V. S. Ramachandran facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

V. S. Ramachandran

|

|

|---|---|

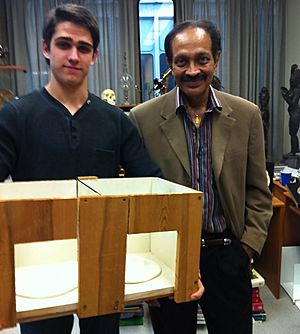

Ramachandran at the 2011 Time 100 gala

|

|

| Born |

Vilayanur Subramanian Ramachandran

10 August 1951 |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | Research in neurology, visual perception, phantom limbs, synesthesia, autism, body integrity identity disorder, mirror therapy |

| Awards | Henry Dale Medal (2005), Padma Bhushan (2007), Scientist of the Year (ARCS Foundation) (2014) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | University of California, San Diego |

Vilayanur Subramanian Ramachandran (born August 10, 1951) is an Indian-American brain scientist, also known as a neuroscientist. He is famous for his many experiments and ideas in how the brain affects behavior. He also invented the mirror box, a simple but clever tool. Ramachandran is a special professor at the UCSD's Department of Psychology. He also leads the Center for Brain and Cognition there.

After getting his medical degree in India, Ramachandran studied brain science at Cambridge. He earned his PhD there in 1978. Much of his work has been about how the brain controls behavior and how we see things. He first studied human vision. Later, he explored bigger brain mysteries like phantom limbs and phantom pain.

Ramachandran also created the world's first "phantom limb amputation" using his mirror therapy. This therapy is now widely used. It helps reduce phantom pains and can even make phantom sensations disappear over time. It also helps stroke patients regain control of weak limbs.

Ramachandran has written popular books like Phantoms in the Brain (1998) and The Tell-Tale Brain (2010). These books describe his studies of people with unusual brain conditions. These include synesthesia (where senses mix, like seeing colors for numbers) and Capgras syndrome (where someone believes a loved one is an impostor). Ramachandran has also shared his work in many public talks, including for the BBC and two TED talks. He has received many awards for his science and for making science easy to understand.

Contents

About Vilayanur Ramachandran

Ramachandran was born in 1951 in Tamil Nadu, India. His mother had a degree in mathematics. His grandfather, Alladi Krishnaswamy Iyer, helped write India's constitution.

Ramachandran's father, V. M. Subramanian, was an engineer. He worked for the U.N. and was a diplomat in Bangkok, Thailand. Ramachandran went to schools in Madras (now Chennai) and British schools in Bangkok.

His father wanted him to be a doctor. So, Ramachandran earned a medical degree (M.B.B.S.) from Stanley Medical College in Chennai, India.

In 1978, Ramachandran earned his PhD from Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. Later, he moved to the U.S. He spent two years at Caltech as a research fellow. In 1983, he became an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, San Diego. He became a full professor there in 1988. Today, he is a distinguished professor at UCSD. He directs the Center for Brain and Cognition. He also works with students and researchers on new ideas in brain science. Since 2019, Ramachandran is also a professor in the UCSD Medical School's Neurosciences program. He is also an adjunct professor at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

In 1987, Ramachandran married Diane Rogers-Ramachandran, who is also a scientist. She often works with him on his research. They have two sons, Chandramani and Jaya.

Ramachandran's scientific work has two main parts. From the early 1970s to the late 1980s, he focused on how humans see, especially how we see depth (stereopsis). He started publishing research in this area in 1972.

In 1991, Ramachandran was inspired by research on how the brain can change. This research showed that the brain could reorganize itself after a finger was removed. Ramachandran was one of the first to see that brain imaging could show these changes in humans after an amputation. He then started studying phantom limbs. Later, he studied other brain mysteries.

Ramachandran has faced some doubts about his ideas. He has said that he has explored many areas. These include how we see, phantom limbs, and conditions like Capgras syndrome and synesthesia.

Ramachandran often uses simple tools in his research. He might use mirrors or old-fashioned stereoscopes. He does not always use complex brain imaging like fMRI. He believes in using intuition to study the brain. He once said that intuition helps you start, then you need studies. He also said that fancy technology can make you think you understand things when you don't. He prefers simple experiments to stay creative.

Brain Research and Theories

Understanding Phantom Limbs

When an arm or leg is removed, many patients still feel the missing limb very strongly. This is called a "phantom limb." About 80% of amputees experience this. Ramachandran built on earlier work by other scientists. He thought that phantom limbs were linked to how the adult human brain can change and reorganize itself. To test this, he worked with amputees. He wanted to see if phantom limbs could "feel" things applied to other body parts.

In 1992, Ramachandran worked with other researchers. They used a special brain scan called MEG. They showed that there were measurable changes in the brain's sensory area of a patient who had an arm amputation.

Ramachandran believed these brain changes were related to the non-painful sensations he saw in other patients. Later research found that painful phantom limbs were more linked to brain changes than non-painful ones. Recent studies also show that nerves outside the brain are involved in painful phantom limb feelings. Research continues to find more exact explanations.

Mirror Therapy for Pain Relief

Many people consider mirror box therapy for amputees to be Ramachandran's most important invention.

Ramachandran thought that phantom pain might happen because different parts of an amputee's nervous system don't match up. The visual system sees the limb is gone. But the somatosensory system (which feels touch and limb position) still thinks the limb is there. The mirror box is a simple device that uses a mirror. It reflects an amputee's healthy arm. This makes it look like the missing arm is still there.

Patients put their healthy arm through a hole in the side of a box. Inside is a mirror. When they look into the box, they see their arm and its reflection. It looks like they have two arms. Ramachandran then asked them to move their real arm and, in their mind, their phantom arm. For example, they could pretend to conduct an orchestra. Patients felt like they had two arms again.

Ramachandran found that making a paralyzed phantom limb move could reduce the pain. In 1999, Ramachandran and Eric Altschuler used the mirror technique for stroke patients. It helped improve muscle control in their weakened limbs. The way it helps with movement might be different from how it helps with pain.

Mirror therapy was introduced in the late 1990s. However, not much research was published on it before 2009. Much of the research since then has been debated. A 2018 review looked at 115 studies on mirror therapy for phantom limb pain. It found only 15 studies with strong scientific results. From these studies, the reviewers concluded that mirror therapy seems to help relieve phantom limb pain. It reduces how strong and long the pain episodes are. It is a useful, simple, and cheap treatment. A 2017 review looked at more uses for mirror therapy. It concluded that mirror therapy has been used for phantom limb pain and other conditions. The exact way it works is still unclear. But the evidence that it helps is promising, though not yet definite.

Mirror Neurons and Empathy

Mirror neurons were first found in 1992 by a team led by Giacomo Rizzolatti. These special brain cells fire when a monkey does an action. They also fire when the monkey watches another individual do the same action.

In 2000, Ramachandran made some "speculative guesses." He thought that mirror neurons in humans could be as important for psychology as DNA was for biology. He believed they could help explain many mental abilities that were once mysterious.

Ramachandran has suggested that studying mirror neurons could help explain human abilities. These include empathy (understanding others' feelings), learning by copying, and how language developed. In a 2001 essay, Ramachandran thought that mirror neurons could help us understand others' intentions. He also thought they played a key role in human traits like empathy and learning through imitation.

Some scientists agree with Ramachandran's ideas about mirror neurons and empathy. Others have questioned them.

"Broken Mirrors" Theory of Autism

In 1999, Ramachandran and his colleagues suggested a theory. They thought that problems with mirror neuron activity might cause some symptoms of autism spectrum disorders. Between 2000 and 2006, Ramachandran and his team published articles supporting this idea. It became known as the "Broken Mirrors" theory of autism. They did not directly measure mirror neuron activity. Instead, they showed that children with autism had unusual brain responses (called Mu wave suppression) when they watched other people's actions. In his 2010 book, The Tell-Tale Brain, Ramachandran said the evidence for mirror-neuron problems in autism is "compelling but not conclusive."

The idea that mirror neurons play a role in autism has been widely discussed and researched.

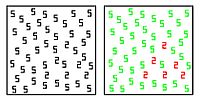

How Synesthesia Works in the Brain

Ramachandran was one of the first scientists to suggest that grapheme-color synesthesia happens because different brain regions are "cross-activated." This means signals from one area accidentally trigger another. For example, seeing a letter (grapheme) might trigger the part of the brain that processes color. Ramachandran and his student, Ed Hubbard, used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in their research. They found more activity in the color recognition areas of the brain in people with synesthesia compared to those without it.

Ramachandran has also guessed that conceptual metaphors (like "a bright idea") might also have a brain basis in this cross-activation. As of 2015, the exact brain basis of synesthesia had not been fully proven.

Sharing Science with Everyone

Ramachandran has written several popular books about brain science. These include Phantoms in the Brain (1998) and The Tell-Tale Brain (2010). Phantoms in the Brain was even made into a 2001 PBS Nova TV special.

In 2003, the BBC chose Ramachandran to give their annual Reith Lectures. These are a series of radio talks. Ramachandran gave five talks on "The Emerging Mind." These talks were later published as a book with the same title.

Ramachandran has also given many other talks, including TED talks in 2007 and 2010.

In 1997, Newsweek magazine listed him as one of 100 "personalities" whose creativity or talent would make a difference. In 2008, Foreign Policy magazine named Ramachandran one of the "World's Top 100 Public Intellectuals." In 2011, Time magazine listed him as one of "the most influential people in the world" on their "Time 100 list." Both the Time and Prospect selections were chosen by public voting.

Awards and Honors

Ramachandran has received many academic and other awards. For example, in 2005, he received the Henry Dale Medal. He was also made an honorary life member of the Royal Institution of Great Britain. He gave a special lecture there, joining famous scientists like Michael Faraday. His other honors include fellowships from All Souls College, Oxford, and Stanford University. He also received the Presidential Lecture Award from the American Academy of Neurology. He has two honorary doctorates, the annual Ramon y Cajal award, and the Ariens Kappers medal.

In 2007, the president of India gave him the Padma Bhushan. This is the third highest civilian award and honor in India.

In 2014, the ARCS Foundation (Achievement Rewards for College Scientists) named Ramachandran its "Scientist of the Year."

Images for kids

See also

- Body image

- Oliver Sacks

- Phantom limb

- Phantom pain

- Synesthesia

- Sound symbolism (phonaesthesia)

- Temporal lobe epilepsy