Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen

Erzstift Bremen

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1180–1648 | |||||||||||||

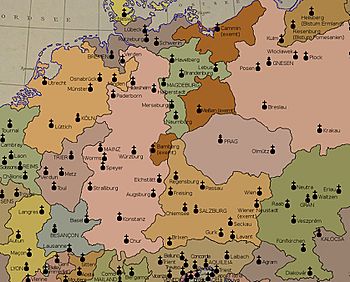

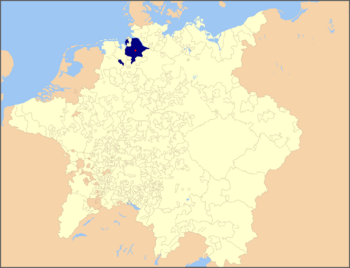

Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen within the Holy Roman Empire (as of 1648), the episcopal residence (in Vörde) shown by a red spot.

|

|||||||||||||

| Status | Defunct | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Bremen (seat of chapter) Vörde (seat of govt from 1219) Basdahl (venue of Diets) |

||||||||||||

| Common languages | Northern Low Saxon, Frisian | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Catholic Church | ||||||||||||

| Government | Principality | ||||||||||||

| Ruler: Prince-archbishop, administrator, or chapter (in vacancy) |

|||||||||||||

|

• 1180–1184

|

Prince-Archbishop Siegfried | ||||||||||||

|

• 1185–1190

|

Prince-Archbishop Hartwig II | ||||||||||||

|

• 1596–1634

|

Admin. John Frederick | ||||||||||||

| High Bailiff (Landdrost) | |||||||||||||

| Legislature | Estates of the Realm (Stiftsstände) convening at Diets (Tohopesaten or Landtage) in Basdahl | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||

|

• Break-up of stem

duchy of Saxony |

1180 | ||||||||||||

|

• Bremen city de facto

independent |

1186, especially from the 1360s | ||||||||||||

Summer 1627 |

|||||||||||||

10 May 1632 |

|||||||||||||

|

• Seized by Sweden

|

13 August 1645 | ||||||||||||

15 May 1648 |

|||||||||||||

| Currency | Reichsthaler, Bremen mark | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

The Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen (German: Fürsterzbistum Bremen) was a special kind of state in the Holy Roman Empire. It was ruled by an archbishop who had both religious and political power. This state existed from 1180 until 1648. After 1648, it became the Duchy of Bremen.

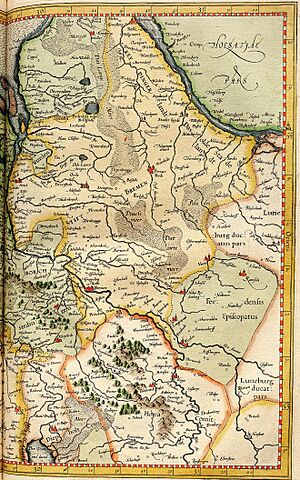

It's important not to confuse the Prince-Archbishopric with the modern Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Hamburg, which was founded much later in 1994. Also, the city of Bremen itself was mostly independent from the Prince-Archbishopric, especially after 1186. Most of the Prince-Archbishopric's land was north of the city of Bremen, between the Weser and Elbe rivers.

Contents

- A Look Back: History of Bremen

- Important People from Bremen's Church History

- Monasteries in the Prince-Archbishopric

- Images for kids

- See also

A Look Back: History of Bremen

Many old documents about the history of the Hamburg-Bremen church have been changed or faked over time. This makes it hard to know the exact early history of the area.

How Bremen's Church Started

The church in Bremen began around 787 AD. This was when a missionary named Willehad was working in the area. The church was set up by Charlemagne, a powerful emperor. Its job was to cover the Saxon lands around the Weser River and parts of Frisia.

Willehad made Bremen his main base. After the Saxons were brought under control in 804 or 805, Willehad's student, Willerich, became the first bishop of Bremen. At first, Bremen might have been under the control of the archbishops of Cologne.

Later, around 845, the Bremen church joined with the Archdiocese of Hamburg. This new combined church was meant to lead missionary work in the Nordic countries. New churches in the North were supposed to be under its control.

However, the area faced attacks from Normans and Wends. Also, Cologne kept trying to claim control over Bremen. In the late 800s, Pope Sergius III officially combined the two churches into the Archdiocese of Hamburg and Bremen. This stopped Cologne's claims.

After Hamburg was destroyed in 983, a new church council (called a chapter) was formed. This chapter included members from Bremen and other towns.

Where the Bremen Church Ruled

The Hamburg-Bremen church covered a large area. Today, this includes parts of the German states of Bremen, Hamburg, Lower Saxony, and Schleswig-Holstein.

The church had its best and worst times under Archbishop Adalbert of Hamburg (1043–1072). He tried to make Hamburg-Bremen a very important church center, but he failed. After his time, the name "Hamburg" was often dropped from the church's name.

In 1104, a church in Lund, Denmark, became an archdiocese. This meant it took over control of all the Nordic churches that used to be under Bremen. So, Bremen lost a lot of its influence in the North.

Bremen's remaining churches were in areas that had been destroyed by the Wends. These were Oldenburg-Lübeck, Ratzeburg, and Schwerin. When the Duchy of Saxony was broken up in 1180, these bishops gained more power. They became "prince-bishops," meaning they ruled their own territories like princes. The Archbishopric of Riga in Livonia was also under Bremen for some years (1186–1255).

Becoming a Prince-Archbishopric

In 1180, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa defeated Duke Henry the Lion. The Emperor then divided Saxony into many smaller territories. Each of these territories became directly controlled by the Emperor, not by a duke.

One of these new territories was the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen. This meant the Archbishop of Bremen now had political power over a specific area, acting like a prince. This new state was much smaller than the old Duchy of Saxony.

In 1186, Emperor Frederick I also gave the city of Bremen special rights. He said the city could be governed by its citizens and the Emperor, with the Prince-Archbishop having less say. The city of Bremen saw this as a sign that it was a Free imperial city, independent from the Prince-Archbishop.

Over time, the rulers of the Prince-Archbishopric and the city of Bremen often disagreed about the city's independent status. The city usually took part in the Prince-Archbishopric's meetings (called Diets) and paid taxes. Because the city paid a lot of taxes, its agreement was important. The city did not want the Prince-Archbishop to rule within its walls without its permission.

In 1219, the Bremen church council elected Gebhard of Lippe as archbishop. He made an agreement with the Hamburg chapter, confirming that three of its members could vote in archbishop elections.

The city of Bremen had its own guards and did not let the Prince-Archbishop's soldiers enter. There was a very narrow gate, called the Bishop's Needle, which only clergy could use. It was too narrow for knights to pass through. Because of this, the Prince-Archbishops preferred to live outside the city, first in Bücken and later in Vörde Castle (in Bremervörde), which became their main home in 1219.

The main church (Bremen Cathedral) and its offices were in a special area within the city called the Cathedral Liberty. Here, the city council did not interfere. Hamburg also had a similar Cathedral Immunity District.

The key, a symbol of Saint Simon Peter, became the symbol for the city of Bremen and the Prince-Archbishopric. You can see two crossed silver keys on a red background in the Prince-Archbishopric's coat of arms.

The Prince-Archbishopric's territory included several smaller areas. The archbishops or the church council gained power in these areas in different ways, like buying land or using force. However, they rarely had complete control. Power was often shared with local nobles, other church leaders, free farmers, or towns. Each area was called by a different name, depending on how much power the archbishop had there.

Today, the former Prince-Archbishopric's land includes parts of the Lower Saxon counties of Cuxhaven, Osterholz, Rotenburg upon Wümme, and Stade. It also includes the city of Bremerhaven. From 1145 to 1526, it also included the county of Ditmarsh in Schleswig-Holstein. The city of Bremen was legally part of the bishopric until 1646, but its citizens ruled it. The Prince-Archbishop moved his residence to Vörde in 1313.

How the Prince-Archbishopric Was Governed

Inside the Prince-Archbishopric, the archbishop and the church council had to work with other powerful groups. These groups slowly formed the Bishopric's Estates. This was a group that advised the rulers and made decisions about taxes. The Estates included nobles, knights, other clergy, free farmers, and townspeople.

The way the Estates, the Prince-Archbishop, and the church council worked together became the unofficial rules of the Prince-Archbishopric. However, these rules were not always clear. Archbishops often tried to reduce the power of the Estates, while the Estates fought to make their power official. The church council sometimes sided with the archbishop and sometimes with the Estates, depending on what helped them most. Everyone used tricks, threats, and even violence to get their way.

Between 1542 and 1549, the church council and the Estates managed to remove Prince-Archbishop Christopher, who spent too much money and acted like a dictator. The council often chose very old candidates for archbishop, so they wouldn't rule for long. They also sometimes chose young people, hoping to control them. Sometimes, they delayed elections for years, ruling the Prince-Archbishopric themselves during that time.

Outside the Prince-Archbishopric, it was an "imperial estate." This meant its rulers were directly under the Holy Roman Emperor and had no other authority above them. This gave them important rights and a degree of independence in their territory.

As a religious leader, the archbishop was the head of all Roman Catholic clergy in his archdiocese. This included the bishops of Oldenburg-Lübeck, Ratzeburg, and Schwerin.

The Prince-Archbishopric Loses Power

The Prince-Archbishopric often faced military threats from its neighbors. Since it didn't have a ruling family (a dynasty), its archbishops came from different backgrounds. This made the Prince-Archbishopric easily influenced by stronger powers. It also struggled to create a stable government that could unite its different groups.

The next two centuries saw many disagreements within the Church and the state. This prepared the way for the Protestant Reformation. The Reformation spread quickly, partly because the last Roman Catholic prince-archbishop, Christopher, was always fighting with the church council and the Estates. He also ruled the Prince-Bishopric of Verden at the same time and preferred to live there.

By the time Christopher died in 1558, most of the Prince-Archbishopric had become Protestant. Only a few monasteries remained Catholic. Many cities, like Bremen and Stade, had already closed their monasteries and used the buildings for schools, hospitals, or homes for the elderly.

Protestant Rulers of the Prince-Archbishopric

Under the Holy Roman Empire's rules, an emperor could only give a prince-bishop power if the Pope approved the election. If the Pope didn't approve, the emperor could give a temporary right to rule, but the ruler would be called an "Administrator" and couldn't vote in the Imperial Diet.

As the people of the Prince-Archbishopric became Lutheran or Calvinist, many members of the church council also became Protestant. So, they started electing Protestant candidates for archbishop. These Protestant rulers were often called "Administrators" because the Pope didn't approve them.

Many powerful families wanted their members to become the ruler of Bremen. The church council often took its time electing a new prince-archbishop. During this time, the council ruled the Prince-Archbishopric with the Estates.

In 1567, the council elected Duke Henry III of Saxe-Lauenburg as prince-archbishop. In return, his father gave up claims to certain lands. Henry agreed to respect the Estates' rights and the existing laws. Since he was young, the council and Estates ruled until he was older. He became the ruler in 1568.

Henry III was raised Lutheran but educated Catholic. At this time, the split between Catholics and Protestants wasn't as clear as it is now. The Pope still hoped the Reformation was temporary. Henry also became ruler of other prince-bishoprics, but the Pope never officially approved him. In 1575, Henry III married.

In 1580, Henry introduced a Lutheran church system for the Prince-Archbishopric. This meant he no longer performed the duties of a Roman Catholic bishop. In 1584, the Pope created the "Nordic Missions" to provide Catholic care in areas where the old archdioceses, like Bremen, had become Protestant.

Henry III died in 1585. After his death, Duke Adolf of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp influenced the Bremen council to elect his son, John Adolphus. John Adolf promised to respect the council's rights and try to get papal approval or imperial permission to rule. From 1585 to 1589, the council and Estates ruled for the young John Adolf.

Bremen During the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648)

At the start of the Thirty Years' War, the Prince-Archbishopric tried to stay neutral. However, King Christian IV of Denmark wanted to gain control of several prince-bishoprics, including Bremen.

In 1621, Christian IV arranged for his son Frederick to become the future ruler (coadjutor) of Bremen. This usually meant he would inherit the position. A similar deal was made for the Prince-Bishopric of Verden.

In 1619, Christian IV stationed Danish troops in the city of Stade, which was part of Bremen. In 1620, another Protestant leader asked Bremen to join the Protestant Union in the war. But the Administrator and the Estates of Bremen declared their loyalty to the Emperor and their neutrality.

With Danish troops in the area, Administrator John Frederick tried hard to keep Bremen out of the war. The city of Bremen also refused to join the war but began to strengthen its defenses.

By 1623, the war was getting closer. The territories in the region decided to raise an army to stay neutral. The war caused prices to rise, and people suffered from having to house and feed soldiers.

In 1625, Christian IV of Denmark was chosen as the commander of the local troops. He joined an alliance against the Habsburgs. The Catholic League's general, Tilly, warned John Frederick to stop hosting Danish troops. John Frederick again declared loyalty to the Emperor, but it was no use.

Christian IV ordered his troops to take control of important towns in Bremen. He was defeated by Tilly's troops in the Battle of Lutter in 1626. Christian IV and his remaining soldiers fled to the Prince-Archbishopric. John Frederick fled to another area, leaving the rule of Bremen to the church council and the Estates.

In 1626, Tilly's troops occupied the Prince-Bishopric of Verden. He demanded to enter Bremen. The Bremen council delayed, saying they needed to consult with the Estates. Meanwhile, Christian IV brought in Dutch, English, and French troops and forced Bremen to pay high war contributions.

By 1627, Christian IV had effectively removed John Frederick from power in Bremen. Christian IV then left to fight elsewhere. Tilly invaded Bremen and captured its southern parts. The city of Bremen closed its gates and relied on its strong defenses. In 1628, Tilly besieged Stade. After the Danish and English soldiers left, the entire Prince-Archbishopric was in Tilly's hands. Tilly then turned to the city of Bremen, which paid him money to avoid a siege. The city remained free.

Christian IV signed a peace treaty in 1629, ending Denmark's part in the war. He gave up his son Frederick's claims to Bremen and other prince-bishoprics.

The Emperor, Ferdinand II, used the "Edict of Restitution" in 1629 to try and bring Catholic rule back to Bremen. The few remaining Catholic monasteries became centers for this effort. Protestant nuns were forced out of their convents, and their property was given to Jesuits to help with the Catholic mission.

Ferdinand II wanted the Bremen council to remove the Protestant coadjutor Frederick. The council refused. So, Ferdinand II himself removed Frederick and appointed his own Catholic son, Leopold Wilhelm, as administrator.

The city of Bremen refused to give back church properties within its walls. It argued that it had been Protestant for a long time. The city even threatened to leave the Holy Roman Empire and join the independent Netherlands if forced. The city was too strong to be conquered.

In the occupied parts of Bremen, Catholic rule was restored. In Stade, churches were given to Catholic clergy, but the citizens did not attend Catholic services. Tilly expelled most Lutheran clergy. He also demanded high war payments from Stade. In 1630, Tilly left to fight the Swedes, who had just entered the war.

In 1631, John Frederick allied with Sweden, hoping to regain Bremen. He accepted the Swedish king's command. His newly recruited army, with Swedish help, reconquered Bremen and Verden. Catholic clergy fled. John Frederick was back in power, but Sweden now had control. The Prince-Archbishopric continued to suffer from housing and feeding soldiers.

After John Frederick died in 1634, the church council and Estates considered Frederick (the Danish Crown Prince) as the rightful successor. They had to convince the Swedes to accept him. In 1635, Frederick became the Lutheran Administrator of Bremen and Verden. But he had to show respect to the young Queen Christina of Sweden.

The Pope appointed Leopold Wilhelm as the Catholic Archbishop of Bremen in 1635, but he never gained real power because of the Swedish occupation.

In 1635/1636, the Estates and Frederick II agreed to neutrality with Sweden. But this didn't last. In the Danish-Swedish Torstenson War (1643–45), the Swedes took control of both prince-bishoprics. Christian IV of Denmark had to sign a peace treaty in 1645, giving up several territories, including Bremen and Verden, to Sweden. Frederick II had to resign as Administrator.

With Bremen again without a ruler, the new Pope appointed Francis of Wartenberg as a temporary head in 1645. But Wartenberg never gained power due to the Swedish occupation.

As the Treaty of Westphalia was being negotiated, which would give Bremen to Sweden, the city of Bremen sought official confirmation of its independent status from the Emperor. In 1646, Emperor Ferdinand III granted this to the city.

After 1648: The End of the Prince-Archbishopric

After 1648, the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen became the Duchy of Bremen and Principality of Verden, ruled by Sweden. For more information, you can read about the Duchy of Bremen and Principality of Verden (1648–1823) and the Stade Region (1823–1978).

Changes to the Roman Catholic Church in Bremen

In 1824, the old Bremen church territory was divided among other Catholic dioceses like Osnabrück, Münster, and Hildesheim. Hildesheim now covers most of the former Prince-Archbishopric.

The Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, which was mostly Calvinist, remained under the care of the "Vicariate Apostolic of the Nordic Missions." Bremen finally became part of the Diocese of Osnabrück in 1929.

Important People from Bremen's Church History

Here are some interesting people who lived or worked in the Archdiocese or Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen:

- Adam of Bremen (before 1050 - c. 1081): A Catholic church official and historian.

- Albert of Bexhövede (c. 1165–1229): A Catholic Bishop of Riga, who founded the city of Riga in 1201.

- Albert of Stade (c. 1187 - after 1265): An abbot (head of a monastery) and a writer of history.

- Emma of Lesum (c. 975-980 – 1038): A generous supporter of the Catholic Church and a Catholic saint.

- Christoph von Issendorff (1529–1586): A Lutheran noble and official in the Prince-Archbishopric.

- Henry of Zutphen (1488–1524): An Augustinian monk who became a Protestant reformer in Bremen.

Monasteries in the Prince-Archbishopric

- Altkloster Convent: A Benedictine nunnery (1197–1648).

- Bremen: Dominican St. Catherine's Friary (1225–1528).

- Bremen: Franciscan St. John's Friary (1225–1528).

- Bremen: Benedictine St. Paul's Friary (1050–1523).

- Harsefeld: Benedictine Archabbey of monks (1104–1648).

- Himmelpforten: Cistercian Porta Coeli Nunnery (before 1255–1647).

- Lilienthal: Cistercian St. Mary's Nunnery (1232–1646).

- Neuenwalde: Benedictine Convent of the Holy Cross (since 1219, until 1648).

- Neukloster: Benedictine New Nunnery (1270s–1647).

- Osterholz: Benedictine Nunnery in the Osterholz (1182–1650).

- Stade: Benedictine Our Lady's Friary (1141–1648).

- Zeven: Benedictine Zeven Nunnery (before 986–1650).

Images for kids

See also

- Duchy of Bremen

- Stade Region

- Elbe-Weser Triangle

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |