Tintern Abbey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tintern Abbey |

|

|---|---|

| Native name Welsh: Abaty Tyndyrn |

|

|

|

| Type | Abbey |

| Location | Tintern, Monmouthshire |

| Built | 1131 |

| Governing body | Cadw |

|

Listed Building – Grade I

|

|

| Official name: Abbey Church of St Mary (Tintern Abbey) including monastic buildings | |

| Designated | 29 September 2000 |

| Reference no. | 24037 |

| Official name: Tintern Abbey inner precinct | |

| Reference no. | MM102 |

| Official name: Tintern Abbey watergate | |

| Designated | 15 July 1998 |

| Reference no. | MM265 |

| Official name: Tintern Abbey precinct wall | |

| Reference no. | MM157 |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

Tintern Abbey (in Welsh: Abaty Tyndyrn) is a stunning ruined abbey located next to the village of Tintern in Monmouthshire, Wales. It sits on the Welsh side of the River Wye, which forms the border between Wales and Gloucestershire in England at this spot.

A powerful lord named Walter de Clare started the abbey on May 9, 1131. It was the very first Cistercian monastery in Wales and only the second in all of Britain.

After the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1500s, the abbey became a ruin. Since the 1700s, its beautiful remains have inspired many poets and painters. Today, Cadw, a Welsh government body, looks after the site. About 70,000 people visit Tintern Abbey every year.

Contents

History of Tintern Abbey

How the Abbey Started

Long ago, there's a story about Tewdrig, a king of Glywysing. He retired to live as a hermit near the river at Tintern. He later led his son's army to victory against the Saxons but died in battle.

The Cistercian Monks

The Cistercians were a special group of monks who started in 1098. They were a stricter branch of the Benedictines, aiming to live very simply and follow the rules of Saint Benedict closely. They believed their abbeys should be built far from towns and villages. They also didn't want tall bell towers, keeping things simple.

Cistercian monks focused on both prayer and work. They had two groups: the monks, who prayed and studied, and the lay brothers, who were workers who helped with manual labor. This way of life was very successful, and by 1151, there were 500 Cistercian abbeys in Europe. Their main rules were obedience, poverty, chastity, silence, prayer, and hard work.

In 1128, the first Cistercian monks came to England at Waverley Abbey. Just three years later, in 1131, Walter de Clare founded Tintern Abbey. The monks at Tintern came from an abbey in France called L'Aumône. Over time, Tintern Abbey even started two of its own daughter abbeys: Kingswood in England and Tintern Parva in Ireland.

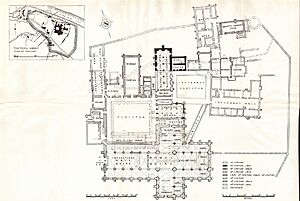

Building the Abbey: 1131–1536

The ruins you see today at Tintern Abbey show buildings from over 400 years. Not much is left from the very first buildings in 1131. Some old walls are still there, and two small cupboards for books in the cloisters are from this early time. The first church was smaller and a bit further north than the main building today.

Most of the abbey was rebuilt in the 1200s. This started with the cloisters (covered walkways) and living areas. The grand church was built between 1269 and 1301. The first church service in the new main altar area happened in 1288. The church was officially blessed in 1301, but building work continued for many more years.

Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk, who was the lord of Chepstow, gave a lot of money to the abbey. He was a huge help in rebuilding the church. His family crest was even put in the abbey's east window to thank him.

The large, beautiful church you see today is a great example of the Decorated Gothic style of its time. It has a cross shape with a main hall (nave), two chapels in each arm of the cross (transept), and a square-ended area for the altar (chancel). The abbey is built from Old Red Sandstone, which has colors like purple, buff, and grey. It is 228 feet long from east to west, and the transept is 150 feet long.

In 1326, King Edward II of England stayed at Tintern for two nights. When the Black Death arrived in 1349, it was hard to find new lay brothers to work. The abbey also faced money problems in the early 1400s because of the Glyndŵr Rising, a Welsh uprising against the English kings. During this time, some abbey properties were destroyed.

The Abbey Becomes a Ruin

During the reign of King Henry VIII of England, a big change happened called the Dissolution of the Monasteries. This ended monastic life in England, Wales, and Ireland. On September 3, 1536, the abbot (the head monk) of Tintern Abbey gave up the abbey and all its lands to the King. This ended a way of life that had lasted for 400 years.

Valuable items from the abbey were sent to the King's treasury. The abbot was given a pension (money to live on). The abbey building was given to Henry Somerset, 2nd Earl of Worcester. The lead from the roof was sold, and the buildings slowly began to fall apart.

Abbey Buildings and Design

The Church

The front of the church, facing west, has a large window with seven sections. This part was finished around 1300.

The nave, or main hall, has six sections. It used to have arched walkways on both the north and south sides.

Monks' Choir and Presbytery

The presbytery, where the main altar was, has four sections and a huge east window. Most of the decorative stone work in the window is gone, except for the central column.

Cloister (Covered Walkway)

The cloister kept its original width, but it was made longer during the 1200s rebuilding, making it almost square.

Book Room and Sacristy

The book room and sacristy (a room for sacred items) were built at the very end of the second abbey's construction, around 1300.

Chapter House

The chapter house was where the monks met daily. They discussed abbey business, confessed, and listened to readings from their rules.

Monks' Dormitory and Latrine

The monks' dormitory (sleeping area) took up almost the entire upper floor of the east building. The latrines (toilets) had two levels, accessible from both the dormitory and the day-room below.

Refectory (Dining Hall)

The refectory, or dining hall, was built in the early 1200s, replacing an older hall.

Kitchen

Not much is left of the kitchen, which served both the monks' dining hall and the lay brothers' dining hall.

Infirmary (Hospital)

The infirmary, which was 107 feet long and 54 feet wide, was where sick and elderly monks stayed. They had small rooms (cubicles) in the side aisles. These rooms were originally open but were enclosed in the 1400s, and each even got a fireplace.

Abbot's Residence

The abbot's (head monk's) living quarters were built in two stages. They started in the early 1200s and were greatly expanded in the late 1300s.

Industry Around the Abbey

After the abbey was closed, the area around it became industrial. The first wireworks started in 1568, and more factories and furnaces grew up the Angidy valley. People made charcoal in the woods to fuel these operations. The hillside above was also quarried for lime, which was used in a kiln that ran for about 200 years.

Because of all this industry, the abbey site became somewhat polluted. Local workers even lived in the ruins. Some visitors were surprised by the factories and cottages built near the abbey.

However, not everyone was bothered by the industry. Some visitors, like Joseph Cottle and Robert Southey, even went to see the ironworks at midnight during their tour in 1795. Artists also painted the industrial scenes. A 1799 print of the abbey by Edward Dayes shows a boat landing near the ruins with a local cargo boat. It also shows some houses and smoke rising from a lime kiln in the background.

Visiting Tintern Abbey

1700s and 1800s Tourism

By the mid-1700s, it became popular to visit "wilder" parts of the country. The Wye Valley was especially famous for its beautiful and romantic scenery. The ivy-covered Tintern Abbey became a popular spot for tourists.

One of the earliest pictures of the abbey was in a series of engravings by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck in 1732. These pictures were often made to please landowners. But real tourism started to grow in the following decades. The "Wye Tour" became famous after Dr. John Egerton began taking friends on boat trips down the valley.

Many visitors came, including Francis Grose, who wrote about the abbey in his Antiquities of England and Wales. He noticed that the ruins were being tidied up for tourists. He also felt the site was too neat and lacked the "gloomy solemnity" he expected from religious ruins.

Another important visitor was the Rev. William Gilpin, who published his travel notes in Observations on the River Wye (1782). He found the abbey "very enchanting," even with the poor residents and their simple homes nearby. Gilpin's book helped make the Wye tour even more popular. It also encouraged people to sketch, paint, and write about their travels.

Local guidebooks also became available. Charles Heath's Descriptive Accounts of Tintern Abbey, first published in 1793, was sold at the abbey itself. This book was updated many times and included history and stories about the building.

Until the early 1800s, the local roads were rough. The easiest way to reach the abbey was by boat. The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge almost rode his horse off a cliff trying to find Tintern in the dark! It wasn't until 1829 that a new main road, the Wye Valley turnpike, was finished. Later, in 1876, the Wye Valley Railway opened a station for Tintern.

Modern Times: 1900s and 2000s

In 1901, the British Crown bought Tintern Abbey from the Duke of Beaufort for £15,000. The site was recognized as a very important national monument. While some repairs had been done earlier, serious archaeological work and maintenance began around this time.

In 1914, the Office of Works took over the abbey. They did major repairs and some rebuilding. They even removed the ivy that early tourists thought was so romantic! In 1984, Cadw became responsible for the site. Tintern Abbey was given a Grade I listing on September 29, 2000, meaning it's a building of exceptional interest. The arch of the abbey's watergate, which led to the River Wye, was also listed as Grade II.

Tintern Abbey in Art

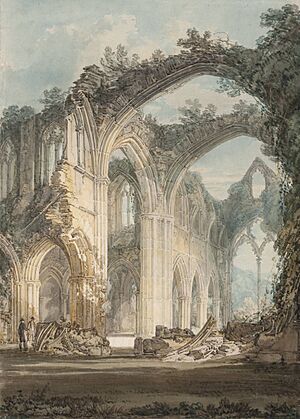

Many painters came to Tintern Abbey to capture its beauty. Artists like Francis Towne (1777), Thomas Gainsborough (1782), Thomas Girtin (1793), and J. M. W. Turner (1794–95) painted detailed parts of the abbey's stonework. Later, Samuel Palmer and Thomas Creswick also painted the ruins. Even amateur artists, like the father and daughter Ellis, made watercolors of the refectory windows. The photographer Roger Fenton used his new art form to show the decay of the building and how light affected it.

Artists also focused on how light and weather changed the abbey's look. Charles Heath, in his 1806 guide, talked about the amazing effect of the harvest moon shining through the main window. Other paintings show the abbey by moonlight, sometimes with tourist guides holding torches. Once the railway arrived, special trips were even organized in the 1880s to see the harvest moon through the abbey's rose window.

Different light effects appear in other paintings, such as sunsets by Samuel Palmer and Benjamin Williams Leader. Turner also did a color study where the distant abbey appears as a "dark shape" under slanting sunlight.

Tintern Abbey in Stories and Poems

Poetry Inspired by the Abbey

Many poets have been inspired by Tintern Abbey. While some early poets like William Mason and Thomas Gray visited, they didn't write poems specifically about it. However, the abbey soon appeared in many poems about the area.

One of the most famous poems is William Wordsworth’s "Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey" (1798). He didn't actually mention the ruins directly in the poem. Instead, he remembered an earlier visit and thought about how that memory had helped him.

Other poets wrote about the abbey's past. George Richards' poem, "Tintern Abbey; or the Wandering Minstrel," described the site as it used to be. Another poem, "The Legend of Tintern Abbey," tells a story about how Walter de Clare supposedly built the abbey to make up for murdering his wife.

In the 1800s, some poems reflected the religious debates of the time. Frederick Bolingbroke Ribbans wrote "Tintern Abbey: a Poem" (1854) to argue against the idea of the abbey returning to its old religious ways. He preferred to see it as a ruin rather than a place "with falsehood fill’d."

Later, in the 1900s, American poets also found inspiration. John Gould Fletcher’s "Elegy on Tintern Abbey" responded to Wordsworth's hopeful view by talking about the problems of industrialization and World War I. After visiting in 1967, Allen Ginsberg wrote "Wales Visitation" about his experience of feeling connected to the Welsh valley and seeing "clouds passing through skeleton arches of Tintern Abbey."

Fictional Stories

Tintern Abbey has also been a setting for novels. In 1816, Sophia Ziegenhirt wrote a three-volume Gothic horror novel called The Orphan of Tintern Abbey. It starts with a description of the abbey.

In the 1900s, the abbey became a popular setting for ghost stories. "The Ghost of Tintern Abbey" (1901) by Mrs. Arthur Traherne was about solving a murder. Another story, "The Troubled Spirit of Tintern Abbey" (1910), was about a ghost from Purgatory asking for prayers. Later, Henry Gardner wrote a novella called "The Ghost of Tintern Abbey" in 1984.

More recently, Gordon Master's novel The Secrets of Tintern Abbey (2008) tells a story about the abbey's medieval history, covering the 400 years of the Cistercian community until it was closed down.

Images for kids

-

The Abbey on a bend of the Wye, William Havell, 1804

-

Local use of the ruins,

P. J. de Loutherbourg, 1805 -

A J. M. W. Turner light effect, watercolour, 1828

-

Ruins against the hillside, Samuel Palmer, 1835

-

Abbey interior, 1858/1862, photo by Roger Fenton

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |