Southampton town walls facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Southampton town walls |

|

|---|---|

| Hampshire, England | |

Southampton town walls

|

|

| Coordinates | 50°54′03″N 1°24′19″W / 50.9007°N 1.4054°W |

| Type | City walls |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Approximately half the medieval circuit remains intact |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Stone |

| Battles/wars | French raid of 1338 |

The Southampton town walls are old defensive structures built around the town of Southampton in southern England. Long ago, even before these walls, Roman and Anglo-Saxon settlements in the area had their own ways to protect themselves, like ditches or early walls. The walls we see today started when the town moved to its current spot in the 10th century. Back then, the town was protected by earth banks, ditches, and the natural shape of the river and coastline.

The Normans, who came after, built a castle in Southampton. But they didn't really improve the town's wider defences until the early 1200s. Southampton was becoming a busy trading port, and there were often fights with France. This led to the building of stone walls and gatehouses on the north and east sides of the town.

In 1338, French forces attacked Southampton. The town's defences weren't strong enough, especially along the quays (docks) on the west and south sides. King Edward III quickly ordered improvements. But it wasn't until the 1360s that major building work began. Over the next few decades, the town was completely surrounded by a 2-kilometer (1.25-mile) stone wall. This wall had 29 towers and eight gates. When gunpowder weapons became available in the 1360s and 1370s, Southampton was one of the first English towns to add this new technology to its walls. They even built new towers just for cannons.

Southampton's town walls were very important for defence during the 1400s. The gatehouses were also used for important town activities. For example, some acted as the town's guildhall (a meeting place for town leaders) or held the town's gaol (a place for holding people). After the late 1600s, the walls became less important. Over the 1700s and 1800s, parts of the walls were taken down or changed for other uses. This continued into the early 1900s. But after World War II, people realized how historically important the walls were. Now, projects work to protect them, and they are a popular tourist attraction.

Contents

History of Southampton's Walls

Early Defences: 1st to 10th Centuries

Before modern Southampton, other settlements nearby had protective walls. After the Roman conquest of Britain in AD 43, the Romans built a fort called Clausentum. It was an important trading port and a defence point for Winchester. Clausentum had a flint stone wall and two ditches on its land side.

Later, in the 7th and 8th centuries, the Anglo-Saxons built a planned town called Hamwic. This was close to where Southampton is now. Parts of Hamwic had a ditch around it, about 3 meters (10 feet) wide and 1.5 meters (5 feet) deep. It might also have had an earth bank. In the 10th century, Vikings often raided the area. This led the people of Southampton to move their settlement to its current, safer location.

Building Stone Walls: 11th to 13th Centuries

By the time the Normans took over England in 1066, Southampton was a town overlooking the River Test. Water protected most sides, and ditches and banks protected the north and east. The Normans built a castle inside the town. This caused some damage to nearby buildings as space was cleared for the new fort.

Later, in the 1100s, King Henry II improved the castle. Southampton became more important for coastal defence and for military actions in Europe. But no major work was done on the town's ditches and banks yet.

By the 12th century, Southampton was a busy trading port. It had trade routes to France, the Middle East, and Gascony. The town and castle helped with this trade. Wealthy merchants started building stone houses, especially in the western and southern parts of town. But these houses were not easy to defend.

The English Channel was a battleground between England and France in the 1200s. Southampton was a key naval base and a tempting target for raiders. So, in the early 1200s, work began to improve the town's defences. The king gave money in 1202 and 1203 to help build up the earth banks. By 1217, the East Gate was built, probably of stone.

In 1260, King Edward I gave Southampton a "murage grant." This allowed the town to tax certain imported goods to pay for new stone walls. These grants helped turn many of the earth banks in the north and east into stone walls. However, there wasn't much effort to defend the west and south quays. This was probably because walls there would have made it harder for merchants to move their goods.

French Attacks and New Defences: 14th Century

By 1300, Southampton was a major port with about 5,000 people. More murage grants were given in 1321. These might have paid for the stone towers of the Bargate and some round wall towers. Some stone walling also started in the south and west. But later, it was found that some of this money was not used properly. This led to weak defences and large gaps in the walls.

In 1338, French forces successfully attacked Southampton. The town's defences, especially in the west, were very poor. The French burned many buildings, particularly along the western quays, and damaged the castle. King Edward III quickly ordered improvements and told the town to build stone walls all around. In 1339, workers were brought in to improve the defences. Money was raised by changing a prison sentence for a town official into a fine. Murage grants were given again in 1345. But the French raids had badly hurt Southampton's economy, and the town never fully recovered. The king's order to fully enclose the town with walls could not be completed right away. Still, by the 1350s, Southampton had mangonel and springald siege engines mounted on its existing walls.

In 1360, the king looked into Southampton's defences. In 1363, he set up a group to figure out the best way to improve them. They decided that the town walls needed better care and should be kept clear of buildings. They also said that there should be fewer gates in the walls. A water-filled ditch should be built to make the western walls stronger. Also, the ground-floor windows and outer doors of properties facing the sea should be filled in to create a stronger defence line.

The work that followed greatly improved Southampton's defences. By the late 1300s, the town was completely surrounded by 2 kilometers (1.25 miles) of stone walls. Some existing buildings, like a dovecote (a pigeon house), were made stronger and used as part of the defences. The South Gate was built to protect the southern quays. It had a wide archway with parapets (low protective walls) and machicolations (openings for dropping things on attackers). This building work was very expensive. Even though the mayor and town officials made citizens help, Parliament had to be asked several times in the 1370s to help by forgiving taxes owed by Southampton.

In 1370, the French attacked Portsmouth, starting more raids along the English coast. King Edward, and then King Richard II, improved defences in southern England. This included fixing Southampton Castle, which was in poor condition partly because town citizens had stolen building materials. Henry Yevele, who oversaw castle improvements, probably also built the Arcades along the western walls in 1380. This involved blocking up properties along the western quay to form a solid wall and adding three towers and gunports. Sir John Sondes and John Polymond were appointed in 1386 to further improve the town walls. Polymond and Arundel Towers were likely named after these men.

A big change from the 1370s was adapting the walls for gunpowder weapons. Cannons were new and not very reliable yet. They could only shoot short distances and needed special gunports. Cannons fired stone balls, which didn't do much damage to strong stone walls. So, they were mainly used for defence, not for attacking. The first gunports in Britain were built in the 1360s on the Isle of Wight, and Southampton quickly followed. Around 1378-1379, gunports for handguns were built into the western Arcade wall. By 1382, the town bought its own gun. God's House Tower was built around 1417 to defend the southern quays and control the town's moats. It had many gunports and rooftop firing points. By 1439, Catchcold tower was also built for gunpowder weapons.

Another change in the 1370s was making the process of guarding and maintaining the walls more formal. In 1377, King Edward told the mayor to check these processes. It seems the town was divided into four areas, and each property was given a section of the wall to maintain. The size of the section depended on the size of the property. The four areas were also in charge of security and policing the town.

Walls in Later Centuries: 15th to 20th Centuries

The threat of French attack continued through the 15th century. Instead of murage grants, the king directly gave more money for the walls, including £100 annually from 1400. Concerns grew after a French attack on Sandwich in 1457. The same year, guns on Southampton's walls fired at French raiding ships. The walls were maintained for the rest of the century. In contrast, the castle quickly fell apart and was used for rubbish and small farms.

Around 1460, a report said that the north and east walls were too thin to stop a cannon shot or for a person to stand on them. A wooden and earth walkway had been built behind the walls, but it was expensive to keep up. Modern studies confirm that parts of the eastern wall were only 0.76 meters (2.49 feet) thick. Other English town walls were usually about 1 meter (3.28 feet) thick.

A 1454 survey showed that the system from 1377 for maintaining the walls was still in use. By the 15th century, the town had a gunner, who earned the highest salary of any local official. He was in charge of maintaining the guns and making gunpowder. Even in the mid-1500s, new, improved gunports were added to the West Gate.

Several gatehouses were important for running the town in the 15th century. The South Gate was the main office for the port. It housed the Clerk of the King's Ships and collected customs taxes. It was expanded in the 1430s and 1440s. The Bargate was partly used as a prison from the 15th century. The first floor of the Bargate had been the town's guildhall since at least 1441. The town's money was kept in one of its towers.

Decline and Preservation: 17th to 20th Centuries

The town walls became less important for defence in the 17th century. In 1633, a footpath was built inside the wall for the watch to catch criminals. The walls lasted longer than Southampton Castle, which was sold in 1618. The walls were not used in the English Civil War. Some stone from the castle was even used to strengthen the town walls in 1650 during the Third English Civil War.

From the 18th century onwards, parts of the walls were changed or simply torn down. By 1707, part of God's House Tower was used as a prison. From 1786, it became the official town gaol. As the century went on, the East Gate was torn down in 1774. The South Gate was mostly demolished in 1803, and Biddles Gate soon after, along with large sections of the wall.

In the 19th century, the destruction and changes to the walls continued. The top parts of Polymond Tower were torn down in the 1820s. They were rebuilt by 1846 as a shorter, two-story tower. The remains of the South Gate became a hotel. God's House Tower continued as a gaol, but inspectors criticized it. An 1823 report called it "old and very awkward," with about a dozen prisoners in damp conditions. In 1855, it stopped being a gaol and was no longer used.

Other improvements were made. In 1853, the "Forty Steps" were built down the west walls to make it easier to get into town. Parts of the Arcades were blocked up to stop homeless people from sleeping there. The Bargate stopped being the guildhall in 1888. It was then heavily restored to look more like it did in medieval times.

As Southampton grew, like many walled towns, the old fortifications faced pressure. In 1898-1899, parts of the wall west of Biddles Gate were torn down to create the Western Esplanade road. By the second half of the century, the Bargate and nearby walls caused serious traffic jams. People thought about tearing them down. But in the 1930s, it was decided to keep the gatehouse but tear down the walls on either side.

Some parts of the Southampton walls were used for searchlights and machineguns during the Second World War. The walls were not damaged, unlike many other parts of the medieval city. After the war, people recognized the historical importance of the walls. A lot of work has been done to preserve them, including undoing the Victorian changes to the Arcades. The town walls are now seen as an important part of Southampton's tourist industry. However, for safety reasons, tourists cannot walk along most of the walls. God's House Tower reopened in 1961 as Southampton's Museum of Archaeology. Today, the walls are protected as grade I listed buildings and as a scheduled monument.

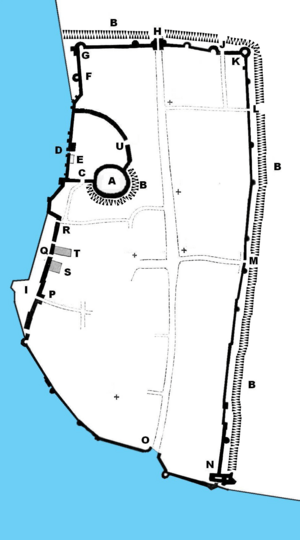

Architecture of the Walls

About half of the 2-kilometer (1.25-mile) long medieval town walls still stand today. Most of what remains is on the north and west sides of Southampton. Thirteen of the original 29 defensive towers and six of the eight gates are also still there. The towers are a mix of round and square designs. Many have an "open-gorged" design, similar to those in North Wales. This meant they could be cut off from the rest of the walls by removing small wooden bridges. Overall, the town walls at Southampton were built over many years and sometimes in a messy way. However, the remaining gatehouses are well-designed and complex, probably because they were so important to the town. Experts Oliver Creighton and Robert Higham say the remaining walls are "extremely well preserved" and have "unique survivals in a British context."

In the south-east corner of the walls is God's House Tower. This building is important because it was one of the first town buildings designed to hold gunpowder artillery. In this way, it is very similar to Cow Tower in Norwich. The tower was built next to God's House Gate and is three stories high. You can see the gunports for hand-cannons on the outside. The roof was designed to hold larger cannons. Next to the tower is God's House Gate, a two-story building also with a gunport.

Little remains of the eastern walls. But in the north-east corner, several towers are still mostly complete. These include Polymond Tower, a strong round tower largely rebuilt in the Victorian period. Further west is the Bargate. This was first a simple archway. It was then expanded with round towers and arrow slits in the early 1300s. In the early 1400s, it was expanded again with battlements and parapets. It was heavily restored in the 1800s. The Bargate is still a detailed building, mixing military symbols with rich town heraldry and decorations above the gateway.

At the north-west corner of the walls is Arundel Tower, another large round tower that once looked over a small cliff. South of this is Catchcold Tower. Catchcold Tower was designed for guns and has three gunports. The need to support cannons makes it look much heavier than the other round towers on the walls. You can still see the remains of machine gun mounts added to the tower in 1941. The Arcades are part of the remaining west walls and are unique in England. Their closest architectural match is in Rouen, France. The West Gate is still three stories high and was originally protected by two portcullises (heavy grilles that could be lowered). The windows on the west side of the gate are the original medieval designs. Along the south side of the walls, one of the two towers protecting the South Gate still stands, mostly complete.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |