Siege of Valenciennes (1676–1677) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Valenciennes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Dutch War | |||||||

Prise de Valenciennes, 17 mars 1677, oil on canvas by Jean Alaux, 1837, Galerie des batailles, Palace of Versailles |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 35,000 maximum | 1,150 initially 2,000–3,000 auxiliaries |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The Siege of Valenciennes was a battle that happened from February 28 to March 17, 1677. It was part of the Franco-Dutch War. During this time, the city of Valenciennes, which was then in the Spanish Netherlands, was attacked by a French army. This army was led by the Duc de Luxembourg.

Before the siege, Valenciennes and another city called Cambrai were cut off from supplies. This was done by a tight blockade during the winter of 1676 to 1677. The French army had better ways to get supplies, which meant they could start fighting much earlier than their enemies. The siege of Valenciennes officially began on February 28. A famous French military engineer, Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, was in charge of the operations. The city gave up on March 17. Later, in August 1678, Spain officially gave Valenciennes to France as part of the Treaty of Nijmegen.

Contents

Why the Siege Happened

The Start of the Franco-Dutch War

In an earlier war (1667–1668), France had taken over most of the Spanish Netherlands and a Spanish area called Franche-Comté. However, the French King Louis XIV gave back most of these lands. He did this because of pressure from an alliance of countries called the Triple Alliance. This alliance included the Dutch Republic, England, and Sweden.

To break up this alliance, Louis XIV secretly paid Sweden to stay neutral. He also made a secret agreement with England in 1670, called the Treaty of Dover. This agreement meant England would join France against the Dutch.

The Franco-Dutch War started in May 1672 when France invaded the Dutch Republic. At first, it looked like France would win easily. But the Dutch managed to hold their ground. Other countries became worried about France's growing power. So, Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia, Emperor Leopold, and Charles II of Spain decided to help the Dutch.

France kept the Dutch fortress of Maastricht but pulled its troops out of the Netherlands in 1673. New fighting then started in other areas, like the Rhineland and the Spanish Pyrenees.

Changes in the War

By early 1674, France's position became weaker. Denmark-Norway joined the alliance against France in January. Then, in February, England and the Dutch Republic made peace with each other through the Treaty of Westminster.

Despite this, France managed to take back Franche-Comté by the end of 1674. They also gained a lot of land in Alsace. The main goal for France now was to make their new borders stronger. The Allied countries struggled to fight back effectively in Flanders. This was partly because of power struggles in Madrid, where Spain's control over the Spanish Netherlands was not very strong.

Peace talks began in Nijmegen in 1676. But King Louis XIV wanted to attack first and win more land. This way, he could negotiate from a stronger position. The French quickly captured several towns: Condé-sur-l'Escaut, Bouchain, Maubeuge, and Bavay. Taking Condé and Bouchain allowed them to block off Valenciennes and Cambrai. French cavalry fought small battles with the Spanish soldiers and destroyed villages around these towns.

Marshal Schomberg, who led the French army in Flanders, suggested taking Cambrai in August. But he was ordered to go help at Maastricht, which the Dutch were trying to capture.

French Plans for 1677

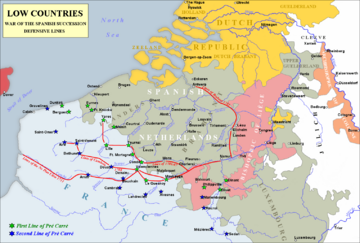

The plan for 1677 was to capture Valenciennes, Cambrai, and Saint-Omer. If France took these cities, it would complete what Louis XIV called his frontière de fer, or "iron border." He believed this would make the Dutch feel they had no reason to keep fighting.

To confuse his enemies, King Louis XIV traveled to Metz on February 7. There, he looked over the Army of the Moselle, which was now led by Schomberg. Over the winter, Marquis de Louvois set up supply points along the border with the Spanish Netherlands. This allowed the French to start their military campaign in February, a month earlier than usual. In late February, a group of 12,000 French soldiers began to besiege Saint-Omer. At the same time, the main army of 35,000 men, led by the Duc de Luxembourg, surrounded Valenciennes. King Louis XIV joined them there.

The Battle for Valenciennes

Valenciennes was located on the Rhonelle river, which flows into the Scheldt river. The Scheldt was a very important trade route that led to the sea at Antwerp. Before trains were invented, most goods and supplies were moved by water. Because of this, battles often focused on controlling these waterways.

The Spanish governor of Valenciennes was Henri de Melun, Marquis de Richebourg. He was an experienced soldier. He had about 1,150 regular soldiers, plus two to three thousand local helpers. They also had enough food and weapons.

Richebourg's situation was very difficult without help. The French had started their attack early, thanks to Louvois. This meant the Dutch army was still getting their troops and supplies ready. It was understood that even the best-defended city could not hold out forever. So, Richebourg's goal was to keep the French army busy for as long as possible.

The French military engineer, Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, led the siege operations. He used a new method called the "siege parallel" for the first time since it was used in Maastricht in 1673. The bombing of the city began on March 1. However, heavy rain delayed the building of the siege works. For good publicity, King Louis XIV often appeared at important sieges. He joined Luxembourg at Valenciennes, along with other commanders like his brother, Philippe of Orléans.

Work on the trenches finally started on March 8. These trenches were being dug to prepare for an attack on the Porte d'Anzin. This was the strongest part of the city's defenses, but the ground there was the driest. By March 16, Vauban felt they were close enough to launch an attack. He suggested they attack during the day. Normally, attacks were done at night. But Vauban argued that a daytime attack would surprise the defenders. It would also allow the attacking soldiers to work together better.

His plan was approved. The French cannons kept firing all night on March 16 and 17. An attack force of 4,000 soldiers moved into the trenches. This group included the special Musketeers of the Guard. At 9:00 a.m. on March 17, the attackers formed two groups and stormed the city walls. They completely surprised the defenders and quickly took over. They captured a bridge over the Rhonelle river, which controlled access to the main city.

Both sides wanted to avoid too much damage. Louis XIV planned to make Valenciennes part of France. Also, according to the rules of siege warfare, a city would not be looted if its defenders gave up once a "practicable breach" (a hole big enough to enter) was made. Richebourg quickly surrendered. Luxembourg then pulled back the attacking troops after the city council agreed to pay a ransom.

What Happened Next

After Valenciennes surrendered on March 17, the main French army moved on to Cambrai. William of Orange tried to help Saint-Omer, but his forces were defeated at the Battle of Cassel on April 11. Cambrai surrendered on April 17, and Saint-Omer followed on April 20.

The French army's excellent supply system allowed them to gain ground early in the fighting season. They could do this before the Allied armies were fully ready. The capture of Valenciennes and Cambrai mostly completed France's goals for 1677 in Flanders.

Peace talks at Nijmegen became more urgent in November. This was after William of Orange married his cousin Mary, who was the niece of Charles II of England. An alliance between England and the Dutch to defend each other was formed in March 1678. However, English soldiers did not arrive in large numbers until late May. Louis XIV used this chance to capture Ypres and Ghent in early March. He then signed a peace treaty with the Dutch on August 10.

The war with the Dutch officially ended on August 10, 1678, with the signing of the Treaties of Nijmegen. Even so, a combined Dutch-Spanish army attacked the French at Saint-Denis on August 13. The agreement made sure Spain kept Mons. On September 19, Spain signed its own treaty with France. Spain gave up Saint-Omer, Cassel, Aire, Ypres, Cambrai, Valenciennes, and Maubeuge to France.

Except for Ypres, which was returned to Spain in 1697, this set France's northern border close to where it is today. The Treaties of Nijmegen marked the highest point of France's expansion under King Louis XIV.

Sources