Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site facts for kids

|

Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site

|

|

Reconstructed forge and mill

|

|

| Location | 244 Central Street, Saugus, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Area | 9 acres (0.04 km²) |

| Architect | Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, Kehoe & Dean |

| Visitation | 11,153 (2006) |

| Website | Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000047 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | November 27, 1963 |

| Designated NHS | April 5, 1968 |

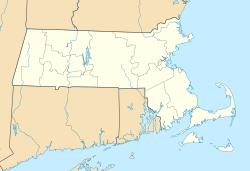

The Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site is a special place located about 10 miles (16 kilometers) northeast of Boston in Saugus, Massachusetts. It's where the very first complete iron-making factory in North America was built! This amazing factory operated between 1646 and about 1670.

Today, you can see reconstructed parts of the old ironworks. These include a blast furnace, a forge, a rolling mill, and a huge quarter-ton trip hammer. Seven large waterwheels powered the whole facility, using the force of water to turn giant wooden gears. The site also has a dock where iron could be loaded onto ships and a beautifully restored 17th-century house.

Contents

The Story of Iron Making

During the 1600s, iron was super important for everyday life. People used it to make essential items like nails, tools, cooking pots, and even weapons. But making iron was a complicated process that needed a big factory.

When English settlers first came to North America, they couldn't make iron here. All iron goods had to be shipped from England. This was expensive and took a long time, often two months by boat!

Starting the First Iron Works

A man named John Winthrop the Younger had a great idea. He thought that since the colonies had lots of raw materials, an ironworks in Massachusetts could make iron goods. These goods could then be sold in America and even back in England.

In 1641, Winthrop went to England to find people to invest money in his idea. A group called the "Company of Undertakers for the Iron Workes in New England" was formed to fund the project. Winthrop first chose a spot in Braintree, Massachusetts. Construction started in 1644, and the factory was finished in 1645. The government even gave the company a special deal: no taxes and a 21-year monopoly on making iron! However, this first ironworks didn't work out because there wasn't enough iron ore nearby, and the water supply wasn't strong enough to power the machines.

Finding the Perfect Spot in Saugus

In 1645, the investors decided to replace Winthrop with Richard Leader. Leader was a merchant who knew a lot about making iron. He looked at different locations and chose a spot on the Saugus River. This river was perfect because small boats could travel on it, and it could be dammed to create power for the machinery.

The nearby forests provided wood for making charcoal, which was needed for the furnaces. They found "bog ore" – iron ore found in swamps and riverbeds. For a special ingredient called "flux," which helps melt the iron, they discovered that a rock called gabbro from nearby Nahant worked well.

How the Saugus Iron Works Operated

The new ironworks, called Hammersmith, began making iron in 1646. It was one of the most advanced iron factories in the world at that time!

Here's what it had:

- A blast furnace to make "pig iron" and "gray iron." Gray iron was poured into molds to make things like pots, pans, and fireplace backs.

- A forge where pig iron was turned into "wrought iron." A huge 500-pound hammer shaped this iron into bars that blacksmiths would use to make finished products.

- A rolling and slitting mill that made flat pieces of iron. These were used for nails, bolts, horseshoes, and other tools.

The Iron Works ran for about 30 weeks a year and could produce one ton of cast iron every day!

The Workers

Skilled workers came from England to work at the ironworks. These workers sometimes found it hard to fit in with the strict local Puritan society. Less experienced local workers sometimes had accidents, which could be serious.

Another group of workers were indentured servants. These people worked for three to seven years without much pay in exchange for their trip to Massachusetts and basic needs like food and housing. After a big battle in Scotland in 1650, about 35 to 37 Scottish prisoners of war were sent to work at the Iron Works as indentured servants. They mostly did hard labor like chopping wood. Many gained their freedom after seven years and stayed in Massachusetts or moved to Maine, starting families.

The End of an Era

In 1650, Richard Leader left the Iron Works. John Gifford and William Aubrey took over. Even though the Iron Works made a good amount of iron, it often didn't make a profit. This was due to high labor costs and money problems. The Saugus Iron Works eventually closed around 1670.

Bringing the Iron Works Back to Life

After it closed, the site became overgrown and forgotten. In 1898, a historical marker was put up, but even that eventually got hidden by plants.

In 1915, an antique collector named Wallace Nutting bought a nearby 1680s farmhouse. He believed it was once the home of the ironmaster. Nutting restored the house and filled it with his antique collection. He even added a blacksmith's shop.

Later, a group called the First Iron Works Association (FIWA) bought the farmhouse and some of the old ironworks land. One of their directors, Louise E. du Pont Crowninshield, convinced Quincy Bent to help. Bent, a retired steel executive, was very interested in the slag pile at the site. Slag is a waste product from iron making, and it showed that an ironworks had definitely been there! Bent then convinced the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) to pay for the restoration.

Digging Up the Past

In 1948, the FIWA hired archaeologist Roland W. Robbins to find the exact location of the Iron Works. Robbins was excited to dig at such an old site, especially since there were no old maps or drawings to guide him.

His team uncovered the main parts of the Iron Works, including building foundations, the remains of the blast furnace, water ponds, and canals. They even found a 500-pound hammer and a waterwheel that powered the furnace's bellows! Biologists from Harvard University helped preserve the ancient waterwheel. In total, over 5,000 artifacts were found.

The Boston architecture firm of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, Kehoe & Dean, famous for restoring Colonial Williamsburg, was hired to rebuild the Iron Works. They used what the archaeologists found, historical documents, and some educated guesses.

The reconstructed Saugus Iron Works opened on September 18, 1954. It was a big celebration for the town's 325th anniversary!

Becoming a National Park

After it opened, the Saugus Iron Works was run as a private museum. But in 1961, the American Iron and Steel Institute said they would stop paying for its upkeep. This made the future of the site uncertain.

However, on April 5, 1968, the Saugus Iron Works became part of the National Park Service system! It was renamed the Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site. Today, the park is open seasonally, usually from spring through fall, for everyone to visit and learn about this important piece of American history.

Gallery

See also

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |