Skerryvore facts for kids

| Gaelic name | An Sgeir Mhòr |

|---|---|

| Meaning of name | The Great Skerry |

| OS grid reference | NL841265 |

| Coordinates | 56°19′30″N 7°06′40″W / 56.325°N 7.111°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Inner Hebrides |

| Area | 26 m2 (280 sq ft) |

| Highest elevation | 3 m (10 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Argyll and Bute |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

Skerryvore is a small, remote island off the west coast of Scotland. Its name comes from the Gaelic words An Sgeir Mhòr, which mean "The Great Skerry" (a skerry is a small, rocky island). Skerryvore is about 12 miles (19 kilometres) southwest of the island of Tiree.

Skerryvore is most famous for its lighthouse. This amazing lighthouse was built between 1838 and 1844 by Alan Stevenson. It was a very difficult project! At 156 feet (48 metres) tall, it is the tallest lighthouse in Scotland. The lighthouse was first run by people living on Tiree, then later from Erraid, near Mull. Because the lighthouse was so far away, the keepers who worked there received extra payments. The light shone brightly from 1844 until a fire in 1954 stopped it for five years. The lighthouse became fully automated in 1994, meaning no people live there anymore.

Contents

What is Skerryvore Made Of?

Long, long ago, in prehistoric times, the rocks of Skerryvore were covered by huge sheets of ice. These ice sheets spread from Scotland far into the Atlantic Ocean. When the ice melted about 20,000 years ago, sea levels were much lower. It's thought that Skerryvore was once part of a much larger island that included Tiree and Coll.

As sea levels slowly rose, Skerryvore became isolated. It is now a barrier of many metamorphic rocks that stretch for 8 miles (13 kilometres). These rocks are very old, formed in the Precambrian eon. They are some of the oldest rocks in Europe! The waves have made the rocks smooth, and sea spray constantly hits them. There is also a magnetic anomaly in the area, which can affect ship navigation.

Building the Lighthouse

Why Was a Lighthouse Needed?

Between 1790 and 1844, more than thirty ships crashed in the Skerryvore area. This showed how dangerous the rocks were. Robert Stevenson, who was the chief engineer for the Northern Lighthouse Board, visited the reef in 1804. He said a beacon was definitely needed. In 1814, he returned with Sir Walter Scott. Scott described Skerryvore as a "long ridge of rocks (chiefly under water), on which the tide breaks in a most tremendous style." He thought it would be a very lonely place for a lighthouse, even more so than the Bell Rock or Eddystone.

An Act of Parliament was passed to allow the lighthouse to be built. But things moved slowly. In 1834, Robert Stevenson came back with his son, Alan. They found that the best spot for the lighthouse was a rock that was only 280 sq ft (26 m2) at low tide. They calculated that any tower built there would need to withstand huge wave forces. Robert Stevenson insisted that only a strong stone tower would be safe.

The Northern Lighthouse Board was worried about the high cost, which was estimated at £63,000. They sent a special committee to visit the site. On their way, a fire broke out in their ship's boiler room! This scary experience might have convinced them that a lighthouse was truly necessary.

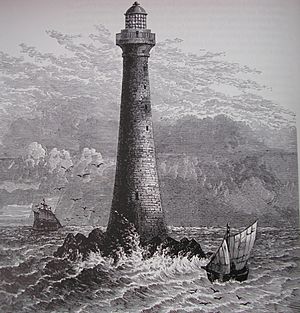

Alan Stevenson was chosen as the engineer for the project. He was only 30 years old. He designed a tower 156 feet (48 m) high, with a wide base of 42 feet (13 m) that narrowed to 16 feet (4.9 m) at the top. The bottom part of the lighthouse would be solid. The whole structure would weigh 4,308 long tons (4,377 tonnes). It would be the tallest and heaviest lighthouse ever built at that time, with 151 steps to the top.

The Shore Station

Hynish on Tiree was the main base for building the lighthouse. It was close to Skerryvore. In 1837, work began there. Large granite blocks were brought from Mull, then cut and shaped at Hynish. These blocks were then shipped to the reef. Cottages for the lighthouse keepers were built in 1844, along with a large pier and a tall granite tower. This tower was used to send signals to and from Skerryvore.

Building the Barracks and Foundation

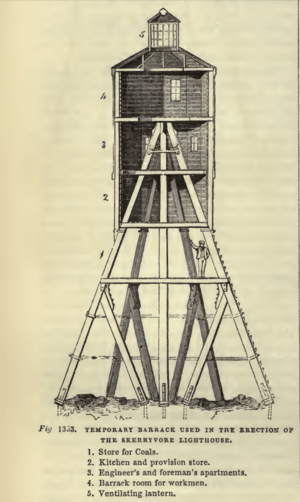

In 1838, a 150-ton steamer was built in Leith to carry workers and materials to the reef. Skerryvore is 50 miles (80 km) from the mainland, making the journey difficult. The first step on Skerryvore itself was to build a wooden barrack (a temporary home) for 40 men. It had six legs and was placed on top of the rock.

Work started on August 7, 1838. Stevenson and 21 workers began to unload the barrack. But after only two days, a storm forced them to leave. They could not return for six more days. The men worked 16 hours a day. Many preferred to sleep on the wet rocks rather than on the constantly moving ship.

The season ended on September 11, with the barrack legs secured but not the main structure. Less than two months later, a gale destroyed the barrack! Four months of work were lost. Stevenson immediately went to inspect the damage. He decided to build a stronger, but identical, replacement. Work began again in April 1839. By early September, the new barrack stood 60 feet (18 m) above the rock. It had a kitchen, cabins for Stevenson and his foreman, and sleeping quarters for 30 to 40 men.

Work on the lighthouse foundations continued until September 30. They used 296 charges to remove 2,000 long tons (2,000 tonnes) of rock. The rock was so hard that it was four times harder to drill than Aberdeenshire granite. By June 1840, 4,300 blocks had been shaped. The stone came from quarries on Mull. The largest blocks weighed over 2+1⁄2 long tons (2.5 t). Each block needed very precise shaping, sometimes taking 320 hours of work!

Building the Tower

| Deactivated | 1954-1959 |

|---|---|

| Tower shape | tapered cylindrical tower with balcony and lantern incorporating heeper's quarters |

| Markings / pattern | unpainted tower, black lantern |

| Fog signal | one blast every 60 s. |

The new barrack survived the winter storms of 1839–40. Work on the tower began on April 30, 1840. The new steamer Skerryvore brought the carefully shaped blocks to the site. The first block was laid by John Campbell, 7th Duke of Argyll on July 4. His son George later described the perfectly level and smooth circular floor, 42 ft wide, that was created in the middle of the rough rock.

Soon, up to 95 blocks arrived from Hynish each day. But the weather was still a challenge. Sometimes, the steamer could not reach the reef for weeks, and supplies ran low. By autumn, 800 tons of granite had been laid, standing 8 feet 2 inches (2.49 m) high. Craftsmen continued to work on blocks at Hynish all winter. The first three layers of the base were made of hard Hynish gneiss, and the rest was granite from Mull.

Building continued through 1841–42. A crane lifted the huge blocks as the tower grew taller. The last block was put in place in July 1842. Robert Stevenson, who was 70 years old, visited the site for his last inspection. The walls at the base are 9.5 feet (2.9 m) thick, and 2 feet (0.61 m) thick at the top. The lighthouse has nine rooms, each 12 feet (3.7 m) wide, below the lightroom. The total cost of the project was £86,977. It's amazing that not a single life was lost during the construction!

Finishing the Lighthouse

The final work in 1843 was fitting out the inside of the lighthouse. Alan Stevenson was now the chief engineer, and his brother Thomas oversaw the final stages. The light itself was built by John Milne of Edinburgh. It had eight lenses that spun around a lamp. The machinery was ready by early 1844. But bad weather meant it was seven weeks before anyone could land on the rock. The lamp was finally lit on February 1, 1844. It shone without stopping for the next 110 years.

Skerryvore lighthouse is considered one of Alan Stevenson's greatest achievements. It is praised for both its engineering and its beauty. His nephew Robert Louis called it "the noblest of all extant deep-sea lights." Many people say Skerryvore is the most graceful lighthouse in the world.

Lighthouse Keepers

The reefs around Skerryvore are so dangerous that ships usually avoid the area. Even after the lighthouse was built, landing on the rock was very difficult. The easiest landing spot is Riston's Gully, which is near the tower. It's like trying to climb the side of a bottle! A system of ropes and a derrick was installed to help with these dangerous landings. From 1881 to 1890, Skerryvore was the stormiest part of Scotland, with 542 storms lasting over 14,000 hours. One keeper even lost his hearing for weeks after being thrown by a lightning strike.

James Tomison, a keeper in 1861, wrote about the many birds that flew around the tower during migrations. A fog bell was also installed, one of only two in Scotland at the time.

Because of the tough conditions, keepers received extra payments. Some veterans liked the remote location. John Nicol, a principal keeper from 1890–1903, was involved in a dramatic rescue in 1899. The ship Labrador ran aground nearby. Two lifeboats made it to Mull, but one with eighteen passengers reached the lighthouse. The keepers looked after them for two and a half days until they could be taken to the mainland. No lives were lost, and Nicol and his assistants were praised for their bravery.

John Muir, who was a keeper from 1902 to 1914, helped finish a new "landing grating," a metal walkway that made landings possible in very bad weather. He also baked his own bread and made beautiful inlaid furniture.

Later Events

Many important people visited the lighthouse over the years. William Chambers, the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, visited in 1866. He learned about the signal system: every morning, a ball was hoisted at the lighthouse to show that all was well. If no signal was given, a ball was raised at Hynish to ask if something was wrong. If there was still no reply, a ship would sail to the lighthouse. Chambers was told that waves sometimes reached the first window, about 60 feet (18 m) high, but the building never shook.

Skerryvore looks similar to Dubh Artach, another lighthouse 20 miles (32 km) to the southeast. So, in 1890, the Northern Lighthouse Board painted a distinctive red band around Dubh Artach to tell them apart.

The Hynish Shore Station was useful during construction. But its small harbor didn't offer much shelter for ships. So, in 1892, the operations moved to Erraid, near the Isle of Mull. The land and buildings on Tiree were sold. A paddle steamer called Signal was based at Erraid for relief operations. The shore station later moved to Oban in the 1950s.

During World War II, in July 1940, a German plane dropped bombs near the rock. The explosion cracked two lantern panes and broke one of the lamps.

A serious fire started on the seventh floor on March 16, 1954, and spread downwards. The keepers had to escape onto the rocks. They were rescued the next day. The fire damaged the lighthouse's inside and structure. Temporary lights were used while it was rebuilt. Three new generators were installed to provide electric light. The lantern was lit again on August 6, 1959.

In 1972, a helipad was built so that relief trips could be made by helicopter, avoiding dangerous sea landings. The lighthouse has been fully automated since March 31, 1994. It is now monitored by radio from Ardnamurchan lighthouse.

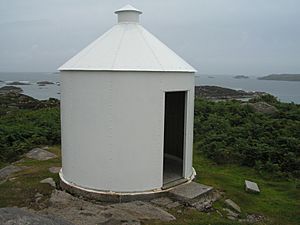

The Hynish tower on Tiree has been turned into the Skerryvore Lighthouse Museum. The pier has also been restored. You can even visit Skerryvore today with Tiree Sea Tours!

See also

In Spanish: Skerryvore para niños

In Spanish: Skerryvore para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |