Universal Esperanto Association facts for kids

|

Universala Esperanto-Asocio

|

|

Logo of UEA

|

|

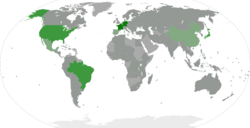

Individual members by country

1-100 members 101-200 members 201-300 members 301-400 members |

|

| Abbreviation | UEA |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1908 |

| Founder | Hector Hodler |

| Purpose | promote the use of Esperanto |

| Headquarters | Central Office |

| Location |

|

|

Region

|

World |

|

Official language

|

Esperanto |

|

President

|

Duncan Charters |

|

Vice-President

|

Fernando Maia |

|

General Director

|

Martin Schäffer |

|

Key people

|

Ivo Lapenna |

|

Main organ

|

Central Committee |

| Affiliations | UN, UNESCO |

The World Esperanto Association (Esperanto: Universala Esperanto-Asocio, UEA) is the biggest international group for people who speak Esperanto. Esperanto is a special language created to help people from different countries talk to each other easily. UEA has many members around the world. In 2015, it had over 5,500 individual members in 121 countries. It also had over 9,200 members through national groups in 214 countries. About 70 national Esperanto groups are connected to UEA.

The current president of UEA is Prof. Duncan Charters. The association publishes a magazine called Esperanto. This magazine shares news with members about what is happening in the Esperanto community.

UEA was started in 1908 by a Swiss journalist named Hector Hodler and others. Its main office is in Rotterdam, Netherlands. The organization works closely with the United Nations and has an office at the UN headquarters in New York City.

Contents

How the World Esperanto Association Works

The World Esperanto Association has two main types of members.

- Individual members join directly. They pay a fee to the main office in Rotterdam or to a local representative. These members get services from UEA.

- Associate members (called asociaj membroj) are part of other groups that have joined UEA. These groups can be national or special interest clubs.

UEA has a special board called the Komitato. This board is like a parliament for the association. Members of the Komitato are chosen in different ways:

- National Esperanto groups send at least one member to the Komitato. Larger groups send more.

- For every 1,000 individual members, one person can be chosen for the Komitato.

- The other two groups can also choose more Komitato members.

The Komitato chooses another group called the Estraro. The Estraro then picks a general director and sometimes another director. The general director and other staff work at the main UEA office in Rotterdam.

Individual members can also become a delegito, which means 'delegate'. A delegate is a local contact person for Esperanto and UEA members in their town. A ĉefdelegito (chief delegate) is chosen by the UEA office to collect membership fees in a country.

Youth Section: TEJO

TEJO, which stands for the World Esperanto Youth Organization, is the youth part of UEA. Every year, TEJO organizes an International Youth Congress of Esperanto (Internacia Junulara Kongreso). This event happens in a different place each year. The IJK is a week-long gathering with concerts, talks, and trips. Hundreds of young people from all over the world attend.

Just like UEA, TEJO has its own Komitato and connected groups for different countries and interests. A volunteer from TEJO also works at the main office in Rotterdam.

National Esperanto Groups

The first national Esperanto group started in France in 1898. Soon after, many other national groups formed in different countries. Since 1933-1934, these national groups have sent representatives to the UEA Komitato. This made UEA a larger group that connects many national organizations. These groups were first called Naciaj Societoj (national societies) but are now known as Landaj Asocioj (country associations).

When UEA first accepted national groups, it had some rules for them:

- They needed at least 100 members.

- They had to be well-organized.

- They had to be neutral, meaning they had no political or religious goals. They also had to be open to everyone in their country.

Over time, these rules were updated. For example, in 1980, the rules changed to say that a national group did not have to be neutral itself, but it had to respect UEA's neutrality.

Specialist Esperanto Groups

Specialist groups are similar to national groups but focus on specific interests. They are divided into two types:

- Neutral organizations can join UEA like national groups. These are called aliĝintaj fakaj asocioj (affiliated specialist associations). Examples include Esperanto doctors and Esperanto teachers.

- Other organizations work with UEA but do not send representatives to the Komitato. They might have a space at the World Congress. Examples are Esperanto vegetarians or Esperanto Catholics. Some do not join because of money reasons, or because they are not neutral.

TEJO, the youth section, also has two connected specialist groups: Esperanto cyclists and Esperanto rock music fans.

What the World Esperanto Association Does

Publications and Resources

UEA publishes Esperanto, which is a very important magazine for Esperanto speakers. It started in 1905, even before UEA was founded. Hector Hodler took it over in 1907 and made it the official UEA magazine in 1908. UEA also used to publish a Yearbook (Jarlibro de UEA) for over 100 years.

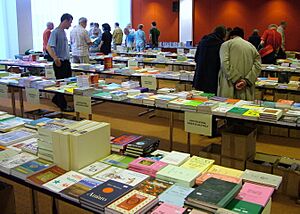

UEA publishes books and has the largest mail-order Esperanto bookstore in the world. It offers over 6,000 book titles, CDs, and other items. The association also has an information center and an important Esperanto library called the Hector Hodler Library. UEA has a network of local representatives around the world, called the Delegita Reto. These people can give information about their local area or their job field.

Events and Gatherings

UEA organizes the yearly World Esperanto Congress (Universala Kongreso de Esperanto). This big event brings together 1,500 to 3,000 people in a different city each year. The first congress was in 1905. Since 1933–1934, UEA has been in charge of this annual event. Recent congresses have been held in places like Białystok, Poland (the hometown of L. L. Zamenhof, who created Esperanto), Havana, Copenhagen, Hanoi, Reykjavík, Buenos Aires, Lille, Nitra, Seoul, Lisbon, Lahti, Montreal and Turin. In 2020 and 2021, the congresses were held online because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Congresses are planned for Arusha, Tanzania in 2024 and Brno, Czech Republic in 2025.

The UEA headquarters in Rotterdam also holds an Open Day twice a year, in spring and autumn.

Working with Other Organizations

UEA works with many important international groups. It has special connections with the United Nations (UN), UNESCO, UNICEF, and the Council of Europe. It also works with the Organization of American States. UEA helps the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) with language standards. It is also active in sharing information within the European Union and other international meetings. UEA is a member of the European Language Council, which helps people learn about languages and cultures.

In May 2011, UEA became an Associate Member of the International Information Centre for Terminology (Infoterm).

Grabowski Prize

The Grabowski Prize is an award given to young writers who create works in Esperanto. It is managed by the Antoni Grabowski Foundation, which is part of UEA. The prize is named after Antoni Grabowski, who is known as "the father of Esperanto poetry." The top three winners receive money prizes.

Past Winners

Ulrich Becker, who publishes books in and about Esperanto, won the Grabowski Prize (Premio Grabowski) in 2005. He was recognized for his work in publishing Esperanto literature. He also publishes a magazine called Beletra Almanako, which features Esperanto stories and poems.

A Brief History of the World Esperanto Association

Early Days of Esperanto

The first Esperanto clubs started in towns, with the one in Nuremberg, Germany, being the first in 1888. Later, national Esperanto groups began to form, starting with France in 1898. The creator of Esperanto, L. L. Zamenhof, wanted an international group to exist. The first World Congress of Esperanto in 1905 helped create a committee to organize future congresses.

People who spoke Esperanto agreed that the movement needed to do two main things: share information internationally and organize the world congresses. However, they disagreed on which group should be in charge of these tasks and how to pay for them.

In 1906, a French general named Hyppolyte Sebert started his own "Central Office of the Esperantists" in Paris. It collected information about the movement. In 1907, Zamenhof created a "Language Committee" (which later became the Akademio de Esperanto) to help guide the Esperanto language.

In 1908, Hector Hodler and other young Esperanto speakers started the Universala Esperanto-Asocio (UEA) in Geneva. This group was based on individual members joining directly. Hodler believed that a global cause like Esperanto needed one strong international group.

At first, the national Esperanto groups saw UEA as a rival. They worried about dividing the movement. They also felt that promoting Esperanto and teaching it was their job, and they didn't want UEA to take new Esperanto speakers away from them.

The national groups tried to create their own international organization. But these efforts stopped in 1914 when World War I began. The war forced many Esperanto activities and planned congresses to be canceled.

UEA's First Years

The first UEA was only for individual members. Members in a town would meet and choose a delegito (delegate). The delegate would collect membership fees and send them to the main office in Geneva. They also represented local members internationally. The delegates would vote and choose the Komitato.

Hector Hodler was the director of UEA from 1908 to 1920. He also owned and published the Esperanto magazine. From the start, UEA published a Yearbook (Jarlibro) with information about the association and delegate addresses.

Hodler wanted to include different specialist groups within UEA. For example, the Universala Medicina Esperanto-Asocio (Esperanto Medical Association) started in 1908. He hoped these specialists would join UEA instead of forming separate groups. He also thought about working with businesses, like hotels, that would give discounts to UEA members.

Hodler imagined UEA growing to have hundreds of thousands of members. However, UEA never had more than 10,000 members in its early years.

Changes After World War I

After World War I, the Esperanto movement met again in 1920. They created a new system to organize the movement, which was agreed upon in 1922. This system included:

- UEA, the international members' group in Geneva.

- A new group called the Konstanta Komitato de la Naciaj Societoj (Permanent Committee of the National Associations) to represent national groups.

- Another new group called the Internacia Centra Komitato de la Esperanto-Movado (International Central Committee of the Esperanto Movement), which managed shared tasks and money.

This system only lasted a few years. The leaders realized there was too much overlap between the different groups. In 1932, UEA and some national groups stopped paying their contributions. This led to a new plan to completely change how the movement was organized.

The 'New UEA' and Its Challenges

In 1933, at a congress in Cologne, UEA and the national groups agreed to make UEA the main organization for the international Esperanto movement. In 1934, UEA members accepted new rules. This 'new UEA' became a group that connected national associations and also had individual members.

The highest body of UEA was still the Komitato. It included representatives from national groups, individual members, and other chosen experts. Since 1947, these groups have been called komitatanoj A, komitatanoj B, and komitatanoj C.

Even though national groups had more representatives, all UEA leaders had to be individual members. Important services, like the Yearbook, were still only for individual members.

UEA then took over the responsibilities of the earlier international groups. It also became responsible for organizing the yearly World Congress of Esperanto.

In 1936, there was a disagreement within UEA. The board decided to move the headquarters from Geneva to London to save money. However, some former leaders disagreed. This led to a split, and many national groups and individual members left to form a new group called the Internacia Esperanto-Ligo (IEL). A smaller group remained as the "Genevan UEA."

UEA After World War II

The international Esperanto movement continued through World War II with the IEL headquarters near London. After the war, the IEL and the Genevan UEA merged.

Ivo Lapenna, a law professor from London, made big changes to the association in the 1950s. The main office moved from Heronsgate to Rotterdam. The editor of the Esperanto magazine became a paid job. In 1980, the association updated its rules again.

After the war, the number of staff at UEA grew. Before the war, there were only a few people working. After the war, UEA sometimes had ten or more employees, including a congress manager, a book seller, and a librarian.

Lapenna started a "prestige policy," spending money to make Esperanto more recognized. He led efforts to get UNESCO to support Esperanto, which happened in 1954. This made him famous in Esperanto circles. After working for UEA for over 30 years, Lapenna left in 1974.

During the time known as the Cold War, UEA faced challenges because it had members and groups in countries with different political systems. The collapse of the Soviet Union and its allies between 1989 and 1991 changed the international situation for UEA.

See also

In Spanish: Asociación Universal de Esperanto para niños

In Spanish: Asociación Universal de Esperanto para niños

- Category:Presidents of the World Esperanto Association

- World Esperanto Youth Organization (TEJO)

- Sennacieca Asocio Tutmonda, another global Esperanto organization

- World Congress of Esperanto

- Terminologia Esperanto-Centro