Girolamo Savonarola facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Girolamo Savonarola |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Girolamo Savonarola by Fra Bartolomeo, c. 1498, Museo di San Marco, Florence. | |

|

|

|

| Reign | November 1494 – 23 May 1498 |

| Predecessor | Piero de' Medici |

| Successor | Piero Soderini |

| Father | Niccolò di Michele dalla Savonarola |

| Mother | Elena Bonacolsi |

| Born | 21 September 1452 Ferrara, Duchy of Ferrara |

| Died | 23 May 1498 (aged 45) Florence, Republic of Florence |

| Girolamo Savonarola | |

| Congregations served | Florentine Dominican Order |

|---|---|

Girolamo Savonarola (born September 21, 1452 – died May 23, 1498) was an Italian Dominican friar and preacher. He lived in Ferrara and later became very active in Renaissance Florence. He was known for his strong beliefs and for predicting future events. He spoke out against corruption in the church and unfair rulers. He also wanted to help poor people.

In 1494, Charles VIII of France invaded Italy and threatened Florence. Many people felt Savonarola's predictions were coming true. Savonarola spoke with the French king. The people of Florence then removed the ruling Medici family. With Savonarola's encouragement, they set up a new "popular" republic. He said Florence would become a "New Jerusalem," a world center for Christianity. He started a very strict campaign to make the city more religious. Young people in Florence helped him a lot.

In 1495, Florence refused to join Pope Alexander VI's group against the French. The Pope called Savonarola to Rome, but he refused to go. He kept preaching even though the Pope told him to stop. He held large parades and "bonfires of the vanities." These bonfires were where people burned things they thought were sinful, like fancy clothes or art. In 1497, the Pope officially removed Savonarola from the Church (excommunicated him).

In April 1498, a rival preacher challenged Savonarola to a "trial by fire." This was a way to see if God supported him. The event was a disaster, and people turned against Savonarola. He and two other friars who supported him were arrested. On May 23, 1498, they were found guilty and executed in Florence's main square.

Savonarola's followers, called the Piagnoni, continued his ideas of freedom and religious change. Even though the Medici family returned to power in 1512, his ideas lived on. Some Protestants, like Martin Luther, saw Savonarola as an important person who came before the Reformation.

Contents

Girolamo Savonarola's Early Life

Girolamo Savonarola was born on September 21, 1452, in Ferrara. His parents were Niccolò di Michele and Elena. He was the third of seven children. His grandfather, Michele Savonarola, was a famous doctor and a very smart person. He helped with Girolamo's education. The family became quite wealthy from his grandfather's medical work.

After his grandfather died in 1468, Savonarola might have gone to a public school. There, he would have learned about classic writers and poets like Petrarch. He earned an arts degree from the University of Ferrara. He planned to become a doctor, like his grandfather. However, he later changed his mind about this career.

In his early poems, he wrote about his worries for the Church and the world. He started writing poems about the end of the world, like "On the Ruin of the World" (1472). He also wrote "On the Ruin of the Church" (1475). In these poems, he strongly criticized the Pope's court in Rome. Around this time, he also started thinking about a life in religion. He later said that a sermon he heard made him decide to become a friar.

Savonarola studied the writings of Augustine and Thomas Aquinas. He also studied the Bible very closely and even memorized parts of it.

On April 25, 1475, Girolamo Savonarola went to Bologna. He joined the Friary of San Domenico, which was part of the Dominican Order. He told his father in a letter that he wanted to become a "knight of Christ."

Becoming a Friar

In the convent, Savonarola promised to obey his order. After a year, he became a priest. He studied the Bible, logic, and philosophy. He also practiced preaching to other friars. He was preparing for a higher degree in theology. Even though he wrote religious works, he openly criticized how relaxed the convent had become.

In 1478, his studies were paused. He was sent to another Dominican priory in Ferrara. In 1482, instead of going back to Bologna, Savonarola was sent to be a teacher at the Convent of San Marco in Florence.

At San Marco, Friar Girolamo taught logic to new friars. He wrote guides on ethics, logic, and government. He also prepared his sermons for local churches. He noted that his preaching was not very successful at first. Florentines found his accent strange and his voice loud. They also thought his style was not elegant, especially compared to the popular humanist speakers.

One day, while studying the Bible, he suddenly had "about seven reasons" why the Church would face problems and then be renewed. He spoke about these ideas in San Gimignano in 1485 and 1486. But he didn't share these "revelations" in Florence until later.

Savonarola as a Preacher

For several years, Savonarola traveled and preached in cities and convents in northern Italy. His message was about repentance and change. His confidence and sense of purpose grew as he became more well-known. In 1490, he was sent back to San Marco in Florence.

This return was helped by Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, a famous philosopher. Pico had heard Savonarola speak and was impressed by his knowledge and faith. Pico was protected by Lorenzo the Magnificent, who was the unofficial ruler of Florence. Pico convinced Lorenzo that Savonarola would bring respect to the San Marco convent. After some delays, Savonarola returned to Florence in May or June of 1490.

Savonarola's Prophecies and Influence

Savonarola preached about the Bible, especially the First Epistle of John and the Book of Revelation. So many people came to hear him that he had to move his sermons to the cathedral. He spoke about rulers who took away people's freedom. He also criticized the rich and powerful who ignored and used the poor. He complained about the bad lives of corrupt church leaders. He called for people to change before God's punishment arrived.

Some people made fun of him, calling him an "over-excited zealot." They called his followers Piagnoni, meaning "Weepers" or "Wailers." In 1492, Savonarola warned that "the Sword of the Lord" was coming soon to Earth. He saw terrible troubles for Rome. Around 1493, he began to predict that a "New Cyrus" would come to reform the Church.

In September 1494, King Charles VIII of France entered Italy with a large army. This caused political chaos. Many people saw King Charles's arrival as proof that Savonarola's predictions were true. Charles moved towards Florence, attacking towns and threatening the city. The people of Florence drove out Piero the Unfortunate, Lorenzo de' Medici's son. Savonarola then led a group to meet the French king in November 1494. He asked Charles to spare Florence. He also urged him to take on his role as a reformer of the Church.

After a tense time, and another talk by Savonarola, the French left Florence on November 28, 1494. Savonarola then declared that by listening to his call for change, the Florentines had built a "new Ark of Noah." This ark had saved them from God's punishment. This idea suggested that Florence would become a powerful spiritual and political center.

Reforms in Florence

With Savonarola's advice, a political group called "the Frateschi" formed. They helped pass Savonarola's plans through the city councils. People who had worked closely with the Medici family were not allowed to hold office. A new constitution gave more power to the artisan class. It also allowed citizens to vote in a new parliament called the Great Council.

Savonarola pushed for a "Law of Appeal." This law limited the old practice of using exile and death as political weapons. Savonarola announced a new time of "universal peace." On January 13, 1495, he gave a famous sermon. He reminded everyone that he had started predicting things four years earlier. He claimed he had predicted the deaths of Lorenzo de' Medici and Pope Innocent VIII in 1492. He also said he predicted the French invasion. He believed God had chosen Florence, "the center of Italy," as a special city. He repeated that if the city continued to change, it would become rich, glorious, and powerful.

Savonarola wanted people to believe that Florence's power and glory came from God. In a sermon on April 1, 1495, he described a mystical journey to the Virgin Mary in heaven. He said Mary told him that Florence would be "more glorious, more powerful and richer than ever." She promised that she would protect the city. In this "New Jerusalem" (Florence), peace and unity would rule. Based on these visions, Savonarola promoted a government led by God. He declared Christ the king of Florence. He believed sacred art was good, but he was against art that was not religious.

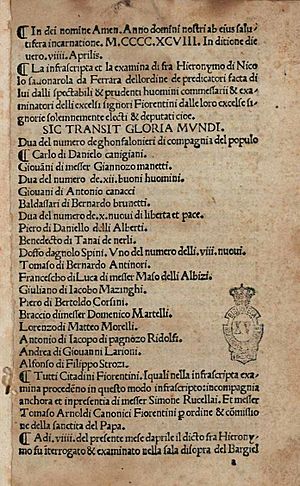

For a while, Pope Alexander VI (1492–1503) allowed Savonarola to criticize the Church. But the Pope became angry when Florence refused to join his new group against the French. He blamed Savonarola for this. The Pope and Savonarola exchanged letters, but they could not agree. Savonarola tried to convince the Pope by sending him a book. This book, Compendium of Revelations, told about Savonarola's predictions and visions. It became one of his most popular writings.

The Pope was not pleased. He ordered Savonarola to come to Rome. Savonarola refused, saying he was sick and afraid of being attacked on the way. Alexander then banned him from preaching. Savonarola obeyed for a few months. But when he felt his influence fading, he defied the Pope. He started preaching again, and his sermons became even stronger. He attacked his enemies in Florence and criticized Christians who were slow to follow his calls for change.

He made his moral campaign more dramatic with special Masses for young people. He also held parades, bonfires of the vanities, and religious plays. He and his friend, Girolamo Benivieni, wrote religious songs for the Carnival parades. These songs were still sung after his death.

Savonarola's Ideas and Legacy

Savonarola wanted the Church to return to its "early simple ways." Many Protestants see him as someone who prepared the way for the Reformation. They point to his ideas about faith, the importance of the Bible, and his care for the poor. Savonarola's writings spread widely in Germany and Switzerland. His life and death made many people see the Pope as corrupt. This led them to seek new reforms for the Church. Many, including Martin Luther, saw him as a martyr.

Savonarola's ideas on faith were similar to Martin Luther's teachings. He believed people are not saved by their own good deeds. Savonarola might have even influenced John Calvin, though this is still debated by historians.

Savonarola never left the Roman Catholic Church. He believed in its seven sacraments and that the Church of Rome was "the mother of all other churches." However, his protests against corruption and his focus on the Bible connect him to the later Reformation. He said, "I preach the regeneration of the Church, taking the Scriptures as my sole guide." He also said, "Not by their own deservings, O Lord, or by their own works have they been saved... but because it seemed good in Thy sight." These words made Martin Luther say that Savonarola's ideas were an example of true Christian theology. Savonarola respected the Pope's position, but he still criticized Pope Alexander VI and his court. He even predicted that Rome would face God's judgment.

Some Catholic historians say Savonarola was not a Protestant forerunner. They argue that most of his beliefs were still in line with Rome. However, he did inspire some Protestant reformers. He also influenced some leaders of the Counter-Reformation, which was the Catholic Church's response to the Reformation.

Excommunication and Death

On May 12, 1497, Pope Alexander VI officially removed Savonarola from the Church (excommunicated him). He also threatened Florence with an interdict if they continued to support him. Savonarola was excommunicated for speaking out against the Church and for causing trouble.

On March 18, 1498, Savonarola stopped public preaching. This was after much debate and pressure from the worried government. While excommunicated, he wrote his important work, Triumph of the Cross. This book celebrated the victory of the Cross over sin and death. It explored what it means to be a Christian. He said that loving others is the most important Christian value.

Savonarola hinted that he could perform miracles to prove his divine mission. But a rival preacher challenged him to a "trial by fire." This meant walking through fire to show God's support. Savonarola's friend, Fra Domenico da Pescia, offered to take his place. Savonarola felt he could not refuse. The trial was set for April 7. A large crowd gathered, eager to see if God would intervene. The people involved delayed the start for hours. Then, a sudden rain drenched everyone, and officials canceled the event. The crowd was angry. Savonarola was blamed for the failure. A mob then attacked the convent of San Marco.

Friar Girolamo, Friar Domenico, and Friar Silvestro Maruffi were arrested. Under pressure, Savonarola confessed to making up his prophecies. Then he changed his mind, and then confessed again. In his prison cell, he wrote meditations on Psalms 51 and 31. On the morning of May 23, 1498, the three friars were led to the main square. Before church and government officials, they were found guilty and sentenced to death.

What Happened After Savonarola's Death

The friars of San Marco kept Savonarola's memory alive. They saw him as a saint and encouraged women in convents to find inspiration in his example. They saved many of his sermons and writings. This helped keep his religious and political ideas alive. When the Medici family returned to power in 1512, they tried to stop the movement. However, Savonarola's ideas briefly returned in 1527 when the Medici were again forced out. In 1530, Pope Clement VII helped the Medici return to power. Florence then became a dukedom passed down through families.

Niccolò Machiavelli, a writer who lived at the same time as Savonarola, wrote about him in his book The Prince. He noted Savonarola's power to influence people.

Savonarola's religious ideas spread to other places. In Germany and Switzerland, early Protestant reformers, like Martin Luther, read his writings. They praised him as a martyr. They felt his ideas about faith were similar to Luther's own beliefs. In France, many of his works were translated. Savonarola was seen as someone who came before the Protestant (Huguenot) reform. However, Savonarola himself remained a Catholic. He even defended the Pope's role in his last major work. Within the Dominican Order, Savonarola was seen as a holy figure. Philip Neri, a Florentine who was educated by the San Marco Dominicans, also defended Savonarola's memory. In Wittenberg, Martin Luther's hometown, a statue of Girolamo Savonarola was put up to honor him.

In the mid-1800s, new followers of Savonarola found inspiration in his writings. They used his ideas for the Italian national movement called the Risorgimento. They focused on his political actions rather than his strict religious views. This helped bring back Savonarola's image as a fiery reformer. Many new studies and biographies were written about him. Today, scholars continue to study his life and his place in history. The Church has even considered making him a saint.

Savonarola in Culture

Music

- William Byrd used words from Savonarola's Infelix ego in his own music.

- Charles Villiers Stanford wrote an opera called Savonarola in 1884.

- Luigi Dallapiccola used text from Savonarola's writings in his 1938 work Canti di prigionia.

Stories and Films

- Many authors have written poems and novels about Savonarola, including George Eliot (Romola, 1863) and Thomas Mann (Fiorenza, 1909).

- The 1917 story "'Savonarola' Brown" by Max Beerbohm is about a playwright trying to write a play about Savonarola.

- The novel The Agony and the Ecstasy (1961) by Irving Stone shows events in Florence from the Medici family's point of view.

- Savonarola appears in the 1974 film Immoral Tales.

- In the 1976 film Network, a character compares a news anchor to a "strip Savonarola."

- The novel The Palace (1978) by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro features Savonarola as a main bad guy.

- Savonarola is a character in the historical fantasy novel The Dragon Waiting (1984) by John M. Ford.

- The novel The Birth of Venus (2003) by Sarah Dunant talks a lot about Savonarola.

- Savonarola is mentioned in the manga-anime series Gunslinger Girl (2003).

- The novel The Rule of Four (2004) by Ian Caldwell and Dustin Thomason often refers to Savonarola.

- In the novel I, Mona Lisa (2006) by Jeanne Kalogridis, Savonarola is shown negatively.

- The young adult novel The Smile (2008) by Donna Jo Napoli shows Savonarola through the eyes of a young Mona Lisa.

- In the novel Wolf Hall (2009) by Hilary Mantel, the Bonfire of the Vanities is mentioned.

- Savonarola is a main target in the video game Assassin's Creed II (2009).

- Savonarola's life is explored in the novel Fanatics (2011) by William Bell.

- In the TV series The Borgias, Savonarola is played by Steven Berkoff.

- In the Netflix series Borgia, Savonarola is played by Iain Glen.

- Savonarola is a character in the 2016 play Botticelli in the Fire by Jordan Tannahill.

- In the Rai Fiction series Medici, Savonarola is played by Francesco Montanari.

- The novel Lent (2019) by Jo Walton retells Savonarola's life.

See also

In Spanish: Girolamo Savonarola para niños

In Spanish: Girolamo Savonarola para niños