Juana Inés de la Cruz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Juana Inés de la Cruz

|

|

|---|---|

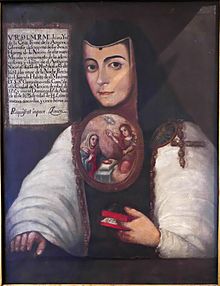

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera

|

|

| Native name |

Doña Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana

|

| Born | Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana 12 November 1648 San Miguel Nepantla, New Spain (near modern Tepetlixpa, Mexico) |

| Died | 17 April 1695 (aged 46) Mexico City, New Spain |

| Resting place | Convent of San Jerónimo, Mexico City |

| Pen name | Juana Inés de la Cruz |

| Occupation | Nun, poet, writer, musician composer |

| Language | Spanish, Nahuatl, Latin |

| Education | Self taught until the age of twenty-one. (1669) |

| Period | 17th century Nun |

| Literary movement | Baroque |

| Years active | ~1660 to ~1693 |

| Notable works |

|

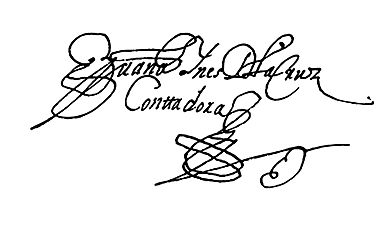

| Signature | |

|

|

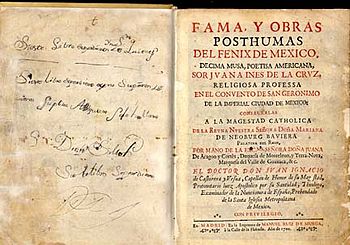

Doña Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana, better known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (born November 12, 1648 – died April 17, 1695), was an amazing Mexican writer, thinker, composer, and poet. She was a Hieronymite nun during the Baroque period. People called her "The Tenth Muse" or "The Phoenix of America" because of her important work in the Spanish Golden Age. She was like a bright flame that rose up against old ways of thinking.

Sor Juana lived in Mexico when it was a colony of Spain. She started learning at a very young age and could speak Latin fluently. She also wrote in Nahuatl, an Aztec language. She became known for her smart ideas even as a teenager. Sor Juana taught herself by reading books in her own library, which she got from her grandfather.

In 1667, she became a nun. In the convent, she wrote poems and stories about things like love, nature, feminism (equal rights for women), and religion. She made her nun's room a place where smart women from New Spain could meet and talk. She spoke out against how men sometimes treated women unfairly. This led to some problems with church leaders. In 1694, she had to sell her books and focus on helping the poor. She died the next year from a sickness while caring for other nuns.

For a long time, people didn't talk much about Sor Juana. But then, Octavio Paz, a famous writer, helped everyone remember how important she was. Today, many people see Sor Juana as an early feminist. They study her work to learn about topics like women's rights to education and how writing can help women.

Contents

Life of Sor Juana

Her Early Years

Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana was born in San Miguel Nepantla, a town near Mexico City. This town is now called Nepantla de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz in her honor. She was born to a Spanish officer father and a wealthy Mexican mother. She grew up on her grandfather's large farm called Panoaya.

As a child, Inés loved to read. She would often hide in the farm's chapel to read books from her grandfather's library. Girls were not usually allowed to do this back then. By the age of three, she had already learned to read and write Latin. By five, she could do math. When she was eight, she wrote a poem about a religious event called the Eucharist. By her teenage years, she understood Greek logic and was teaching Latin to younger children. She also learned Nahuatl, the Aztec language, and wrote poems in it.

In 1664, when she was 16, Inés moved to Mexico City. She even asked her mother if she could dress up as a boy to go to the university, but her mother said no. Since she couldn't get a formal education, Juana kept studying on her own.

Because her family was important, she became a lady-in-waiting at the court of the viceroy, who was like a governor for New Spain. The viceroy and his wife, Donna Eleonora del Carretto, were very impressed by her. The viceroy once tested her knowledge by inviting many smart people—theologians, lawyers, philosophers, and poets—to ask her questions. Juana answered them all without preparing, and everyone was amazed by how smart she was. Her writing skills made her famous throughout New Spain. She was admired at the court and received many marriage proposals, but she turned them all down.

Becoming a Nun and Her New Name

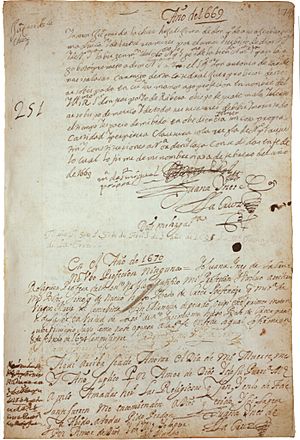

In 1667, Juana decided to become a nun. She first joined a strict group of nuns but left after a few months. In 1669, she joined the Hieronymite nuns, who had more relaxed rules. This is when she changed her name to Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. She chose to be a nun so she could study freely without other duties getting in the way. She wanted "to have no fixed occupation which might curtail my freedom to study."

Inside the convent, Sor Juana became good friends with another smart person, Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora. She lived in the Convent of Santa Paula in Mexico City from 1669 until she died in 1695. There, she studied, wrote, and built a huge library of books. The Viceroy and Vicereine of New Spain supported her and helped publish her writings in Spain. She even wrote some poems for her friend and supporter, María Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzága.

Challenges and Later Life

In 1690, a bishop named Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz published one of Sor Juana's writings without her permission. In this writing, called Carta Atenagórica, Sor Juana criticized a sermon given by another priest. The bishop also published his own letter, telling her to focus on religious studies instead of worldly ones. He agreed with her criticisms but believed that as a woman, she should pray and stop writing.

Sor Juana wrote a famous letter back, called Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz (Reply to Sister Philotea). In this letter, she bravely defended women's right to get an education. She also argued that women should be allowed to be intellectual leaders and have their writings published. She believed that older women could teach other women, which would also prevent problems with male teachers being alone with young female students. In 1691, she was told to stop writing after a private letter about women's education became public.

Sor Juana's strong opinions made her a controversial figure. She famously said, "One can perfectly well philosophize while cooking supper." This meant that women could be smart and think deeply even while doing everyday tasks. However, the Archbishop of Mexico and other church leaders criticized her for being "wayward." They also thought she should do more community work instead of just writing.

By 1693, it seemed she stopped writing to avoid more trouble with the church. Some documents show her agreeing to do penance. One document is signed "Yo, la Peor de Todas" ("I, the worst of all women"). It is said she sold all her books, which was a huge library of over 4,000 books, and her musical and scientific tools. Other stories say her books and instruments were taken from her because she challenged the Church.

Only a few of her many writings have survived. These are known as her Complete Works. It is believed that the vicereine helped save her writings.

Sor Juana died on April 17, 1695, after caring for other nuns who were sick with a plague. Her friend Sigüenza y Góngora gave a speech at her funeral.

Sor Juana's Works

Her Poetry

First Dream

First Dream is a long, philosophical poem. It describes a person falling asleep in the quiet night. All the animals are sleeping, and the person's body rests. Then, in a dream, the soul feels free and rises to the top of its own mind, like a pyramid aiming for God.

From this high point, the soul sees all of creation, but it's too much to understand at once. The soul's mind feels overwhelmed trying to grasp everything. So, reason steps in and tries to understand each part of creation one by one. The poem ends with the sun rising and the poet waking up.

Love Poems

Sor Juana's first book of poems, Inundación castálida, was published in Spain. Many of her poems were about love and feelings. Here is one of her sonnets:

| Soneto 173 | Sonnet 173 in Edith Grossman's 2014 translation |

|---|---|

|

Efectos muy penosos de amor, y que no por grandes se igualan con las prendas de quien le causa

¿Vesme, Alcino, que atada a la cadena |

The very distressing effects of love, but no matter how great, they do not equal the qualities of the one who causes them

Do you see me, Alcino, here am I caught |

Her Plays

Sor Juana also wrote plays. She used her comedies and humor to question the strict rules about how men and women should act. She showed how comedy often made women look bad to make men seem better. By using humor, she found a way to challenge these ideas in a way that was accepted at the time.

Pawns of a House

This play was first performed on October 4, 1683. It tells the story of two couples who are in love but face many challenges that keep them apart. This comedy is seen as one of the best plays from that time in Spanish-American literature. What makes it special is that a strong, determined woman drives the story. The main character, Dona Leonor, is a great example of this.

This play is often thought to be one of Sor Juana's best works. It is praised for its clever plot and how it shows the complicated relationships and changes in city life.

Love is but a Labyrinth

This play first opened on February 11, 1689. The story uses the well-known Greek myth of Theseus. Theseus is a hero from Crete Island who fights the Minotaur. He also wins the love of Ariadne and Phaedra. Sor Juana showed Theseus as a humble hero, not a proud one, even after his victory.

Her Music

Besides poetry and philosophy, Sor Juana was interested in science, math, and music. Music was very important to her. She spent a lot of time studying how musical instruments are tuned. She even wrote a book called El Caracol (which is now lost) that tried to make musical notation simpler.

In her writings, you can see how important sound was to her. She often wrote about musical notes and how they work. For example, in one poem, she talks about natural notes and accidentals in music.

One musical piece by Sor Juana still exists today. It is a four-part song called Madre, la de los primores.

Other Famous Works

Other well-known works by Sor Juana include Hombres Necios (Foolish Men) and The Divine Narcissus.

Her Impact on History

Helping Others

In 1993, an organization called Sor Juana Inés Services for Abused Women was started. It was created to continue Sor Juana's dedication to helping women who have experienced domestic violence. This group is now called Community Overcoming Relationship Abuse (CORA). It offers support services in Spanish to Latin American women and children facing domestic violence.

Education and Learning

The San Jerónimo Convent, where Sor Juana lived for 27 years and wrote most of her works, is now the University of the Cloister of Sor Juana. The Mexican government founded this university in 1979 in Mexico City.

Her Role in Feminism

Early Feminist Ideas

Sor Juana was part of a long discussion about women's roles that lasted for three centuries. This debate, called the Querelles des Femmes, focused on ideas about gender and how women were often treated unfairly.

Sor Juana's ideas and her connections with other women who supported women's rights greatly influenced her famous letter, La Respuesta. For women back then, talking with other women was just as important as writing. Sor Juana's strong stance in her writings challenged unfair treatment of women. She argued that ideas about women's roles in the church were made by people, not by God. This idea was very advanced for her time.

Modern Feminist Ideas

Today, people connect Sor Juana to modern feminist movements. These include religious feminism and ecofeminism (which links women's rights to protecting the environment).

Sor Juana criticized religious rules that only allowed men to be leaders in the Church. This shows her early religious feminism. She believed the Bible cared about all people and the Earth. She also worried about how Spanish rule was harming the planet. These ideas are similar to modern feminist movements that focus on decolonization and protecting the Earth.

Some scholars also connect Sor Juana to the modern lesbian movement and the Chicana movement. They see her as someone who questioned traditional ideas about relationships and supported the idea of a "lesbian continuum," which means a range of close bonds between women.

A Symbol for Mexico

Colonial and Indigenous Identities

As a religious woman, Sor Juana is linked to the Virgin of Guadalupe, a symbol of Mexican identity. She was also connected to Aztec goddesses. For example, parts of her poem Villancico 224 are written in Nahuatl, while others are in Spanish. The poem talks about both the Virgin of Guadalupe and Cihuacoatl, an Indigenous goddess. This shows her interest in blending Mexican and Indigenous religious ideas.

Sor Juana's play, Loa to Divine Narcissus, also shows her connection to Indigenous religious figures. The play features Indigenous characters and Spanish characters who discuss their religious beliefs. They find many similarities between their traditions. The play mentions Aztec rituals and gods, like Huitzilopochtli, who symbolized the land of Mexico.

Some scholars believe Sor Juana's mix of Spanish and Aztec traditions aimed to raise the status of Indigenous religions. She also highlighted the violence used by the Spanish to dominate Indigenous cultures. By using both colonial and Indigenous languages and symbols, Sor Juana gave a voice to marginalized Indigenous people and affirmed her own Indigenous identity.

Connection to Frida Kahlo

Some experts point out that women like Sor Juana and Frida Kahlo sometimes changed their appearance to challenge women's roles in society. Sor Juana cut her hair as a punishment for mistakes in her studies, which showed her independence. Nuns were also required to cut their hair when they entered the convent. These ideas are similar to Frida Kahlo's 1940 self-portrait, Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, where she shows herself with short hair.

The University of the Cloister of Sor Juana honored both Frida Kahlo and Sor Juana on October 31, 2018, with a special altar for the Day of the Dead. It was called Las Dos Juanas (The Two Juanas).

Official Recognition

Today, Sor Juana is still a very important figure in Mexico.

In April 1995, Sor Juana's name was written in gold on the wall of honor in the Mexican Congress. Her picture is also on the 200 pesos bill and was on the 1000 pesos coin. The town where she grew up, San Miguel Nepantla, was renamed Nepantla de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz in her honor.

Veneration

In 2022, the Episcopal Church of the United States officially added her to their calendar of saints. Her feast day is April 18.

Sor Juana in Popular Culture

Books and Poems

- American poet Diane Ackerman wrote a play in verse called Reverse Thunder about Sor Juana (1992).

- Canadian poet Margaret Atwood's 2007 book of poems The Door includes a poem titled "Sor Juana Works in the Garden."

- Puerto Rican poet Giannina Braschi wrote a novel called Yo-Yo Boing! where characters discuss the greatest women poets, including Sor Juana.

- Canadian novelist Paul Anderson spent 12 years writing a 1300-page novel about Sor Juana called Hunger's Brides (2004).

Music

- American composer John Adams used two of Sor Juana's poems in his musical work El Niño (2000).

- Composer Allison Sniffin created a piece called Óyeme con los ojos (Hear Me with Your Eyes: Sor Juana on the Nature of Love), using Sor Juana's words.

- Composers Daniel Crozier and Peter M. Krask wrote an opera about her life called With Blood, With Ink.

- Puerto Rican singer iLe recites part of one of Sor Juana's sonnets in her song "Rescatarme."

- In 2013, Brazilian composer Jorge Antunes created an electronic music piece called CARTA ATHENAGÓRICA to honor Sor Juana.

Movies and TV Shows

- A telenovela (TV soap opera) about her life, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, was made in 1962.

- María Luisa Bemberg wrote and directed the 1990 film Yo, la peor de todas (I, the Worst of All), which is based on Sor Juana's life.

- The Spanish-language TV miniseries Juana Inés (2016) shows her life story.

Theater Plays

- Helen Edmundson's play The Heresy of Love, based on Sor Juana's life, was first performed in 2012.

- Playwright Kenneth Prestininzi wrote Impure Thoughts (Without Apology) about Sor Juana's experiences with Bishop Francisco Aguilar y Seijas.

- Tanya Saracho's play The Tenth Muse is a fictional story about women in a convent in Colonial Mexico who discover Sor Juana's writings.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Juana Inés de la Cruz para niños

In Spanish: Juana Inés de la Cruz para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |