Funj Sultanate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Blue Sultanate / Funj Sultanate

السلطنة الزرقاء

As-Saltana az-Zarqa |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1504–1821 | |||||||||

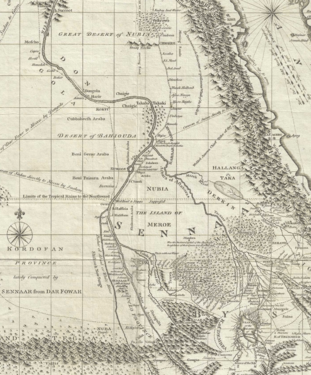

The Funj Sultanate at its peak in around 1700

|

|||||||||

| Status | Confederation of sultanates and dependent tribal emirates under Sennar's suzerainty | ||||||||

| Capital | Sennar | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic (official language, lingua franca and language of Islam, increasingly spoken language) Nubian languages (native tongue, increasingly replaced by Arabic) |

||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam, Coptic Christianity |

||||||||

| Government | Islamic Monarchy | ||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||

|

• 1504–1533/4

|

Amara Dunqas (first) | ||||||||

|

• 1805–1821

|

Badi VII (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Great Council Shura | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||

|

• Established

|

1504 | ||||||||

|

• Conquered by Egypt

|

14 June 1821 | ||||||||

|

• Annexed to Egypt Province, Ottoman Empire

|

13 February 1841 | ||||||||

| Currency | barter | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | Sudan Eritrea Ethiopia |

||||||||

|

a. Muhammad Ali of Egypt was granted the non-hereditary governorship of Sudan by an 1841 Ottoman firman.

b. Estimate for entire area covered by modern Sudan. c. The Funj mostly did not mint coins and the markets rarely used coinage as a form of exchange. Coinage didn't become widespread in cities until the 18th century. French surgeon J. C. Poncet, who visited Sennar in 1699, mentions the use of foreign coins such as Spanish reals. |

|||||||||

The Funj Sultanate, also known as Funjistan, Sultanate of Sennar (named after its capital Sennar) or Blue Sultanate, was a kingdom in parts of what is now Sudan, northwestern Eritrea, and western Ethiopia. It was founded in 1504 by the Funj people.

The Funj Sultanate quickly adopted Islam, but at first, this was mostly for show. The state was more of an "African empire with a Muslim façade" until a stricter form of Islam became common in the 18th century. The sultanate was strongest in the late 17th century. However, its power slowly faded in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1821, the last sultan, who had lost much of his power, gave up without a fight to the Ottoman Egyptian invasion.

Contents

History of the Funj Sultanate

How the Funj Sultanate Began

The Christian kingdoms of Nubia, like Makuria and Alodia, started to weaken around the 12th century. By 1365, Makuria had almost disappeared. The fate of Alodia is less clear, but it also likely fell apart around the 12th or 13th century.

By the 13th century, central Sudan was divided into many small states. Between the 14th and 15th centuries, Bedouin tribes moved into Sudan. One of these tribes, led by Abdallah Jammah, formed a group of tribes. He then destroyed what was left of Alodia. In the early 16th century, Abdallah's group was attacked by invaders from the south, known as the Funj.

Historians still debate where the Funj people came from. Some think they were Nubians or Shilluk. Others believe "Funj" was not an ethnic group but a social class.

In 1504, the Funj defeated Abdallah Jammah and established the Funj Sultanate.

Challenges from Ottomans and Local Rebellions

In 1523, a Jewish traveler named David Reubeni visited the kingdom. He wrote that Sultan Amara Dunqas traveled a lot. The sultan ruled over both "black people and white" from the Nile's meeting point south to Dongola. He had many animals and horsemen.

Two years later, Ottoman admiral Selman Reis called the Funj kingdom weak. He said it could be easily conquered. He also mentioned that Amara paid a yearly tribute of 9,000 camels to the Ethiopian Empire. The Ottomans took over Sawakin in 1526, which was linked to Sennar. The Funj likely allied with Ethiopia to stop the Ottoman expansion in the Red Sea area.

The Ottomans tried to conquer the Funj in 1555 but failed. By 1570, they had settled in Lower Nubia. They pushed south to the third Nile cataract. In 1585, the Funj defeated the Ottomans at the battle of Hannik. This battlefield became the border between the two kingdoms. By the late 16th century, the Funj expanded into northwestern Eritrea. The Ottomans stopped trying to expand, and the Funj-Ethiopian alliance was no longer needed.

Meanwhile, a local king named Ajib grew powerful in northern Nubia. He forced Sultan Tayyib to marry his daughter. This made Tayyib and his successor, Unsa, Ajib's puppets. Unsa was removed from power in 1603/1604. This led Ajib to invade the Funj heartland. His armies pushed the Funj king southeast. Ajib then ruled an area from Dongola to Ethiopia.

The new Funj sultan, Adlan I, fought back. He killed Ajib in 1611 or 1612. Adlan II was later removed from power. Badi I became sultan. He made a peace treaty with Ajib's sons. The Funj state was split. Ajib's successors, the Abdallab, ruled everything north of the Blue and White Nile meeting point. They were vassals of Sennar. This meant the Funj lost direct control over much of their kingdom.

The Funj Sultanate's Strongest Period

The Funj sultans faced challenges from the Ethiopian emperor. In 1617, Emperor Susenyos raided Funj provinces. This led to a full-scale war in 1618 and 1619. Many eastern Funj provinces were destroyed. After the war, the two countries remained peaceful for over a century.

Sultan Rabat I ruled during this war. He was the first of three rulers who led the sultanate into a time of growth and prosperity. During this period, the Funj had more contact with other countries.

In the 17th century, the Shilluk and Sennar formed an alliance. They worked together against the growing power of the Dinka. After this alliance ended in 1650, Sultan Badi II took over the northern part of the Shilluk Kingdom. Under his rule, the Funj also defeated the Kingdom of Taqali to the west. Its ruler became a vassal of the Funj.

Decline of the Sultanate

Sennar was at its strongest at the end of the 17th century. However, in the 18th century, the power of the sultan began to weaken. The biggest challenge came from wealthy merchants and religious scholars called Ulama. They believed it was their right to decide on justice.

Around 1718, the ruling family was overthrown. Nul became sultan. He was related to the old family but started his own dynasty.

In 1741 and 1743, the young Ethiopian emperor Iyasu II led raids to gain military fame. In March 1744, he gathered a large army for a new expedition. This turned into a war of conquest. The two states fought a major battle at the Dinder river. Sennar won this battle. Sultan Badi IV became a national hero for stopping the Ethiopian invasion. Hostilities continued until 1755.

Badi IV's victory over the Ethiopians may have made him stronger. He had his chief minister executed and took full control. He tried to create a new power base. He took land from the nobles and gave power to new people from the western and southern parts of his kingdom. One of these people was Muhammad Abu Likayik. He was a cavalry commander. He was sent to control Kordofan, which was a battleground between the Funj and the Musabb’at.

Abu Likayik took over Kordofan in 1755. Sultan Badi became very unpopular because of his harsh rules. Disgruntled nobles convinced Abu Likayik to march on the capital. He reached Alays in 1760/1761. There, Badi was officially removed from power. Abu Likayik then attacked Sennar and entered it on March 27, 1762. Badi fled to Ethiopia but was killed in 1763. This began the Hamaj Regency, where the Funj sultans became puppets of the Hamaj.

Abu Likayik put another member of the royal family on the throne as a puppet sultan. He ruled as regent. This started a long conflict. The Funj sultans tried to regain their power. The Hamaj regents tried to keep control. These internal fights greatly weakened the state. In the late 18th century, Mek Adlan II took power. During this time, the Turks started to establish a presence in the Funj kingdom. The Turkish ruler, Al-Tahir Agha, married Khadeeja, daughter of Mek Adlan II. This helped the Funj become part of the Ottoman Empire.

The Funj state quickly fell apart in the late 18th century. In 1785/6, the Fur Sultanate conquered Kordofan. Sennar lost the Tigre region in Eritrea. After 1791, Taka around the Sudanese Mareb River became independent. The Shukriya became powerful in the Butana region. Dongola fell to the Shaiqiya around 1782. After 1802, the sultanate's power was limited to the Gezira area.

In the early 19th century, the kingdom suffered from many civil wars. Regent Muhammad Adlan, who came to power in 1808, stopped these wars. He stabilized the kingdom for another 13 years.

In 1820, Ismail bin Muhammad Ali, a general and son of Muhammad Ali Pasha, began conquering Sudan. Muhammad Adlan planned to fight back. But he was killed near Sennar in early 1821. One of the killers, Daf'Allah, went to the capital. He prepared Sultan Badi VII's surrender ceremony to the Turks. The Turks reached the Nile in May 1821. They traveled up the Blue Nile to Sennar. They were disappointed to find Sennar in ruins. On June 14, Badi VII officially surrendered.

Government and Rule

How the Sultanate was Run

The sultans of Sennar were powerful, but they did not have absolute power. A council of 20 elders also helped make state decisions. Below the king was the chief minister, called the amin. The jundi oversaw the market and led the state police. Another important official was the sid al-qum. He was a royal bodyguard and executioner. He was the only one allowed to kill royal family members. His job was to kill all brothers of a new king to prevent civil wars.

The state was divided into several provinces. Each province was led by a manjil. These provinces were then divided into smaller areas. Each small area was governed by a makk. The makk reported to their manjil. The most important manjil was from the Abdallabs.

The king of Sennar kept control over the manjils. He made them marry women from the royal family. These women acted as royal spies. A royal family member also sat with each manjil to watch their actions. Also, manjils had to visit Sennar every year. They paid tribute and reported on their work.

Sennar became the permanent capital under King Badi II. Written documents about how the state was run started to appear then. The oldest known document is from 1654.

The Funj Military

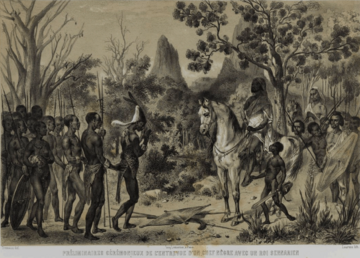

The Funj army was organized in a feudal way. This means that noble families provided military units. The strength of a unit was measured by its horsemen. Ordinary people were rarely called to fight, only in extreme emergencies. Most Funj warriors were people captured in yearly raids. These raids targeted non-Muslim people in the Nuba mountains.

The army had infantry (foot soldiers) and cavalry (horsemen). The Sultan rarely led armies himself. Instead, he appointed a commander for each campaign. Nomadic warriors fighting for the Funj had their own leader.

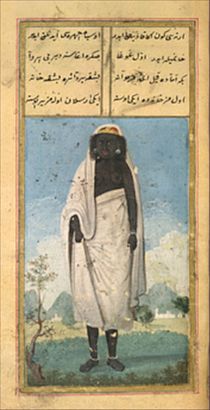

Funj warriors used lances for thrusting. They also had throwing knives and javelins. For defense, they used hide shields. Their most important weapon was a long broadsword that could be used with two hands. Warriors wore leather or quilted armor. They also had mail armor and leather gloves. Iron or copper helmets protected their heads. Horses also wore armor, including thick quilts and copper headgear.

Armor was made locally and sometimes imported. In the late 17th century, Sultan Badi III tried to modernize the army. He imported firearms and even cannons. But these were quickly abandoned after his death. They were expensive and unreliable. Also, the traditional armed elites feared losing their power. In the early 1770s, a traveler noted that the Sultan had "not one musket in his whole army."

Later, in 1820, some groups like the Shaiqiya had a few pistols and guns. But most still used traditional weapons. The Funj also used Shilluk and Dinka mercenaries (paid soldiers).

Culture and Society

Religion in the Sultanate

Islam

By 1523, the Funj had converted to Islam. They were originally Pagans or a mix of Christian and traditional beliefs. They likely converted to make it easier to rule their Muslim subjects. It also helped with trade with countries like Egypt. However, their adoption of Islam was not very strict at first. The Funj Sultanate even kept some African sacred traditions strong.

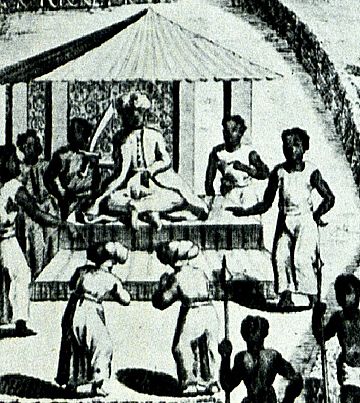

The Funj monarchy was considered divine. The Sultan had many wives. He spent most of his time inside the palace, away from his people. He only met with a few officials. He was not allowed to be seen eating. When he appeared in public, he wore a veil and was surrounded by great ceremony. The Sultan was regularly judged. If he was found to be failing, he could be executed.

People believed that all Funj, especially the Sultan, could detect magic. Islamic charms written in Sennar were thought to have special powers because they were near the Sultan. Among the common people, even the basics of Islam were not widely known. Pork and beer were common foods. When an important person died, people mourned by "communal dancing and rolling in the ashes of the feast-fire." In some areas, elderly or sick people who felt they were a burden would ask to be buried alive. As late as the late 17th century, the Funj Sultanate was still not following the "laws of the Turks" (meaning Islam). So, until the 18th century, Islam was mostly just a public image.

Despite this, the Funj supported Islam from the beginning. They encouraged Muslim holy men to settle in their lands. Later, civil wars forced farmers to seek protection from these holy men. This caused the sultans to lose influence over the farming population to the Ulama (religious scholars).

Christianity

When the Christian Nubian states fell, Christian institutions also collapsed. However, the Christian faith continued to exist, though it slowly declined. By the 16th century, many people in Nubia were still Christian. Dongola, a former Christian center, was mostly Islamized by the early 16th century. But a letter from 1742 confirms a Christian community south of Dongola.

In 1699, a traveler noted that Muslims in Sennar would say a Muslim prayer when they met Christians. The Fazughli region might have been Christian for a generation after its conquest in 1685. A Christian area was mentioned there as late as 1773. The Tigre in northwestern Eritrea remained Christian until the 19th century. Some rituals from Christian traditions continued even after people converted to Islam, lasting until the 20th century.

From the 17th century, foreign Christian groups were present in Sennar. These included Copts, Ethiopians, Greeks, Armenians, and Portuguese merchants. The sultanate was also a stop for Ethiopian Christians traveling to Egypt and the Holy Land. European missionaries traveling to Ethiopia also passed through Sennar.

Languages Spoken

In the Christian period, Nubian languages were spoken from Aswan in the north to south of the Blue and White Nile meeting point. These languages remained important during the Funj period. But they were slowly replaced by Arabic. This process was completed in central Sudan by the 19th century.

After the Funj converted to Islam, Arabic became the main language for government and trade. It was also the language of religion. The royal court continued to speak their old language for some time. But by around 1700, Arabic was the language used at court. In the 18th century, Arabic became the written language for state administration. As late as 1821, when the kingdom fell, some provincial nobles still could not speak Arabic.

Travelers in the 17th and 19th centuries described a pre-Arabic language in the Funj heartland. One traveler noted a "Fungi" language that sounded like Nubian. It had many Arabic words. This language was spoken as far north as Khartoum, but Arabic was more common. In Kordofan, Nubian was still spoken as a main or secondary language in the 1820s and 1830s.

Trade and Economy

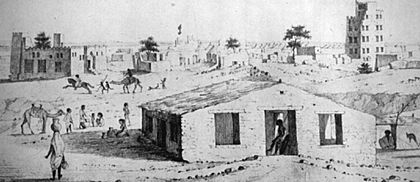

During the late 17th and early 18th century, under Sultan Badi III, the capital city of Sennar was a busy and diverse place. It was described as "close to being the greatest trading city" in all of Africa. The wealth and power of the sultans came from their control of the economy.

The monarch controlled all trade caravans. They also controlled the gold supply, which was the main form of money. Important income came from taxes on goods traveling along trade routes to Egypt and Red Sea ports. Taxes were also collected from people making pilgrimages from Western Sudan. In the late 17th century, the Funj started trading with the Ottoman Empire.

With the introduction of coins in the late 17th century, a less regulated market system developed. The sultans lost control of the market to a new class of wealthy merchants. Foreign money became widely used by merchants. This weakened the monarch's power to control the economy closely. The thriving trade created a rich class of educated merchants. They read a lot about Islam and became concerned about the lack of strict Islamic practices in the kingdom.

The Sultanate also tried to control the slave trade to Egypt. This was mainly done through a yearly caravan of up to one thousand enslaved people. This control was most successful in the 17th century. It still worked to some extent in the 18th century.

Rulers

The rulers of Sennar held the title of Mek (sultan). Their regnal numbers vary from source to source.

- Amara Dunqas 1503-1533/4 (AH 940)

- Nayil 1533/4 (AH 940)-1550/1 (AH 957)

- Abd al-Qadir I 1550/1 (AH 957)-1557/8 (AH 965)

- Abu Sakikin 1557/8 (AH 965)-1568

- Dakin 1568-1585/6 (AH 994)

- Dawra 1585/6 (AH 994)-1587/8 (AH 996)

- Tayyib 1587/8 (AH 996)-1591

- Unsa I 1591-1603/4 (AH 1012)

- Abd al-Qadir II 1603/4 (AH 1012)-1606

- Adlan I 1606-1611/2 (AH 1020)

- Badi I 1611/2 (AH 1020)-1616/7 (AH 1025)

- Rabat I 1616/7 (AH 1025)-1644/5

- Badi II 1644/5-1681

- Unsa II 1681–1692

- Badi III 1692–1716

- Unsa III 1719–1720

- Nul 1720–1724

- Badi IV 1724–1762

- Nasir 1762–1769

- Isma'il 1768–1776

- Adlan II 1776–1789

- Awkal 1787–1788

- Tayyib II 1788–1790

- Badi V 1790

- Nawwar 1790–1791

- Badi VI 1791–1798

- Ranfi 1798–1804

- Agban 1804–1805

- Badi VII 1805–1821

Hamaj Regents

- Muhammad Abu Likayik – 1769–1775/6

- Badi walad Rajab – 1775/6–1780

- Rajab 1780–1786/7

- Nasir 1786/7–1798

- Idris wad Abu Likayik – 1798–1803

- Adlan wad Abu Likayik – 1803

- Wad Rajab – 1804–1806

Maps

-

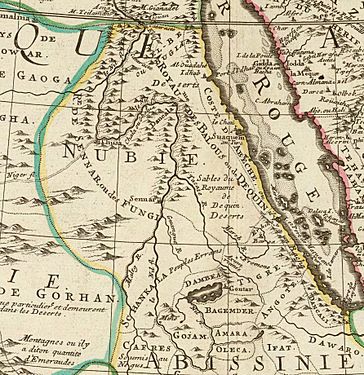

Map by Guillaume Delisle (1701)

-

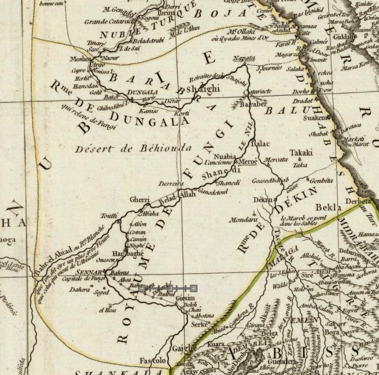

Map by Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville (1749)

-

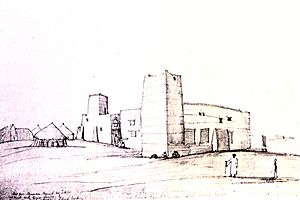

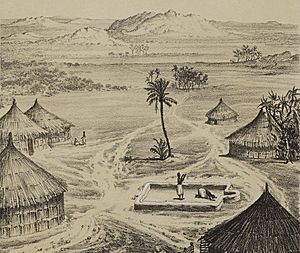

Map by traveller James Bruce, who traversed the country in the early 1770s

See also

In Spanish: Sultanato de Sennar para niños

In Spanish: Sultanato de Sennar para niños

- Funj Chronicle

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

Annotations

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |