Selk'nam people facts for kids

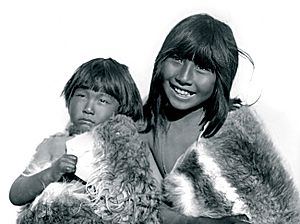

Selk'nam children, 1898

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,761 (Argentina, 2010 est.) 1,144 (Chile, 2017) |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Argentina and Chile (294 in Tierra del Fuego). At least 11 live in United States |

|

| Languages | |

| Spanish, formerly Selk'nam (Ona), One speaker in Chile. |

|

| Religion | |

| Animism, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Haush, Tehuelche, Teushen |

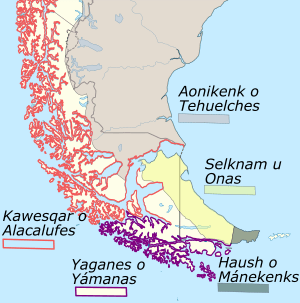

The Selk'nam, also known as the Onawo or Ona people, are an native group from the Patagonia region. This area is in southern Argentina and Chile, including the Tierra del Fuego islands. They were one of the last native groups in South America to meet European settlers. This happened in the late 1800s. In the mid-1800s, there were about 4,000 Selk'nam people. By 1930, their numbers had dropped to just over 100.

For a long time, many people thought the Selk'nam tribe was gone in Chile. But the Selk'nam people are still here today. When settlers, gold miners, and farmers came to Tierra del Fuego, it led to a terrible time called the Selk'nam genocide.

The Selk'nam are mostly known for living in the northeastern part of Tierra del Fuego. But they likely first came from the mainland. Thousands of years ago, they traveled by canoe across the Strait of Magellan. Their land might have reached as far as the Cerro Benítez area in Chile.

Contents

Selk'nam History

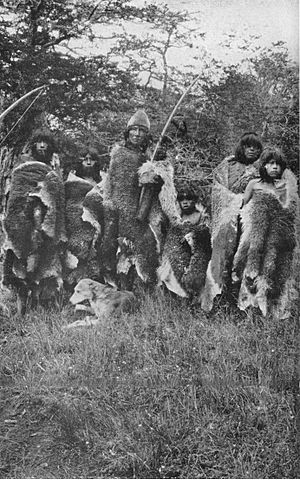

The Selk'nam were traditionally nomadic people. This means they moved from place to place. They hunted animals for food and survival. Sometimes, they also fished when the tide was low. They wore very little clothing, even though the weather in Patagonia was cold. They shared Tierra del Fuego with the Haush (Manek'enk) people, who were also nomadic. The Yahgan (Yámana) lived along the southern coast.

First Meetings with Europeans

In 1599, a Dutch fleet led by Olivier van Noort sailed into the Strait of Magellan. They had a fight with the Selk'nam, and about forty Selk'nam people died. This was the most violent event recorded in the strait at that time.

James Cook met people in Tierra del Fuego in 1769. They used pieces of glass for their arrowheads. Cook thought the glass might have been a gift from a French explorer, Louis Antoine de Bougainville. This shows there might have been earlier meetings. Glass arrowheads became more common as the Selk'nam met Europeans more often.

The Selk'nam did not have much contact with Europeans until the late 1800s. At this time, settlers came and built large ranches (called estancias) on Tierra del Fuego. This took away the Selk'nam's traditional hunting grounds. The Selk'nam did not believe in private property. So, they hunted the sheep on the ranches, thinking they were wild animals. The ranch owners saw this as stealing. They hired armed groups to hunt and kill the Selk'nam. This terrible time is now known as the Selk'nam genocide.

Salesian missionaries tried to help and protect the Selk'nam culture. Father José María Beauvoir explored the region. He studied the native cultures and languages between 1881 and 1924. He created a dictionary of the Selk'nam language with 4,000 words. He also wrote down 1,400 phrases. This was published in 1915. He believed the Selk'nam language was connected to the Tehuelche language.

German scientist Robert Lehmann-Nitsche also studied the Selk'nam. However, he was later criticized for studying Selk'nam people who had been taken and shown in circuses.

Europeans often commented on how tall the Selk'nam were. Early records called them "giants." In 1897, Frederick Cook wrote that their average height was six feet. Some individuals were even six and a half feet tall.

Relations with Europeans in the Beagle Channel area were sometimes friendlier. Thomas Bridges was an Anglican missionary in Ushuaia. He was given a large piece of land by the Argentine government. There, he started Estancia Harberton. His son, Lucas Bridges, helped the local cultures a lot. Like his father, he learned the languages of different groups. He tried to give the native people space to live their traditional lives. But changes were too strong for the native tribes. Many died as their way of life was destroyed. Lucas Bridges' book, Uttermost Part of the Earth (1948), shares a kind look into the lives of the Selk'nam and Yahgan.

Journalist John Randolph Spears wrote about Europeans living in Tierra del Fuego. He said:

It is plain that the Ona is an aggressive warrior toward the whites only because of ill-treatment. […] Damnable ill-treatment on the part of the whites is at the bottom of all the Ona aggressiveness – and Ona suffering.

The Selk'nam Genocide

The Selk'nam genocide was a terrible time when many Selk'nam people were killed. This happened from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. The Selk'nam population was about 4,000 in the 1880s. By the early 1900s, it had dropped to only 500 people.

In 1879, gold was found in the rivers of Tierra del Fuego. Many settlers and foreigners came to the island hoping to get rich. This caused conflicts with the native people. However, the gold quickly ran out.

Ranching became a big problem in the Magellanic colony. The government knew about the native group's struggles. But they supported the ranchers. They saw the Selk'nam as a barrier to "progress" and "civilization." Ranch owners often hired armed groups to kill the Selk'nam. They saw the Selk'nam as a big problem for their businesses. Ranch workers later confirmed that these killings happened often.

The owners of the Company for the Exploitation of Tierra del Fuego tried to hide their actions. They wanted to avoid questions and lower their bad reputation. Salesian missionaries spoke out against the ranchers' actions. However, the missions also accidentally contributed to the end of native cultures.

By the 1890s, the Selk'nam's situation was very bad. Farms and ranches took over much of their land in the north. Many native people, hungry and hunted by settlers, fled south. This area was already home to other native groups who strongly protected their land. So, fights over land became more intense.

The large ranch owners tried to force the Selk'nam out. Then, they started a campaign to kill them all. The Argentine and Chilean governments were involved in this. Companies paid people a reward for each dead Selk'nam. They would ask for a pair of hands or ears, or later, a whole skull. They paid more for a woman's death than a man's. The Selk'nam's problems got worse when religious missions were built. These missions moved them by force, which disrupted their lives. They also accidentally brought deadly diseases.

The killing of Selk'nam continued into the early 1900s. Chile moved most of the Selk'nam in their territory to Dawson Island in the mid-1890s. They were kept at a Salesian mission. Argentina finally allowed Salesian missionaries to help the Selk'nam. They tried to make them live like Europeans. This completely stopped their traditional culture and way of life.

Later disagreements between Governor Manuel Señoret and the head of the Salesian mission, José Fagnano, made things worse for the Selk'nam. Long arguments between government officials and priests did not help solve the problems of the native people. Governor Señoret supported the ranchers and did not care much about what happened in Tierra del Fuego.

Two Christian missions were set up to teach the Selk'nam. They were meant to give the native people homes and food. But they closed because so few Selk'nam were left. Thousands had lived there before Europeans arrived. By the early 1900s, only a few hundred remained.

In 1896, Alejandro Cañas thought there were 3,000 Selk'nam. Martín Gusinde, an Austrian priest and scientist, studied them in the early 1900s. In 1919, he wrote that only 279 Selk'nam were left. In 1945, missionary Lorenzo Massa counted 25. In May 1974, Ángela Loij, the last full-blood Selk'nam, died. However, there are still descendants with some Selk'nam ancestry. The Argentine census of 2010 found 294 Selk'nam (Ona) living on Tierra del Fuego island.

Selk'nam Culture and Beliefs

Missionaries and scientists in the early 1900s gathered information about Selk'nam culture, religion, and traditions. They tried to help preserve their way of life.

Hunting and Food

The Selk'nam traditionally ate a lot of guanaco. They hunted these animals using bows and arrows, and also with bolas (throwing ropes with weights). The guanacos in Tierra del Fuego were bigger than those in Patagonia. The Selk'nam used guanaco hides to build shelters, make bags, and create clothing. They also fished during low tides using spears. They mostly caught eels, but they valued fish like róbalos more. In the south of the island, birds were also part of their diet.

The Selk'nam also used the Fuegian dog to help them hunt. This dog was a tamed type of culpeo (a South American fox). Some early observers didn't see the dogs being useful for hunting. But others, and later research, confirmed they were used. Everyone agreed that the dogs also kept the Selk'nam warm in their shelters. They would sleep close together around the people.

Language

The Selk'nam spoke a Chon language. Missionary José María Beauvoir created a dictionary of the Selk'nam language. The last people who spoke the language fluently died in the 1980s.

Body Art

For special events like initiation ceremonies, weddings, and funerals, the Selk'nam would paint their bodies. They especially painted their faces. The main colors they used were red, black, and white.

Religion and Beliefs

The Selk'nam had a complex system of beliefs. This included a creation myth about how the world began. Temáukel was the name of a powerful spirit they believed kept the world in order. The creator of the world was called Kénos or Quénos.

The Selk'nam also had people who acted like shamans. These people, called xon (pronounced "hon"), were believed to have special powers. For example, they could control the weather.

Hain: Coming-of-Age Ceremony

The Selk'nam male initiation ceremony was called Hain. This was a special event where young boys became adults. Nearby native groups, the Yahgan and Haush, had similar ceremonies.

Young males were called into a dark hut. There, "spirits" would attack them. These "spirits" were actually men dressed up as supernatural beings. Children were taught to believe in and fear these spirits. They were threatened by them if they misbehaved. In this ceremony, the boys had to unmask the spirits. When they saw that the spirits were human, they were told a story about how the world was created, linked to the sun and moon. They also learned that in the past, women used to dress as spirits to control men. When men found out, they then pretended to be spirits to scare the women. The men believed the women never found out the masked men weren't real spirits.

The ceremonies in later times used this idea in a playful way. After the first day, other ceremonies and rituals took place. Males would show their "strength" by fighting spirits (who were other men). The women supposedly didn't know this. Each spirit was played with special actions, words, and movements. This way, everyone could recognize them. The best spirit actors from past Hain ceremonies were asked to play spirits again.

Besides these plays of old myths, the Hain also tested young males. They were tested for courage, cleverness, resisting temptation, handling pain, and overcoming fear. It also included long lessons to train the young men for their future responsibilities.

Before Europeans arrived, the Hain ceremonies lasted a very long time. Sometimes, they even lasted a year. They would end with a final fight against the "worst" spirit. Usually, Hain ceremonies started when there was plenty of food. For example, if a whale washed up on the coast. At these times, all the Selk'nam groups would gather in one place, with separate camps for men and women. "Spirits" sometimes went to the women's camps to scare them. They also moved around and acted in ways that matched their characters.

The last Hain was held in one of the missions in the early 1900s. Missionary Martin Gusinde took photographs of it. It was a shorter and smaller ceremony than in the past. The photos show the "spirit" costumes the Selk'nam made and wore. Gusinde's book The Lost Tribes of Tierra Del Fuego (2015) shows these pictures.

Marriage and Mourning

Besides decorating faces for weddings, Gusinde also saw a tradition for marriage proposals. A man would make a bow and quietly give it to the woman he wanted to marry. This happened in front of her family's elders.

After someone died, their family would light a large fire. They would sing and dance. The person who died would then be wrapped in a guanaco cape. They would be buried as soon as possible. There was also a tradition of burying people in hollows or tree roots. They made sure the person could not be seen once they were placed there. The Selk'nam did not bury items with the deceased.

Selk'nam Today

Photographs of Selk'nam people taken by missionaries are shown at the Martin Gusinde Anthropological Museum in Puerto Williams. There are also books about them, including Selk'nam stories and a dictionary of their language. Because missionaries met them early, much more information was gathered about the Selk'nam than about other groups in the region.

Austrian priest and scientist Gusinde also tried to collect information about other local people. But he found their numbers were much smaller. He could write more about traditional Selk'nam culture because the Selk'nam people were still living it in the 1900s.

The Comunidad Rafaela Ishton group was formed in the 1980s. They fought for the Selk'nam to be recognized and for their rights in Argentina. In 1994, the government recognized them as an indigenous people. The 2010 census in Argentina found 2,761 people who identified as Selk'nam across the country. 294 of them lived in the province of Tierra del Fuego, Antarctica and South Atlantic Islands.

In the 2017 Chilean census, 1,144 people said they were Selk'nam. The descendants of the Selk'nam are working to bring back and create their culture. They do not see themselves or their people as gone. The Corporación Selk'nam worked to change a law. On June 27, 2020, the Chamber of Deputies of Chile changed the law. It recognized the Selk'nam as one of Chile's indigenous peoples. Then, on September 5, 2023, the National Congress of Chile recognized the Selk’nam as one of the 11 original peoples of Chile. They accepted them as a living community. Members of parliament said they were sorry for the role the Chilean and Argentinean governments played in the killings of native people.

As of 2023, the bones of 14 Selk'nam people are kept in the collection of the Natural History Museum Vienna.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Selknam para niños

In Spanish: Selknam para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |