Samson Raphael Hirsch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Samson Raphael Hirsch |

|

|---|---|

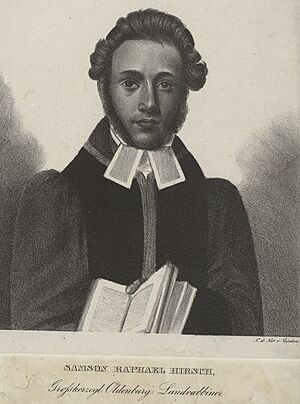

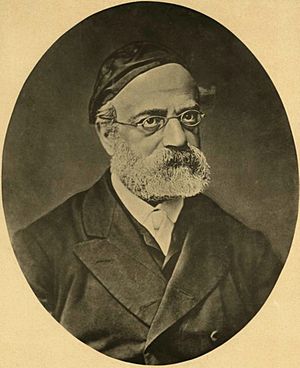

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch

|

|

| Religion | Judaism |

| Denomination | Orthodox Judaism |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | German |

| Born | June 20, 1808 (25 Sivan 5568) Hamburg, French Empire |

| Died | December 31, 1888 (27 Tevet 5649) Frankfurt am Main, German Empire |

| Spouse | Hannah Jüdel |

| Parents |

|

| Senior posting | |

| Title | Rabbi |

| Successor | Solomon Breuer |

| Position | Rabbi |

| Synagogue | Israelitische Religionsgesellschaft (IRG), Khal Adath Jeshurun |

| Buried | Frankfurt am Main |

| Semicha | Isaac Bernays |

Samson Raphael Hirsch ((Hebrew)) was a very important German Orthodox rabbi. He was born on June 20, 1808, and passed away on December 31, 1888. He is known as the founder of the Torah im Derech Eretz idea. This idea means that Jewish people should live by the Torah while also being involved in the modern world. His ideas greatly shaped Orthodox Judaism.

Rabbi Hirsch served as a rabbi in different cities like Oldenburg and Emden. Later, he became the chief rabbi of Moravia. From 1851 until his death, he led a special Orthodox community in Frankfurt am Main. He wrote many important books and published a monthly magazine called Jeschurun. In this magazine, he explained his Jewish philosophy. He strongly disagreed with Reform Judaism and early forms of Conservative Judaism.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Samson Raphael Hirsch was born in Hamburg. At that time, Hamburg was part of Napoleonic France. His father, Raphael Arye Hirsch, was a merchant but spent a lot of time studying the Torah. His grandfather, Mendel Frankfurter, started the Talmud Torah schools in Hamburg. His great-uncle, Löb Frankfurter, wrote several Hebrew books.

Hirsch was a student of Rabbi Isaac Bernays. His studies of the Bible and Talmud, along with his teacher's influence, made him want to become a rabbi. His parents had hoped he would be a merchant. To become a rabbi, he studied Talmud in Mannheim from 1828 to 1829. He received his semicha (rabbinical ordination) from Rabbi Bernays in 1830 when he was 22. After that, he went to the University of Bonn to study.

Rabbi Hirsch's Career

In Oldenburg

In 1830, Rabbi Hirsch became the chief rabbi of Oldenburg. During this time, he wrote his famous book, Neunzehn Briefe über Judenthum (Nineteen Letters on Judaism). This book was published in 1836 under the name "Ben Usiel." It made a big impact because it explained Orthodox Judaism in a clear and smart way. It also bravely defended all Jewish traditions and laws.

In 1838, Hirsch published Horeb, oder Versuche über Jissroel's Pflichten in der Zerstreuung. This book was a guide to Judaism for educated young Jewish people. He had actually written Horeb first. However, his publishers thought a book defending traditional Judaism would not sell well at a time when many people wanted reforms.

In Emden

Rabbi Hirsch stayed in Oldenburg until 1841. Then, he was chosen as the chief rabbi for the areas of Aurich and Osnabrück, living in Emden. For five years, he was very busy with community work. He did not have much time to write. However, he did start a secondary school there. This school taught both Jewish studies and regular subjects. This was the first time he put his idea of Torah im Derech Eretz into practice. This means combining Torah learning with worldly knowledge.

In 1843, Hirsch applied to be the Chief Rabbi of the British Empire. He was one of four finalists, but Nathan Marcus Adler got the position.

In Nikolsburg

In 1846, Rabbi Hirsch was called to be the rabbi of Nikolsburg in Moravia. In 1847, he became the chief rabbi of Moravia and Austrian Silesia. He spent five years helping to organize Jewish communities and teaching many students. As chief rabbi, he was also a member of the Moravian Landtag (parliament). There, he worked to get more civil rights for Jews in Moravia.

In Moravia, Hirsch faced challenges. Some people who wanted reforms criticized him. Also, some very traditional Orthodox Jews found his ideas too new. Rabbi Hirsch believed in a deeper study of the entire Hebrew Bible, not just the Torah and certain readings. This was different from what most religious Jews were used to at the time.

In Frankfurt am Main

In 1851, Rabbi Hirsch became the rabbi for an Orthodox group in Frankfurt am Main. Most of the Jewish community in Frankfurt had accepted Reform Judaism. This Orthodox group was called the "Israelite Religious Society" (IRG). Under Rabbi Hirsch's leadership, this group grew into a large community with about 500 families. Rabbi Hirsch remained their rabbi for the rest of his life.

He started the Realschule and the Bürgerschule in Frankfurt. These schools offered strong Jewish education along with secular subjects. He made sure that the secular studies fit with the values of the Torah (Torah im Derech Eretz). He also started and edited the monthly magazine Jeschurun (from 1855 to 1870, and again from 1882). He wrote most of the articles in this magazine himself.

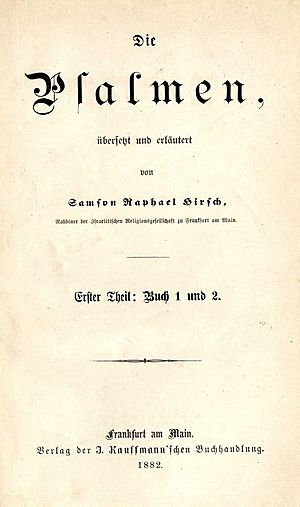

During this time, he wrote his commentaries on the Chumash (the Five Books of Moses), Tehillim (Psalms), and the siddur (prayer book).

In 1876, a law called the "Secession Bill" was passed. This law allowed Jews to leave a religious community without losing their religious status. Rabbi Hirsch believed that Jewish law required Orthodox Jews to separate from the main community, which was led by Reform Jews. This caused a big disagreement within the Jewish community. Some, like Rabbi Seligman Baer Bamberger, thought separation was not needed if the main community made arrangements for Orthodox Jews. This split caused a lot of pain and had effects until the Jewish community in Frankfurt was destroyed by the Nazis.

Final Years

In his last years, Rabbi Hirsch worked to create the "Freie Vereinigung für die Interessen des Orthodoxen Judentums." This was an association of independent Jewish communities. After his death, this organization became a model for the international Orthodox Agudas Yisrael movement. Rabbi Hirsch loved the Land of Israel deeply, as shown in his writings. However, he did not support the early Zionist activities of Zvi Hirsch Kalischer.

It seems likely that Rabbi Hirsch caught malaria while in Emden. This illness caused him to have fevers for the rest of his life.

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch passed away in 1888 in Frankfurt am Main and is buried there.

His son (1833–1900) was a scholar and writer. His granddaughter, Rahel Hirsch (1870–1953), became the first female professor of medicine in Prussia.

Rabbi Hirsch's Writings

Nineteen Letters

Rabbi Hirsch's "Nineteen Letters on Judaism" (Neunzehn Briefe über Judenthum) was published in 1836. It was written as if a young rabbi was writing letters to a young intellectual. The first letter, from the intellectual, asked about the challenges facing modern Jews and if Judaism was still important. The rabbi's letters answered these questions. He discussed God, people, Jewish history, and the meaning of Mitzvot (commandments).

This book had a huge impact in German Jewish communities. It has been reprinted and translated many times. It is still important today and is often studied.

Horeb

Horeb was published in 1838. Its full title means "Essays on the Duties of the Jewish People in the Diaspora." This book explains Jewish law and practices. It focuses on the deep ideas behind them. These discussions are still taught and used as references today.

The book is divided into six parts, based on Rabbi Hirsch's way of classifying the commandments. It was written during a time when the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) and Reform Judaism were starting. So, it was an effort to guide young Jews back to God's law. In Horeb, Rabbi Hirsch showed that the Torah's mitzvot are not just ceremonies. They are important duties for Jewish people. The title "Horeb" refers to Mount Horeb, another name for Mount Sinai, where the Ten Commandments were given.

Other Important Works

Rabbi Hirsch also wrote several other important works. These include:

- Jüdische Anmerkungen zu den Bemerkungen eines Protestanten (1841): A response to an anti-Jewish pamphlet.

- Die Religion im Bunde mit dem Fortschritt (1854): A response to challenges from the Reform-led "Main Community" in Frankfurt.

- Pamphlets during the Secession Debate: Das Princip der Gewissensfreiheit (1874) and Der Austritt aus der Gemeinde (1876). These discussed the idea of leaving the main Jewish community.

- Ueber die Beziehungen des Talmuds zum Judenthum (1884): A defense of Talmudic writings against false accusations.

Many of Rabbi Hirsch's writings have been translated into English and Hebrew. His collected writings, called Gesammelte Schriften or Nachalath Zwi, began to be published in 1902.

Key Ideas in His Work

Rabbi Hirsch lived after the time of Napoleon. This was a period when Jews in many European countries gained civil rights. This led to calls for reform within Judaism. A big part of Rabbi Hirsch's work focused on how Orthodox Judaism could thrive in this new era. He believed that if Jews had freedom of religion, they should use it to practice Torah laws without being pressured or made fun of.

His idea of "Austritt" (separation), meaning an independent Orthodoxy, came from his view of Judaism's place in his time. He felt that for Judaism to benefit from new freedoms, it needed to develop on its own. It should not have to agree with or support efforts to reform Judaism.

Another major part of his work explored the symbolic meaning of many Torah commandments and passages. His book Horeb (1837) largely focused on the possible meanings and symbols in religious laws. He continued this work in his Torah commentary and articles in the Jeschurun journal.

More recently, people have rediscovered his work on the Hebrew language. Much of this is in his Torah commentary. He analyzed and compared the shorashim (three-letter root forms) of many Hebrew words. He developed a system for understanding Hebrew word origins. This system suggests that letters that sound similar often have similar meanings. For example, the words Zohar (light), Tzohar (translucent window), and Tahor (purity) are related because the letters Zayin, Tzadie, and Tet sound alike. This idea is also used by the famous biblical commentator Rashi. Even though Rabbi Hirsch said his work was "totally unscientific," it has led to a modern "etymological dictionary of the Hebrew language."

While Rabbi Hirsch did not mention his influences (other than traditional Jewish sources), later writers have found ideas from the Kuzari (Yehuda Halevi), Nahmanides, and the Maharal of Prague in his works. However, most of his ideas were original.

In a 1995 edition of Hirsch's Nineteen Letters, Rabbi Joseph Elias tried to show Rabbi Hirsch's sources in Rabbinic literature. He also compared Hirsch's ideas to those of other Jewish thinkers. Elias also tried to correct some misunderstandings of Hirsch's philosophy. For example, he argued against the idea that much of Hirsch's thinking came from Kantian secular philosophy.

The Zionist movement was not founded during Rabbi Hirsch's lifetime. However, from his responses to Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer and in his commentaries, it is clear that he loved the Land of Israel deeply. But he did not support a movement to gain political independence for the Land of Israel before the Messianic Era. In later writings, he made it clear that Jewish rule depends only on God's plan.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Samson Raphael Hirsch para niños

In Spanish: Samson Raphael Hirsch para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |