in water with higher calcium levels. This is because fewer koura die during shedding. It also makes them less likely to be eaten by predators. For koura farms, a calcium level of 20–30 mg per liter is best for growth and survival.

Koura Life Cycle and Reproduction

Female koura carry 20 to 200 eggs under the side flaps of their abdomen. The eggs take 3 to 4 months to hatch. During this time, male koura produce sperm.

Once the eggs hatch, the baby koura cling to their mother's abdomen. They use their tiny pincers to hold on. They stay there until they are about 4 to 10 mm long. By this size, they look like small adult koura. They have already shed their skin twice.

In Lake Rotoiti in New Zealand, koura mostly breed between April and July (autumn to winter). They also have a second breeding time from October to January (spring to summer). It takes about 28 weeks for eggs to hatch and juveniles to be released in autumn-winter. In spring-summer, it takes 19–20 weeks. Warmer temperatures make the eggs develop faster.

In streams, P. planifrons eggs take about 25–26 weeks to develop. For P. zealandicus in Otago streams, it can take up to 60 weeks.

Farming Koura (Aquaculture)

Only a few companies in New Zealand currently farm koura. Sweet Koura Enterprises Ltd and New Zealand Clearwater Crayfish Ltd are two examples. Koura are sold to fancy restaurants. They are often eaten as a starter dish.

Koura are ready to be harvested when they are longer than 100 mm. For P. planifrons, this can take 2 to 5 years.

Sweet Koura Enterprises Ltd is in Central Otago. They farm P. zealandicus in artificial ponds about 200 square meters in size. These ponds try to copy the natural places where P. zealandicus lives. Water for the ponds comes from underground and is given extra air. The water temperature is controlled to match the seasons. The best temperature for growth in these ponds is 15–18°C. P. zealandicus does not like fast temperature changes.

A pond's natural life can support 3–4 koura per square meter. Farmers also give koura extra food, like fish-based pellets. This food is made to have less protein and more calcium, which koura need. If too many koura are in one pond, more of them might die. This is because of more cannibalism and fighting for hiding spots and food.

New Zealand Clearwater Crayfish Ltd farms the northern koura, P. planifrons. They use a system where water flows by gravity through ponds and channels. A key step for this farm is to clean the koura. They put koura in clean running water without food for up to 2 days. This cleans out their insides. It makes the tail meat look white and appealing to people who eat it.

To breed koura on a farm, it's best to have one male for every five females during mating times. Once the babies hatch, they are moved to separate tanks based on their age. Creating artificial hiding places in the ponds can help koura survive. Plastic containers, old tires, plastic pipes, and bottles can all be used as homes for koura in ponds. The suggested depth for ponds used to farm P. zealandicus is 1.3 to 5.0 meters.

Koura farmers face some challenges. Water supplied to the ponds can get dirty from other activities, like livestock farming. This can affect koura survival. Predators like carp, eels, and birds can also get into the ponds. Farmers can use nets over the ponds to stop birds. Algal blooms can make the water have no oxygen. Also, too many koura in a pond can lead to cannibalism.

The future for koura farming in New Zealand looks good. There might be more demand from restaurants and tourists. However, selling koura to other countries might be harder. This is because of competition from other farmed freshwater crayfish. For example, the red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) is very popular. The United States and China eat huge amounts of it every year.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |