Samuel Wendell Williston facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel Wendell Williston

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | July 10, 1851 Boston, Massachusetts, United States

|

| Died | August 30, 1918 (aged 67) |

| Nationality | American |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | Kansas State Agricultural College Yale University |

| Known for | Allosaurus, Diplodocus, illustrations, terrestrial origin of bird flight |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Paleontology |

| Institutions | Yale University University of Kansas University of Chicago |

| Signature | |

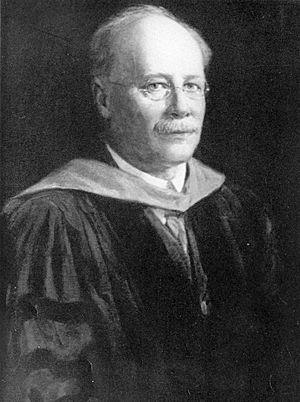

Samuel Wendell Williston (born July 10, 1851 – died August 30, 1918) was an American educator, entomologist, and paleontologist. He was the first to suggest that birds learned to fly by running on the ground, instead of by leaping from tree to tree. He was also a special expert on flies, a group of insects called Diptera.

He is also remembered for something called Williston's law. This law says that over a long time, parts of an organism, like the legs of an insect, tend to become fewer in number and more specialized for certain jobs as they evolve.

Contents

Early Life and Discoveries

Samuel Williston was born in Boston, Massachusetts. When he was a young child, his family moved to Kansas Territory in 1857. They went there to help fight against slavery. He grew up in Manhattan, Kansas, and went to high school there. He later graduated from Kansas State Agricultural College (which is now Kansas State University) in 1872.

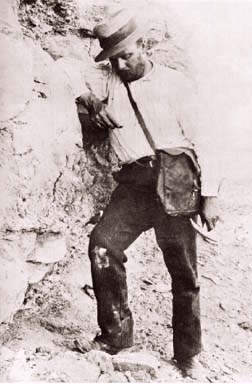

In 1874, Williston went on his first trip to hunt for fossils. He worked for Othniel Charles Marsh at Yale University. He learned a lot from Benjamin Franklin Mudge. In 1877, Williston led his own fossil hunting trip for the first time. Working with Mudge, Williston found the first fossils of the dinosaurs Allosaurus and Diplodocus. He was known for drawing very detailed pictures of the fossils he found.

In 1880, he went to Yale University as a student and later became a teacher there. Around this time, he came up with the idea that birds learned to fly by running on the ground. This was a new idea, as many people thought birds learned to fly by jumping from trees.

Williston moved back to Kansas in 1890. He became a professor of geology and anatomy at the University of Kansas. In 1899, he became the first leader (Dean) of the new University of Kansas School of Medicine. He also worked on state health and medical boards. In 1902, Williston left Kansas again. He took a job as a professor of paleontology at the University of Chicago.

Williston was a member of important science groups, like the Geological Society of America. He was also the president of the Kansas Academy of Science. In 1903, he became president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. He wrote several books, and the Smithsonian Institution now has a special fund named after him.

Williston's Work on Flies

Even though Samuel W. Williston was not officially hired as an entomologist (an insect expert), he was a respected member of the Entomological Society of America. He was a very well-known expert on how to classify and study flies (Diptera). He was the first expert on this group of insects in North America. He wrote over 50 books and papers and named more than 1250 different species of flies. His most famous books were the three editions of the Manual of North American Diptera (published in 1888, 1896, and 1908).

Understanding Williston's Law

Williston noticed something interesting about how animals change over evolutionary time. He saw that parts of animals that were repeated, like many similar legs on an insect, tended to change. Over time, these parts often became fewer in number and more specialized for different jobs.

For example, very old vertebrates (animals with backbones) had mouths with mostly similar teeth. But newer vertebrates have different kinds of teeth. These teeth are shaped for biting, tearing, or chewing food. This difference in teeth helps them eat different things. For instance, meat-eating animals (like carnivores) have sharp incisors, canines, and special tearing teeth. Animals that eat plants (like grazers) mostly have flat chewing teeth.

In 1914, Williston stated that "it is also a law in evolution that the parts in an organism tend toward reduction in number, with the fewer parts greatly specialized in function." This means that as animals evolve, they often end up with fewer body parts, but those parts become very good at specific tasks. However, not all studies have fully agreed with this idea. For example, a study of bones in fish did not always show a trend towards fewer parts. Instead, some parts showed a quick change early in the group's history, then changed more slowly.

See also

In Spanish: Samuel Wendell Williston para niños

In Spanish: Samuel Wendell Williston para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |