Spanish colonization attempt of the Strait of Magellan facts for kids

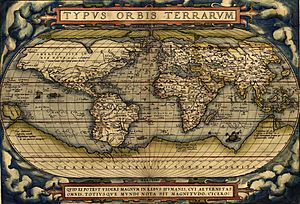

In the late 1500s, the Spanish Empire tried to build settlements in the Strait of Magellan. This was a very important waterway. Spain wanted to control it because it was the only known way to sail between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans at that time.

This plan started because of Francis Drake. In 1578, Drake, an English explorer, sailed through the strait. His men then caused a lot of trouble along the Pacific coast of Spanish America. To stop this from happening again, Spain sent a naval expedition. It was led by an experienced explorer named Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa. The expedition left Cádiz, Spain, in December 1581.

They built two settlements in the strait: Nombre de Jesús and Ciudad del Rey Don Felipe. But these settlements did not last long. The settlers were not ready for the cold and windy weather of the strait. Soon, many people were starving and getting sick.

Sarmiento tried to send more supplies from Río de Janeiro in 1585. But bad weather stopped his ships from reaching the strait. Later, Sarmiento was captured by English pirates in 1586. This made it even harder to send help. King Philip II of Spain also did not send much help. This was probably because Spain was busy fighting wars with England and Dutch rebels. The last known survivor from the settlements was rescued by a passing ship in 1590.

Later, explorers found other ways to sail around Tierra del Fuego, south of the Strait of Magellan. Once these new routes were known, Spain gave up its plans to settle the strait.

Contents

Why Spain Wanted the Strait

In the 1500s, people had different ideas about the Strait of Magellan. Some, like Antonio Pigafetta, who sailed with Magellan, thought it was too hard to use often. But others saw it as a great chance for trade and a very important place.

Pigafetta had described the strait as a good place. He said it had many safe ports, "cedar" wood, and lots of shellfish and fish. A Spanish leader named Pedro de Valdivia first worried about the strait. He feared rival explorers might use it to challenge his control in Chile. Later, when he was more powerful, he wanted to use the strait to connect his colony directly to Seville, Spain.

Valdivia sent two sea trips from Chile to explore the strait. Juan Bautista Pastene went in 1544, and Francisco de Ulloa in 1553–1554. In 1552, Valdivia also sent Francisco de Villagra to try to reach the strait by land. Villagra crossed the Andes mountains but only got as far as the Limay River. Valdivia's successor, García Hurtado de Mendoza, sent another sea trip led by Juan Ladrillero in 1557–1558.

Spanish settlements in South America never reached the Strait of Magellan by land. Their expansion south stopped after they took over the Chiloé Archipelago in 1567. Spain likely did not have strong reasons to conquer more land further south. The native people there were few and did not live in settled farming communities like the Spanish.

For a long time, Spain considered the Pacific Ocean a Mare clausum. This means a "closed sea" to other countries. But in 1578, the English sailor Francis Drake entered the Pacific through the strait. This started a time of privateering and piracy along the coasts of Chile. News of Drake's actions made people in Spanish settlements on the Pacific coast very worried.

To deal with this new threat, the Viceroy of Peru, Francisco de Toledo, sent two ships. They were led by Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa. Their job was to explore the strait and see if it could be fortified. This would help Spain control the entrance to the Pacific Ocean from the Atlantic. Sarmiento's trip explored the strait, looking for English invaders. They also mapped places for future forts.

The Attempt to Settle

After exploring the strait, Sarmiento went to Spain. There, he got ships and settlers from the King for a big project. The plan was to build forts and settlements. The Duke of Alba supported the plan. He suggested building a fort on each side of Primera Angostura, a narrow part of the strait. An Italian military engineer, Giovanni Battista Antonelli, helped design the forts. However, the Primera Angostura location was later changed. This was because the tides there would help ships get through the narrow passage. The expedition that sailed from Spain included about 350 settlers and 400 soldiers.

Back in the Strait of Magellan, Sarmiento founded the city of Nombre de Jesús. It was at the Atlantic entrance of the strait, founded on February 11. On the night of February 17, some officials secretly left the expedition. They took the three best ships and most of the supplies.

Sarmiento left Antonio de Biedma in charge of Nombre de Jesús. Sarmiento then walked along the northern shore of the strait with a group. On March 23, Sarmiento's group found a bay with good conditions. Two days later, they founded the city of Ciudad del Rey Don Felipe there. Ciudad del Rey Don Felipe was built with many wooden buildings. These included a church, a town hall, a royal storage house, a Franciscan convent, and a clergy house.

The settlers were not well-prepared. Most of them were from Andalusia, a region in Spain. Its Mediterranean climate was very different from the windy Patagonia. The settlements were supposed to grow their own food. But the plants the Spanish brought were hard to grow. Instead, the settlers mostly ate shellfish and canelo ("cinnamon") bark.

Nombre de Jesús was abandoned after only five months. Its people moved to Ciudad del Rey Don Felipe. There, they realized there was not enough food for everyone. Andrés de Biedma told the people to spread out along the northern coast of the strait. They were to wait for any ship that could bring help. Sarmiento's supply expedition never reached the strait because of a storm.

In the winter of 1584, many settlers were starving and sick. Biedma tried to evacuate some people in two small ships they built. But the attempt failed when one ship sank near Cape San Isidro. This was about 20 kilometers south of Ciudad Rey Don Felipe. Biedma kept very strict rules among the settlers, and many died.

When the next English sailor, Thomas Cavendish, landed at Ciudad Rey Don Felipe in 1587, he found the settlement in ruins. He also found a few survivors, but he refused to help them. He took six cannons from the settlement. He then renamed the place "Port Famine."

The last known survivor was rescued in 1590. This was by Andrew Merrick, captain of the Delight. This was the only ship out of five that reached the strait from an expedition led by another English privateer, John Childley.

Why the Settlements Failed

Cavendish thought Ciudad Rey Don Felipe was in the "best place of the strait." In 1837, a French expedition led by Jules Dumont d'Urville explored the area. Dumont correctly guessed where Ciudad Rey Don Felipe was. He noted its good natural location.

Many settlers died due to disease, harsh conditions, and conflicts. Diseases were especially common among the settlers. A big reason for the failure and deaths was the low morale of the settlers from the very beginning. This bad mood was partly due to many problems the expedition faced. These problems happened between leaving Spain and arriving at the strait.

King Philip II did not send help, even though Sarmiento asked him many times. This was likely because Spain's money and resources were stretched thin. They were fighting wars with England and Dutch rebels.

Historian Mateo Martinic called this settlement attempt "the most unfortunate chapter of human history in the Strait of Magellan."

What Happened Next

Ideas to settle the strait came up again in Spain in 1671. This was because of John Narborough's expedition to Chile. Rumors of a foreign settlement in Patagonia came up again in 1676. Claims reached Spain that England was planning to settle the Strait of Magellan. Another idea to settle the strait was suggested in 1702. This was by the Governor of Chile Francisco Ibáñez de Peralta. He said the Captaincy General of Chile would pay for it if they received their payments on time. However, Spain's failure to settle the Strait of Magellan in the 1580s was so well-known. It stopped any new attempts to settle the strait for hundreds of years.

Because the strait was not settled, the Chiloé Archipelago became very important. It helped protect western Patagonia from foreign ships. The city of Valdivia, which was rebuilt in 1645, and Chiloé acted like guards. They were also places where Spain gathered information from all over Patagonia.

See also

In Spanish: Intento de colonizaci%C3%B3n espa%C3%B1ola del estrecho de Magallanes para ni%C3%B1os

In Spanish: Intento de colonizaci%C3%B3n espa%C3%B1ola del estrecho de Magallanes para ni%C3%B1os

- Antonio de Vea expedition

- Chilean colonization of the Strait of Magellan

- Coastal defence of colonial Chile

- Coastal fortifications of colonial Chile

- García de Nodal expedition

Sources