Richard Mohun facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard D Mohun

|

|

|---|---|

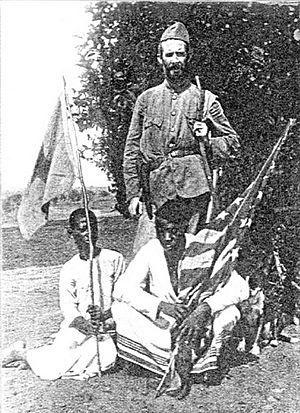

Mohun in the Congo c.1895. Seated at right is Sergeant Omari bo Hamise.

|

|

| Born | April 12, 1864 |

| Died | July 13, 1915 (aged 51) |

| Occupation | Explorer and soldier of fortune |

Richard Dorsey Loraine Mohun (born April 12, 1864 – died July 13, 1915) was an American explorer, diplomat, and mineral prospector. He worked for the United States government in Angola and the Congo Free State. Mohun also helped the Belgian army in a fight to remove Arab slave traders from the Congo.

Later, Mohun became the US consul in Zanzibar. He helped settle a conflict called the Anglo-Zanzibar War. After this, he went back to the Congo to search for valuable minerals.

One of his biggest projects was a three-year trip starting in 1898. He helped lay a telegraph line from Lake Tanganyika to Stanley Falls. He also worked with the Belgian authorities to improve conditions in the Congo.

Contents

Early Life and Adventures

Richard Dorsey Mohun was born in Washington, D.C. on April 12, 1864. His family had a long history with Africa. His grandfather, William McKenny, had many photos from his time there. Richard saw these photos as a child.

Mohun became interested in stopping the African slave trade. This trade was still happening in Eastern and Southern Africa. He was the fourth person in his family to work against it.

In 1881, Mohun joined the United States Navy. He served on a ship in the Mediterranean Sea for four years. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1889. That same year, he left the Navy to join the United States Department of State.

Mohun and his brother, Louis, worked for the Nicaragua Canal Construction Company. This company wanted to build a canal to connect the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Richard worked as an auditor for the company. However, the project faced problems with tropical diseases. The Mohun brothers returned home by 1892.

US Agent in the Congo

In 1892, Mohun was appointed as the US commercial agent to the Congo Free State. This job meant he was also America's diplomatic representative there. His main task was to explore the Congo's business potential. He also worked to increase trade between the US and the Congo.

Mohun traveled to the Congo with his brother, Louis. The US office was in Boma, near the coast. But Mohun also worked from Léopoldville, further inland. He helped an American citizen start a rubber factory. Mohun spent a lot of his time exploring the country's interior. He visited places no white person had seen before. He also studied the quality of the land and the crops grown by local people.

Mohun often faced challenges with local tribes. Once, his mail was stolen. When a local chief refused to return it, Mohun fought back. He attacked and burned several villages. He even captured the chief's son to get his mail back. Another time, he burned a town to "teach them a lesson" after being attacked. Mohun wrote a diary about his experiences. He always wanted to look good in his diary. He believed he was helping the country.

He also saw a funeral where he was horrified by the local customs. He could not intervene because he was outnumbered. Mohun believed much of the violence was caused by Arab slave traders. These traders were fighting against the Belgian authorities in the Congo Arab War.

The Chaltin Expedition

In 1893, Mohun was put in charge of the artillery for a Belgian expedition. This group, led by Louis Napoléon Chaltin, was fighting against slave traders. Mohun joined the expedition by steamer. Before he arrived, the expedition had destroyed a large village. Mohun continued with the group. They faced an outbreak of smallpox.

On March 29, the expedition found a large group of Arab slave traders. They launched a surprise attack. Mohun's artillery helped them win the fight. Mohun's group then burned a deserted town called Riba Riba. The expedition faced more smallpox. Many men died.

The group continued by steamer to Stanley Falls. They attacked the slave traders' main base. About 75 slave traders were killed. Many slaves and soldiers were freed. The slave traders were defeated and driven out of the country. This effectively ended the war.

Mohun then marched 500 miles to Kasongo. This was once the home of a famous slave trader, Tippu Tip. Mohun's force joined with a larger Belgian army. They attacked the fortified town. The Belgian forces killed 3,000 of the slave traders' men. They also blew up their powder magazines and burned the town.

In March 1894, Mohun was given a new task. He was made second-in-command of an expedition. Their goal was to find a navigable water route between Lake Tanganyika and the upper Lualaba River. Mohun discovered where the Luabala and Lumbridgi rivers met. He also proved that a lake, marked on many maps, did not exist. The river was very wide in some places and very narrow in deep gorges in others.

The expedition leader, Dr. Sidney Langford Hinde, became very ill. Mohun took command on April 11. He successfully completed the mission. Mohun also helped Dr. Hinde get back to Kasongo safely.

In April 1894, Mohun's sergeant identified two men who had been involved in the death of Emin Pasha. Mohun questioned them. He sent them to trial after they confessed. Mohun was given responsibility for governing about five million local people. He worked to improve local markets.

Mohun continued his efforts to stop the slave trade. He also made several mapping trips and opened new trade markets. His work helped open the Congo to outsiders. A map of the Lomami River was made using his records.

Mohun remained a US commercial agent during this time. He did not take money from the Belgian government for his services. However, he did receive $5000 from a Belgian company. He often wore a uniform to keep his men disciplined.

In 1894, he was honored by the Royal Belgian Geographical Society. King Leopold I also made him a chevalier of the Royal Order of the Lion. Mohun also received awards from the United Kingdom and France. He said his main goal was to improve life for the people by bringing them under Belgian influence. He also claimed that stories of Belgian cruelty were false.

However, Mohun later changed his mind. He spoke with Roger Casement, a British diplomat. Mohun believed that the Arab slave traders had done some good. He felt that slavery still existed under the new system. He also noted that a town of 45,000 people was completely destroyed after a Free State army post was set up there.

Zanzibar

Mohun's frequent trips in the Congo meant he spent less time on his duties as a commercial agent. The US State Department was happy with his work. This might be because he didn't get paid by the Belgians. He also helped make the Congo more stable for business.

Mohun left the Congo and returned to the United States. He married Harriette Louise Barry from New York City. After a short break, Mohun was appointed as the US Consul to Zanzibar in May 1895. He held this position until November 1897. This appointment may have been a reward for his work in the Congo. Harriette went with Mohun to Zanzibar. Their first son, Reginald Dorsey Mohun, was born there in April 1896.

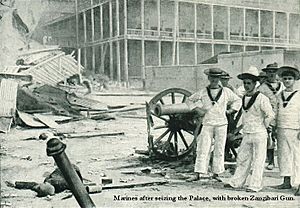

While in Zanzibar, Mohun became involved in the Anglo-Zanzibar War in August 1896. He acted as a go-between for the Sultan of Zanzibar and the British. He reported the war's outcome to the State Department. The new Sultan honored him for his help. Mohun also took many photographs during the war. He later published them. After the war, he continued to mediate between the Sultan and the British.

Mohun had a pet leopard cub named Dijini ("Devil"). He raised the leopard in his house. When he visited Europe, Dijini traveled with him. After scaring hotel staff in Antwerp, Mohun had to cage the leopard. He later gave Dijini to the Washington Zoo. When Mohun returned to Washington, he visited his former pet. He amazed zoo staff by putting his hand through the bars. The leopard licked his hand.

Telegraph Expedition

Mohun's job in Zanzibar ended in November 1897. He returned to Brussels, Belgium, with Harriette. The Belgian government was impressed by his work. In June 1898, they appointed him as a district commissioner. In July, King Leopold asked Mohun to lay a telegraph line. This line would go from Lake Tanganyika to Wadelai on the White Nile. Mohun accepted, even though he had called the area a "wretched country" just months before. He left Belgium for Africa in August 1898.

This telegraph line might have been part of a bigger plan. The idea was to build a line from the Cape of Good Hope to Cairo. Mohun was given a budget of three million francs. He chose his own team, including engineers and a doctor. He also had a military escort of one hundred men. Twenty of these men had worked with him before. They hoped to finish the work by 1900.

Mohun brought "100 boxes of trade goods" to trade with local people. These goods included bells, knives, mirrors, and music boxes. He also used American-made cloth to pay his escort. The expedition also had porters to carry equipment and lay the line. Mohun was also told to use his soldiers against rebels in the region.

The group traveled by ship to Tanganyika. Then they went to Fort Johnston at the southern tip of Lake Nyasa. They got more food there. They continued along the western bank of the lake to Karonga. The expedition probably used the Stevenson Road. This road connected Karonga to Zombe at Lake Tanganyika.

Mohun's group started laying the telegraph line at Albertville. They headed north along the lake's western bank. Then they entered the Congo Free State. They turned west to meet the River Congo at Kasongo. In July 1899, the group of ten European men was attacked by tribesmen. Mohun estimated there were 1,500 attackers. He claimed his group killed 300 and wounded 600 of them. His own group lost 9 men and had 47 wounded. Mohun used his Winchester rifle to help defend the group. They were later reinforced by more soldiers. The attackers fled.

Mohun's party followed the river north to Stanley Falls. After three years, the expedition finished the line. It was about 286 miles (460 km) long. This line allowed messages to be sent across central Africa for the first time. Mohun claimed that local people called him "Big master of the telephone." Mohun was the only white survivor of the expedition. He returned to Belgium from the west coast of the Congo. This meant he had traveled across the continent from east to west. Mohun claimed to be the first American to do this. This credit is usually given to Henry Morton Stanley. Mohun is seen as one of three Americans who helped open the Belgian Congo to outsiders. The others were Stanley and the missionary William Henry Sheppard.

Later Life and Work

Mohun's contract with the Belgian crown ended in October 1901. He returned to Harriette in Brussels. He became an advisor to King Leopold on managing the Congo. His second son, Cecil Peabody Mohun, was born in Brussels in March 1904.

Mohun did not want another long trip in Africa. He asked for a job at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in the US. He did not get a formal position. However, his idea might have led to the inclusion of the pygmy Ota Benga and other African tribesmen in the exhibition. He also tried to counter stories of Belgian abuses in the Congo.

In December 1905, King Leopold recommended Mohun to lead the Abir Congo Company. This company had been criticized for harsh treatment of workers. Mohun was appointed to make reforms. He had some success and also worked to get rid of the tsetse fly. In 1906, he suggested that Leopold II buy out Abir. This would put the company under direct control of the crown.

In 1907, Mohun was chosen by Thomas Fortune Ryan and Daniel Guggenheim. They were founders of the Forminière company. They wanted Mohun to lead a search for minerals in the Congo. This was called the Ryan-Guggenheim Expedition. It was funded by American money. It included a mineral prospecting team with Sydney Hobart Ball and Alfred Chester Beatty. They looked for new gold, copper, and coal deposits. The expedition also tried to capture a live Okapi. A wealthy person in Paris offered a $5,000 reward for one.

The expedition ended in 1909. They found valuable diamond deposits at Tshikapa. These were the first diamonds found in the country. They recommended the mineral-rich Kasai region for more exploration. The discovery of diamonds brought new income to the colony. Many American expeditions followed to find more diamonds.

Mohun's contract ended in November 1909. He briefly returned to his family in the USA. In 1910, he was hired by the Rubber Exploration Company. He inspected rubber areas in South Africa, Rhodesia, Mozambique, Madagascar, and Equatorial Africa. He also negotiated to buy them for the company. The rubber shipments were successful.

Later Life and Legacy

In August 1911, Mohun returned home to Royal Oak, Maryland. He needed to recover from injuries he received during his twenty years in Africa. He also spent time in the Virginia mountains.

In 1914, he served as paymaster for the American Red Cross. He was on a ship called SS Red Cross. It carried first aid supplies to Belgium to help those wounded during World War I.

Mohun died of a fever on July 13, 1915, at age 50. He had no prior signs of illness. His funeral was held at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle. He was buried in the family plot at Oak Hill Cemetery. During his time in Africa, he had only returned to the USA three times.

During his career, Mohun received honors from the British, French, and Belgian governments. He was a member of several Royal Geographical Societies. He spoke Arabic and Swahili fluently, in addition to English. A large collection of items and information Mohun gathered in Africa is now at the Smithsonian Museum. Many of his papers are held by the Belgian Royal Museum for Central Africa and the US National Archives and Records Administration. Harriette Mohun died on October 6, 1942. She was buried next to her husband.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |