Sea of the West facts for kids

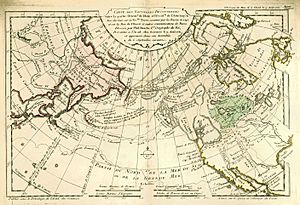

The Sea of the West, also known as Mer de l'Ouest in French, was a big mistake on many maps from the 1700s. It was thought to be a large inland sea in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. Many French maps showed this sea. People believed it was connected to the Pacific Ocean by at least one narrow waterway, called a strait. Maps showed the sea in many different shapes, sizes, and locations.

The idea of this sea came from stories about two explorers: Admiral Bartholomew de Fonte and Juan de Fuca. Juan de Fuca might have made his voyage, but his story had many made-up parts. Admiral de Fonte, however, was likely not a real person, and his journey was probably just a made-up tale. Some maps in the early 1700s showed this sea. Then, interest in it faded for a while. But in the mid-1700s, the Mer de l'Ouest suddenly reappeared on maps and became very common for several decades.

As Europeans learned more about the region, it became clear that the inland sea did not exist. By the late 1700s, the idea of the Sea of the West was no longer believed.

Contents

How the Idea of the Sea of the West Began

The story of the Sea of the West started with two main accounts. Let's look at them.

Juan de Fuca's Story

Juan de Fuca was born Ioannis Phokás in Greece in 1536. He claimed to have worked for the Spanish king for many years, traveling to the Far East. In 1587, he said he was stuck in New Spain after his ship was captured by Thomas Cavendish. Juan de Fuca then claimed that in 1592, he sailed up the western coast of North America. He said he found a strait leading to an inland sea at 47° latitude. Today, the Strait of Juan de Fuca is at 48°N, which is very close to his claim. So, it's possible he was there.

However, Juan de Fuca's description of the area, shared by Michael Lok in 1625, doesn't match what we know today. Many parts of his story are thought to be made up, either by him or by Lok. Michael Lok was important because he supported the Frobisher Expedition, which was looking for a Northwest Passage.

The Search for a Northwest Passage

Finding a way from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific was a huge goal for European countries. The journey around South America, through the Straits of Magellan, was long and dangerous. For hundreds of years, explorers dreamed of a shorter, safer route through North America. This search led to many rumors and made-up stories about new lands and passages. Imaginary voyages, like those to a Northwest Passage or to treasure islands, were easily believed.

Some early maps from the 1600s, possibly inspired by de Fuca's story, showed parts of the Pacific Ocean reaching deep into North America. One map from the late 1630s even showed a branch reaching within a few hundred miles of the East Coast. Later, Guillaume Delisle, a famous mapmaker, drew several maps between 1695 and 1700 that showed these western parts of the Pacific Ocean. His half-brother, Joseph-Nicolas Delisle, printed copies of one of these maps. Guillaume kept working on his idea of this western sea for decades. But he never officially published any maps showing the Sea of the West, even though he made many other maps.

As the king's mapmaker and a teacher to his children, Guillaume Delisle's ideas were very important. On one of his first maps, he wrote that the sea was "not yet discovered but confirmed by the report of several natives who claim to have been there." In 1716, the governor of New France even drew a map showing a water route from Lake Winnipeg to the Sea of the West. The French government wanted more exploration but wouldn't pay for it. French Canadians, however, were interested in the fur trade.

In 1731, Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye was hired to explore and find new fur trade routes. For the next twelve years, La Vérendrye's trips went as far west as Saskatchewan and Wyoming. They were looking for furs, the "River of the West," and the Sea of the West. By 1743, the French government was tired of La Vérendrye. They thought he was more interested in trading furs than exploring, so they made him resign.

Admiral Bartholomew de Fonte's Letter

In 1708, another amazing travel story appeared. An English magazine called Monthly Miscellany, or Memoirs for the Curious published a letter supposedly from Admiral Bartholomew de Fonte. The letter claimed to be translated from Spanish. It told a detailed story of a voyage in 1640 to the northwestern coast of North America. It described meetings with native people, a trip into a large inland sea, and long waterways deep inside the continent. It even suggested a connection to the eastern coasts of North America. Because the magazine was not well known, this story didn't lead to any maps for many years. But that would soon change.

The Sea of the West Appears on More Maps

For a long time, most mapmakers ignored the idea of the Sea of the West. But in 1750, Joseph-Nicolas Delisle asked Philippe Buache to draw a map with a completely new picture of the Mer de l'Ouest. This map gave credit to de Fonte for exploring the area. Buache had married Guillaume Delisle's daughter, so he inherited Guillaume's printing plates and maps. Nicolas Delisle showed this new map to the Royal Academy of Sciences, where it caused a lot of arguments.

Buache published this map in 1752. Nicolas Delisle made the arguments even bigger with his 1753 book, Nouvelles Cartes des Découvertes de l'Amiral de Fonte: et autres Navigateurs. In this book, he showed many different map ideas based on the stories of "Admiral de Fonte and other Spanish, Portuguese, English, Dutch, French, and Russian sailors who have sailed the North Seas."

Joseph-Nicolas Delisle was a very respected person. He was a "Professor of Mathematics at the Royal College" and a member of many important science groups in Paris, London, Berlin, and other cities. Because of his standing, the world of mapmaking split. Some believed in the Mer de l'Ouest, and others did not. There were many debates over a long time. Even famous people like Benjamin Franklin got involved. In 1762, Franklin wrote a long analysis of the de Fonte letter. He concluded that the differences in the story actually proved it was a real translation from Spanish, not an English made-up story. Years later, in 1783, John Adams wrote in his diary that Franklin was still talking about the de Fonte voyage, finding new reasons to believe it was true.

The idea of the Sea of the West got another boost in 1768. Mapmaker Thomas Jefferys wrote a book called The Great Probability of a North West Passage. This book analyzed the de Fonte letter. Before this time, 94 maps showed the Sea of the West. But in the next 30 years, 160 more maps showed it! More and more English mapmakers started including the sea. All these maps and the strong belief in the sea made the Spanish government start an investigation. They wanted to find out about de Fonte's voyage, which was supposedly sponsored by the Spanish king. The investigation found no record of such a person or expedition in Spanish history.

There were eight main ways the sea was drawn on maps. Most of the 239 maps showing the Mer de l'Ouest were based on one of these main ideas. It's not always clear how each idea started. But many of them were honest attempts to understand de Fonte's letter.

Some of the famous mapmakers who drew maps with the Sea of the West include:

- Jean Baptiste Nolin

- Emanuel Bowen

- Jacques-Nicolas Bellin

- Pierre Mortier

- Philippe Buache

- Leonhard Euler

- Thomas Kitchin

- Didier Robert de Vaugondy

- Thomas Jefferys

- Louis Brion de la Tour

- Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville

- Robert Sayer

- Denis Diderot

- Antonio Zatta

- Thomas Bowen

- Edme Mentelle

- Rigobert Bonne

- Jedediah Morse

- William Faden

- Charles François Delamarche

Why the Sea of the West Disappeared from Maps

By the late 1700s, more Europeans were exploring the northeast Pacific. The new information they sent back made people seriously doubt the idea of the Sea of the West. In 1778, James Cook sailed from his explorations in Hawaii to the coast of what is now Oregon. He then sailed along the entire northwest coastline, through the Bering Strait, and into the Chukchi Sea in northern Alaska.

Cook's explorations were not perfect, but his discoveries (and what he didn't discover) quickly changed maps. His work helped to map the coastlines of what are now southern Alaska, British Columbia, Oregon, and Washington State. This new information, combined with details from Russia about Vitus Bering's explorations years earlier, made it clear. The chances of finding either a Northwest Passage or a large sea in the Pacific Northwest were very small.

Information didn't always travel fast or completely. Map publishers sometimes didn't know if new discoveries were true. Also, they didn't want to spend money to update their maps. So, even after Cook's reports became widely known, some maps still showed the Sea of the West. The last original map that tried to show the sea as real appeared in 1790. It was in John Meares's book, Voyage Made in the Year 1788 and 1789, From China to the North West Coast of America. This map showed what looked like Vancouver Island as a kind of shield, with a vague sea behind it.

However, Captain George Vancouver's detailed maps from his voyage in 1791–1792 left no room for doubt. The Sea of the West was a myth. Still, a few maps showing the sea continued to appear until about 1810.

See also

In Spanish: Mar del Occidente para niños

In Spanish: Mar del Occidente para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |