Die Linke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids <div style="padding-top:0.3em; padding-bottom:0.3em; border-top:2px solid Lua error in Module:European_and_national_party_data/config at line 227: attempt to index field 'data' (a nil value).; border-bottom:2px solid Lua error in Module:European_and_national_party_data/config at line 227: attempt to index field 'data' (a nil value).; line-height: 1;">

Die Linke

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Chairpersons |

|

| Deputy Chairpersons |

|

| Leaders in the Bundestag |

|

| Secretary | Janis Ehling |

| Founded | 16 June 2007 |

| Merger of | PDS WASG |

| Headquarters | Karl-Liebknecht-Haus Kleine Alexanderstraße 28 D-10178 Berlin |

| Think tank | Rosa Luxemburg Foundation |

| Student wing | Die Linke.SDS |

| Youth wing | Left Youth Solid |

| Membership (June 2025) | |

| Ideology | Democratic socialism Left-wing populism |

| Political position | Left-wing |

| European affiliation | Party of the European Left |

| European Parliament group | The Left in the European Parliament |

| Colours | Red (official) Purple (customary) |

| Bundestag | Lua error in Module:European_and_national_party_data/config at line 227: attempt to index field 'data' (a nil value). |

| Bundesrat | Lua error in Module:European_and_national_party_data/config at line 227: attempt to index field 'data' (a nil value). |

| State Parliaments |

92 / 1,894

|

| European Parliament | Lua error in Module:European_and_national_party_data/config at line 227: attempt to index field 'data' (a nil value). |

| Heads of State Governments |

0 / 16

|

| Party flag | |

|

|

| Website | |

| Lua error in Module:European_and_national_party_data/config at line 227: attempt to index field 'data' (a nil value). | |

|

^ A: A broad left-wing party, it has also been described as far-left by some news outlets. |

|

Die Linke (which means The Left in German) is a political party in Germany. It believes in democratic socialism, which means it wants a society where everyone is equal and has a say. The party was formed in 2007. It came about when two older parties, the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) and Labour and Social Justice – The Electoral Alternative (WASG), joined together.

The Left has roots in the party that used to govern East Germany, called the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED). Today, Die Linke is led by co-chairpersons Ines Schwerdtner and Jan van Aken. The party has 64 seats in the German parliament, known as the Bundestag. This makes it one of the smaller groups in the parliament.

The Left is also active in seven of Germany's sixteen state parliaments. In some states, like Bremen and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, it works with other parties in the government. From 2014 to 2024, the party even led the government in the state of Thuringia. The Left is also part of a larger group of left-wing parties in the European Parliament.

Contents

Party History

Early Beginnings

The main party that came before Die Linke was the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS). This party grew out of the Socialist Unity Party (SED), which was the ruling party in East Germany (GDR). In 1989, when many people were unhappy with the government, the SED started to make changes.

One big change was allowing more freedom, which led to the fall of the Berlin Wall. The SED then changed its name to PDS. It tried to become a more democratic and socialist party. The PDS wanted to support East Germany's independence.

In the first free elections in East Germany in 1990, the PDS came in third place. After Germany became one country again, the PDS gained support in the eastern states. It became a party for people who felt left out. By the 2000s, it was a strong party in most eastern state parliaments. However, it struggled to gain support in the western parts of Germany.

Joining Forces

In 2005, a new left-wing party called Labour and Social Justice – The Electoral Alternative (WASG) was formed. This party was started by people who were unhappy with some government changes. The WASG quickly gained members.

The PDS and WASG decided to work together. The PDS was strong in the east, and WASG had potential in the west. They hoped to win more seats in the German parliament by teaming up. They agreed to run together in elections and then officially merge in 2007. To show this new partnership, the PDS changed its name to the Left Party.PDS.

A well-known politician named Oskar Lafontaine joined WASG, which made the alliance even more popular. In the 2005 federal election, the combined Left.PDS party won 8.7% of the votes and 53 seats. This made them the fourth-largest party in the Bundestag.

Forming Die Linke

The PDS and WASG officially merged on 16 June 2007, forming the new party called The Left (Die Linke). Lothar Bisky and Oskar Lafontaine became the first co-leaders.

The new party quickly became important in western Germany too. It won seats in state parliaments in Bremen, Lower Saxony, Hesse, and Hamburg. This showed that Germany now had five main political parties.

The Left continued to do well in elections in 2009. They won 7.5% in the European elections. They also gained more seats in several state elections. In the state of Saarland, Oskar Lafontaine led the party to a big success, winning 21.3% of the votes.

Federal Elections and Challenges

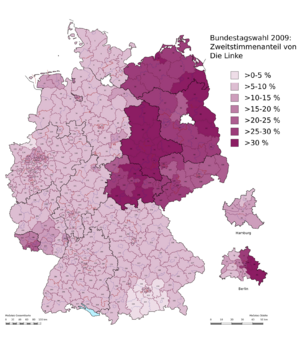

In the 2009 federal election, The Left's support grew to 11.9%. They won 76 seats in the Bundestag, becoming the second most popular party in eastern Germany. They also made a breakthrough in western Germany.

However, the party faced some challenges. In 2010, Oskar Lafontaine stepped down as co-leader due to health reasons. New leaders, Klaus Ernst and Gesine Lötzsch, were elected. The party also faced criticism for not supporting certain candidates in presidential elections.

From 2011 to 2013, The Left lost some support, especially in western states. They lost seats in several state parliaments. In 2012, Gesine Lötzsch resigned, and Katja Kipping and Bernd Riexinger were elected as the new co-leaders.

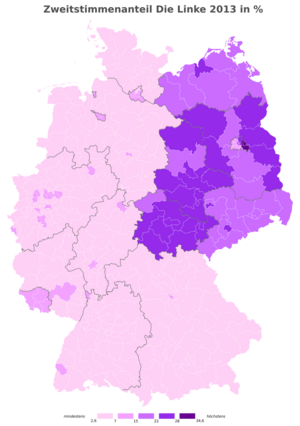

In the 2013 federal election, The Left received 8.6% of the national vote and won 64 seats. They became the main opposition party after the two largest parties formed a coalition government.

A big success came in the 2014 Thuringian state election. The Left won its best state election result ever (28.2%). They formed a government with other parties, and Bodo Ramelow became the first member of The Left to lead a German state government. The party also joined governments in Berlin and Bremen in later years.

Recent Elections and Changes

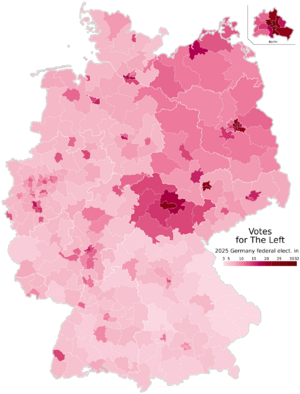

In the 2017 federal election, The Left's vote increased slightly to 9.2% nationally. However, they fell to fifth place because other parties gained more support. They continued to face challenges in state elections.

In 2019, The Left had mixed results. They lost support in the European election. They also lost many votes in the Brandenburg and Saxony state elections. However, in Thuringia, Bodo Ramelow led the party to its best result ever, winning 31.0% of the vote. He was re-elected as Minister-President in 2020.

In 2021, Janine Wissler and Susanne Hennig-Wellsow were elected as the new co-chairs. The party hoped to join a federal government after the 2021 federal election. However, they won only 4.9% of the votes and 39 seats, their lowest result since forming in 2007. They still got seats because they won three direct constituencies.

After the 2021 election, The Left faced more internal problems. Susanne Hennig-Wellsow resigned as co-leader in 2022. Martin Schirdewan was elected as the new co-leader alongside Janine Wissler.

Party Split and New Growth

The 2022 conflict in Ukraine caused disagreements within the party. Some members, like Sahra Wagenknecht, had different views on sanctions against Russia. In October 2023, Wagenknecht and nine other members left The Left to start a new party called the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance. This caused The Left to lose its official group status in the Bundestag.

Despite these challenges, The Left saw new growth. In October 2024, Ines Schwerdtner and Jan van Aken were elected as the new co-leaders. By the end of 2024, the party's membership had grown.

- Gregor Gysi, Sören Pellmann, and Ines Schwerdtner defended Berlin-Treptow – Köpenick, Leipzig II, and Berlin-Lichtenberg respectively. Incumbent Gesine Lötzsch retired in Lichtenberg.

- Ferat Koçak, Pascal Meiser, and Bodo Ramelow flipped Berlin-Neukölln, Berlin-Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg – Prenzlauer Berg East, and Erfurt – Weimar – Weimarer Land II respectively.

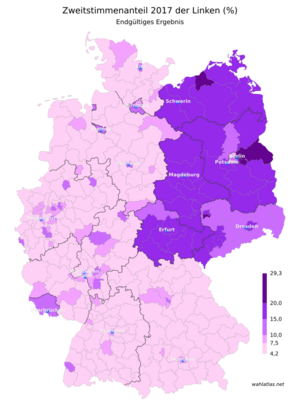

In the early federal election in February 2025, many people thought The Left might not get enough votes to be in the Bundestag. However, the party gained a lot of support during the campaign. A speech by Heidi Reichinnek that criticized another party leader became very popular online.

This led to a big increase in popularity and new members, especially among young people and women. The Left's strong opposition to the AfD party, its ideas on housing and taxes, and its welcoming attitude towards immigrants were seen as strengths.

In the 2025 election, The Left won 8.8% of the vote and 64 seats. This was their best result since 2017. They also won six direct constituencies, including three in Berlin, which was a first for the party in former West Germany. Exit polls showed The Left was the most popular party among voters aged 18–24. By mid-2025, the party had grown to 115,000 members.

What Die Linke Believes In

The Left supports democratic socialism. This means they want a society where everyone is treated fairly and has equal opportunities. They are strongly against fascism and militarism. The party includes different groups, from those who want big changes to those who prefer smaller, more gradual ones.

The Left is sometimes seen as part of the "centre-left" in German politics. Some journalists describe it as "far-left" or "left-wing populist."

Economic Ideas

The Left wants the government to spend more money on public services. This includes things like education, research, culture, and improving roads and buildings. They also want to increase taxes for large companies and wealthy individuals.

The party aims to make taxes fairer, so people with lower incomes pay less. They want to close tax loopholes that mainly help rich people. The Left also wants stronger rules for financial markets to stop risky speculation. They support strengthening laws against monopolies and helping smaller businesses work together.

Other economic goals include:

- More power and self-determination for workers.

- Banning fracking.

- Stopping the sale of public services to private companies.

- Setting a national minimum wage.

Foreign Policy Ideas

In terms of foreign policy, The Left wants to see less military action around the world. They believe in international disarmament. They do not want German soldiers (Bundeswehr) to be involved in conflicts outside of Germany.

The party wants U.S. troops to leave Germany. They also suggest replacing NATO with a new system for global safety that includes Russia. The Left believes Germany's foreign policy should focus on peaceful talks and working together, not on fighting.

The party has criticized Germany's weapons sales to countries involved in conflicts. They support canceling debts for developing countries and increasing aid to them. They also want to see the United Nations reformed to be fairer to all countries. The Left was against the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Views on Russia

The party has mixed views on the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. While the party leadership has condemned Russia's actions, some older members have a strong connection to Russia. The party has stated that Ukraine should not receive support from Germany if there are fascists in its government.

Views on China

The Left generally has a friendly view towards China. Some members have criticized the European Union for taking a confrontational approach towards China.

Views on Israel

The Left has shown solidarity with Israel after attacks. They have condemned attacks by Hamas. The party believes Israel has a right to exist but also states that Israel's military actions must follow international law. They call for the release of all hostages and want the German government to stop supplying weapons to Israel. The party supports a two-state solution for peace in the region.

The Left has also faced internal debates and disagreements regarding its stance on Israel and Palestine.

How Die Linke is Organized

Die Linke has branches in all 16 German states. These state branches then have smaller local groups in districts or cities. The smallest groups are called grassroots organizations.

The party also has a youth group called Left Youth Solid and a student group called The Left.SDS. They are also connected to several research and education groups, like the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

The party is led by a 26-member Party Executive Committee (PEC). Seven of these members are part of the party's main leadership team. This includes two federal co-chairpersons. At least one of these co-chairs must be female. It is also a tradition for one leader to be from eastern Germany and one from western Germany.

The PEC is chosen at a regular party congress. This congress also decides the party's main goals and rules. The leaders of the party's group in the Bundestag are also very important. Sometimes, there are disagreements between the party's federal leaders and its parliamentary group leaders.

The Left has a unique system of internal groups, or "factions." These factions are officially recognized in the party's rules. Groups with enough members can send representatives to party congresses. There are also about 40 working groups within the party.

The party has different types of factions:

- Anti-Capitalist Left (AKL): Wants to strengthen the party's anti-capitalist ideas. They believe the party should only join governments if certain conditions are met, like no privatization or military operations.

- Communist Platform (KPF): This group is less critical of East Germany's past. They support traditional Marxist ideas and aim for a new socialist society.

- Democratic Socialist Forum (fds): This group is more reform-oriented. They focus on civil rights and social progress. They support working with other parties like the SPD and Greens.

- Ecological Platform (ÖPF): This group promotes green politics and eco-socialism. They are critical of capitalism and support ideas like "degrowth."

- Emancipatory Left (Ema.Li): This group is in the middle of the party's different wings. They support radical democracy and social movements.

- Socialist Left (SL): This group focuses on workers' rights and the labor movement. Many of its leaders were part of the WASG party before the merger.

Members and Voters

| {{#chart:Linke membership.chart}} |

Studies show that in 2021, The Left's members included many blue-collar and white-collar workers. Many members also had university degrees and were part of trade unions.

After the merger with WASG, The Left became more popular among working-class and poorer voters. In recent years, the party has also gained popularity among young people. In 2021, The Left was twice as popular among voters under 25 than among those over 70. In the 2025 federal election, they were the most popular party among voters aged 18–24.

The PDS started with 170,000 members in 1990 but saw its numbers decline. When The Left was formed in 2007, it had 71,000 members. The party's membership grew to a peak of 78,000 in 2009. After some declines, membership started to grow again, especially in 2024 and 2025. By mid-2025, The Left had grown to 115,000 members. A large number of new members were young people and women.

Where Members Live

A big part of The Left's support comes from the eastern states of Germany (the former GDR). However, the party has grown in the western states over the years. In the 2025 election, most of their votes came from western Germany. Between 2016 and 2018, most new party members were from the western states. By 2021, about half of The Left's members were from the west.

Despite this, the party has lost some of its strength in western state parliaments since 2010. In the east, The Left's voters and members tend to be older. In the west, more of the party's members are men.

Women in the Party

The Left has a good representation of women among its elected officials. The party has a rule that at least half of its leadership positions and representatives should be female. In 2021, for the first time, two women were elected as federal co-chairs.

The percentage of women in the party's membership has also increased. By June 2025, 44.5% of The Left's members were female, which is the highest percentage among German parties. After the 2009, 2013, 2017, and 2021 federal elections, more than half of The Left's members in the Bundestag were women.

Election Results

Federal Parliament (Bundestag)

| Election | Constituency | Party list | Seats | +/– | Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||||

| 2009 | 4,791,124 | 11.1 (#3) | 5,155,933 | 11.9 (#4) |

76 / 622

|

Opposition | |

| 2013 | 3,585,178 | 8.2 (#3) | 3,755,699 | 8.6 (#3) |

64 / 631

|

Opposition | |

| 2017 | 3,966,035 | 8.6 (#4) | 4,296,762 | 9.2 (#5) |

69 / 709

|

Opposition | |

| 2021 | 2,306,755 | 5.0 (#7) | 2,269,993 | 4.9 (#7) |

39 / 735

|

Opposition | |

| 2025 | 3,932,584 | 7.9 (#5) | 4,355,382 | 8.8 (#5) |

64 / 630

|

Opposition | |

European Parliament

| Election | List leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | EP Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Lothar Bisky | 1,968,325 | 7.48 (#5) |

8 / 99

|

New | The Left - GUE/NGL |

| 2014 | Gabi Zimmer | 2,167,641 | 7.39 (#4) |

7 / 96

|

||

| 2019 | Martin Schirdewan | 2,056,010 | 5.50 (#5) |

5 / 96

|

||

| 2024 | 1,091,268 | 2.74 (#8) |

3 / 96

|

State Parliaments (Länder)

| State parliament | Election | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | 2021 | 173,295 | 3.6 (#6) |

0 / 154

|

No seats | |

| Bavaria | 2023 | 200,795 | 1.5 (#7) |

0 / 203

|

No seats | |

| Berlin | 2023 | 184,954 | 12.2 (#4) |

22 / 147

|

Opposition | |

| Brandenburg | 2024 | 44,692 | 3.0 (#6) |

0 / 88

|

No seats | |

| Bremen | 2023 | 137,676 | 10.9 (#4) |

10 / 87

|

SPD–Greens–Left | |

| Hamburg | 2025 | 487,729 | 11.2 (#4) |

15 / 123

|

TBA | |

| Hesse | 2023 | 86,821 | 3.1 (#7) |

0 / 133

|

No seats | |

| Lower Saxony | 2022 | 98,585 | 2.7 (#6) |

0 / 146

|

No seats | |

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | 2021 | 90,865 | 9.9 (#4) |

9 / 79

|

SPD–Left | |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 2022 | 146,634 | 2.1 (#6) |

0 / 195

|

No seats | |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 2021 | 48,210 | 2.5 (#7) |

0 / 101

|

No seats | |

| Saarland | 2022 | 11,689 | 2.6 (#6) |

0 / 51

|

No seats | |

| Saxony | 2024 | 104,888 | 4.5 (#6) |

6 / 119

|

Opposition | |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 2021 | 116,927 | 11.0 (#3) |

12 / 97

|

Opposition | |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 2022 | 23,035 | 1.7 (#7) |

0 / 69

|

No seats | |

| Thuringia | 2024 | 157,641 | 13.1 (#4) |

12 / 88

|

Opposition |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: La Izquierda (Alemania) para niños

In Spanish: La Izquierda (Alemania) para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |